“My Uncle John wanted to start a restaurant, a diner as it happened to be, so they ordered the diner from a company, and it was delivered here. It had sliding doors and marble counter tops. It was a good diner. It sat long ways on Ashland Street, and there was an entrance from there. There was like an alleyway where they parked cars, and there was an entrance from there, too.”

“It was long like a train car. It was all counters and seated about 50 or 60. The grill was right out front. You’d order a hamburg or a steak, and it was cooked right there on the grill. It was open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, right up until the 1940s. It opened in the early ‘20s down near where the Richmond Hotel was. Then they moved it up on Ashland Street after a few years.”

“They made a custard pie that was very famous. They made a strawberry pie, and people used to come from everywhere for it, or for the banana cream. They had a blue plate special. Certain days of the week, they’d have spaghetti and meatballs or a pot of beef and spaghetti, or corned beef and cabbage. People knew what the special was, and they knew that on a certain day, they could always get it.”

“At lunchtime, they used to come up from Sprague’s on Marshall Street. Back then, Sprague’s had thousands of people. They’d feed so many people in that diner in such a short period of time. It was amazing. A guy would walk in the door, yell out what he wanted, and by the time he found a seat, the plate was there. My Uncle John had a cigar box where they’d cash up. You’d tell him what you had, and the cigar box came out even every day. Then they got a cash register, and that never came out right. I remember my Uncle John saying, ‘Boy, I have to go back to the cigar box.’”

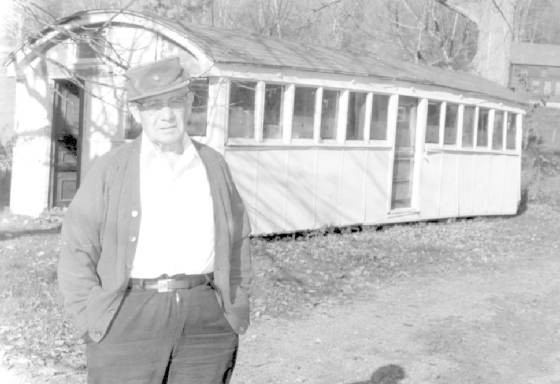

“Uncle John finally moved to a farm in Cheshire called Rolling Acres Farms. Then the Post Office expanded and took all the property the diner was on by eminent domain. So Uncle John closed the diner and took it to Cheshire. He had it down there in his back yard. It wasn’t doing anything. A lot of people would stop by and just want to visit the diner. He kept it clean, but it was all rotting apart.

“The diner was finally torn down. Uncle John died, and I handled the estate. I was going to have to get it moved, and it was cheaper just to dispose of it. Because of all the marble in it, the guy that did the demolition didn’t charge me anything to take it.” -Paul Dilego, Sr.

I remember my first diner. It was on Route 301 in La Plata, Maryland. I was 19 years old and living in a room in a private home while attending a small community college that had classes only in the evening. I went down there one night to cram for a biology exam and wound up doing an all-nighter. I sat in a booth in the corner and kept myself going on donuts and coffee till sunrise. A few truckers came in, and the waitresses chewed gum and gossiped at the end of the counter. I felt comfortable, and everyone was friendly. I went there a lot after that. That was in 1961. The diner isn’t there anymore. The highway has changed so much, I can’t even figure out where the diner stood. By the way, I got an “A” on the exam.

In 1965, I drove by myself all the way from Annapolis, Maryland, to the Colorado Springs, where I was stationed in the Air Force. I took Route 50 nearly all the way. Near Sandoval, Illinois, I stopped for lunch at a roadside diner called the Starlite on a miserable rainy day. I ordered a hot roast beef with mashed. I got a long plate with the sandwich in the middle and two scoops of potatoes, one on each end. It was good.

Six years later, my wife and I were headed back to Connecticut from Colorado on Route 50 after a long vacation. When we crossed the Mississippi on the East Saint Louis Bridge, I remembered the Starlite. “It’s somewhere near here,” I told her. We were hungry. Suddenly, there it was. We ordered the hot roast beef with mashed. Nothing had changed. Two scoops of potatoes, one at each end of the plate. Still good, too.

People don’t go to diners and small-town cafés like they used to. For one thing, most white-collar workers take half-hour lunches now. They can either work more hours that way, or get home earlier. So it’s a quick trip to the drive-thru. You bark your order to a speaker, pull out some bills, count your change, lay the bag on the passenger seat, and drop the drink in the cup holder. Then you gobble it down while the radio blasts out some rude talk show.

It seems like we can go through almost a whole day now without seeing or talking to anyone. Breakfast is eaten either in front of the TV, or it’s wolfed down alone in the car on the way to work. Many of us eat our lunch at our desks (gotta keep working), or it’s back to the drive-thru again.

Stop for gas, and you swipe the credit card through the slot. No “Fill ‘er up” anymore. They even have drive-thru drugstores now. In Waterbury, Connecticut, they have a funeral home where you can drive through and view the body. I’m not kidding.

You can order over the Internet or from an 800 number with a credit card, so why go to the store? Why go to a live music concert when there’s one on Pay-Per-View tonight? Or rent a video and see it in the privacy of your home.

Diners and small-town cafes give us good food at low prices. More importantly, they give us a chance to talk with folks we’ve probably known for years but haven’t seen lately, or to meet someone we might enjoy getting to know. Most have been swept away by urban renewal, the interstate highway system, and fast food joints. The ones that have survived are haunting reminders of a slower and more rewarding lifestyle.