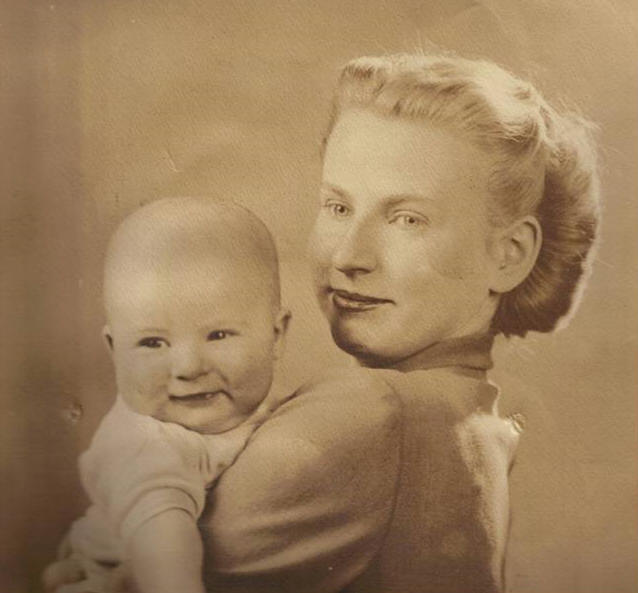

The first time I saw this photograph of Lynn Massman and her baby, I thought of my mother, who passed away four years ago this month (1-22-04). There are 75 photos of the Massman family on the Library of Congress website. They were taken for the Office of War Information. The caption for this one reads: “Lynn Massman, wife of a second class petty officer studying in Washington, D.C., giving eight-weeks-old Joey his daily bath.”

I first saw this photo and several others of this family on Shorpy.com, a marvelous site that has posted thousands of classic photographs, mostly from about 1860 to 1950, and invites comments and further information from readers.

My research, and some terrific work by other Shorpy readers, was submitted to the site and posted, piece by piece, eventually pasting together a few details about the life of the Massman family. And then something startling happened. Several of the Massman’s children found out what was happening and submitted further information, and a heartwarming testimonial to their mother.

Mrs. Massman bears a slight resemblance to my mother, Betty Manning, who would have been 25 years old when this photo was taken in December 1943. I would have been two years old, the first of two children born to Betty and my father, also Joe, who would have been 32 years of age. An Iowa native, and previously an employee of the federal government, Dad was serving in the Army then, and would be heading overseas shortly to fight in the war. He returned in early 1946, and enrolled in the University of Maryland, with the help of the GI Bill.

We lived for two years in government-built housing near the campus, and then in nearby Greenbelt, one of three Roosevelt New Deal planned communities. After Dad received a master’s degree in marine biology, we moved to southern Maryland, where my father worked for the State of Maryland, first as a biologist, and later as director of the Department of Chesapeake Bay Affairs. My mother went to work as a librarian when my brother and I were in our teens.

Like my father, both of the Massmans were also Iowa natives, but Lynn and husband Hugh grew up in Montana. Hugh enlisted in the Navy in 1942, and following the war, attended the University of Tennessee, where he received a law degree. He worked for the federal government for five years, and later for the State of Montana, before going into private legal practice. Little Joey was the first of eight children.

According to one of those children, Lynn was an expert seamstress, though she preferred being called a tailor. She taught sewing for many years, and later operated a tailoring shop in a department store. Active in the Democratic Party, she ran unsuccessfully for the Montana State Senate in the 1970s. Both she and Hugh married a second time. Hugh died in 2002, and baby Joe died in 2000.

Tragically, Lynn died of cancer in 1983, at the age of 61. One of her children commented on Shorpy.com, “She would have made a great old lady.”

In December 1943, when the Massman photos were taken, it had been two years since the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Victory for the US was more of a hope than a certainty. Like Lynn Massman and Betty Manning, there were millions of young mothers with small children who had struggled through the hardships of the Great Depression, and now had to face the loneliness of being separated from their husbands, and the fear of losing them in battle. In a long, tape-recorded interview I did with my mother seven years ago, she told me a story that points out the courage and fortitude women showed during this dark and often desperate era in American history. Since I am the interviewer, the “you” she refers to is me.

“I was pregnant with you when the Army sent your father to El Paso, Texas. I was living with his mother and stepfather in Beltsville (Maryland). You were born just before Thanksgiving, and your father had gotten Thanksgiving leave to come home and get me and take me to El Paso. But then he had to put his leave off till Christmas. Then war was declared on December 7th, so he was sent right away from El Paso out to a port of embarkation in Tacoma, Washington.”

“I couldn’t go, because they were just waiting there for ammunition to go overseas. So I stayed in Beltsville. He was in Tacoma until June. They never did get their ammunition, and he was sent out on a cadre to Riverside, California, to Camp Haan to train troops. Then he found a place to live, and he sent for me.”

“You were eight months old, and I took you out on the train. It took about five days, and I couldn’t get a bedroom on the train, but I had a whole section with two seats and an upper and lower birth. The seats faced each other, so I could put you on the other side. You slept with me in the lower birth. I had to take you to the dining car all the time, and you had to sit on my lap. I had a terrible time eating, because you kept grabbing at the food, and if you couldn’t have it, you would start crying, and I would finally have to leave.”

“When we got out to Cheyenne, Wyoming, there were several mothers on board with babies. The porter was so good. He used to warm all the bottles; then I would put you to sleep. We got into Cheyenne about midnight, and all the babies were asleep, and we were going to be there for about an hour and a half. And the porter said, ‘You four girls get off and go into the station and sit up at the counter a get a Coke or something and enjoy yourself. I’ll take care of the babies.’ So we did, and when we got back on the train, they were all crying.”

“I hadn’t seen your father for a year, and he hadn’t seen you yet. The porter kept saying, ‘I want to see that father’s face when he first sees that baby.’ We got into Riverside about nine o’clock at night. It was a long train, and I was way back in the Pullman, and the porter came back and said, ‘There’s no need for you to get off way back here. You come with me, and we’ll get off from the front of the train.’ He carried my luggage.”

“But your father was waiting back at the Pullman, and he couldn’t find me, and the train was only supposed to stop there for 15 minutes. So the porter had to get back on the train, and he didn’t get a chance to see your father. So when the train started to pull out, your father found me, and I told him how nice that porter was. And he said, ‘If I had known that and seen him, I would have given him a ten dollar bill.’ That was a lot of money then.”

My father died in 1981, leaving my mother a widow at the age of 62. She lived another 23 years, vibrant and youthful, as she enjoyed good times with her four grandchildren, nieces and nephews, and many friends. Mom, indeed, became a great old lady.

To see all of the photos of the Massman family in the Library of Congress collection, click the link below and enter “Massman” in the search box.

Library of Congress photo collection