Soon after I began my research into the lives of the child laborers photographed in Winchendon by Lewis Hine, the late Catherine Joseph Drudi, of Winchendon, recommended that I contact Eric White, a member of the first generation of Whites that did not own the Spring Village Mill. I visited his home in Williamstown, Massachusetts, and showed him all 40 of the pictures.

Coincidentally, he had recently begun making frequent visits to his home town to put together an account of his family history, which had been compiled by his stepmother, Shirley Emerick White. He was working with the Winchendon Historical Society on the project. In addition, he was about to donate a stunning relic to the society’s museum, a large dollhouse replica of the house he grew up in on the property called Captain’s Farm, on Elmwood Road in Winchendon Springs. The dollhouse had been painstakingly created by Shirley, who passed away in 2006 at the age of 90.

The Hine photographs filled an empty spot in the history of the White family. They represented the only known images of people working at the Spring Village Mill and the Glenallan Mill in the 20th century. Eric and I have continued to meet and correspond. He took me on several tours of Winchendon, including the property where Marchmont, the “castle” home of his ancestors, stood until it was demolished in 1955.

On April 22, 2009, I interviewed Eric in what he calls the “guest house,” a separate building next to his house at Captain’s Farm.

Manning: What is your full name, and when were you born?

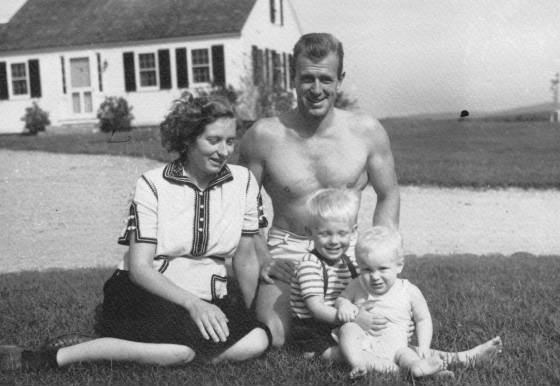

White: Eric Shaw White. I was born December 28, 1940, which isn’t so good, because it’s right after Christmas. My brother Jody, full name Joseph Nelson White IV, had the same problem. He was born on December 26, 1938. My sister Carol was born January 19, 1941; and I also have a younger brother, Fred, who was born April 4, 1945. I was born in Boston Lying-in Hospital. It’s not as if my mother traveled all the way from Winchendon to Boston to have me, but rather because my mother was originally from Wellesley, where we spent quite some time during World War II. Her name was Lucy Howard Lee White. My father, Joseph Nelson White III, was born in Fitchburg.

Manning: Did your father grow up in Marchmont?

White: Yes. His was the last generation to live and grow up in Marchmont. My grandfather, Joseph Nelson White Jr., died in 1939. All his children were grown by then, leaving my grandmother, Rebecca White, living alone in this ‘castle.’ So she left Marchmont soon after her husband’s death and moved to Cambridge, Mass. That is when people stopped living in Marchmont, and the house was shut down. The original settler was Nelson Davis White, my great-great-grandfather, who came to Winchendon in 1847 from West Boylston, MA. He purchased the mill and started the family operation.

Manning: Were your parents living in Captain’s Farm when you were born?

White: Yes. They moved here in 1938.

Manning: When you were growing up, did your father own any mills other than the Spring Village Mill?

White: Not him. But if you go back one or two generations, the White family owned the Spring Village and Glenallan Mills in Winchendon, and the Jaffrey Mills in New Hampshire. The family also had a mill in White Valley, Mass., which was flooded for the Quabbin Reservoir in the 1930s. I remember reading about my Uncle Nelson going down there on the train.

Manning: When you were growing up, was your father very busy with the Spring Village Mill?

White: He was always down at the mill, my mother was up here at the house, and I, quite often, was down in Spring Village playing with all the kids. As a business, the mill did well during World War II, and made it through the Korean War, but things wound down after that. One day, while my father was driving by the mill, he told my brother Jody, ‘When you grow up, this mill isn’t going to be here anymore.’

Manning: Did you ever go into the mill?

White: I went into the mill itself a few times. I remember watching the workers hand-shovel coal into a giant furnace. The entire work area was extremely hot. I also remember that the noise from the machinery inside the mill was incredible. There were supporting beams in the back of the building to keep the mill from shaking too much when the looms were running. Since I was one of the White kids, some of the workers would pat me on the head and say, ‘Hi, how are you?’ Naturally, I received a warm reception.

Manning: Did you visit your father at the mill and watch what he was doing?

White: Yes. He was usually doing paperwork. His office was where the post office is currently located. He had a big safe behind his desk. I don’t know what happened to that safe, but his office desk is here in the house.

Manning: Did he talk much about the mill?

White: I never got involved in talking with him about the mill or the details of the business. I was off in my own world with my friends.

Manning: What was your family’s relationship with the workers and their families?

White: As far as I know, his generation didn’t mingle with the people that lived in Spring Village to the extent that I did. My father would drive me down to school in the morning, leave me off, and I’d usually walk back home after school.

Manning: So the other kids walked to school, but you didn’t.

White: The other kids lived much closer to the school. I was almost two miles away. I don’t think I ever walked to school in the morning.

Manning: Was it different for you? I mean, you rode in the car to school in the morning, and the other kids walked.

White: I never felt there was any social class distinction.

Manning: You told me that you went off to a private school when you were about 13. Why didn’t you go to private school right from the start?

White: I don’t know. I asked my Aunt Elaine that question once. That generation had a private tutor commuting from Orange (Massachusetts) to Winchendon by train. She taught the family children and some other kids in a building owned by the mill. Starting at the middle school grades, they all went away to boarding school. My parents divorced when I was about 16 years old, and my mother moved back to Wellesley. My sister went with her, but I stayed here.

Manning: Did you want to stay because you wanted to be with your father, or because you wanted to be in Winchendon?

White: Mostly I wanted to stay in my own house, and I wanted to be with all my friends: Larry LaRochelle, Buddy Flint and the rest of the gang.

Manning: So when you went off to private school, was that a disappointment? Would you have preferred to finish school in Winchendon?

White: Well, when I started the sixth grade at the private school, I hardly knew the difference between a noun and a verb. I had to repeat the sixth grade to catch up. It was unbelievable what I hadn’t learned in elementary school in Winchendon. They taught the basics, some math, reading and writing, but that’s about all. I had to sort of pull myself up by my bootstraps, with a lot of help from my teachers, but by the time I finished middle school, I was doing very well academically.

Manning: Did you see yourself as not living in Winchendon anymore when you grew up? Did you want to go out into the world and do something big?

White: Not really. But I knew the mill was going out of business. My brothers and my sister and I became the first generation in the family to have to earn a living doing something different. And we did. It wasn’t until my junior year in college that I decided I wanted to go into medicine. No one in my family had ever done that before; most had pursued business professions.

Manning: What is your specialty in the medical field?

White: Orthopedic surgery.

Manning: Where have you practiced?

White: In Williamstown, from 1972 to until 2006, when I retired.

Manning: Where did you go to medical school?

White: I toured the Ivy League. I was a Yale undergraduate, a Dartmouth medical student during the two basic science years, and then I went on to Harvard Medical School for my two clinical years.

Manning: When did you get married?

White: In 1969, to Linda, during my residency training in New York City.

Manning: How many children did you have?

White: Three, two daughters and a son, Sarah, Emily and David.

Manning: Was it a big disappointment to your father to have to sell the mill to Ray Plastics?

White: I don’t know. I never discussed that with him. It probably was a disappointment, but mitigated because he saw it coming over an extended period of time.

Manning: What did he do after that?

White: It took him quite a while to wind down the mill sale and to manage all the White family property in Spring Village and near Lake Monomonac, which, by the way, is the headwater of the Millers River, which eventually travels west to the Connecticut River. He had a fairly early retirement.

Manning: When did your father die?

White: My father died in 1986. He had remarried in 1959, to Shirley Emerick, my stepmother. He met her on the ski slopes in Vermont. When Shirley died in 2006, I became the executor of the family estate. Up to that point, I would come to Winchendon two or three times a year. When my children were young, I would leave them here with their grandparents at Captain’s Farm. They had a great time. But during those years, I didn’t really interact with the people in Winchendon, because I was too busy establishing a career over in Williamstown. There were a couple of road races here in the 1980s that I ran annually. I would see a couple of my elementary school friends periodically, but I pretty much lost touch with them after the 1960s.

Manning: You told me at lunch about five months ago that if you weren’t working with the Winchendon Historical Society on the doll house and your family history, you probably wouldn’t be coming back to Winchendon like you are now.

White: That’s probably correct. Shirley was a real inspiration. She had been working on the family history since my father died. She would say to me, ‘You’ve got to learn more about your family.’

Manning: But she was not a White, she was sort an outsider.

White: Right. She came from a blue-collar family in Rochester, New York. Nevertheless, she kept after me to learn about my family history. During the 1980s and 1990s, she arranged three well-attended White family reunions. She died at the age of 90. She went from being in very good health to dying in three months, of leukemia. Since her mother had died at age 104 years, I always assumed that she had plenty of time to work on the family stuff; fortunately she did get most of that work done, including the dollhouse.

Manning: How many times have you come to Winchendon since Shirley died?

White: Probably about 60 to 70 times.

Manning: What’s different about coming back now as opposed to coming back before?

White: Well, it doesn’t look the same. As my family’s business along with other manufacturing enterprises went out of business during the 1950s and 1960s, I watched downtown Winchendon slowly disintegrate. One hundred and fifty years ago, Winchendon had been one of the centers of New England’s Industrial Revolution. As manufacturers in town were going out of business, the retail establishments on Central Street dwindled. When they put in the Route 202 bypass around Gardner that connected to the east-west Route 2 corridor, Winchendon became a bedroom community. The kiss of death was Wal-Mart in Rindge, New Hampshire, which is only about four miles from the center of town. I remember as a kid in the 1940s going down to watch the trains come into the station. Originally, trains left Winchendon in five different directions. In the 1950s, I watched them build the Clark Memorial (YMCA facility). As teenagers, we used to go there a lot. That’s how I got to know a few of the ‘downtown’ kids from Winchendon rather than Spring Village. Now, Winchendon is pretty much a ghost town from a retail or manufacturing viewpoint.

Manning: Was there a big difference between the downtown kids and the Spring Village kids?

White: Oh, yes. The downtown kids were the tough guys. They weren’t in our clique of people.

Manning: If you showed up in the downtown, would the kids say things such as, ‘What are you doing down here?’

White: I don’t remember specifically, but that was the sense you’d get. Of course, the kids from both sections went to Murdock High School downtown and blended together. By then, I was out of the picture, living out of town in boarding school.

Manning: It seems to me that you have suddenly been thrust into reconnecting with the community. You’ve talked to me a lot about all these friends you’ve been seeing a lot of lately. I get the sense that you are more engaged in the town than you expected you would be.

White: Yes, I have been. I’ve come to grips with the fact that the heart of our town is now the big parking lot by Dunkin’ Donuts. Now I just shake my head when I think about the demolition of that section of town. But I’ve gotten used to it.

Manning: A couple of times, you’ve emailed me and told me about some good places to hang out. How did you find them so quickly? You told me about Dunkin’ Donuts and the American Legion.

White: I found them just like you did. I just went to Dunkin’ Donuts because there are not many other places in town to go to. I showed up in town early one morning, and I saw all the school busses parked there. I knew that the locals converged there regularly, so I went in. During one of my trips, I drove by Nik Rylee’s. That spot used to be Casa Giardini Restaurant, and then some sort of pizza place. It’s a good restaurant now. I go there frequently.

Manning: You walked into Dunkin’ Donuts one day when I was in there, and everybody recognized you right away. One guy said, ‘Aren’t you Eric White?’

White: Maybe some of the older generation recognized me. I’ve presented issues at the selectmen’s meetings two or three times. They broadcast the meetings on the local television network, so maybe a few of the older residents recognized me.

Manning: I started doing my research on the child labor photos just a little while after you started working on your family history. That was sort of serendipitous. How did you react to the pictures of the children working at the White mills?

White: It made me think of that photograph taken in 1867 of the Spring Village Mill workers standing outside the building along the fence. When Shirley showed me that photo several years ago, I started wondering about the relationship my family had with the mill workers. Then you came along and dropped the Lewis Hine child labor bomb on me. I’ve read a lot of my family documents that Shirley had organized. They wrote most of it, so naturally you get their point of view. Nevertheless, I think that my family truly cared about the people who worked for them. I believe they took care of them as best they could. My family hung in as long as they could when a lot of other textile mills in New England were going out of business.

Manning: According to much of what I have read about the history of the mills in Winchendon, most of the children who were photographed by Hine, and their parents, had been living in Winchendon 10 or 15 years by that time. Almost all of them were French Canadians who would have come from poor living conditions in Quebec where they were farmers who grew root vegetables and other crops that could survive a cold climate. They were happy to come down here and have a house with a low rent, get steady work, and bring their kids up in the mill culture.

Of course, families with lots of children were ideal for the mill owners, because it was a way to recruit more workers as they grew up. But at a certain point, probably the next generation, there would have been a growing attitude that toiling at the mill wasn’t going to get them anywhere in life, that there were better jobs elsewhere, that graduating from high school and going to college created better opportunities, and that the wages and working conditions weren’t fair. And they would have heard about unions in other localities.

White: I was whisked away to boarding school around that time, so I was unaware of those kinds of feelings. Somewhere in the late forties and early fifties, I think the mill was unionized, just before it went under, due to the industrialization of the south.

Manning: The GI Bill made a big difference. Kids could come back from the war and say, ‘I don’t have to work in the mill anymore, I can go to college and get training and do something different, and I can buy a house.’ That would have been happening all over the US, not just in Winchendon. Many of the children Hine photographed were under 14 years old, at least the ones he pointed out. Some were older than he thought, but he was correct about the ages of most of them, according to my research. The Massachusetts law prohibited mill work for children under 14, so many of the children he photographed were working illegally. At that time, there was little enforcement of the law, and that’s why Hine took the pictures. Some of the younger children he photographed might have been just helping out or working only a few hours a few days a week. Does knowing this have an impact on you?

White: It’s certainly fascinating. While associating with the children of the mill workers during the 1940s and 1950s, I never sensed that their parents were exploited, but, of course, I was young and I was a White. The mill workers feelings weren’t necessarily imparted to their children.

Manning: You have the 1867 photo of the Spring Village Mill workers you mentioned, several photos of the adult workers inside the mill in the late 1800s, and now the Hine photos. Do you have any other photos of the workers from that time period?

White: I have a bunch of pictures of the family at Marchmont, but very few of mill activity.

Manning: It’s interesting that the Winchendon Historical Society wasn’t aware of the Hine photos until I showed the pictures to them.

White: Well, we weren’t the only business in town. And we were in Spring Village, not in downtown Winchendon.

Manning: In terms of manufacturing in Winchendon, your family was making mostly denim, not beautiful wooden boxes or popular toys. It’s called Toy Town, not Denim Town. Your family’s business wasn’t all that big.

White: You’re right. When I went through the Winchendon Historical Society Museum, I saw a lot of stuff down there about the Whitney family (wood products manufacturers) and the Converse family (toy manufacturers), but there was very little about my family. That’s why I’m working now on putting together some information for them. They were very pleased to get the dollhouse. They found the perfect place to display it. When Shirley was alive, she talked about sending it to Worcester, and I said, ‘What about the Winchendon Historical Society?’ But she was worried about that. She said, ‘They’ll just put it down in the basement, and nobody will come and look at it.’

Manning: Do you see an end to your coming to Winchendon?

White: Perhaps sometime, but I don’t know when it’s going to happen. The biggest issue that brings me back here is this property and Captain’s Farm. I’m dealing with 625 acres of undeveloped land that my father wanted us to keep forested. So I am trying to come up with a plan. Because I grew up in it, I’m very attached emotionally to this house. We looked at renovating it for a single-family dwelling, but the cost of that was prohibitive. This complex would need at least a half-million dollars of renovations. If we sold it today, ‘as is,’ it would be bulldozed and the new owner would build a trophy home here. I don’t want that, so I’m waiting for the phone to ring. I need somebody with a good idea as to what to do with it. This would make a great headquarters for a non-profit enterprise. The Trustees of Reservations came out and looked at it, but they said that none of the non-profit organizations want to deal with old buildings, because of maintenance costs. If I can find a way to preserve the house and the property, that might be the end of my work here.

Manning: You took me down some street a couple of months ago where there are some houses at the bottom of a hill, and we could look up straight up the hill at your house. When you were a kid, did you ever look up at your house from there and say, ‘Wow, that’s my house. I’m pretty lucky.’

White: Sorry to disappoint you, but no. When I was a kid running around on our stone wall, many of those houses at the bottom of the hill were not there. When you are young, one often doesn’t appreciate the obvious.

Manning: But you must have walked down to the bottom of that hill many times. Didn’t you ever look back and admire your house?

White: Sure, I did.

Manning: What was the greatest thing about growing up in Winchendon? What made you the happiest?

White: Being a free spirit with my friends down at the elementary school. I didn’t have a lot of toys, although I’m sure I had more toys than a lot of the other kids. This building we’re in now used to be a barn. They made it into a guest house, but basically it was a way for our parents to get the four kids out of the house. Because the design of Captain’s Farm was pre-1940, there were no family rooms, and it’s quite small in terms of square footage. But we didn’t spend a lot of time hanging around in the house anyway. We were always outdoors, even in the winter. We would take our notorious sled rides down Elmwood Road. This may be folklore, but I think it’s really true. You could get on a sled and go almost one mile down to Spring Village without stopping or having to walk. We counted four separate hills. The first and biggest near the house is steep and the longest. Its descent would give you enough momentum to get you across the flat. Maybe we had to push a little bit, but not too much; then we’d head on down the next three hills on a roller coaster ride to Spring Village. In the winter, the town would occasionally close Elmwood Road to cars to protect the sledders.

Manning: Was there someplace you would go to where, if your parents were looking for you, they would know that you were probably there?

White: I never had a sense that anyone was looking after me or wondering where I was. Larry LaRochelle and Buddy Flint were my best friends. We might be playing in the woods or down at the frog pond shooting our BB guns. No doubt, my mother knew where I was, or if she didn’t know, she would call Larry’s mother or Buddy’s mother, and one of them would know. It was a small community, with a population of about 700 people. There were no ‘helicopter’ parents back in those days. The telephone operator probably knew where we were.