Lewis Hine caption: Allen Chaffey, 9 years old, 37 Clark St., Eastport, Me., helps mother pack in Seacoast Canning Co., Factory #1. Walter Omar, 8 years old, 4 Clark Street, cuts. Location: Eastport, Maine, August 1911.

“Allen was pretty middle class all his life. He was very frugal, almost to the point of being stingy. I mean, right down to how often you flushed the toilet, or how often you took a bath. He watched every penny. So you knew when you got a gift from Allen, it was very treasured. He worked very hard, and I think that came from this factory work and living in a poor town. All of his friends were in the same boat. Everybody was working hard, but it wasn’t a bad thing. He didn’t know any different. If he hadn’t been working as a child, he’d have been home alone with nobody to play with, because all his friends would have been working.” -Eileen Dougherty, niece of Allen Chaffey

“Since I saw the Lewis Hine photo, I’ve gotten more sympathetic towards him, and I think I understand why he behaved the way he did, and why he didn’t share his past with me. I think that sometimes we don’t recognize that people feel shame about things they don’t want anyone to know about. So you get people like my father, this tremendously self-sufficient, very abrasive man, very determined.” -Helena Frey, daughter of Walter Omar

According to the caption, Walter was a fish cutter, and Allen helped his mother with the packing. Some of the most alarming of the Lewis Hine photos taken in Eastport depicted children with cut fingers or wielding butcher knives. That was Walter’s fate, an obviously risky situation for an eight-year-old boy. It is not known if Allen also became a cutter. However similar their situations might have seemed then, my research reveals that the two boys grew up to experience very different lives.

What difficulties were these children faced with at the cannery? There is considerable disagreement about that. Several years before this photo was taken, there were three serious investigative reports published, portions of which appear directly below. Following that, you will see the stories of these two boys.

Lewis Hine caption: Shows the way they cut the fish in sardine canneries. Large, sharp knives are used, with a cutting and sometimes a chopping motion. The slippery floors and benches, and careless bumping into each other increase the liability to accident. “The salt gits in the cuts an’ they ache.” Location: Eastport, Maine, August 1911.

In The Bitter Cry of the Children, published in 1906, author John Spargo wrote about his investigation of child labor in the fish canning industry in the Maine towns of Eastport and Lubec.

“In Maine the age limit for employment is twelve years. In 1900 there were 117 establishments engaged in the preservation and canning of fish. This industry is principally confined to the Atlantic coast towns – Lubec and Eastport, in Washington County, being the main centers. I cannot speak of this industry from personal investigation, but information received from competent and trustworthy sources gives me the impression that child slavery nowhere assumes a worse form than in the sardine canneries of Maine. Says one of my correspondents in a private letter: ‘In the rush season, fathers, mothers, older children, and babies work from early morn till night – from dawn till dark, in fact. You will scarcely believe me, perhaps, when I say ‘and babies,’ but it is literally true. I’ve seen them in the present season, no more than four or five years old, working hard and beaten when they lagged. As you may suppose, being out here, far away from the center of the state, we are not much troubled by factory inspection. I have read about the conditions in the Southern mills, but nothing I have read equals for sheer brutality what I see right here in Washington County.'”

**************************

In the Twenty-first Annual Report of the Bureau of Industrial and Labor Statistics for the State of Maine, published in 1907, Eva L. Shorey, a special agent for the agency, took strong exception to Spargo’s comments. In part, she wrote:

“Mr. Spargo makes an affidavit as to statements in the book which came under his direct notice, which, of course, did not include this. It is unfortunate that his personal investigations did not extend to Maine, for we are very sure, if they had he never would have permitted such a statement to appear in his book. The labor law has been changed since this was written, the age limit now being fourteen years. It should be stated that there is an exception in regard to factories dealing in ‘perishable goods,’ which permits children of any age to be employed, subject to the supervision of the factory inspector.”

“There is, however, no comparison between the southern mills, or any mills, and the sardine factories. Most of the work in which the children are employed is done practically in the open air, and not in hot, stifling, noisy rooms; there are no regular hours, the work depending on the amount of fish received. In the ‘rush season,’ there is an immense amount of work from the nature of the business, and the factory owners often have great difficulty in finding enough help. This does not last very long, the entire season being seven months and the busy time from the last of August to the middle of November.”

“There is no ‘slave driving.’ The young children come and go as they wish. It may not be very attractive or desirable work for one of tender years, but it is honest and healthy and does not continue day in and day out nor for any great length of time consecutively. The children appear to enjoy it and are very proud to tell how many boxes they have cut.”

“After observing the work in the different factories, I questioned many people who had lived in Eastport all their lives as to their knowledge of the work of the children. I could not find a person who had ever seen or heard of any of the brutal conditions described. They were all quite aghast at the statement.”

“It is true young girls and boys are employed to a certain extent, some in cutting the fish, an occasional one as a packer or helper, and boys work at the machines. Much of this is, however, not during school time. The factories are open about four months of the school year, the most work coming during the fall term. A person who has been connected with the Eastport schools gave as his judgment that the children out of school and in the factories were there from necessity and not from choice. One gentleman, who has made something of a study of this matter, said, in his estimation, 45 per cent of the children left school during or at the end of the grades and did not attend any institution of learning after becoming fifteen.”

But later in the report, Shorey expresses her own serious reservations about the conditions.

“It is not the work or the earning of money which is to be deplored. It might be well if there were more of this, but the harm comes in doing it at the expense of the education so freely offered by the towns. It is a most unfortunate situation that these children are out of school so much of the time.”

“One sad instance occurred in October, when a boy of nine years, working at a machine in one of the factories, caught his hand in such a way that it was necessary to amputate the first and second fingers of the right hand. Meeting the boy a few days later, as he was wandering about the factory, his arm in a sling, he told me his home was in a neighboring town, that he was one of a family of six and his people came to Eastport during the sardine season. He had been earning $1.50 a day, feeding cans into a machine. He looked away a minute, the cover slipped, he put out his hand to straighten the tin, and the machine caught his fingers. The foreman stopped the machine, else the whole hand would have been crushed. ‘Well, what now, my boy?’ I said. ‘Mother says I’m to go to school and learn to do something else. Maybe I can keep a store when I get big enough,’ – the ambition of many a youth. ‘I’ve just got to make the best of the pain, I suppose,’ added the little philosopher, who must go out to fight the battle of life with a maimed right hand. Had Mr. Spargo’s informant said, ‘Small boys should not work at machines, their little fingers are not sufficiently trained to keep away from the hungry cogs,’ many would doubtless have agreed with that sentiment.”

**************************

In 1909, the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) published an account of the proceedings of their Fifth Annual Meeting. Included was Child Labor in the Textile Industries and Canneries of New England, a chapter by Everett W. Lord, New England Secretary for the NCLC. He wrote in part:

“The one industry in New England in which children are practically without legal protection is the canning industry in Maine. By an unfortunate exemption the law relating to child labor is made inapplicable to any manufacturing establishment the materials and products of which are perishable.”

“Years ago I visited a canning factory in which there were packed three different products, French sardines, brook trout, and mackerel, all of them being known as herring before they were canned. The fish are gathered in seines and weirs, and are taken in motor boats to the nearest factories. As soon as a load of fish is received at the factory the herring are taken out, cut to the required size, and placed upon flakes for drying and cooking. The cutting and flaking is commonly done by women and children. The fish must be cut and cleaned as soon as they are delivered at the canneries. This may be in the early morning, or at any time during the day or evening, or even late at night. When a boat arrives, the cannery whistle blows for cutters, and whether they are at play in the streets or asleep in their beds matters not, the call must be obeyed, and the children go in troops to the shop. If work begins late in the day it may last until late at night, and in consequence it is not uncommon to see children of eight or ten years of age returning home from their work at midnight, perhaps to be called out again in the gray of the early dawn.”

“None of the work is particularly exhausting, and the rooms are usually open to the air. At the same time, the operatives frequently work long hours, as it is customary to can all the fish which may be at hand before stopping. In the busy seasons the factories sometimes run fifteen or sixteen hours at a stretch, and women and children remain as long as the factory is open. The surroundings, especially in the cutting room, are likely to be disgustingly dirty, but they are perhaps not unhealthful. The chief menace to the health lies in the irregularity of work and corresponding irregularity of home life.”

“It is impossible to say how many children are working in these canneries, but as a conservative estimate I should say that during the busy season not less than a thousand children under fourteen years of age are so employed. There are a good many children as young as eight or nine who work in the flaking rooms. These little ones do not always remain throughout the entire day, but as they are paid by the piece some of them stay until they have earned enough to satisfy them for the day, and then go to their homes. Others, either because of their own desire or because they may be required to remain, work as long as the fish last.”

“In many of the sardine factories much machinery is used; the law does not require the safeguarding of this machinery as it does in other factories, and a child worker has to take upon himself ‘the risks of his employment.’ If he is injured, the employer is not liable for damages. In one instance, recently reported, a girl, only nine years of age, lost her hand while playing about a drier. No damages could be recovered; the girl was supposed to know that the machine was dangerous, and had no business to be playing near it.”

“Sardine canning is a seasonal industry, and this is urged by some as extenuation for the employment of children. They say the children are engaged only during vacation seasons, and so are not necessarily deprived of school facilities. The season, however, lasts from April 15 to December 15, leaving only four months of the year when the children are free from the call of the factory. As a matter of fact, I believe that this seasonal employment is one of the worst features of the business, involving as it does a long period of idleness, and setting before the children the example of their elders, who quite commonly rely upon their season’s work for their entire support.”

******************************

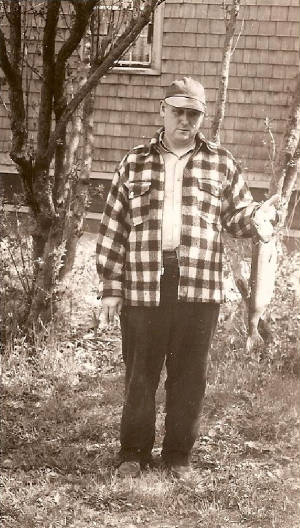

Allen Chaffey

According to official records, Allen Guy Chaffey was born in Eastport, Maine, on March 4, 1903. He was actually eight years old in the Lewis Hine photo, not nine as Hine stated. His parents were Guy and Grace (Balkam) Chaffey. He married Leona Dudley on October 20, 1938. They had no children. He died in Calais, Maine, on August 2, 1977, at the age 74. He is buried in Hillside Cemetery, in Eastport. From the obituary of his brother, Guy, I was able to locate Eileen Dougherty, Allen’s niece, who remembered her uncle fondly.

Edited interview with Eileen Dougherty, niece of Allen Chaffey. Conducted by Joe Manning (JM), on January 2, 2008. Transcribed by Jessica Sleevi and edited by Manning.

JM: You told me that you had seen the picture before. When did that happen, and under what circumstances?

Eileen: There was a display in Eastport over the Fourth of July a few years ago.

JM: Were you surprised?

Eileen: Yes.

JM: Did you know that he would have worked at the cannery at that age?

Eileen: No, he never talked about it. My parents knew, but they hadn’t talked about it either. Actually, it was my mum (mother) who told me to go look at the picture. When I saw it, I was quite shocked, because he never spoke of it, but he always was very interested in the factory life. For instance, when I worked as a teenager in the factories, he was very interested that I was doing that. Often I would go to his house for my dinner break and we would talk about my day’s work while we ate shrimp sandwiches. He was a special uncle.

JM: He looks awfully young, doesn’t he?

Eileen: Yeah, but, you know, his dad drowned when Allen was a boy. He was a sea captain, and his ship was lost at sea. That left just Allen and an older brother, and there was a handicapped aunt that lived with them as well. So I’m sure that his mother had her hands full. She worked, too, but I know she needed help.

JM: How old would Allen have been when his father died?

Eileen: I don’t know for sure.

JM: What was his father’s name?

Eileen: Guy Carlton Chaffey. We always kind of joked about it, because my dad’s name was Guy Carlton Dougherty. He was named after Allen’s father, instead of after his real father. My father and Allen were actually half-brothers, because they had different fathers – same mother, different fathers.

JM: But they grew up together?

Eileen: Allen was about 17 when my dad was born. He was really more like a father to him.

JM: So they had a close relationship.

Eileen: Yes, and Allen was very much part of my life also. He was more like a grandfather, because he was a lot older. He and his wife Leona had no children, so they kind of treated my brother and me like grandchildren.

JM: In the caption of the photo, it says, ‘Allen, 9 years old, helps mother pack in Seacoast Canning Company.’

Eileen: She obviously had to work. Allen loved his mother, and I am sure he was happy he could help her.

JM: What do you think about Allen working there at such a young age? Is that something that is well known around Eastport now, that kids were working that young?

Eileen: Well, I guess the older people knew. But nobody thought there was anything wrong with it. I can remember that on my mum’s side, she said that when her grandmother would pack fish, she would tie her young child to the table at the fish factory so he wouldn’t wander off. So everybody just kind of accepted it. It was just something you did as a family to survive.

JM: Lewis Hine took about 50 photos in Eastport. Some are pretty disturbing. There are several kids with very badly cut fingers from cutting the fish. And some of these kids were six or seven years old. There were two kids who had a big butcher knife in their hand. And there was one of a little girl who was photographed four times. In one of them, she was running back to her house right after she had cut her thumb. It was apparently bleeding profusely, and she looked like she was screaming as she was running. Hine must have just been happening by when he saw what was going on. I don’t know whether Allen would have been subjected to similar conditions.

Eileen: Well, if he was packing fish, he would have either used knives or scissors. Since he never talked about it, I don’t know what his job was.

JM: Do you know how far he got in school?

Eileen: He went through high school. He didn’t go on, but he helped his older brother go through college. And then he helped my brother and me to go through college.

JM: What did Allen do for a living?

Eileen: As a younger adult, he worked on the Quoddy project, in Quoddy village, in Eastport. I think his job was sort of a lecturer. He would lecture on the proposal, and he was quite proud of it. Allen was very smart. And he loved figures and numbers.

JM: Was this some kind of development?

Eileen: Yes. I’m not really sure of all the details of it, but it was like military housing. He wasn’t in the military, but they hired civilians. There was an infirmary, and there were barracks and other things out there. (Note: The Quoddy Project was a 1930s federal government project to build dams in order to generate electricity. It was never completed). When I was growing up, he worked at the Western Auto. He was a shop keep. He did that for a lot of years. And he would walk to work, all the way to the other end of the island. He never owned a car. He never had a telephone either. But he had one of the first TV sets in town. When we didn’t have one, we used to go up to his house on Sundays and watch the Ed Sullivan Show and Don Messer’s Jubilee. He had a sun porch overlooking the bay, and it was really wonderful. That was his favorite perch. He sat and watched all the activity on the water, the boats and ferries. He had binoculars, and he could tell you who had been fishing and how much the catch was. He loved to hunt and fish. We’d go fishing on Sundays, and when the weather was good, we’d go haddock fishing, with hand lines. He’d take us out on a boat. We would fish until we filled a bushel basket. We’d go back, and Mum would have the onions and potatoes cooking for chowder, and we had really fresh fish chowder.

JM: Sounds good.

Eileen: It was good! We had some really happy memories in the boat. Somebody once said, ‘Gee Eileen, you must really know a lot about boats.’ And I said, ‘Well you know, it’s funny, but I don’t. Because my job was to bail and that’s all I did when we were out in the boat. I bailed the whole way out and the whole way back. Allen was very tender hearted. Like if we were fishing off the Canadian Islands, we would go behind Campobello and Indian Island, and a lot of times there would be shags or gull nests and things like that. He would always silence me and point, and I would know to look, because he had spotted something, like a baby in a nest, something very tender. He always noticed the little things in life.

JM: Did he live longer than his wife, or was it the other way around?

Eileen: He died first. He had a heart attack. Of course, he had no phone. So he had to walk to the neighbors to summon help. By the time he did that, he had extensive damage. So he didn’t survive. Back then, we didn’t have an ambulance. You would go to the hospital in the back of a Hearse and they would give you oxygen. His wife lived till six or seven years later, I think. Allen left quite a bit of money to take care of her and left about $50,000 to my brother.

JM: That’s an awful lot of money.

Eileen: I don’t know why he deprived himself. But he still enjoyed life. He had a camp. He went to the lake and did freshwater fishing, but then he sold the camp when he got older and used that money to help educate us. When he retired, he had awful bad arthritis in his knees. And, of course, he had done all that walking all his life. So it was really hard for him. But other than that, he really didn’t have any health problems.

Allen and my father owned a house on Indian Island, which is a Canadian island off Eastport. It was left to them by Allen’s brother Harold. And because Harold had no children either, when he died, my dad and Allen inherited it. And it was really great. It was a very old house, and we would go over in the summer and stay there, but Allen would not come with us. But from his porch, Allen could see the beach on Indian Island, and every night we would go down and flash the flashlight so that he knew we were alive and well, and he would flash his porch light to answer us. Of course, we didn’t have cell phones or anything like that then. So that was the only way that we could acknowledge that we were okay. Some nights, if the weather was really bad or the fog was in, and we couldn’t see, we’d always wonder if Allen knew if we were alright. I had a wonderful childhood, and Allen was a wonderful part of it.

JM: Did you also work at the canneries?

Eileen: Yes, I worked in the factories. I packed sardines.

JM: How old were you when you started?

Eileen: About 15 or 16.

JM: And were you working there all year round or just in the summer?

Eileen: Just in the summer, but it was six days a week, and you worked until the fish were gone, maybe till 8 or 9 at night. They had a bus that came around to everybody’s house and picked you up and took you to work. And they’d take you home for an hour at lunch. And they’d come pick you up and take you back to the factory. It was great. And everybody worked. I mean, all your friends were there, so it was fun.

JM: How were the working conditions?

Eileen: Well, it was wet and cold, but nobody thought about it. And you had to tape your fingers up or you’d get cut. I had a table partner. She was an old lady. She would scoop her fish, but she wouldn’t take time to drop her scissors, so she would use her hand with the scissors in it, and if I wasn’t careful she would poke me with her scissors. So I had to really be on the lookout. She got me a couple times, but nothing drastic.

JM: Was it piece work?

Eileen: Yes.

JM: So the more you put out, the more money you made.

Eileen: Yes. But I was pretty slow, so at the end of the day the old ladies would help me fill my last case by packing a couple of cans and dropping them in the tray. The older workers looked out for the younger ones.

JM: I talked to the son of one of the other kids that worked in the Eastport canneries, and he said that his father always told him that the kids competed for these jobs.

Eileen: Well, when I was there, anyone who wanted to work there could get a job, because there were quite a few factories. So there didn’t seem to be a shortage of jobs available. The boys didn’t usually pack; they worked on the machinery. The women and the girls were the ones that packed. I’m sure it was very different when Allen was there, because I think at one time there were 13 factories in the area. And there were a lot more people. It was a much bigger community. I think the children felt proud to be able to help their parents and families.

JM: Did you go to college?

Eileen: I went to nurses’ training in Bangor (Maine). When I was getting ready to go to nurses training, I needed to take a chemistry course at the high school. I was packing fish, and the factory owner let me have the time off to take the class every day, and I would go up in my fish clothes, which didn’t smell too great, and with my hands all taped. And I would take the class, and nobody said a word. I just sat there with the other kids and studied, and then when I left I went back to the fish factory. I did that for a year.

JM: When you went to nurses’ training, did you live there, or did you have to travel back and forth?

Eileen: You lived right in the hospital back in my day. I did that for three years. And my brother went to Maine Maritime Academy. Allen was very proud of him.

JM: Were you a nurse most of your life?

Eileen: I still am. I love old people and take care of them in their homes.

JM: Have you lived in the Eastport area all your life?

Eileen: I’ve never lived anywhere else. I love Eastport. I still have my parents’ home. When Allen died, his wife moved into an elderly housing complex and gave her house to my brother. And when my brother died, his widow sold the house. So somebody from away owns it now. But they fixed it up beautiful.

JM: Lewis Hine spent about 10 years, between 1908 and 1917, going around the country just taking thousands of photographs. The National Child Labor Committee had hired him. Their mission was to get child labor laws passed. At that time, there were few child labor laws in the country. When he went to Eastport, I don’t think he would have been particularly welcome, so he probably had to sneak around quietly.

Eileen: I don’t know. Eastporters would have welcomed him.

JM: But his mission was to expose child labor, and he might have been viewed as a threat. You can tell by the photos that he was seldom allowed in the canneries. He had to wait for the kids to go to work or come home from work, to take the pictures.

Eileen: Well, the factory owners wouldn’t have been happy about it. The workers themselves probably wouldn’t have minded at all; but on the other hand, if they needed that income to survive they would have been upset if he had stopped their children from working. That’s food on the table.

JM: You can correct me on this, but I think most of the kids that worked when they were real young were working mostly in the summer. Hine took the photos in August.

Eileen: Yes, it must be, because Allen went to school. I believe they had truancy laws. Like I said, Allen was very smart. I think that if we had lived in a different place with more opportunity, he probably would have gone to college. But he helped his older brother go, and Harold got his degree in English, in fact he actually got his doctorate. He actually received it after he died. He was blind and had diabetes. He had some toes amputated and what not, and my mother was a nurse. She would tend to his needs medically, and then she would read to him. And then he would tell her what to write. And so she helped him write his thesis. And then after he died, they awarded his doctorate.

JM: Where did he go to college?

Eileen: Bowdoin (in Maine). Then he taught high school English in Vermont. He didn’t come back home until he was old and sick. Well, he wasn’t that old. He died in his 60s.

JM: It’s interesting to look at Allen’s picture. Given the situation, most people would probably think that he didn’t have any chance of going very far, and yet he was pretty successful and made quite a bit of money.

Eileen: I had no idea that he had this kind of money. But he wasn’t rich. He was pretty middle class all his life. He was very frugal, almost to the point of being stingy. I mean, right down to how often you flushed the toilet, or how often you took a bath. He watched every penny. So you knew when you got a gift from Allen, it was very treasured. He worked very hard, and I think that came from this factory work and living in a poor town. All of his friends were in the same boat. Everybody was working hard, but it wasn’t a bad thing. He didn’t know any different. If he hadn’t been working as a child, he’d have been home alone with nobody to play with, because all his friends would have been working. A lot of kids don’t get that experience of work until they’re older. I live on a farm, so my kids all get to work in the hay fields. It’s their favorite time, being all together as a family. There are some dangers at times. We’ve had some farm accidents, but fortunately nothing has been too tragic.

I think Allen would want to be remembered as being very faithful. He never went to church, but he loved life and his family. And he loved nature. I think that was really what gave him happiness. It wasn’t money. He saved it, and watched it, and counted every penny, but that was not his happiness. He said grace before every meal and thanked God for his blessings. Allen always took care of others. His mother moved in with him when she got old, and he took care of her until she died. He also helped his brother, who lived next door until he died.

Allen Chaffey: 1903 – 1977

*Story published in 2009.

**************************

Walter Omar

Walter Ivory Omar was born on July 7, 1903, in Lubec, Maine, the son of Alfred Omar and Nellie (or Nettie) MacDonald. They were divorced sometime between 1910 and 1916. He married five times, the first four of which ended in divorce. He had two daughters, Antoinette (now called Helena) and Emily. He died in Nashua, New Hampshire, on July 17, 1970, at the age of 67. I obtained his obituary from the public library in Nashua, and that enabled me to find his two daughters. I interviewed one of them, Helena Frey.

Edited interview with Helena Frey (HF), daughter of Walter Omar. Conducted by Joe Manning (JM), on January 5, 2007. Transcribed by Jennifer Suh and edited by Manning.

JM: What was your father’s full name?

HF: I think his middle name was Ivory. On my birth certificate, his last name was O’Mar, but he dropped the apostrophe later. I ran into an Omar from Ireland, but it was spelled Omeagher, with no apostrophe. He said that the Omeaghers were from the poorest province in Ireland, and that they were known for being mercenaries.

JM: When were you born?

HF: I was born in Portland, Maine, on April 11, 1934.

JM: And at that time, were you living with your father?

HF: Yes.

JM: Who was your mother?

HF: Helen Johnson. Her last married name was Smith. She married three times. My father was her second marriage.

JM: At the time you were born, what was your father doing for a living?

HF: I think he was a shoe salesman.

JM: At a shoe store?

HF: No, he was on the road. He was a traveling salesman.

JM: Did you see him often, or was he always on the road?

HF: At a later point, he wasn’t on the road. He was also a professional welder. And then during the war (WWII), I did not see him as much. He worked for the oil companies in Arabia. We stayed with my grandmother in Bath (Maine), and my mother went to work as a secretary in Washington, DC.

JM: Did he manage to get home occasionally?

HF: Not at that particular time period. Finally, we reconnected. We left Maine and rejoined him in Hawaii.

JM: How long did you live in Hawaii?

HF: For a year.

JM: What was your father doing there?

HF: He was teaching welding.

JM: How did he learn welding?

HF: I don’t know, but he became very good at it. I guess the opportunity opened up and he got the training he needed.

JM: When did your mother and father divorce?

HF: About 1947, when I was 13 years old.

JM: Were you close to your father then?

HF: Well, as close as one could get to my father. You know, my father could have been an Arnold Palmer. He was so good at golf, so good at sports. He was good at bridge and poker, but he couldn’t help himself. He didn’t like winning without getting it over somebody. He was very competitive. Instead of being a professional with golf, and just playing a really good game and getting into professional competitions, he really liked to be sort of a con man.

JM: After the divorce, did you remain close to your father?

HF: Not really. We would write every once in a while.

JM: When did he move to New Hampshire?

HF: Toward the end of his life. He first went back to Belfast (Maine), where his mother and his stepfather had a bed and breakfast. His mother had married very well the second time. In the 1930s, she went to South Africa to sell Singer sewing machines. She met someone there who owned a Johannesburg goldmine. She married him and they came to the United States to start up the bed and breakfast.

JM: What did he do when he went back to Belfast?

HF: I think he set up a billiard parlor, something like that. He was also an auctioneer. He had a warehouse full of things that he would auction. He would go around and find things and get involved with people who were closing their estates.

JM: It sounds to me like he was really resourceful.

HF: Yes, he was.

JM: His resourcefulness may have come from working in the cannery as a kid. I talked to one woman whose father worked at the cannery. He got only as far as the fourth grade, but he became the owner of a gas station, and eventually turned his gas station into a convenience store. His daughter, who’s a school librarian, said that her father was the smartest man she ever knew. He actually helped her with her algebra once, even though he wouldn’t have known anything about it. She said that when he worked at the cannery as a child, he did piece work. So the more work he did, the more he got paid. She thinks that helped him learn how to get ahead in life.

HF: On the other hand, my father was unbelievably bright and capable, but unable to pass it on to anyone else. He was very selfish. There was one time that he tried to teach me how to dive. And when I didn’t do it right immediately, he took me home and went off to play golf. So he wasn’t the type of person who would sit down with me and help me with my algebra, though he was probably quite capable of doing that.

JM: Did he have a good sense of humor?

HF: He carried it around with him, because he was a salesman. He knew the punch lines to 500 jokes. But that doesn’t necessarily mean he had a good sense of humor.

JM: How many times was he married? I have found records for five.

HF: I thought there might have been a marriage prior to my mother’s. And after my mother, I knew of two more marriages.

JM: You said his mother’s second marriage was to a wealthy man. But it sure looks like his mother wasn’t wealthy when your father was a boy.

HF: Heck, no. But he never let me or my mother know he grew up poor. If she had known that he had worked so young at the cannery, it probably would have made her more compassionate toward him. But instead, he said he was the son of a very wealthy woman. That was the persona that he wished to show. When we went to Hawaii, he was with a very wealthy crowd. He would go fishing on the yachts, or up to the mountains and hunt ram. He was that kind of man, like Ernest Hemingway, without the literary part. He was a man’s man, very comfortable with men, and very attracted to women, too.

JM: Were you surprised that anyone would work at a sardine cannery at that age? Or did you assume that it was just something that happened back then?

HF: I was aware of it. We’ve all seen photos like these, of the poor, like that marvelous one by Dorothea Lange. I’ve seen those photographs, but they didn’t have anything in it that I identified with personally in my family. I was very sympathetic, but until I saw my father’s picture, I thought that it wasn’t something that happened to my family.

JM: Did the boy in the picture look like your father?

HF: Well, he looks like my son.

JM: Have you shown the picture to your son?

HF: I showed it to all my children, three sons and a daughter.

JM: Did any of them know your father?

HF: Yes. My father came out to see my family in Detroit, where we lived on two occasions.

JM: What did your children think?

HF: They were stunned and excited that such a thing had been found.

JM: The caption says he was a fish cutter. He probably cut the fish with a large butcher knife. There were a lot of photos Hine took of kids with cut fingers. Do you remember if your father had any injuries to his hands?

HF: I don’t think he did. He was so skilled. He was into archery. He was in the 1939 World’s Fair competition for archery, and he finished in second place. My father was a daredevil. He jumped on a motorcycle once, though he had never been on one, started it up and sped off, not knowing how to flip on the brakes.

JM: How far did he get in school?

HF: I don’t know, but he could read and write.

JM: When your father died in 1970, had you seen him much recently?

HF: When I was living in Detroit, he came to visit me twice. He had invited me to visit him, because he was going to make out a will, and he wanted to put me in it. We finally got to Maine at one point. In the ‘60s, we went to New Hampshire and visited him.

JM: Was he married then?

HF: Yes, to Grace.

JM: Was that the last time you saw him?

HF: No. He and Grace came out to Detroit.

JM: In the last part of his life, was he the same person, or had he changed?

HF: He got emphysema. He was coughing all the time, so he was in bad shape.

JM: So do you look at your father differently, now that you have seen him at the cannery?

HF: Since I saw the Lewis Hine photo, I’ve gotten more sympathetic towards him, and I think I understand why he behaved the way he did, and why he didn’t share his past with me. I think that sometimes we don’t recognize that people feel shame about things they don’t want anyone to know about. So you get people like my father, this tremendously self-sufficient, very abrasive man, very determined. He made such a mistake. He had all this talent, and he let himself just wait around to inherit his mother’s money. The reason he married my mother was to impress his mother, so that he would be sure to get the money. And that is such a tragedy. And maybe I feel that way about him now because of your research, knowing now that he was so poor when he was a child.

I was very disgusted with my father. He committed suicide. That seemed such an awful thing to do. He finally came into a lot of money when his mother died, although there was a caveat to that. His stepfather’s family in South Africa hired a lawyer, because his stepfather had children, too, and they had a right to some of the money. If his stepfather had left it all to his wife – my father’s mother – they couldn’t touch it. That was hers. But once she left it all to her son, then the family in South Africa could claim some of it. The lawyer won the case, and when that happened, my father had already spent most of his share. That was his underpinning. And so he did what Hemingway did (Hemingway took his life), to the extent that Hemingway said, ‘It’s not fun anymore.’ So maybe my dad said the same thing. But now I see that he came out of a situation where he faced poverty, and that he just couldn’t face it again.

Walter Omar: 1903 – 1970

*Story published in 2009.