|

|

“Why is it that the kids don’t seem to notice these buildings (at Mass MoCA) at all? I talk to kids who ride their bikes up here. I ask them, ‘What do you think of these old mill buildings?’ There’s no differentiation in their minds between them and the 1950s church across the street. Sometimes I challenge them and say, ‘When do you think this building was built?’ They are absolutely clueless. In this town, there are seven or eight great mill buildings scattered around. You think they would fill a big part of a kid’s imagination.” -Joe Thompson, director of Mass MoCA

Ever since the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art opened in 1999, the following scenario has played over and over in my mind:

It’s 25 or 30 years from now. A major magazine or newspaper interviews an internationally known sculptor, or filmmaker or dancer. The proverbial question pops up somewhere in the conversation:

Interviewer: What inspired you to become an artist?

Artist: Well, you see, I grew up in a little city called North Adams. When I was in the second grade, a big museum came to town.

For those who were lucky enough to attend one of the two performances of The Dream Life of Bricks at Mass MoCA in June, just about anything may seem possible now. Martha Bowers, an accomplished choreographer from New York City, conceived, wrote and directed the show, which featured music, modern dance, drama, and a mysterious late-evening stroll through the gritty and grimy grandeur of the museum’s yet-to-be renovated courtyards and buildings. The huge cast included members of the Drury Drama Team, youngsters from the Greylock Theatre Project, a choir of local singers, dancers from Jacob’s Pillow and Williams College, and even Sprague Electric Company retirees (nicknamed the Sprague Ladies).

Mass MoCA commissioned the work, partly because performing arts director Jonathan Secor is working hard to find ways to involve the local community with the museum. Bowers is noted for her site-specific productions; that is, placing the actual performances in non-traditional public spaces and casting local people in the shows.

In preparation for the production, Bowers visited North Adams many times over the past year and interviewed members of the local community, mostly women who worked at Sprague Electric in its heyday. In an interview a few days after the show, she told me what it was like getting to know them:

“When I first talked to them, I noticed sort of a sadness, sort of a passivity about a number of events in the past. But when I got to know them better, I saw a tremendous amount of strength and humor and wisdom in them. They did whatever it took to get through those times. They’ve had the ability to adapt and change and re-create their identities.”

In The Dream Life of Bricks, the Sprague Ladies certainly demonstrated how to re-create their identities. They wore costumes, danced, and even pretended to sleep in precarious positions at various outdoor locations, as ticket holders took the strange journey to various indoor and outdoor venues.

The title of the show stems from Bowers’ vision that the bricks in the buildings have dreamed various dreams over their 125 years, those dreams now changing once again as they witness art and culture instead of machines and mill workers. And that vision includes the hope that the barriers between workers and company owners, as well as between professional and amateur performers, are breaking down. Bowers elaborates:

“I don’t think of anyone as having more talent than another in my projects. They just have a different role to play. I hope that the audience saw that everyone in the cast, be they 12, or 80, or a professional artist, was an equal in the project. The city is full of talented people.”

One of the segments of the show was a re-enactment of part of an interview I did in 1997 with Krissy Retzlaff and Emily Tremblay, both 11 years old then. The interview was published in Steeples. Here is a brief excerpt:

Emily: I’m gonna be an ice skater like, you know, Scott Hamilton.

Krissy: When I’m 40, I’m gonna be in like every movie there is.

Emily: I also wanna be like a teacher/counselor kinda thing. I could travel all around the world and help people.

Krissy: Oh yeah, that’s my backup job. I’m gonna be a teacher. I need a backup job, ‘cause it’ll take a while to be famous.

Emily: When I’m 70, I’ll be famous, because I’ll be the oldest person to skate. I’ll be the oldest one to put on a show.

Krissy: I’m gonna be the best teacher in the world.

Emily: I also wanna be a lawyer. I’m gonna have my own company called Lawyer-Mart. I’d like to go to Germany and Australia and South Africa. I wanna go to Haiti and help people there, ‘cause they’re like really poor.

Krissy: I’m gonna be living in Hollywood in ten years.

Emily: There’s too many things that I wanna be. I also wanna be a marine biologist. I wanna study whales and dolphins. I wanna be a teacher, lawyer, ice skater, marine biologist. I don’t know. I think that’s it. I sing, too.

Bowers featured the interview to show that young people who are growing up in the shadow of the museum are bound to see almost limitless possibilities for their lives. She continues:

“I think that perhaps what the museum has done is open up new opportunities. And because North Adams is a small town, it’s more likely that local people will have some connection with the artists coming and going, like seeing them in a coffee shop. The Sprague Ladies, when they were teenagers and looked at their future, saw limited options. I don’t think that most of them would have believed they could really become an ice skater or a lawyer or a famous actress.”

Several days before the first performance, I wandered into Courtyard D, where some of the dance parties and concerts take place. A cello player was practicing, and the expressive low tones resonated hauntingly amid the brick buildings. I found out that he was in the show, and that there was a rehearsal about to begin in Building 6. So I went in and watched.

The dark, dusty, empty interior reminded me of those hard-hat tours I attended in the pre-MoCA days. One end of the building narrows to the spot where the two branches of the Hoosic River converge. I saw several old signs that said, “Outside Valve Controls,” as if they were reminding mill workers that the flow of information into the city was controlled from the outside. “Not anymore,” I thought. “Not from the look of things happening in here now. Today, the Sprague Ladies rule.”

I met Leigh Fagin, a 23-year-old museum intern, who was acting as Bowers’ assistant. A native of Long Island, New York, she graduated from Wellesley College with a degree in art history. She was planning to start a new job in New York City shortly after the show, having lived in the museum’s housing on River Street since her internship began in January. A week after returning to New York, she told me that her stint at MoCA was an “incredible” experience.

“I set up rehearsals and meetings with the Sprague Ladies. Martha would throw out questions and have them gab for hours. She asked them to move their hands the way they would have in their jobs at Sprague. Then she would incorporate those movements into the dances by the Jacob’s Pillow dancers. I had never been to North Adams, so I learned a lot by seeing the city through the eyes of these ladies. They were so nice to me. All of a sudden, it was like I had eight new mothers.”

“Martha wanted to get across what it was like to work in those buildings, the feeling of those buildings, the stories those buildings could tell. The show didn’t have much of a structure when she came. It was all about the rehearsal process. I got to see how the Sprague Ladies and the Jacob’s Pillow dancers related to each other, the ladies telling their stories, and then the dancers playing those roles.”

I asked Fagin what she thinks the bricks are dreaming today.

“I think the bricks in Building 6 are kind of jealous of the ones in the finished part of the museum. They’re dreaming of the renovations, when they get to be the walls that the art hangs on, or where the performances are happening. I think they’re dreaming big. It’s an amazing place, and they carry a huge burden, because they hold so much history in them, and they have to represent both the old and the new North Adams.”

Like Bowers, she sees big dreams and exciting opportunities for the younger generation in North Adams.

“I was exposed to art early in my life. That made a big difference for me. All the students in the city go on field trips to the museum. They see new representations of their world. Over time, more kids will become interested in the art and what it means.”

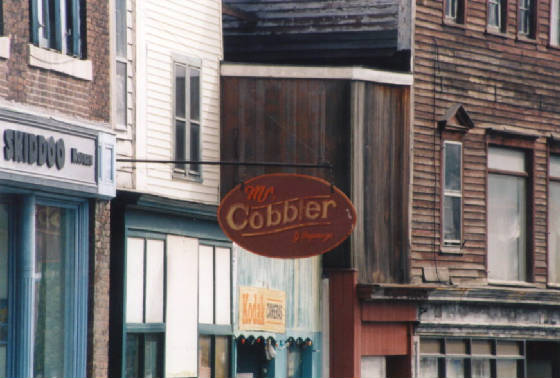

Her comments got me thinking about Cindy Grosso’s fifth grade class at Sullivan School. I helped Mrs. Grosso with a project last spring. I took them on a field trip downtown and led them in a discovery of their hometown. They took photographs and later painted colorful pictures of what they saw. They also visited Mass MoCA. At the end of the school year, each of the students sent me a list of their favorite things about North Adams.

Four years after Joe Thompson worried that the great buildings in North Adams were not filling “a big part of a kid’s imagination,” and three years after Mass MoCA opened, it looks like these bright young people may be dreaming along with the bricks.

“I love Mass MoCA because of the fabulous and interesting art work.” -Sam

“The old buildings fascinate me.” -Cassie

“I like Mass MoCA because of all the contemporary art there.” -Anthony

“I adore all the art on Eagle Street. I just like Eagle Street period because of all the different buildings.” -Kari

“I like having to look up instead of down, because I see things that I’ve never seen before.” -Briana

“I like the architecture.” -Helena

“I like North Adams because we have a terrific place called Mass MoCA.” -Evie

“The Blackinton Block is a sight to see. It is to die for.” -Kyle

“I love the colors of the city. I like the way the buildings are shaped. I want the whole world to see North Adams.” -Ashley

|

|