“As far as my Uncle Henry nailing his name in the floor, that sort of sounds like something he would do. He was a man with a great imagination. He always had a mischievous glint in his eyes. He always looked like Peck’s Bad Boy. He would be smiling at you like he had a secret he wasn’t telling anyone about.” -Jack Brooks, nephew of Henry Brooks

Do you know what you were doing on September 1st of last year? Or on that date five years ago? Maybe not, at least without some thought. But if someone had asked Henry Brooks what he was doing on September 1, 1923, he would have known right away, though he might have just smiled and said, “That’s a secret.”

On that date, now more than 88 years ago, Henry was working for the Hoosac Cotton Company, located at the Eclipse Mill, on Union Street in North Adams. When the boss wasn’t looking, he got out a hammer and nails and spelled out his name in the floor. It’s still there, 28 years after he passed away.

When artist Eric Rudd bought and renovated the Eclipse into artists’ lofts a few years ago, he saw Henry’s audacious autograph and decided to leave it there. “I saw lots of odd things like that in the building. They are part of its history, so I kept them,” he told me.

Sculptor Derek Parker and visual artist Anne Roecklein were looking to move into one of the units this summer and saw Henry’s “art work” near the kitchen sink. They met Anne French, who was at the Mill Children exhibit at the Eclipse Mill Gallery, and they asked her if she had any idea who Henry was. French contacted me, and pretty soon I was combing through census records and newspaper archives. It didn’t take long to track down Henry and his descendants.

It would have been about a three-minute walk to work for Henry the day he sort of made history. He lived with his parents in a row house at 9 Tannery Yard, just off Union Street. It’s a vacant lot today. His parents were Levi Brooks (born Onesime Rousseau, in Quebec), and New York native Mary (Varin) Brooks. They married in 1882. Levi had immigrated to the US in 1860, and lived for more than 40 years in the Lake Champlain area of New York.

According to the 1900 New York Census, Mr. and Mrs. Brooks were living in Bellmont, about 50 miles west of Plattsburg. They had six children, and Levi was a “day laborer.” On June 4, Henry Brooks (originally Henri or Henry Rousseau) was born in the nearby town of Standish. Five years later, the family moved to North Adams, where they rented an apartment at 264 Beaver Street. Levi worked at the Beaver Mill. By 1914, they had moved to 35 Union Street; two years later, they were at Tannery Yard.

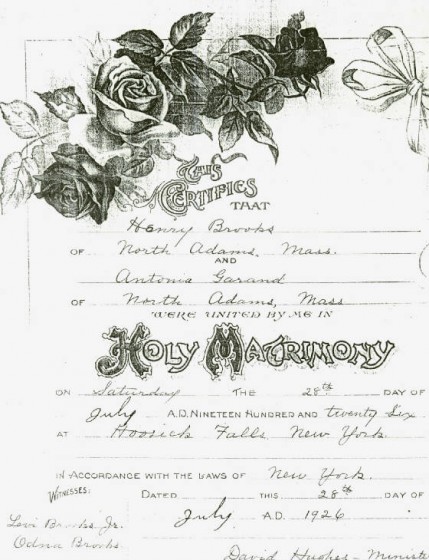

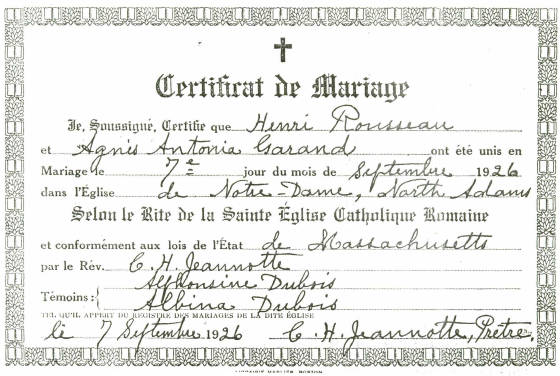

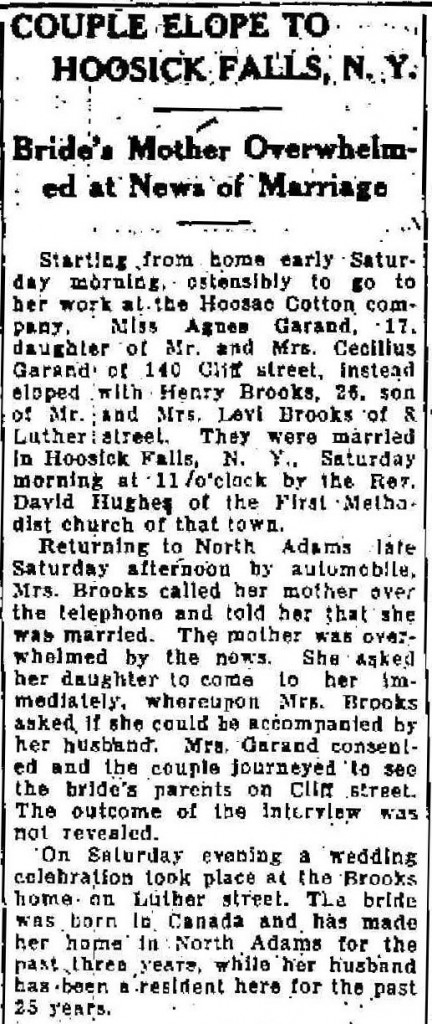

On Saturday, August 28, 1926, Henry married Agnes Antonia (Toni) Garand, of North Adams. One of her uncles, John Garand, invented the M1 rifle. Due to the unusual circumstances, they married again on September 7, at Notre Dame Church. They moved to 6 Tannery Yard, and Henry worked for the Boston & Maine Railroad. After renting for a while on Rand and Reed Streets, they bought a house at 135 Cliff Street, where they made their home for the rest of their lives.

Henry worked for Berkshire Fine Spinning at the Greylock Mill in North Adams for 23 years, and at Sprague Electric for seven years, retiring in 1965. Wife Toni died in 1970. Henry passed away on June 30, 1982, at the age of 82. They had two children, Robert, born in 1927, and William, born in 1931. Robert, who worked for General Electric in Pittsfield, died in 1966. William, now 80 years old, lives in Virginia. My interview with him appears below.

Both marriage certificates. The one on the right is in French and gives Henry’s name as Henri Rousseau.

Excerpts from my interview with William Brooks, son of Henry Brooks

“I grew up on 135 Cliff Street. My parents owned a second building at 147 Cliff. Before that, they had been living by the river, right down from the mill. I remember something about my mother falling in the river during one of the floods, and my father jumped into the river and saved her. ”

“Cliff Street was an excellent place to grow up. I walked to Notre Dame School. There were many children in the neighborhood who were my age. We liked to go up to Blueberry Hill, which was not developed at that time. There was a lot to do in North Adams then. You could skate and swim and ski.

“I worked for the North Adams Transcript from the time I was 11 years old until I was 19. I had a newspaper route with 140 customers. I had the Eagle Street, Union Street, Cliff Street area. Then I got a job inside. Jack Shields was the manager. I rolled up papers that we were mailing out. When I was 13, the man that was shoveling lead from the linotype and melting it into bars had some back problems, so they gave me the job. I was making $22.00 a week, which I gave to my parents.”

“My father worked at the Greylock Mill for 23 years. He always chewed tobacco to get rid of the cotton taste in his mouth. He was a shop steward. He went to Atlantic City once to represent the union. There was an ice skating rink right behind the mill that we used to go to. But in 1955, the mill closed down and moved south. In 1957, I came home from the service, and there was my father, a man who had all the talents of carpentry, electrician, plumbing, and he couldn’t get a job. We went looking together and applied at Cornish Wire, in Williamstown. I was 25 years old then and knew practically nothing. They hired me, but they didn’t hire him, just because of his age. So he finally accepted a job as a janitor at Sprague Electric. That had to be a letdown for him. But he had to take whatever job he could get.”

“I remember that every Saturday, my mother would buy him cigarettes and a bottle of bourbon. They would go out on Saturday night to either the Club Lafayette or the Eagles. They liked to go dancing. He did a lot of work around the house. He was very handy. My mother’s parents lived in one of the apartments downstairs. There were three apartments in the house. They had a swimming pool in the back yard. They had a couple of goats when I was a kid. Once in a while, my parents would go to Quebec to see some cousins. They had a nice life.

“After I graduated from high school, I served six years in the Navy. I was in France for four years because I could speak the language. I met my wife, Monique, in Paris. We married in North Adams. She worked at Richards Beauty Salon. In 1958, we moved to the Washington, DC area. My wife’s sister was married to a military person stationed in Alexandria. She opened a French restaurant there and offered me a job as a waiter. I managed a restaurant a couple of years later, and then I got into real estate, which I still do.

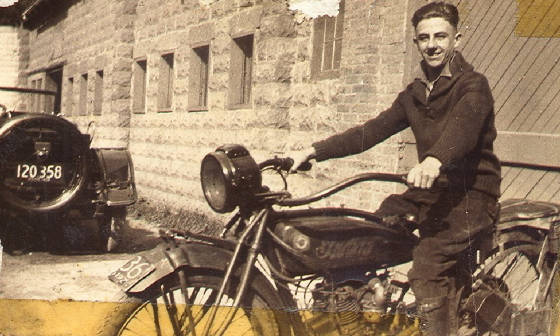

“My father had a good sense of humor, but it was still a minor shock to see what he did at the Eclipse Mill. But from what I had heard of his youth, the motorcycle riding and so on, I think it could have been something he would have done. I guess the moral is if you want to leave a legacy, don’t get the proverbial knife and carve into the wood. A hammer and nails is lasting.”

Some final thoughts

Derek and Anne are now residents of the Eclipse Mill. On a typical morning, sculptor Derek Parker, now a resident of the Eclipse Mill, heads into his kitchen, perhaps to fire up the coffee pot. On the floor, by the kitchen window, he sees what is perhaps the first work of art created at the mill, nailed into the floor by a 23-year-old cotton mill worker 88 years before Derek began to design and create his first sculpture in his new home. Derek and Anne have the luxury of working, uninterrupted, in their beautiful private studio along the Hoosic River. But Henry had to work in an impossibly noisy, lint-filled environment where he was under pressure to turn out a product as fast and efficiently as possible. How did he also manage to nail his name in the floor?

Many of my friends, and several of Henry’s descendants, have contemplated this question and offered their opinions. The general consensus seems to be that since his name is positioned right under the window, he might have been standing behind a machine or table, with his back to the window. He would have planned his deed in advance, so he could complete it in a short amount of time. When no one was looking, he grabbed a hammer and nails, turned around, knelt down and hammered away. The sound of his hammer would have been covered up by the clatter of the machines.

His deed was probably discovered soon after, unless it was partially hidden under some kind of shelving or table. But whenever it was finally noticed, there would have been little question who the culprit was. What happened when it was discovered? What did his boss say? Did he get into trouble? According to the North Adams directories, Henry continued to work in the mill for another three years.

After he left the Eclipse, he worked 23 years at what is now called the Greylock Mill or the Cariddi Mill. Then he worked at Sprague Electric, now the home of the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art. I wonder if there is another work of art by Henry on the floor of one of those mill buildings? Does anybody want to check this out?

“When Anne and I first saw our studio, it seemed like just an apartment. But discovering the name on the floor made us understand that the building had a history. We realized that there were people working here at one time. I think what Henry did is really art in its purest form. As an artist, I can speak to the fact that we all leave a little piece of ourselves behind. And that’s what he did. It’s been there a long time. It’s probably one of the more successful pieces of art, arguably more successful than anything I’ve ever made.” -Derek Parker