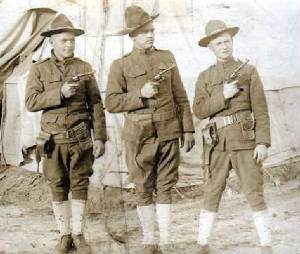

Lewis Hine caption: Springstein Mills, Chester, S.C. Archie Love. Said (after hesitating) “I am 14 years old.” Doesn’t look it. Been in mill 3 years. Worked 5 months nights at the start. Location: Chester, South Carolina, November 1908.

“I have this picture of Daddy. It’s been in the household since I was a kid. Daddy told me that he was going to work when the picture was taken. I don’t remember Daddy ever saying where it came from. It’s 5×7, on glossy photo paper. Although it is old and has been handled a lot, it’s still in pretty good shape. It could be an original.” -Paul Love, Archie Love’s son

In Child Labor in the Carolinas: Account of Investigations Made in the Cotton Mills of North and South Carolina, by Rev. A. E. Seddon, A. H. Ulm and Lewis W. Hine, Hine said of the textile mills in South Carolina: “In general, I found these were considerably worse than conditions in North Carolina, both as to the age and number of small children employed. In Chester, South Carolina, an overseer told me frankly that manufacturers in all the South evaded the child labor laws by letting youngsters who are under age help older brothers and sisters. The names of the younger ones do not appear on the company books and the pay goes to the older child who is above twelve.”

This photo is typical of Lewis Hine’s best work. His respect for the child is evident here. The apparent mill housing in the background is barely noticeable, the camera clearly focusing on the boy. Archie’s handsome face is perfectly lit, and he looks comfortable in his role as the photographer’s subject. Hine wants us to believe that this boy could be one of our children, not some pitiful waif with whom the outside observer might not empathize.

It didn’t take long to find Archie’s death record. Thanks to Tally Johnson of the Chester Public Library, I obtained an obituary, and subsequently managed to locate and contact two sons, both in South Carolina. One of them, Neil Love, was completely unaware of the photo, but the other, Paul Love, had seen it.

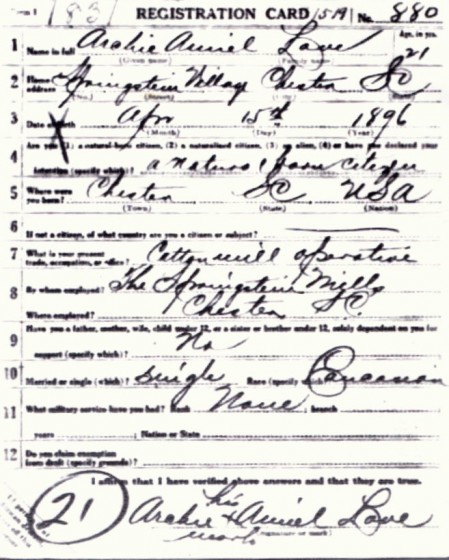

Archie Ariel Love was born November 15, 1894, in Chester, South Carolina. His father was Charles A. Love, who was born in 1869, and died in 1900. His mother was Rebecca Hoag, who was born in 1872, and died in 1946. After Charles died, she married Henry A. Thompson, and he died in 1943.

Archie had three siblings: Minnie (born 1892), Mary (1897) and Charles C. (1899). He joined the Army in 1918, and was stationed at Camp Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina. It’s now called Fort Jackson. He was discharged in 1920. He married Alice I. Adkins on Christmas Day, 1920, in the ARP (Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church) in Chester.

Archie and Alice had the following children:

Hattie, born 1922, died 1923

Rachel, born 1924, died 2003

Bobby, born 1928, died 1970

Neil, born 1930, still living

Unnamed twins, born 1932, died a few minutes later

Paul, born 1934, still living

Gene, born 1939, still living

Donnie, born 1944, still living

Excerpts from my email interview with Archie’s son, Paul Love:

“My (paternal) grandparents worked at a textile mill in Chester, where working conditions were not the best. My grandmother was allowed to take the four kids to work with her. She would put the two younger ones (Mary and Charles) in a large roll-around cart with sides. Archie and Minnie worked. Every once in a while, my grandmother would go check on Mary and Charles and nurse them.”

“The mill was not paying Archie and Minnie. They had to help their mother, because she could not keep the job up. Some of the boss men were really mean to the kids working there. They would jerk them around and hit them, and holler and curse at them.”

“Minnie went to work there when she was seven years old, and Archie, when he was eight. One time, Archie’s mother saw one of the boss men hit him, so she got a knife and chased him to the top of the hill, about five or six blocks away, where the police saw her and took the knife away.”

“I remember Daddy telling me he earned 50 cents a day when he was a kid. Later he earned $3.00 per week, but there were long hours involved, and you didn’t get lunch breaks, you had to eat while you worked, and if you had to go to the water house (toilet), someone had to keep your job running. If they didn’t like you and wanted to fire you, they didn’t really need a reason, they would just tell you that they didn’t need you anymore and that was it. That’s why most of the employees worked double hard. Times were bad, and you just couldn’t be without a job.”

“Archie worked in textiles a number of years. Later he got a couple of trucks and helped cut the right of way for the state, hauling telephone poles. He also once owned a small café and grocery store.”

“My daddy only had a third-grade education, but he had more common sense than anyone, and he had a loving and compassionate heart that was beyond belief. He died poor and broke, because he couldn’t say no; he couldn’t stand to see a person in need and doing without. In my file cabinet, I have mortgage records dating back to the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s, that Daddy held on people, that he wouldn’t foreclose on. All you had to do was just give him a little sob story, look sad and promise to pay him back, and he would fall for it.”

“Daddy worked for a man that owned a few liquor stores. They passed a state law that one person could not have over one or two stores, so he sold the store to Daddy on credit, because Daddy’s word was good as gold. We had to do without a lot, because most of the money went to pay the store off. That’s when Daddy started loaning money and co-signing bank notes for people. He ran the store a few years, and in 1955, he decided to get out of the liquor business.”

“He sold out and opened a furniture store. That was the beginning of his downfall. I saw him furnish a complete house of furniture for a family who made only two or three payments, and then they left town with the furniture. They came back to town a few years later, went to Daddy’s store, told him a bunch of lies, and he furnished another house for them. After a couple payments, they were gone again.”

“He carried the first Philco refrigerator with a V-shaped handle. It could be opened from the right or left. It sold for over $600. Daddy let this man have it for $40 down. The man made one $10 payment, then never paid anymore.”

“The house we moved to in 1941 had a porch that went across the front and down the left side. It was about eight or ten feet out. The front steps were eight or ten feet wide, and about seven or eight steps high. We did not have power tools; we only had hammers, a hand saw, a brace and bit for drilling holes, and a hand plane for smoothing lumber. At times Daddy would get someone to watch his store, and he would come home. With my older two brothers and me, we replaced the tongue and groove flooring that had rotted out, rebuilt the steps, constructed screen doors, and made screens for the windows.”

“He knew the man that owned a wholesale business in Chester. He called him and got it fixed up for us to buy boxes of candy at wholesale prices. He could have given us 80 cents and not even missed it, but instead he loaned us the 80 cents to buy the first box of candy, and he forbid us to eat any of it. A 24-bar box at five cents a bar brought back $1.20. We would buy another box and sell it and make 40 cents more, so we finally made enough to go into business for ourselves. We had to give him back the 80 cents that he loaned us. Now we could eat a bar once in a while if we wanted to.”

“I worked in a department store three hours a day, four days a week, after school, and eight hours on Saturday. I earned $10 a week and had to give Mama $5.00 room and board. I didn’t really like doing it, but Daddy was teaching me a valuable lesson, to earn my own way and not to expect a free living. My parents were both just good down-to-earth people. When I was growing up, we were not just sent to church, we were taken to church.”

“I got married in 1961 and moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, about 50 miles from Chester. We would come home every Sunday to see our families. One time, I was driving an old 1951 Chevy. We broke down just as we came through Pineville, about 10 miles out of Charlotte. Everything was closed. I walked to a closed service station and used the outside pay phone and called my Daddy and told him how the car was acting. He said he would be there soon.”

“Daddy called the man at home that owned the junk yard, and he told my daddy to go on and he would meet him there. Daddy met the man a few minutes later and found the parts we needed, loaded up his tools and a couple cement blocks, and brought them to where we were stranded.”

“Daddy was a big man, and he was somewhat crippled. He couldn’t get up and down too good. I jacked the car up and put the cement blocks under the wheels. My wife stood under a shade tree. My daddy sat on the passenger side with the door open and his feet on the ground and shouted instructions to me on what to do. A short time later, it was fixed.”

“Once something happened to one of the lights in their house. My brother and I thought we could fix it, so we went up in the attic, where the electrical boxes were, and went to work. We made the biggest mess you could imagine. You would turn the light switch on in one room, and the light in another room would come on. You could turn on another switch, and the doorbell would ring. We called Daddy, and he came home and put his chair just inside the closet. That’s where the opening was to the attic. He sent us back up there, and he sat right in that chair and directed our every move, without seeing what we were doing. When we finished, everything worked just fine.”

“Daddy could not stand a liar or a thief. When I was about 11 or 12, he whipped me one night for my continual lying about where I had been. He whipped me five times. Every time I would tell another lie, he would whip me again. After the fifth time and I told him the truth, he put the belt down and shook his finger at me and said, ‘Don’t lie to me again.’ I had a bad habit of slipping off and going down to the rail yard and hitching rides on the slow moving freight cars. Another time, he whipped me for stealing an old quarter from his coin collection and spending it. He gave me a quarter to take back to the store and get his old quarter back, and when I got back home with it, he whipped me again. Back then, I called him every name I could think of (under my breath, of course). I’ll soon be 73 years old, and I still appreciate the values he instilled in me back then.”

“My Daddy was a wonderful man. He was gullible, and too good for his own good, but I’m proud to say he was my father, and I find comfort in knowing where he and my mother are right now, and knowing I will see them again someday.”

Archie Love died in Chester on October 2, 1973. He was 78 years old. His wife Alice died five years later.

*Story published in 2007.