A few months ago, I was taking some photographs of the building facades along the downtown block of Eagle Street, when one of the storekeepers came out and asked me what I was doing. When I told him, he said:

“There’s nothing here worth looking at. In fact, there’s nothing in North Adams that I would want to take a picture of, except perhaps the view of the city from the Hairpin Turn. I guess that’s not bad. But when you get down here in the valley, there’s nothing, just nothing.”

Perhaps this storekeeper doesn’t believe in miracles; miracles like that Hairpin Turn he mentioned. Anyone who understands that there is a God must be in awe of Him for creating this incredible view of North Adams, a view created over a span of millions of years by a combination of geographical phenomena such as glaciers, rivers and storms.

When I come over Burlingame Hill (Stewart White Road) in Cheshire and pass the Gulf Farm on my way to North Adams, I see a different sky and a different blend of colors every time. Sometimes there are huge pockets of fog in the valley that look like overstuffed pillows. In the winter, the barn-red buildings, sitting in satin blankets of snow, glow in the early morning against a baby blue sky. Last month, saturated by spring rains, the richly textured green farmland reminded me of Ireland. There hasn’t been a day I have crossed this “cow path” without being tempted to screech to a halt and jump out with camera in hand. When I wonder at these marvels of nature, I am really thanking and praising God for miracles. After all, He created them for us to enjoy.

God also creates miracles through the people we meet. Tony Talarico is an example. I am among the many hundreds, perhaps thousands of people he touched in his nearly 87 years.

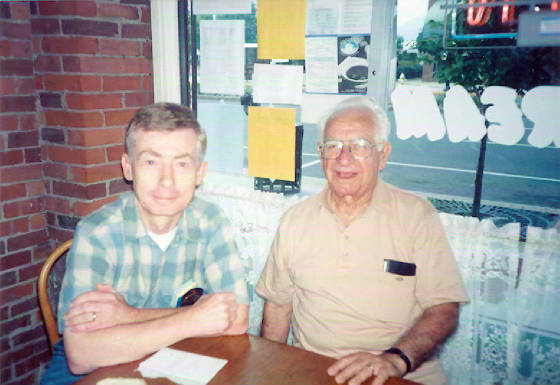

When I interviewed Tony Sacco in October of 1996, for Steeples, he brought along Tony T. as a guest. They talked for nearly three hours at a booth in McDonald’s, while I sat with my tape recorder and a list of questions I never had to consult.

No more than a few days after the interview, Tony T. mailed me a large envelope containing carefully written information about his life. It was full of the sorts of details that most people forget or never get asked about. I wrote and thanked him, after which he sent me more.

A few months later, I was sitting at the counter by the front window at the Bean one early morning, and Tony walked in. I hadn’t seen him since the interview, but I recognized him at once. He saw me and came over. He said: “You’re Joe Manning, aren’t you? I like you. You know how to listen. I’m sitting with some friends over at the big table. Come over and join us.”

Thus began a deep friendship that changed my life immeasurably. From that day on, nearly every visit to North Adams began with our morning talks at the Bean. He brought me gifts, like an old brick from the Hoosac Tunnel and a granite block salvaged from the demolished Berkshire Apartments on Bank Street. Soon the routine became almost a ritual.

I would arrive around 7:00 a.m. and watch at the window for him to drive up in his red car, which he parked across the street in front of Radio Shack. He would get out, wave, and walk down happily to the Holiday Inn to work out on the weight machines. At about 7:45, he would come back, get something out of the car for me, and cross Main Street. I would step out and wait for him at the curb, and he would give me a hug.

Tony was always eager to tell me his wonderful stories and reminiscences of growing up in North Adams, but he often talked about the present and the future, too. He was never stuck in the past. He had a computer and was on the Internet long before I even thought about it. He even had a website that included still more stories, some of which he printed out for me when each one was finished.

Tony taught me about the simple gifts that are the miracles of our everyday lives. By example, he helped me recognize that my love for the humble beauty of North Adams and its people is founded on the principle that all things and all people are blessed with God’s presence, and each one is a miracle to be discovered and cherished. That is the legacy he left me when he passed away in his sleep on the first full day of this summer.

Ten days later, my wife and I attended the outdoor silent movie event at Mass MoCA. Live music by the Alloy Orchestra accompanied hilarious short films by Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and Laurel and Hardy. It reminded me of watching Metropolis with Tony and his daughter Jean at Mass MoCA last summer, also with the Alloy Orchestra. The artful, German Expressionist silent film, and the thunderous, rocking, percussive score was an overwhelming audio and visual experience. After the show, Tony was so thrilled, he could hardly contain himself: “Wasn’t that just great! The music was so exciting. I loved it.”

Tony was 15 years short of a century then, but he was still a young man. His love of life and his generous spirit will follow me wherever I go.

“Those who love deeply never grow old; they may die of old age, but they die young.” -Sir Arthur Wing Pinero, English dramatist (1855-1934)

As a special tribute to Tony, here are some of his memorable stories and comments I have collected from our visits at the Bean:

“I used to go camping with my family in Charlemont every summer. When I came home from work every day, my wife Helen would be cooking dinner. I would always honk twice when I was getting close.”

“The North Adams Transcript is missing out by not putting names of people in the paper. When Jim Cleary and I were on the Hoosac Tunnel Centennial Committee, we used to spend an hour and a half writing up the meeting for the Transcript. Next day, everyone on the committee would get the paper so they could find out what they said.”

“My brother and I were driving down to New York City to pick up a friend. About an hour before we got there, this guy on a radio show starts talking about pigeons. When we got there, he was still talking about them. We picked up the friend and got something to eat, then started back. When we turned the radio on, that guy was still talking about pigeons.”

“Henry Koloc’s father had all kinds of trained pigeons. I drove to Albany and back with Henry once, and he talked for two hours about those pigeons.”

“The worst fight I ever saw was between two pigeons. One of them had his eye hanging out. There was a female pigeon watching, and she chose the winner.”

“Twice a year for I don’t know how many years — I’d have to look it up — I set up a luncheon reunion for my Drury High School classmates. It always seemed as if we got a pretty good turnout. There weren’t that many that had died. The minute we bragged about that, a bunch of them died. Now we have the reunion for five classes, from ’31 to ’35. We couldn’t find anybody from ’32, but I just heard about somebody. But I forgot who it is.”

“A few years ago, I went down to North Carolina twice with one of my neighbors. I made a lot of friends down there. I’d go to the waffle house and sit at the counter, and there would be a group meeting every day at ten o’clock in the morning. I love grits. I went to the waffle house on Monday and ordered grits with a poached egg on it. The poached egg wasn’t that great. By Friday, the cook was doing it just right. I went in there Saturday, and the place was jammed. The waitress says, ‘Do you want a poached egg on grits?’ And I says, ‘No. I want tomato sauce on the grits.’ She couldn’t get the courage to tell the cook. I finally got it, and I says, ‘Got any grated cheese?’ And she says, ‘What’s that?’ Sunday, I go in there, and she says, ‘Go back home.’”

“I go to Tai Chi every week. I don’t know where I’m goin’, and I don’t know what I’m doin’. All I know is that now I can put on my pants standing, but I still have to sit down to put on my shorts.”

“I started the Talarico Special up at the Readsboro Inn. I wanted oatmeal, so they gave me oatmeal with raisins and a little brown sugar. Next time I went up there, I says, ‘How about apples, too?’ Another time, I told them to put in blueberries; then bananas. So that became the Talarico Special. Then I got them to do it at the Miss Adams Diner. They keep the recipe on the refrigerator door.”

“I just won a CD Walkman in a contest. I brought it home and stayed up until midnight trying to get the thing to work. No matter what I did, I couldn’t hear anything. I finally went to bed, and then I woke up later and figured out that you have to listen to the headphones.”

“I think I’ve had my computer about six years. The Internet wasn’t quite that hot then. My daughter got a new computer and gave me her old one. I learned everything by trial and error. I heard about websites, so I started my own. I started writing about my father and mother coming from Italy. And then I started writing about when I was four or five years old and I was growing up on Holden Street. There’s quite a few people who told me they liked what I wrote.”

“Lately, I haven’t written as much on my website, because I’ve been writing these little stories for NorthAdams.com. How that started was that I volunteer at the information booth, and it was boring if nobody came in. So I’d go into the Windsor Mill and look around and see what was there, and I became friendly with Ozzie Alvarez, who has a company there and started NorthAdams.com. It happened that I went there once, and he had this birthday cake for one of his employees; so I ended up with a little piece of cake. Another time I went in, they had another birthday party. Then Ozzie began telling me when he was going to have another birthday party. Pretty soon, people were asking me, ‘How did you know we were having a cake today?’”

“Times were tough during the Great Depression. I had a friend who told me once, ‘Every time I’m down to my last nickel, I buy a cigar.’”

“In the afternoon, what I’ve been doing for five years is to take a friend or neighbor to the Blue Benn Diner in Bennington, Vermont. Each time, I take a different person. I go up two or three times a week. If you go up at lunchtime, you have to wait for a booth. I leave at two o’clock, and it’s two-thirty by the time we get up there, and it’s thinned out, so you can get a booth. Personally, I’d rather sit up at the counter, if there are people there, so I can talk to them. We’d go to a place and sit up at the counter so I could talk to people. When I traveled, I found that wherever I went, people who are on vacation are with their husband or wife day and night, so they like to have a chance to talk to somebody else. So I would give them the opportunity. I’ve been going up to the Blue Benn with my sister-in-law Catherine. We go up Sundays about eleven-thirty, and that place is jammed. She always tries to get a seat at the counter for me where there’s a good-looking girl next to me. This Sunday, I talked to this guy on my right. In the meantime, Catherine turns around to the man on my left and says, ‘You know, I don’t usually talk to strangers, but he’s always talking to somebody else.’”

“I remember my mother singing Italian songs as she worked around the kitchen. She was a great cook. She baked her bread in the oven of a black coal stove. She also knitted, crocheted, and spun thread. She must have been some kind of a healer. Neighbors would come in with a sick child, and Ma would pray over them. Then the child would run out and play as if nothing was wrong.”

“I worked at the Arnold Print Works while my brother Gene went to Bryant College. I made $14 a week. I was a laborer doing basically a woman’s job, and I was working nights. That plant was running 24 hours a day, six days a week, during the Depression. Then I went to Bryant, and Gene worked and paid my board. When I came back from college, I tried to get a job in New York. I was down there a week, and I kept putting in applications all over. One guy finally told me that no one was hiring Italians, so I came back home. Then my brother found me a job across the street from Arnold, and instead of making $14 a week and working only five days a week, I got $15 a week and worked six days a week, and I had to dress up in a suit.”

“When we had the flood in 1927, my father had his tailor shop on Holden Street right near Main Street. My cousin was working over at the Arnold Print Works and came over about five o’clock in the afternoon. I was at the tailor shop, and my mother was there, too. My uncle couldn’t cross the Marshall Street bridge because the water was going over it. He told my father that we’d better go home. So we got in my father’s car, came up Center Street, and when we got on Eagle Street, the water was up above the hubcaps. We crossed Union Street, and a big log came down and just missed the car. River Street was like a regular river. We lived on Harris Street, which is off River Street. At the foot of Harris Street, there was a store. The water was so strong that it took that store and turned it around and floated it down the river. There were about three tenement blocks right after Harris Street. The water began to eat away at the first tenement block. All the people in the houses put planks from one tenement block to the other and crossed over to the center of the middle tenement. The fire department came over and put a ladder across River Street, which was like a rushing torrent. People were screaming. I can still hear it.”

“My father was in many plays that St. Anthony parishioners put on. I remember him studying his lines by candlelight. He would get half-burned candles from a barrel in the basement of the church. Once we were in a play together, and I played the part of Columbus’s nephew. I must have been about five or six years old. In one scene, after a long, trying day, they stopped at a tavern, where they served me a meal of a few slices of pepperoni and a few pieces of dry bread. I ate it with such relish that the audience went hysterical with laughter. I never was in another play.”

“Helen and I got married on February 14, 1946. Then I got a job in Washington, DC, working for the Civil Service Commission in temporary buildings on the mall, where the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum is today. I went down first, and Helen came down a little later. I had to find an apartment, and we ended up living in a project for veterans. Before she came down, I painted the whole place. I bought two forks, two knives, two spoons and two pillows. I don’t remember whether I bought two sheets. We had one little room. For a bed, it was just two pieces of a little bed on the floor. Every night, we had to put it down; and every morning, we had to pick it up. We had an icebox, a little table and two chairs, a little gas stove, a sink, a toilet, and a shower. That’s all there was.”

“I regret not hugging my father when I was a kid. He was a loving man. We wanted to be tough like Americans. Now, I need at least three hugs a day.”

|

|

|

|