|

|

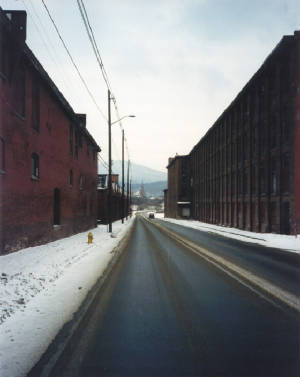

When you drive down the Mohawk Trail into North Adams and come around the turn past the entrance to Beaver Street, it pops up suddenly – that forever startling scene – the two long brick mills, the narrow passage between, and Notre Dame church in the distance. Just across the river from the mills, a row of old houses line up along Front Street.

This picture is not beautiful, but if you have a historian’s appreciation for the stories it tells, or an artist’s affection for the muted colors and gritty textures of industrial America, it is pleasing to the eye. Unless we sweep it all away in another wave of modernization similar to that of the post-war era, North Adams will remain an outdoor gallery that portrays the struggles of our ancestors and the rugged environment in which they carved out their lives.

That’s one of the lessons learned in Nancy Kelly’s quietly emotional movie Downside UP. Contemporary art at Sprague’s, a wine-filled romantic night spent in a converted mill house on River Street, and expensive hand-made gifts from Africa in Eagle Street windows cannot obscure the working-class roots that lie underneath the Hoosac Valley. North Adams may never possess the carefully cultivated gentility of Williamstown, or the chic-and-boutique flavor of Northampton, but its landscapes will remain a testament to a simple life largely unadorned by any pretense of fashion or privilege. And that is something in which to take pride.

I thought about that as I walked on Front Street on a warm, but bleak February day. The well-worn houses facing the dark side of the mill reminded me of a complaint I overheard about Downside Up. “Why did they have to show all those rundown mills and tenements?”

Front Street starts at Cliff Street and runs into a dead end where the land slopes up steeply above the dam. All but one of the houses are on the north side. With their backyards facing a big hill, it looks as if the houses slid down and landed there.

After passing between several tenements on the corner of Cliff Street, I am dwarfed by a huge three-story block with hanging porches. Farther on, I spot a pretty Victorian house whose curving front porch awaits anyone willing to climb the 20 steps below it. A postal carrier pulled up in front of the house while I was taking pictures. “Time out,” he shouted to me, as he took the stairs two at a time, while holding a stack of mail loosely fastened by a rubber band.

A man pulled up in front of another house about halfway down just as I got there. He pointed to my camera and asked why I was taking pictures, and we got into a friendly conversation. I was curious to know how he felt about having the back of the mill staring at him every day. “It’s not so bad,” he replied, “especially since they replaced all the windows. If they tore it down, I’d just be looking at the other mill across the street from it.”

He told me he likes living on Front Street. “I’ve been here about ten years now. It’s a nice dead-end road. When I was a kid, I used to go blueberry picking up on the hill (above the dam). A lot of the neighbors are fixing up their houses. When I moved in, I got an equity loan to repair a big drainage problem in my backyard. As soon as I get that paid off, I’m gonna get another loan and paint the house. It really needs it. Things take time. You do it little by little, just like that mill. They’ll get it done eventually. Look at what Mass MoCA did. Lots of good things are happening here, but they don’t happen overnight.”

When I got to the end of the street, I climbed down an embankment, crossed a little runoff stream, and struggled up the big hill above the dam. I peered down at the river winding toward town and wondered what kind of people lived on Front Street in the pre-flood-control days. Then I retraced my steps and walked down to the library to look up the 1916 listings in the city directory (prior to that year, there was no alphabetical list of streets, so it’s not easy to locate the names of residents of a particular street).

I discovered that a large majority of the residents had French-Canadian surnames and worked across the river at the Hoosac Cotton Mill. I printed a copy of the page and walked back to Front Street. All the present houses and addresses are identical to 1916, except for one house (#64) on the south side that is now a small parking lot. It was kind of eerie to stand in front of each house and look at the name of the family that lived there 85 years ago. What was it like then?

I got permission to explore the upper floors of the Hoosac Mill, now called the Venture Center, so I could get the same view of the houses and the street that the spinners and the loom fixers got a long time ago. I took some pictures through the nice new windows, while I stood precariously on the buckled wooden floor.

Front Street used to be just like River Street, but not anymore. None of the houses have been renovated into a fancy inn. When the mill is restored, it will not exhibit cutting-edge European sculptures, or be host to modern dance performances. Like the nearby Windsor Mill, it will be a collection of spaces in which enterprising young men and women can start a business.

Like the man I met on Front Street said, North Adams is coming along nicely, little by little. By the time he gets around to painting his house, there will another homeowner who has restored an old Victorian on Hall Street, or repaired a sagging porch on Wesleyan Street, or planted a few nice trees in his yard.

By the time the Venture Center is completed, perhaps kids will be playing in the new park on River Street, the new library addition will be going up, the SteepleCats will win the NECBL championship before a sellout crowd, and the Mohawk Theater will be announcing its first performance.

Nancy Kelly is right. Our Downside is UP. But like the upside-down trees to which the title alludes, they are still growing, and they still have to lose their leaves from time to time. Perhaps we should install road signs at every well-traveled entrance to the city that say: “Welcome to North Adams, a work in progress.”

Update: Downside UP was later shown on PBS.