Every town needs some things to remember, some things to look forward to, and some things that look like success.

Our best friends from Connecticut were visiting one day, and my wife and I took them for a drive. We wound up in Turners Falls, Massachusetts, a 25-minute trip from my home, and one of my favorite towns along the Connecticut River. I pointed out the empty brick factories along the canal, the 1880s architecture downtown, and the Cutlery Block, a long row of mill housing that had recently been renovated into nice apartments. Suddenly, one of the friends asked me, “Why do you always take us to the ugly towns?” I could’ve responded with a cliché like, “They’re not ugly, they have character,” but I just smiled and kept talking.

I prefer to visit and learn about towns with a working-class history, are a bit down on their luck, but possess a quiet potential to renew themselves. They are the underdogs, the ones we like to root for. The small city of Claremont, New Hampshire, is one of those underdogs, and I love the place.

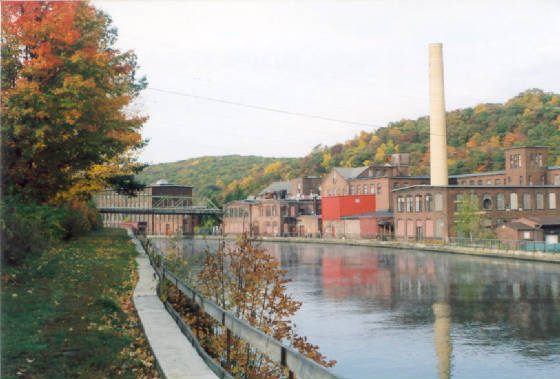

On my first visit in 2003, I stumbled into a conversation with a resident named Marylou, who was tending her tulip garden. She expressed a lot of hope for the city. Since then, she has become a good friend, and one of the reasons I keep returning. Marylou’s hope was not misplaced. Claremont is on its way back. The nearly half-mile of factory buildings along the Sugar River, just north of downtown, are a symbol of its once-prosperous manufacturing economy, but most of them have been vacant for about 40 years. Now a major developer has bought most of them and plans to renovate and retrofit the cavernous spaces for condominiums, apartments, offices and retail stores.

I was in Claremont recently to catch up with Marylou, and I dropped in to see Al Livingston, executive director of Main Street Claremont. His office is on the fourth floor of the impressive Moody Building on Opera House Square. With the measured optimism that is borne of experience, Al talked about the all-too-familiar problem of attracting new businesses and foot traffic downtown. Calling attention to Taste of Claremont, an event planned for mid-June, he expressed mixed feelings. He was excited at the prospect of luring people downtown, but afraid it might just serve to remind them how little there is to see and do.

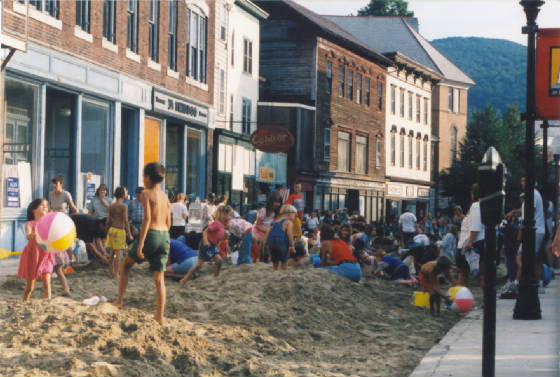

Eight years ago, in North Adams, Massachusetts, artist Eric Rudd talked the city into dumping several dozen tons of sand on tiny, narrow Eagle Street, just off Main, where Mom & Pop businesses have come and gone for 150 years. He brought in a local rock band and invited kids to come and play in the sand for three hours on a July afternoon. Zillions of kids showed up, along with their parents and grandparents.

Eagle Street was struggling then, with plenty of vacant storefronts and buildings starting to slip away from a generation of deferred maintenance. Between picture taking and helping their kids with sand castles, those parents and grandparents couldn’t help taking a good look around, perhaps for the first time in many years.

Like Claremont, North Adams boasted a thriving manufacturing economy, but took a huge hit when its largest factory closed in 1986. In 1999, the complex of 26 abandoned mill buildings became the home of the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (Mass MoCA), spurring a cultural and spiritual revival that has turned the city around, slowly but surely.

Rudd’s Eagle Street Beach is an annual event now, but the street is still struggling, mostly because of landlords who will neither sell their buildings nor invest in them. But there have been some bright spots, and they happened because some creative people looked at the possibilities, got ideas, and followed through on them. All those annual afternoons at the “beach” had a lot to do with that.

After a nice talk with Marylou, I walked around a while and tried to get a sense of what I might notice if I were a curious visitor to Taste of Claremont. The first thing I noticed was the house at 44 Sullivan Street.

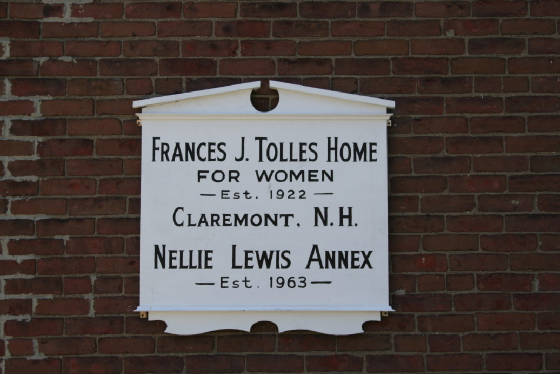

After reading the sign, I said out loud, “Is that all they’re going to tell me?” The sign only made me curious about this apparently important home for women. What was it, and why should I know about it? I could’ve gone to the library and asked, but how many passersby are going to bother to do that? I didn’t.

When I got to the square, I noticed the letters on the corner brick block: FISKE FREE LIBRARY. Some small trees obscured part of it, and it’s likely that many downtown visitors will miss it. I thought to myself: “Well, it’s obviously not a library now; maybe it was an earlier location for the library, perhaps the first.”

The three-story block is a gem. When you look at it from across the square, you can see Mt. Ascutney in the background. What a view! What a place for a restaurant on the top floor, or a small performance space, or a movie theater showing independent films. But I wanted to know: How old is it? What kind of businesses used to be inside? Again, I could’ve gone to the library, but I didn’t have time.

Finally, I noticed that two blocks downtown are getting a makeover. One is called the Dickinson Block. Nice building! Workers were busy inside the first floor. I wondered, “What’s this all about, and what kind of a business is going to locate there? Who was Dickinson? Why did they name a building after him, or her?”

At least it seemed like a harbinger of hope, something to look forward to on my next visit. But why do I have to wonder? If it’s good news, why isn’t there a sign out front that explains it? At least, after residents sample their tastes of Claremont, they can also look forward to their next visit downtown.

The other harbinger of hope appeared to be the Brown Block at the corner of Pleasant Street, historically the city’s central business district. There were lots of workers around, but no sign telling me about the Brown Block (who’s Brown?) and the plans for the building. Given its location and size, it sure seemed like an important project to me. Why was I left with the task of looking it up on the Internet?

When I got home, that’s what I did. I first looked up the Frances J. Tolles Home For Women. All I found was that the home was given to the City of Claremont to be used as a home for “worthy elderly ladies in straightened circumstances, ” and that there was a Frances J. Tolles who was a music teacher at Vermont College in the 1800s. But I don’t know if she was the same one.

Next I looked up the Fiske Free Library, and found some information on the library’s website.

“Samuel P. Fiske established the Fiske Free Library in 1873 with 2,000 volumes from his personal library and $5,000 for the purchase of additional books. An additional $5,000 was given by Mr. and Mrs. Fiske to establish a permanent trust fund. Housed first in Stevens High School, the library moved in 1877 into the Bailey Block with more room and easier access. By 1902, space was again tight and Andrew Carnegie was approached for funding. In 1903, with $15,000 in funding from Carnegie, ground was broken for the present building. An addition in 1922 and a full renovation in 1966 expanded the entire building for library use.”

Interesting stuff, especially the mention of the Bailey Block. So I looked that up and found this:

“Across Sullivan Street, and defining the western edge of Tremont Square, is the Bailey Block (1826), originally a 2-story brick silversmith’s shop, 3rd story added 1878 as Fiske Free Library.”

Why isn’t there a sign on the building (or in front of it) that tells me that? Why did I have to do some research to find it out for myself? How many other people would bother to do that?

I could find out nothing noteworthy about the Dickinson Block, its history, or the current plans for it. My research came up with quite a bit about the Brown Block, since it’s been in the news a lot lately. Brown was Oscar Brown, but I’m not sure who he was. I found this on PoliticalGraveyard.com:

“Albert Oscar Brown (1853-1937) — also known as Albert O. Brown — of Manchester, Hillsborough County, N.H. Born in Northwood, Rockingham County, N.H., July 18, 1853. Son of Charles Osgood Brown and Elizabeth (Langmaid) Brown; married 1888 to Susie J. Clarke. Republican. Lawyer; president, Amoskeag Savings Bank, 1905-12; delegate to New Hampshire state constitutional convention, 1918-21; Governor of New Hampshire, 1921-23; delegate to Republican National Convention from New Hampshire, 1924. Congregationalist. Died March 28, 1937. Burial location unknown.”

He sounds like a worthy guy to name a building after. Maybe he’s the one.

Every town needs some things to remember, some things to look forward to, and some things that look like success. Claremont has all three. But for the first two, we could use a little more signage and information.

Among the places I discovered that looks like success is the Farro Deli, which is next to the Moody Building. I had my own taste of Claremont before I drove back home that day. I sat at one of their inviting sidewalk tables and enjoyed a great sandwich and the cozy ambience of Opera House Square. As I said, I love this place. I’ll be back.