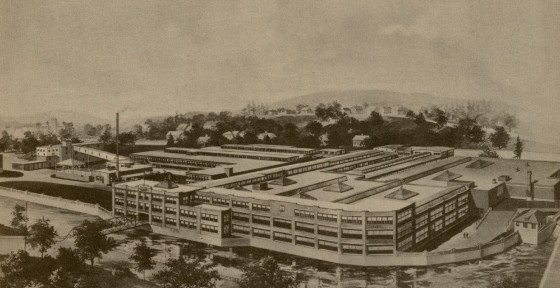

At the lower end of Rita Street, in Springfield, Vermont, there is a short, steep path through the woods that leads down to the intersection of River Street and North Main Street. Just across River Street is a footbridge that crosses the Black River and connects to the front entrance of the former Fellows Gear Shaper factory, now the home of the Springfield Health Center, which provides many outpatient services. It opened in September of 2012. There is also an adjoining art gallery called the Great Hall, and plans for other tenants. The footbridge is new. In August of 2011, the old bridge was replaced after enduring billions of footsteps over a period of more than 100 years. More about the redevelopment of the Gear Shaper plant at the end of this story.

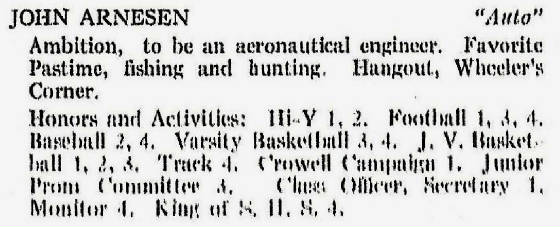

In the 1930s, Springfield native John Arnesen, now 85 years old, often walked a short distance to Rita Street from his home on Ellis Street, and then took that same path down to Fellows to visit his father at work. At that time, there were no woods there, just a few trees at the bottom. He remembers one visit that didn’t work out so well.

“In the morning, you would see all sorts of men, including my father, getting on that path. One time it had been raining, and the path was very muddy. I was about five or six years old then. I was on my way down, and I got stuck in a mud hole and walked in with only one shoe on.”

His father was Otto Harold Arnesen, who was born on Deer Island, in New Brunswick, Canada, on June 24, 1894. He married Ida Richardson in 1916, and they came to Springfield the same year. They had their first child in 1917. Shortly after, they moved to Eastport, Maine, right across the bay from Deer Island. Otto worked in a fish cannery. But by 1921, they were back in Springfield. John, born in 1927, is the youngest of five children. He currently lives in Marshfield, Vermont. I had an enjoyable phone conversation with him, as he reminisced about his family and his hometown.

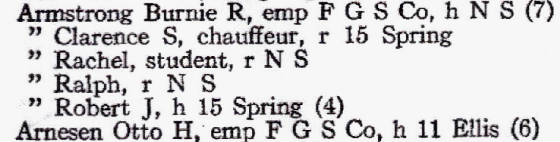

“My father worked at Gear Shaper when I was growing up, but he had worked for a short time at Parks & Woolson earlier. He was a machinist at Gear Shaper, and an inspector the latter years of his employment. We lived at 11 Ellis Street, up off Elm Hill Street. The house had been moved from Hardwick (Vermont). My parents bought it in 1924. It was a two-story, four-bedroom house. That area was loaded with elms then, but in 1938, they all came down in the hurricane.”

“When the Depression came, they closed the plant. Fortunately for my dad, Gear Shaper gave him a job as a night watchman. Dad was making only $7.50 a week. They couldn’t pay anything on the mortgage. My mother had to take in roomers. When they finally started paying again, they owed more than the house was worth. In 1937 and 1938, when the Germans and Italians started the war in Europe, the other European countries started tooling up and needed machines, so Springfield was pulled out of the Depression, and my dad went back to work full time as a machinist.”

“In 1944, they sold their house and moved to an apartment 200 yards away. They rented the second floor of the Hitchcock house. Then they bought a home at 6 Curtis Street (just a short walk from 11 Ellis St), although in between, they lived for a while in my older sister’s house on (123) South Street. They stayed on Curtis Street until my mother passed away in 1966. My father had just retired. They owned a house on Deer Island. My mother had inherited it from her sister. They were getting ready to go up there and live, and then she got cancer and died.”

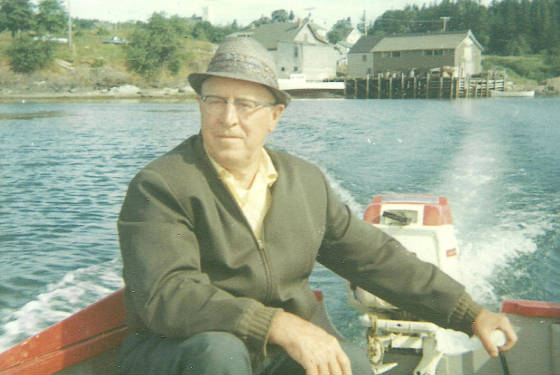

“My dad married again, to Winfred Butler, an old school chum. They lived on Deer Island for 25 years. We had a big reunion up there for my dad on his 80th birthday, and then we had 18 more reunions after that, because he lived to be 98. Winfred also died at age 98. My father’s ashes were interred at a cemetery on Deer Island.”

“He had been very active in the Calvary Baptist Church in Springfield, so my sister had a memorial service for him there. It was packed. My father loved to fish and hunt, and he had all kinds of friends who came. Most of them were 15 or 20 years younger than he was, and had worked with him at Gear Shaper. Many of them came up to me and told me how much my father had helped them at the plant. In addition, they all had hunting and fishing stories.

“I had three sisters and a brother. My oldest sister (Frances) graduated from high school in 1935, and then she enrolled in nurse’s training in Boston. I had an uncle who was a pilot in the Boston Harbor and made big money. I suspect he paid for my sister’s education. Another sister (Genevieve) became a secretary, and the other (Charlotte) enrolled in a theological school, but later got married and became a housewife. My brother (Arne) flew sixty missions in WWII, then got a master’s degree in physical education, and was the track coach at the Air Force Academy.”

“I went into the Army in 1945, and when I got out, I got the GI Bill and went to Spartan College of Aeronautical Engineering, in Tulsa, Oklahoma. When I graduated, I went to work for Chance-Vought Aircraft Company in Dallas. I left in 1953, came back home, and went to work for Bryant Chucking Grinder. At that time, the machine tool industry was already beginning to fade in Springfield. My brother-in-law, who was one of the higher-ups there, told me one day, ‘We’re having trouble. We’re not getting a lot of orders. You’re new here, and you don’t have any seniority.’ At the same time, Chance-Vought opened an office in Boston and offered me a job there. I took it. When I gave my notice, Bryant told me they were laying me off anyway. I moved to Waltham (Massachusetts), and then bought a house in Framingham. Then Vought was bought by Pratt & Whitney, and I worked for them in Hartford (Connecticut).”

“Springfield was a bustling town during the war. The town was supplying jobs for people up to 40 miles away. The plants were running 24 hours a day. The bowling alleys and restaurants stayed open all night. When I was 15, I got a job in Wheeler’s Drugstore. At lunchtime a lot of guys came in and drank a frappe and ate crackers, and then they would go home at night and have their big meal. That was a busy time when you had to get ready for their hour off. The place filled up fast. Most of them stood up at the counter because there were only a few tables. I had a school friend who worked with me, and we could handle the soda fountain real well. He’d stand at one end of the counter and I would stand at the other, and we could throw the glasses back and forth. We enjoyed it.”

“I remember the 1938 hurricane. My uncle had taken us out for a drive on a Sunday afternoon. When we came back, the wind was blowing and we were blocked by a big tree. One of the trees was leaning way over. We drove under it after my uncle was able to break off a limb. There was a man named Mr. Bamford who had a lot of apple trees that he had fenced off so we couldn’t steal his apples. But the wind blew a lot of the apples over the fence and onto the ground. So a neighborhood friend and I stood out there in the wind with paper bags and collected apples. We took them home.”

“The high school had a co-op machine tool course, where you learned to run machines when you were a freshman. They had a machine shop, and various plants had donated machines to them. When you became a sophomore, you were assigned to go to work in one of the plants, so you did actual work. It was six weeks on the job, and six weeks in school. I was assigned to Jones & Lamson.”

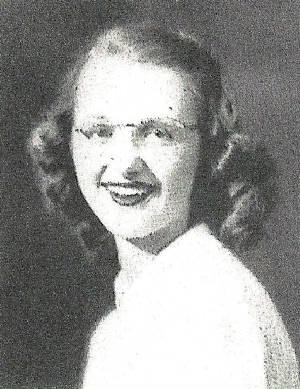

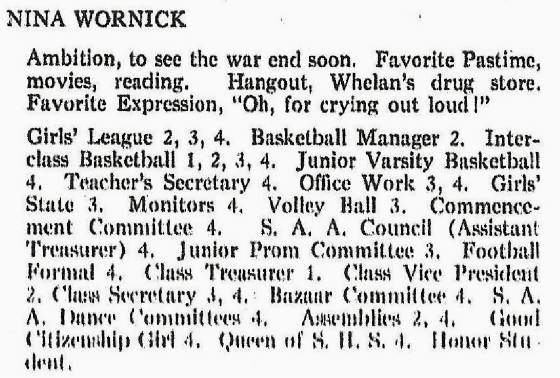

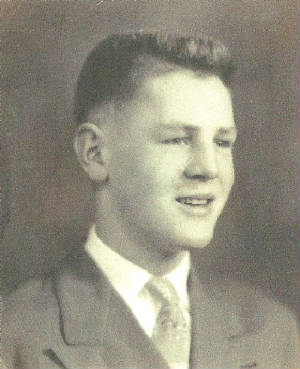

“I was king of Park Street School in my senior year. They elected a king and queen every year. I was very surprised. The queen was Nina Wornick, who was a good friend, but not a girl friend. They had a big celebration in the gym and crowned us.” (Nina Wornick Lindstrom passed away in Springfield, Vermont on January 26, 2006, at the age of 78).

After our conversation, I was eager to walk that steep dirt path that John had walked many decades ago. Early one cool, dreary October morning, I drove into town from my home in Massachusetts. It was a good day for a curious writer with a camera. The red brick buildings, faded wooden street level facades, and even the river take on richer colors when there is no sun to polish them up. I drove up Elm Hill Street, parked near the Arnesen house at 11 Ellis Street, and walked around the neighborhood.

I was enchanted by the modest houses scattered along quiet streets, many impossibly steep. The day before, I had looked in the Springfield directories (online at Ancestry.com) between 1920 and 1950. It was no surprise that many heads of households on these streets had “F G S Co” after their names. I could almost see the workers coming out of their houses and marching down to Gear Shaper in the early morning or trudging back home at suppertime.

I drove back down Elm Hill Street, parked downtown, and walked up to what is now the Springfield Health Center parking lot facing the river. While I stood there and took a few pictures, a number of people drove in, got out of their cars, and walked across the bridge and into the Health Center. I followed along behind a mother with a young daughter who was wearing a bright pink coat. Perhaps they had a date with the pediatrician.

It was gorgeous inside. I was awed by the richly appointed woodwork, the heavy doors and the nostalgia inducing staircases. They come from an era when both beauty and function were the products of the same proud hands. Older visitors who remember the heydays of the machine tool industry are likely to find themselves reminiscing as they wait to see the doctor or lab technician.

On the second floor, there is an exit that goes through the Great Hall art gallery and out to the designated parking area off Pearl Street. That means that visitors entering the Health Center from there will immediately be confronted with a magnificent gallery carved out of what used to be a noisy, chugging machine shop.

When I left to go back downtown, I crossed the footbridge once again. I stared up at Elm Hill and wondered what it looked like to Otto Arnesen when he walked home after a long day. I stared at the Black River and watched it rush toward the dam. I thought about the last words that John told me in our conversation.

“I have no family left in Springfield, but I go back every year to see friends, and we have a high school reunion every five years. My father died 16 years ago, and he lived his final 25 years on Deer Island. So other than a couple of my old friends, I doubt that there’s anyone left in Springfield who would remember him.”

“I had a summer job at Gear Shaper in 1950, when I was going to college. I did some drafting for them. I have fond memories of working in there and looking out the windows at the river. I think it’s a great thing that they are finally using the buildings again.”