“Well there’s one kind favor I’ll ask of you/Well there’s one kind favor I’ll ask of you/There’s just one kind favor I’ll ask of you/You can see that my grave is kept clean.” -from a song by Blind Lemon Jefferson

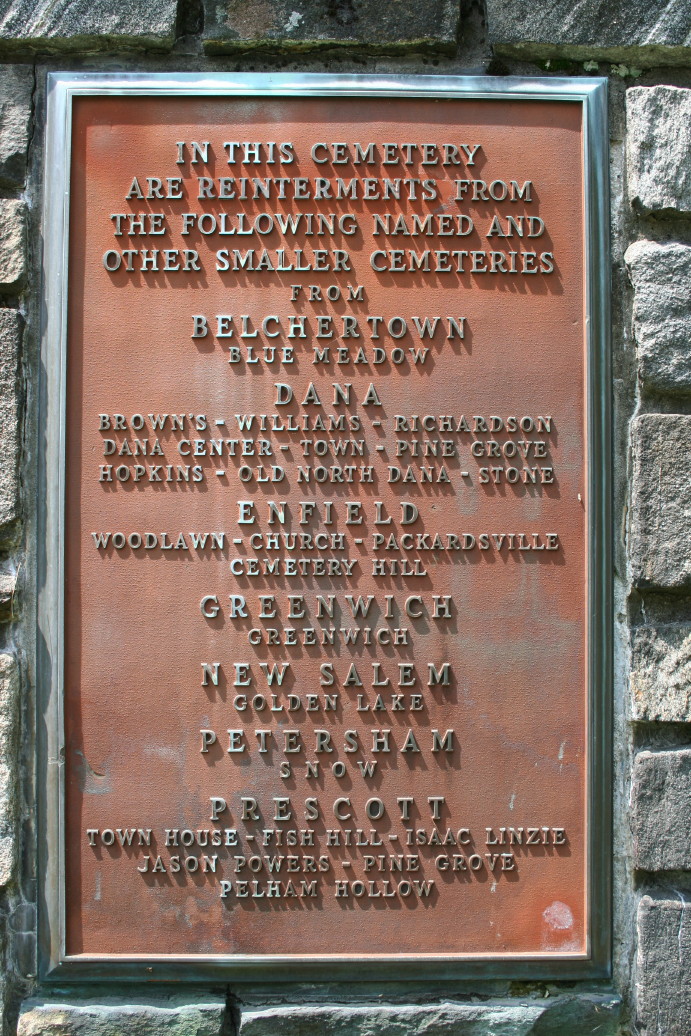

On July 31, 1927, Pulitzer Prize-winning editorialist F. Lauriston Bullard wrote a heartbreaking essay for the New York Times about the impending forced resettlement of several thousand residents of the Swift River Valley towns of Western Massachusetts: Greenwich, Enfield, Dana and Prescott. The state was planning to take control of the valley and construct two dams, which would direct water from the Swift River and the Ware River into what would become the Quabbin Reservoir, creating a supplemental supply for the Boston metropolitan area. Not only did the residents need to be relocated, but so did the graves and markers of their ancestors. Bullard’s eloquent words still haunt us 84 years later.

“The elms and lilacs, the apple trees and the pines, the farmhouses and the red brick schoolhouses, six churches and twelve cemeteries (the one at Greenwich with 1,500 bodies); some of the finest trout brooks in the State, ponds, roads, byways, woods, meadows, all are soon to disappear.”

Only 30 minutes from my home, the Quabbin Reservoir is the site of many scenic walking trails, providing my wife and me a lovely place to spend the day, especially in the fall. But until recently, we had never visited historic Quabbin Park Cemetery. We wandered around one morning, going from gravestone to gravestone. Just when we were getting a little weary of it, something caught our attention.

Right by the edge of the woods at the south end of the cemetery, next to a dirt road, was a tiny, solitary gravestone. As we approached it, we noticed that there was no inscription. But when we walked around to the other side facing the woods, we saw it, covered with dirt and lichen. It was very difficult to read, but we finally figured out what it said: F. Lloyd Adams 1893 – 1906. We wondered who the boy was, what caused him to die at such a young age, and why the gravestone was turned around the wrong way.

The next morning, I drove back with a jug of water and a soft brush and gently cleaned the stone.

When I got home, the search for F. Lloyd Adams began. I looked him up on FamilySearch.org, a well-known genealogy website. I found something right away.

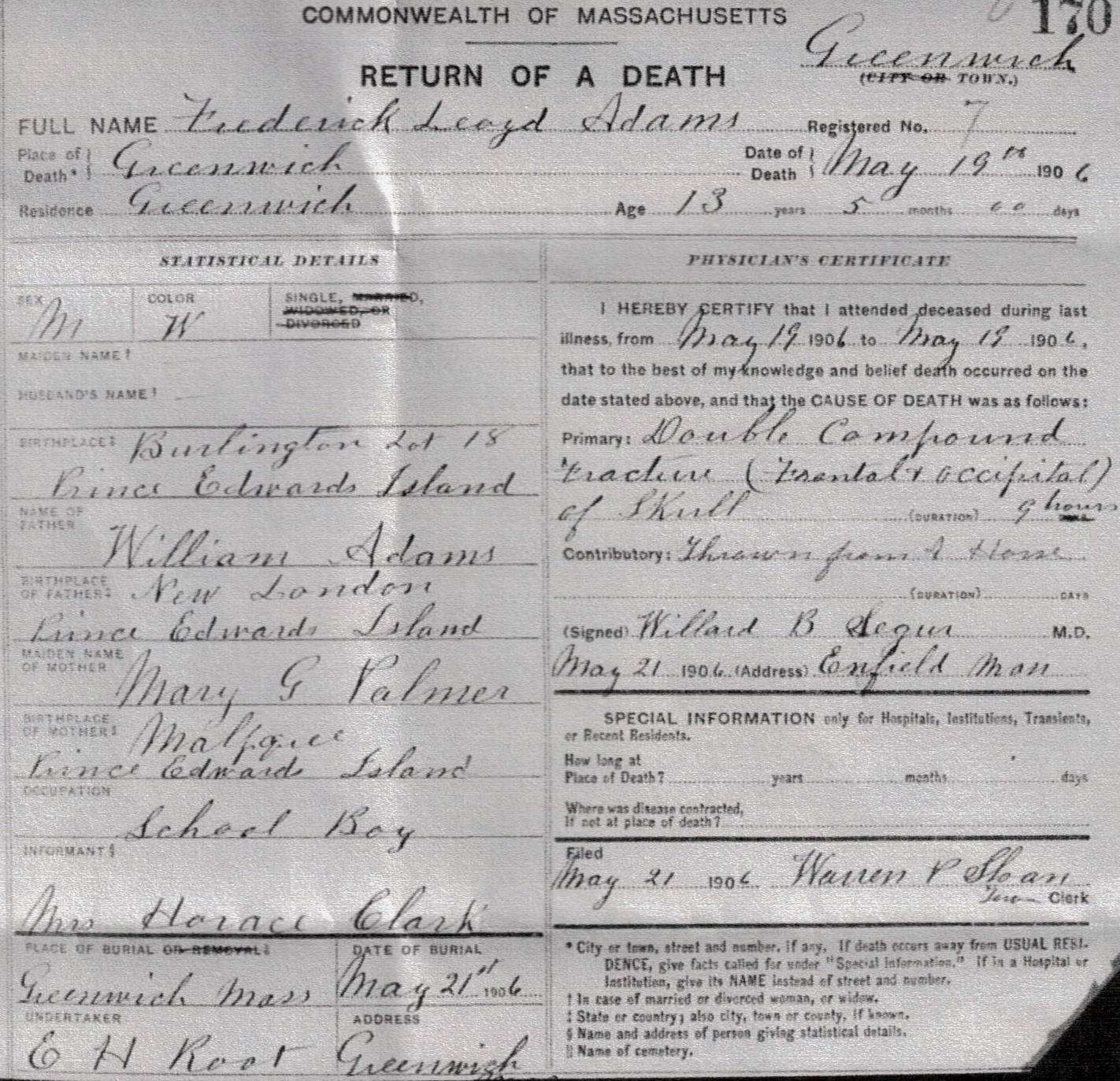

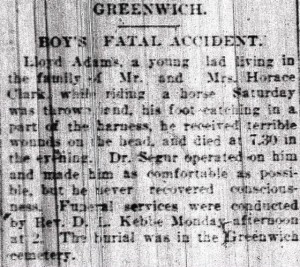

His Massachusetts death certificate popped up. It told me that Frederick Lloyd Adams was born in Prince Edward Island, his parents were William and Mary (Palmer) Adams, and that he died due to injuries sustained when he was thrown from a horse on May 19, 1906. The informant was a Mrs. Horace Clark, not his mother or father. I wanted to know more, so I headed to the Forbes Library in Northampton and searched the archives of the Daily Hampshire Gazette. Surprisingly, a report of the accident had been published.

But who were the Clarks, and why had Lloyd been living with them? Why wasn’t he living with his parents? And how did he wind up in Greenwich, some 700 miles away from his Maritime roots? I headed back to the genealogy websites and found some clues. Someone had posted some of the Adams family tree on Ancestry.com.

According to the author of the family tree, Lloyd was born on January 27, 1893. His father, William Thomas Adams, was born in New London, PEI, in 1852. Lloyd’s mother, Mary Clara (Palmer) Adams, was born in New London, in 1861. They were married in Alberton, PEI, in 1882. They had nine children, the first born in 1884, and the last born in 1901. Two years later, on January 8, 1903, William died (according to another source, he died at sea). Lloyd was nine years old.

Although Lloyd’s death date was listed correctly as 1906, the location was not mentioned. The author’s contact information was listed, so I emailed him a copy of the story about the accident, and a photo of Lloyd’s gravestone. He replied promptly with great interest. He knew nothing about what I had just found. His name is Fred Adams, and he is the son of Lloyd’s brother Leaman, who was born in 1899. I called him up, and he had some interesting information.

“When my grandfather died, the family was pretty destitute. He had been a farmer and a handyman. He didn’t own any land. My grandmother was left to support the children, but she had no assets or income. So she just started farming them off to different families. My dad went to live with a neighboring family. During World War I, he served with the Canadian forces and was in France and Germany. After the war, he traveled all across Canada, working in various jobs along the way, and ended up in Saskatchewan, where he worked as a farm laborer. In the winter when there was no work, he stayed on the farm, where he was provided bed and board, but no wages. At some point, he got into construction and then went to Nevada, where he worked for the railroad on the tunnel systems. He died in Las Vegas in 1964 when I was 20 years old.”

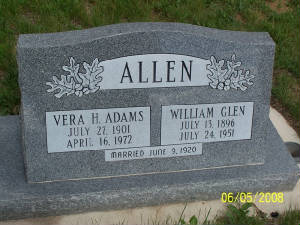

He told me that Vera, the youngest child, went to Utah soon after her father died, but he has no idea why she went there or how she got there. Her mother followed her to Utah later, where she married again in 1909, to George Day. All the other children eventually came to the US, except Alice, who died in PEI in 1987, and Melbourne, who lived only a year. Mary died in Utah in 1945. Vera died in Utah in 1972.

I found Mary and George Day in the 1910 census, living in Fillmore, Utah. Also in the home were Mr. Day’s five children from a previous marriage. Mary’s immigration date was listed as 1904. I wondered if she might have come to the US with Lloyd. She does not appear in immigration records, nor do any of her children.

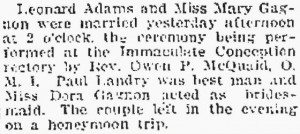

Then I found a military record showing that Lloyd’s brother Leonard, who was born in 1885, enlisted in the US Army in 1908. He was living at the time in Lowell, Massachusetts. I also discovered his Massachusetts marriage record. He married Mary Gagnon in Lowell on October 3, 1915. He was listed as a carpenter, and his wife was a mill operative.

I wondered if he might have come to Massachusetts with Lloyd and his mother, and somehow Lloyd wound up in Greenwich and his mother went to Utah. I could not find Leonard in any US censuses. He died in California in 1967, according to the Social Security Death Index.

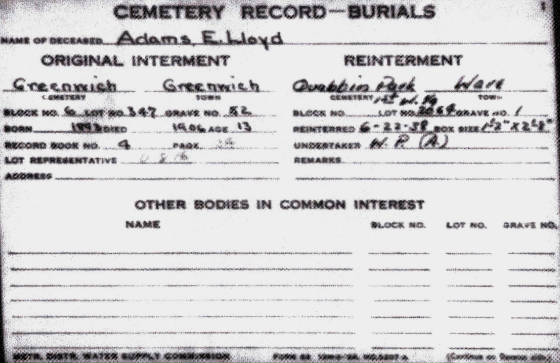

Several questions were still unanswered. Why did Lloyd go to Greenwich, and who were Mr. and Mrs. Horace Clark, the couple he lived with? I headed to the Quabbin Reservoir Visitors Center, where there are records of Greenwich and the other Quabbin towns. I found Lloyd in the burial records.

I also found some information about Horace Clark. According to the 1906 tax assessment records for Greenwich, Horace and his wife Naomi owned a farm. Here is how the assessment broke down.

Three horses: $200; 17 cows: $500; two yearlings: $40; two carriages: $50 and $790; house: $350; barn: $450; store house: $100; farms: $80 and $950; Shaw cottages: $25 and $250; Clark farms: $100, $600 and $2700. Total tax: $48.86.

There was a large book of old photos of the area. Several of the pictures were of Hillside School, in Greenwich, described as a school for orphans and homeless boys. It taught a number of vocations, including farming. It was established in 1901, but moved to Marlborough, Massachusetts in 1926, due to plans to build the reservoir.

The school still exists, although its mission is somewhat different. I wondered if Lloyd had attended the school, and if that was the reason why he went to Greenwich. I also wondered if he had the horse accident while participating in the school’s farm program. I talked to a helpful employee at the Quabbin Administration Building, and he told me that Lloyd could have attended the school, even though he was living with the Clarks.

Back at home, I searched for more information about the Clarks, and found Horace in the census as far back as 1840.

According to The Leading Citizens of Hampshire County, published in 1896, Horace was “one of the town fathers of Greenwich, Mass., a village resident actively engaged in general farming and cattle dealing.”

About 1850, after serving in the military, he moved to Lynn, Massachusetts, where he established a morocco leather factory, which he operated for 28 years. He moved to Greenwich in 1878 and purchased a farm.

“This farm, which covers two hundred acres, is one of the best in town. He carries on general farming, and makes a specialty of fattening veal for the Boston market, keeping from ten to twelve cows to aid in feeding the calves which he buys. The dwelling-house which Mr. Clark occupies is one of the oldest in the town, having been erected in 1766, and widely known as the old Hines Tavern.”

Clark married three times, the first two dying at a young age. In 1888, he married Naomi Dutton. According to the 1880 census, she had been his housekeeper.

“In politics Mr. Clark is an independent. He has held nearly all the public offices of the town of Greenwich, serving as Selectman, Overseer of the Poor, and in other capacities; and in educational matters he is a moving spirit, his great desire now being to see a high school established in Greenwich.”

He sounded like the kind of person who would have offered to take care of Lloyd. I later talked to Joe Russell, noted author of three books about the Quabbin area. He told me that Clark had a reputation for being very generous and would have gladly taken in the boy, since it would have also resulted in having an additional farmhand.

Horace died in 1908, two years after Lloyd’s fatal accident. He was 88. Naomi died in 1916 at the age of 65. Both are buried at Pine Grove Cemetery in Lynn.

I contacted Hillside School in Marlborough to see if they had a record of Lloyd. Sadly, I was told that shortly after the school moved, the new administration building burned down, and all the records were destroyed. I also talked to noted photographer and archivist Les Campbell, who provided me with several of the photos in this story. He told me that he talked once with a former resident of Greenwich who lived in the town in the early 1900s. The person remembered that the farm boys at Hillside School would ride around on their horses with reckless abandon. Perhaps Lloyd was one of them. He might have been one of the boys in the photo below.

So I was down to one unanswered question. Why did Lloyd go to Greenwich?

I could find no town, census, or genealogy records that indicate he was related to anyone there named Clark or Adams. So that leaves me to speculate the following scenario:

When Lloyd’s father died in 1903, Lloyd was almost 10 years old. His brother Leonard was about to turn 18. It was common in the late 1800s for able-bodied young men to leave eastern Canada and look for work in the many textile mills of New England. So Leonard might have headed to Massachusetts about 1904 (Mary’s stated immigration year) and brought along his struggling mother and his young brother Lloyd. Perhaps they went to Lowell. At some point, they heard about the Hillside School and took Lloyd there, where he was taken in by the Clarks. Not long after, they learned that Lloyd had been killed.

After Leonard joined the Army in June of 1908, his mother decided to join her 7-year-old daughter Vera in Utah, where she met her soon-to-be second husband. When Leonard and his wife finally left Massachusetts, there was little chance that anyone in the family would ever visit Lloyd’s grave again. In 1938, with Greenwich nothing but a memory, the grave was moved and Lloyd was thrust into obscurity, the carved letters of his name, and year of birth and death, facing unnoticed into the woods.

There was one more thing I wanted to do. I wrote to Bill Pula, the regional director of the Quabbin Reservoir and the cemetery. After telling him about Lloyd, I wrote: “I would like to ask if you can have the stone turned around so that the inscription faces the correct way. I feel that young Lloyd should be remembered.”

I called him a few days later. He thanked me for the request and told me that the cemetery foreman had just turned the stone.

Official site of Quabbin Reservoir