Whatever Happened To Arthur Albicker, the boy who was injured?

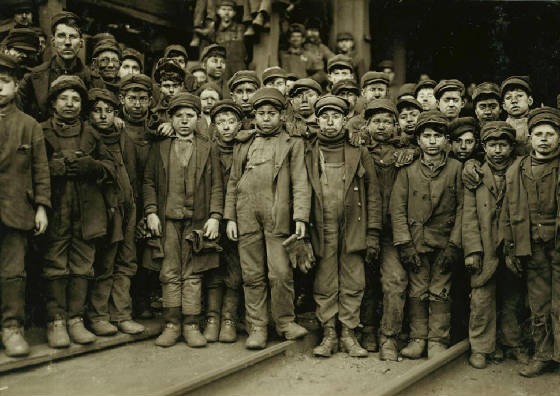

According to National Child Labor Committee Investigation Report 480, housed at the Library of Congress, and reprinted in Child Labor: An American History, by Hugh H. Hindman, Lewis Hine wrote the following after observing the “breaker boys” in the coal mines of Pennsylvania.

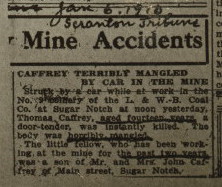

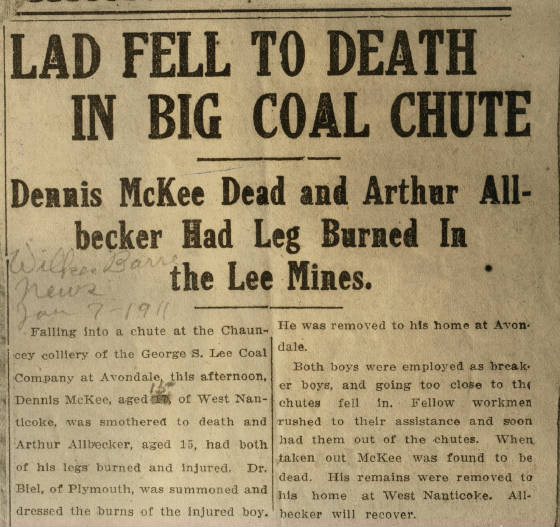

“The boys working in the breaker are bent double, with little chance to relax; the air at times is dense with coal-dust, which penetrates so far into the passages of the lungs that for long periods after the boy leaves the breaker, he continues to cough up the black coal dust. Fingers are calloused and cut by the coal and slate, the noise and monotony are deadening; and, worse still grave danger from the machinery to those boys who persist in playing about the breaker, and even for those at their regular work. While I was in the region, two breaker boys of 15 years, while at work assigned to them, fell or were carried by the coal down into the car below. One was badly burned and the other was smothered to death. This was at the Lee Breaker at Chauncy, Pennsylvania, January 6, 1911; the boy who was killed was Dennis McKee. The coroner told me that this boy had reached his 15th birthday only a few days before his death and the evidence seems to prove that he was working in another breaker before he was 14 years old.”

Lewis Hine caption: A view of the Pennsylvania Breaker. The dust was so dense at times as to obscure the view. This dust penetrates the utmost recess of the boy’s lungs. Location: South Pittston, Pennsylvania, January 1911, Lewis Hine.

Lewis Hine caption: Breaker of the Chauncy (Pa.) Colliery, where a 15 year old breaker-boy was smothered to death and another badly burned, Jan. 7, 1911. (Photo of newspaper clipping #1946.) The Coroner told me that the McKee boy was but a few days past his 15th birthday when he was killed, and that the evidence seemed to show that he was at work in another breaker before his 14th birthday. (He will report to us on that point, further.) Location: Chauncy, Pennsylvania.

In some of his most wrenching photographs, Lewis Hine showed us the “slate pickers,” also called “breaker boys,” who worked in coal mines. The best known of these were taken in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania. At that time, there were laws on the books that restricted the working age of miners. Breaker boys had to be at least 12 years old. Despite the age restrictions, poverty-stricken parents often presented phony birth certificates, so that their children, as young as five or six, could earn money for the family. The coal companies wouldn’t have cared less that these diminutive boys were obviously under age.

Hine traveled though Luzerne County in January of 1911, visiting coal towns such as Pittston and Nanticoke. On January 6, there was a serious accident which took the life of young miner Dennis McKee, and injured another youngster, Arthur Albicker. Hine saw an article about it in the Wilkes-Barre News, and sent the clipping to the National Child Labor Committee, the agency he was working for. I saw an image of the article on the Library of Congress website in October of 2007, and I immediately wondered what happened to Arthur, who suffered serious burns to both of his legs. Did he recover, as the article predicted? Did he return later to the mine?

I looked in the 1900 census and found Arthur, born about 1895, living in the Luzerne County town of Hazle, with his parents, Emil and Martha Albicker (not Allbecker as the article stated) and five siblings. Emil, who emigrated from Germany in 1884, was employed as a stable boss in a coal mine. According to several sources, a stable boss supervised coal miners who cared for horses and mules that worked inside and outside of the coal mine. In 1910, the year before the accident, Arthur was a 14-year-old slate picker, and his father was a coal breaker. This time, the family was living in the town of Plymouth, also in Luzerne County.

It appears that Arthur substantially recovered. According to Luzerne County military records, Arthur served with the 109th Field Artillery Battalion during World War I. And in the 1920 census, he was still working in the mine, but listed only as “laborer.” He was living with his parents in Plymouth, and his father was listed as a house carpenter. Then I ran out of luck. There are no further records of Arthur, not in the 1930 census, not anywhere. In fact, there are no Albickers in the 1930 census in Pennsylvania, and none with a similar name in Luzerne County. The census taker probably missed them.

After a few frustrating attempts, I finally unearthed some scraps of information, which led me to several descendants who knew almost nothing about Arthur. I found the death record and obituary for a Leo Albicker Jr, the grandson of one of Arthur’s sisters. He died in Alaska in 1998. I found the phone number of one of Leo’s surviving sons (he also lives in Alaska), and gave him a call. He had never heard of Arthur. He told me that his father and grandfather had been living in Alaska since the 1930s, and that he hadn’t visited relatives in Pennsylvania since the 1950s. I sent him a copy of the article.

In desperation, I asked the Wilkes-Barre Times-Leader to publish an article about my search to see if any readers knew anything about Arthur. They suggested a short letter to the editor, so I sent it in. I kept checking online to see if they had run it yet, but several weeks went by, and I couldn’t find it. So I tried looking for the letter by searching their archives for “Albicker,” and came up not the letter, but a surprise: a 2007 obituary for a woman who was the daughter of one of Arthur’s older brothers. She died in Nanticoke. A couple of phone calls later, I was talking to one of her surviving sisters.

She knew nothing about the accident in 1911. She told me that she was born in 1930, and that her uncle Arthur died when she was very young, perhaps in the early 1930s. She didn’t know whether he was still working in the mine then, whether he was married, what caused his death, or where he is buried. All she remembered was that he was living in Luzerne County when he died.

I called several of the oldest funeral homes in the area. One of the directors recognized the Albicker name, but had never heard of Arthur. When I asked if he had records back to the 1930s, he said, “We did at one time, but all of them were lost in the flood.” Unfortunately, access to official Pennsylvania death records is limited to persons who can verify that they are close relatives, and even then, a request has to be accompanied by the date of death.

According to a list on the Web of deaths of prominent Luzerne County citizens, George F. Lee, the owner of the coal mine where Arthur was injured, died on February 22, 1946, at the age of about 73. But whatever happened to Arthur Albicker?

Epilogue

On April 5, 2008, about a week after I posted this story, my letter to the Wilkes-Barre Times-Leader was finally published. A few hours later I received an astonishing email:

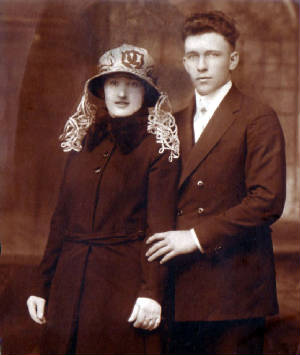

“My name is Lori Bates. Arthur Albicker’s mother, Martha McAfee Albicker, was my great-grandmother. My grandmother was Elizabeth Rossman. Martha and Emil Albicker raised her after her father was killed in an accident when she was a baby. Martha and Emil then had six children: Ellie, Edward, Arthur, Hugh, James and William. Arthur recovered from his injury at the mine. He married Louise, and they purchased their first home in Plymouth. They were about to have a daughter when he died in 1931. My grandmother Elizabeth always said that Arthur was her favorite (half) brother.”

I replied right away, and after several subsequent email exchanges, I had a photo of Arthur and his wife on their wedding day, several other photos, and more of the story.

When he served in World War I, Arthur suffered serious exposure to mustard gas, and it permanently damaged his lungs. When he returned, he received a disability pension and never returned to work. He married Louise soon after the war. Their only child, Lorraine, was born right after Arthur died in 1931. Lorraine never married, nor did she have any children. Sadly, she died of leukemia when she was only in her mid-twenties. Arthur was buried at St. Francis Cemetery in Nanticoke, PA.

*Story published in 2008.

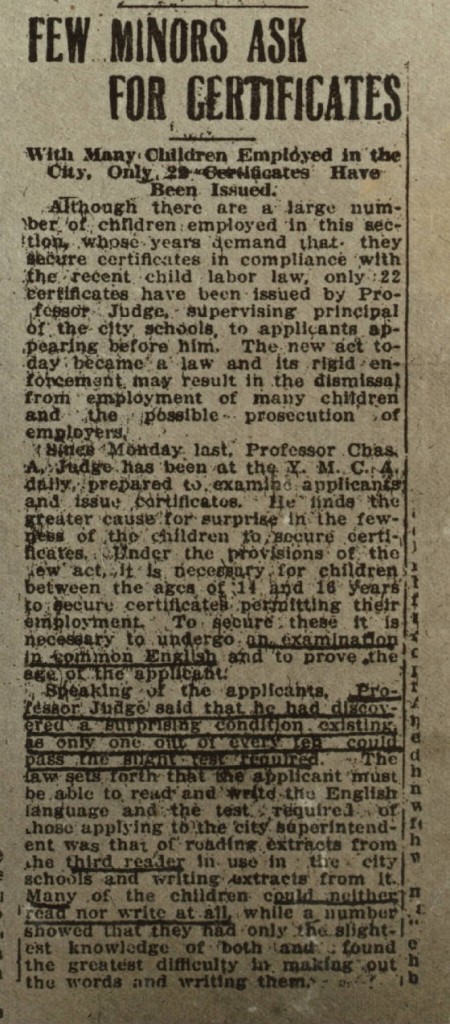

Below are is another of Lewis Hine’s famous “breaker boy” photos, and some 1910 newspaper articles about the enactment of child labor laws in Pennsylvania exactly a year before Arthur Albicker’s accident.

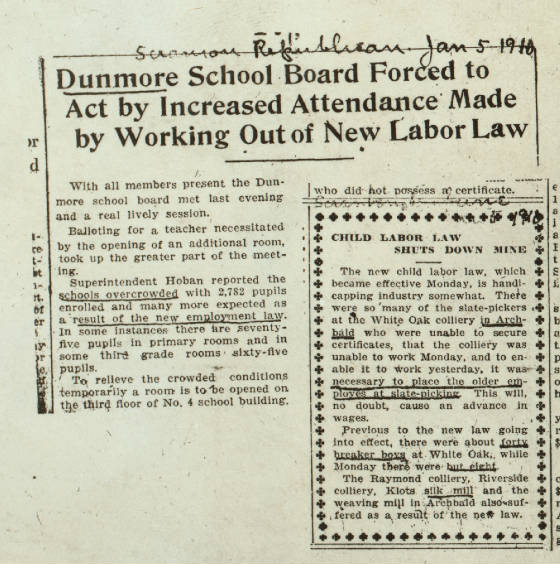

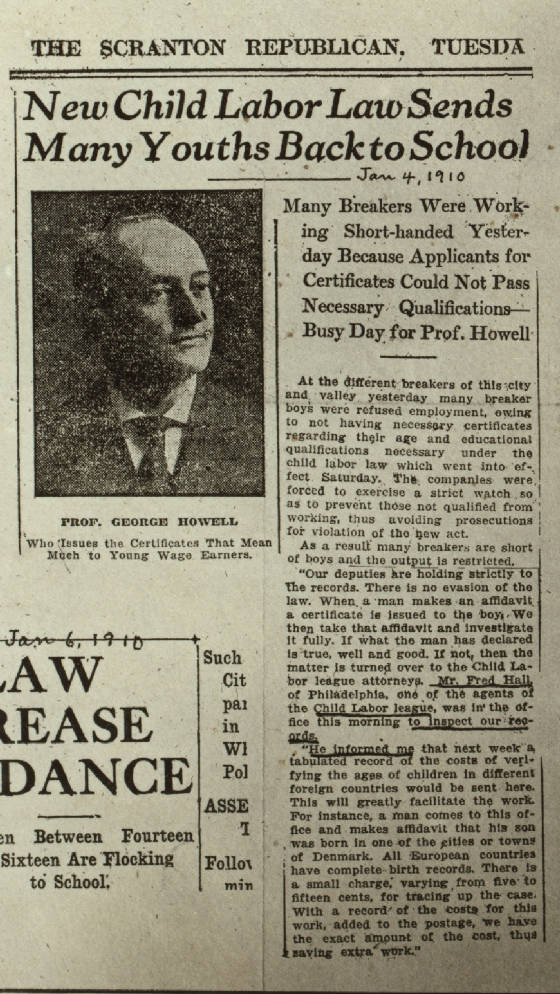

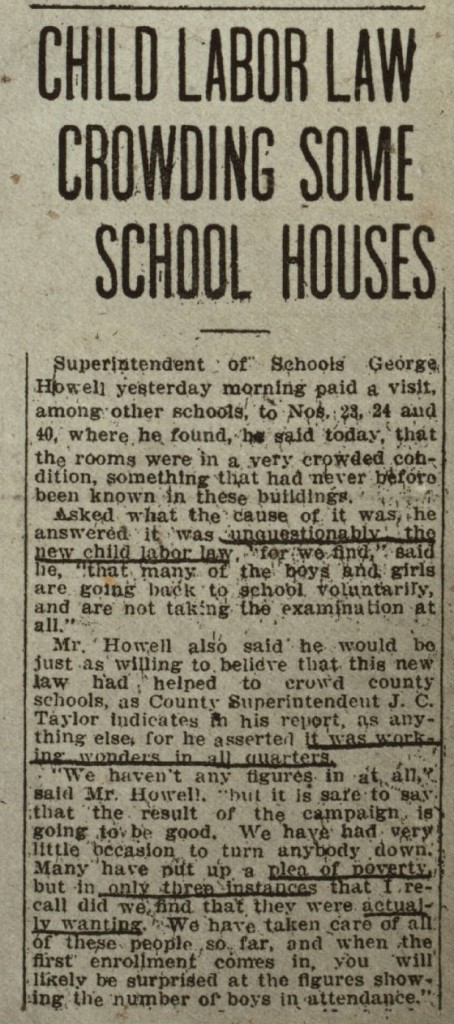

The following collection of articles (and one headline) were published together in January 1910, and sent to the National Child Labor Committee by Lewis Hine. Below is the full page, and the five full articles.