“Our guardian star lost all his glow/The day that I lost you/He lost all his glitter the day you said no/And his silver turned to blue/Like him, I am doubtful that your love is true/But if you decide to call on me/Ask for Mr. Blue.”

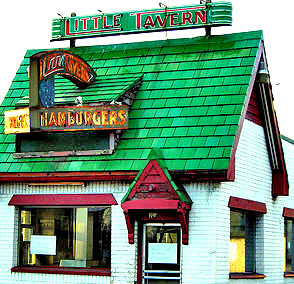

November 1959, College Park, Maryland: The soft, sad words of the Fleetwoods warm the tiny, nearly empty hamburger joint called the Little Tavern Shop. “Buy ‘em by the bag” is their slogan, and that’s what I do about 9:00 every evening if the chow at the University of Maryland dining hall leaves me hungry.

It’s chilly, so I take a seat at the 10-stool counter, order a hot chocolate, and chat with Homer, the little man with crossed eyes who listens to everybody, never changing his expression. “Yup, yup,” he nods, as he lines up a new batch of 10-cent burgers on one end of the grill and an equal number of rolls, face down, on the other.

“Three little ones and a bottle of Coke to go,” I call out, and drop two quarters on the counter. He hands me the bag. “See you tomorrow night.”

I head back to my room in Montgomery Hall, walking one block up on US Route 1, turning left through the gate, and then up the path a few hundred feet. The bag of burgers with the Coke sticking out of it sits on the palm of my left hand, while my right hand is wrapped tightly around the neck of the bottle. In the shadows near the dorm, I hear heavy, rapid footsteps behind me. As I glance around, I am surprised by a young man, who quickly snatches the bag and runs off, leaving me still clutching the bottle of Coke. Holding it like a tomahawk, I impulsively hurl it in the general direction of the escaping burger thief and hit him square in the back. He squeals and drops to the ground, then jumps up and staggers off, still clinging to his tasty meal.

**************************

I was born in Washington, DC, and spent my first few years in the quiet suburban towns that are mostly sprawl now: Beltsville, Riverdale and Greenbelt. When I was eight years old, my father, a marine biologist, got a job in Solomons Island, in rural Calvert County, where almost everyone’s dad was either a waterman or a tobacco farmer. It was beautiful, and heaven for kids like me who liked to ride bikes, catch blue crabs and play baseball all summer. But it was remote and parochial, endearing qualities only if you plan on sticking around there for the rest of your life.

I attended the all-white junior-senior high school, where everybody knew everybody, except that “everybody” barely filled the auditorium. There were just 77 in my senior class. I was a serious student, good in just about everything, especially math. So when I had the big pre-college meeting with the guidance counselor, she advised me to major in that subject. I was accepted to both colleges I applied to: Trinity (Connecticut), and the University of Maryland, my father’s alma mater, and the only one my parents could reasonably afford. So after a glorious summer – the Little League team my father and I coached won the county championship – my parents drove me up to College Park.

I met my roommate, a sophomore. In less than a week, I realized he was a total jerk, an oddball who made weird grunting noises constantly, stayed up all night reading magazines by flashlight, and showed no interest in me whatsoever. I had to do all the dumb frosh stuff, such as having to wear some kind of beany cap for a week, and singing football fight songs around a bonfire. It seemed like everybody I met was from Baltimore and had either gone to private schools, or those super big high schools I used to read about in the sports pages of the Baltimore Sun. All of them rooted for the Orioles, not the Senators, the Colts, not the Redskins, talked funny and seemed to peer at me with disdain.

Then I went to my first class. We met in this huge lecture hall, so big that you almost needed binoculars to see the instructor from the back row. There must have been 600 students. The professor introduced himself, and then said, “Welcome to Math 18. In six weeks, half of you will have failed your first exam and dropped out. The other half will wish they had.” There was some nervous laughter, even some sarcastic applause. It scared the crap out of me.

Math 18 was real math, “pre-calculus,” as the graduate assistant called it. I quickly found out that although I was great at arithmetic, I had no aptitude at all for conceptual math. So I flunked the course. I didn’t do that badly in my other courses, but at the end of the semester, they put me on academic probation.

I also flunked making friends. I was just a shy kid from the boonies. My whole county had only 15,000 people in it, and there were at least that many students living on campus, most of whom went home to Baltimore on the weekends. So after a couple of lonely Saturday night meals at the Hot Shoppe, I started going home, too. My parents obligingly drove up every Friday to rescue me, and I never looked forward to going back on Sunday. I felt anonymous and miserable. I clearly was not ready for the college experience. But come the second semester, I was back in class, this time majoring half-heartedly in journalism.

“I’m Mr. Blue/When you say you love me/Then prove it by goin’ out on the sly/Provin’ your love isn’t true/Call me Mr. Blue.”

October 1960, College Park, Maryland: The Fleetwoods are singing me into a state of melancholy at the Little Tavern Shop. I am back for another year. Calvin Griffith just announced that my beloved Washington Senators are moving to Minnesota, taking with them my heroes, Harmon Killebrew, Camilo Pascual, Jim Lemon and Bob Allison. What is there left to look forward to? More burgers by the bag? Talking to Homer?

But for a while, things got a little better. After all, I had made it through my second semester and two courses at summer school, and I had a new roommate – a pretty nice guy – and another chance. A week earlier, Bill Mazeroski had slugged that amazing ninth-inning homer, and the Pirates beat the Yanks in the World Series. And then John Kennedy got elected. I was even up to a “C” average.

But when I came back for the second semester, things took a strange turn for the worse. I stopped studying and started taking the bus into DC about three nights a week to see a movie – anything to get off campus and forget. One night I saw The World of Suzie Wong at the Town Theater on 13th Street, and was so smitten with the story that all I wanted was to be William Holden, the painter, romancing Nancy Kwan in Hong Kong. I went back the next night, and the next, nine days in a row, in fact. I bought the soundtrack and listened endlessly to George Duning’s beautiful score.

And then I stopped going to class. Finally I called my parents, and they came and got me. I didn’t even say goodbye to my roommate. It was a long ride home.

“I won’t tell you/While you paint the town/A bright red to turn it upside down/I’m painting it, too/But I’m painting it blue.”

March 2004, Laurel, Maryland: It is early in the afternoon. My wife and I are sitting at the counter in one of the last of the Little Tavern Shops. When I was a little boy, my grandfather used to take me up here for those little hamburgers every weekend. My mother passed away in Maryland two months ago, 23 years after I lost my father, and we are heading home to Massachusetts, after settling her affairs.

My thoughts go back to the Mr. Blue days at the University of Maryland. After I dropped out, I served in the Air Force four years. Then I returned to college, this time in Upstate New York, graduated, got married and settled in New England. It’s been 45 years since I left high school, and my 45th reunion is scheduled this fall. I haven’t seen the last of Maryland. I’ll be back in Solomons Island in six months.

As we were driving away, I suddenly thought about the guy who stole my bag of burgers. I wonder how his life turned out.

“Mr. Blue” was written by DeWayne Blackwell, © 1959, Cornerstone Music (BMI)