Lewis Hine caption: Arthur Chalifoux, 3 Rand St. (4th boy from left). Works in Eclipse Mills, No. Adams. Location: North Adams, Massachusetts, 1911.

“Three girls fainted in the Eclipse mill yesterday as a result of the extreme heat. The long continued hot spell is beginning to tell on all classes and there will be general rejoicing when it ends.” –North Adams Transcript, July 6, 1911

Lewis Hine visited North Adams in the last week of August 1911. He was in neighboring Adams on August 29 and 30, and then headed for Winchendon, Mass. The Chalifoux family might have taken note of the two front page stories in the North Adams Transcript, which appeared earlier that month. Certainly, everyone would have been talking about it.

According to the articles, the Hoosac Mills Corporation, owners of the Eclipse Mill, where young Arthur worked, and the nearby Beaver Mill, where Arthur’s half-brother, Thomas Chalifoux, was an engineer, announced plans for a million dollar addition to the Eclipse. To help finance their plans, the company intended to abandon the Beaver Mill, removing its machinery and equipment to the new Eclipse plant. This may explain why the following year’s city directory listed Thomas’s employer as the local Richmond Hotel. He was probably laid off from the Beaver.

Arthur had turned 14 years old about a week before Hine photographed him, making him a legal employee for the first time, according to the Massachusetts child labor law. It is likely that he started working in the mill several years before, since the family recalls him stating many times that he had to quit school at a very young age in order go to work full time.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Arthur’s neighborhood was almost entirely populated by first and second-generation French-Canadian immigrants. Most adults spoke French at home, while their children quickly picked up English in school or on the street.

Arthur was born in North Adams on August 19, 1897, to Theophile Chalifoux and his second wife, Rose De Lima Leclerc. They had been married in Quebec in 1893, after Theophile’s first wife, Rose De Lima Lecuyer passed away. The first marriage had produced a son, Maximillien Thomas Chalifoux, born in 1874. He was known commonly as Thomas.

In 1901, Theophile’s second wife died, leaving Arthur (only four years old) and two siblings without their mother. She was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave in St. Joseph’s Cemetery in North Adams. Arthur moved in with his half-brother Thomas, who was 23 years his senior. Theophile married for a third time later that year, to Elmire Faille. He would have been about 54 years old at the time.

Arthur lived with Thomas at 319 Beaver Street, one of a row of small apartments near the Beaver Mill. In 1911, they moved to 3 Rand Street, a two-story house which was likely a duplex. Both places are still standing. The Beaver Street apartment house appears unchanged, but the Rand Street house is now a single-family residence, and has been renumbered 45 Rand St. It is about a half a mile from downtown, and is just off Union Street, which is Route 2 (also called the Mohawk Trail).

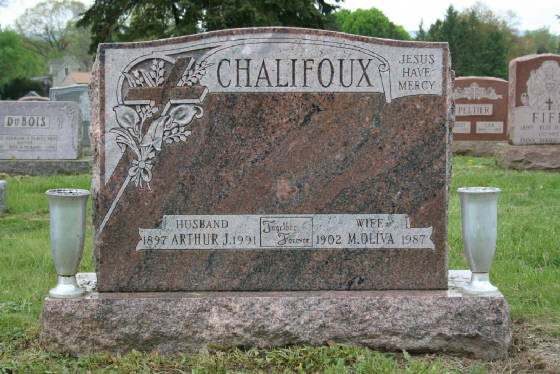

It is not known what kind of relationship Arthur had with his absent father, but a 1906 article in the North Adams Transcript states that Theophile was sentenced to 60 days in prison for not paying child support. Around 1915, Thomas and family moved to Holyoke, Mass, widely known as a center of the paper industry, which provided career jobs for both Thomas and Arthur. In 1922, Arthur married Oliva Ladouceur. They had three children. Arthur’s father, Theophile, died in Quebec in 1937, at the age of 90. It is not known if Arthur ever saw him after he moved to Holyoke. Thomas lived to be 97 years old. Arthur died in 1991, at the age of 93. His wife, Oliva, died in 1987, at the age of 84.

Through a series of death records and obituaries, I found one of Arthur’s grandsons, David Cronkright, who lives in South Hadley, Massachusetts. I interviewed him.

From the North Adams Transcript, December 30, 1911:

On Monday, the first day of the New Year, the new 54 hour law for women and children in factories will go into effect, and the schedules in the mills and factories are today being adapted to new conditions. There is no uniformity in the method of cutting off two hours from the present schedule. Each establishment has worked out its own ideas.

“This law operates so that the decrease in working hours is accompanied by a corresponding decrease in pay. Those who are working by the hour lose two hours’ pay. Those who are working on piece work two hours less a week than they have been doing consequently earn less,” said a prominent mill owner this afternoon.

At Arnold Print Works, the hours for women and minors have been arranged from 7 to 12, and 1 to 6, five days a week, and from 7 to 11 on Saturdays. At the Windsor Print Works, the Blackinton mill, the Clark Biscuit factory, the Eclipse Mill and the Hoosac Worsted mill, each day of the week is to be made proportionately shorter.

Edited interview with David Cronkright (DC), grandson of Arthur Chalifoux, conducted by Joe Manning (JM), on May 31, 2008.

JM: Tell me about your grandfather.

DC: He was my mother’s father. My mother’s name was Claire. She was born in 1933, and passed away 10 years ago. I was born in 1953. My grandfather also had a son, Raymond, and another daughter, Doris. She passed away at seven years old of spinal meningitis.

JM: Where was your grandfather living when your mother was born?

DC: On 168 West Street, in Holyoke.

JM: Did he own his house?

DC: No, he always rented.

JM: Where did he work?

DC: Marvellum Paper Company, in Holyoke. He worked there 35 years.

JM: What did he do in his job?

DC: I don’t know, but I know the company made wrapping paper, because he used to bring some home.

JM: When did your grandfather pass away?

DC: In 1991, when I was 38 years old. He was 93.

JM: Did he live close by when you were growing up?

DC: We lived at 438, and he lived at 433, five doors away from each other. I saw him just about every day. After my grandmother passed away, we would have him over for supper every night, so he wouldn’t have to cook.

JM: What kind of relationship did you have with him at that time?

DC: I was always talking to him. He liked to talk about the old days, about how kids are today and what had changed, how hard the times were, going through the Depression. He talked about losing his daughter. He talked about carrying her to the doctor from his house all the way to High Street, because they didn’t have a car. It just about killed him when Doris died. He kept her picture in his wallet all his life.

JM: Did he ever mention North Adams?

DC: All the time, sometimes about working in a factory, but not at the young age he was in the picture. He said he walked a mile and a half to school. He talked about sliding (sledding) down the Mohawk Trail (Route 2). He loved it there. He had a nephew that lived up that way. We’d take a ride up there with him to see his nephew, and sometimes spend a week there and help him with the garden.

JM: When you went to North Adams, did he ever show you where he lived?

DC: He showed us around the area, mostly the Williamstown area, where his nephew lived. But when we drove through North Adams, he would always say that he was born and grew up there.

JM: I have his World War I draft registration here, from 1918, and it lists his address as Holyoke.

DC: Oh my gosh, that’s his signature. I can tell. That is amazing.

JM: It says here, ‘two finger of left hand injured.’

DC: That also amazing. That finger was always sticking up. He said it was an injury, but he never told me what caused it.

JM: And here he is in the 1910 census.

DC: His brother Eugene is listed. He said that Eugene was his real brother, and that he had some half-brothers. He was very close to Eugene. (Note: Eugene was half-brother Thomas’s son. He was born in 1902, the year after Arthur started living with Thomas).

JM: How old was he when he retired?

DC: When he left Marvellum, he went right back to work. He did some office cleaning jobs, and finally stopped working when he was about 65.

JM: Did your grandmother work?

DC: Yes. She worked as a cook for the Lestoil Company, in Holyoke. She also worked for a doctor as a nanny and housekeeper.

JM: What did his son Raymond do?

DC: He was in the Marines. He got a back injury that was a service-connected disability.

JM: What did your mother do?

DC: She was a nurse’s aide, and she worked in a paper mill. She had many kinds of jobs.

JM: Did your grandfather ever talk about his French-Canadian ancestry?

DC: My grandparents went to Montreal a lot. My grandmother had a sister up there, and they would stay with her. Both of them were Catholic. They were married at Immaculate Conception in Holyoke (historically the French-Canadian church).

JM: What did you think of the photo?

DC: I loved it. It fascinated me, seeing my grandfather as a little boy.

JM: The photo was taken to convince people that children shouldn’t be working at that age. What do you think your grandfather would have thought about that?

DC: I think he would have agreed. When you listened to him talk, you actually felt pain about the way he struggled all of his life, from the time he was a little boy. My grandparents never had anything. He said he made $25.00 a week when they were raising three kids. When he left the paper mill, his pension was $25.00 a month. When they died, they had insurance policies that were enough to bury them and almost no money to split between my mother and her brother. The only possessions they left were their furniture and stuff like that. He always seemed like he thought he was nobody, that he never achieved anything in life. But he had a lot to offer.

He was like a father to me. My mom got married when she was 16 years old, and she was divorced when I was less than two years old. So when my mom was working, my grandparents would take care of us children. After school, we would go to Grandma’s. We were really close. Then my mom remarried, but my grandparents took us a lot of places, like to Lake Champlain, where they rented cabins, and we would stay with them as long as a month.

He used to say that when he was young, he really worked hard. He would always say: ‘You people have it easy today. You don’t know what I went through as a little boy. You don’t know how lucky you are. You’ve got everything; it’s all handed to you. I didn’t have that.’ I look today at my life, and it’s not easy. I struggle day to day, but I’m comfortable. I look back at him and know that he had it worse, so I’ve learned from him to be happy with what I have.

He loved to fish. Right up to when he died, he would go fishing in the Deerfield River, up on the Mohawk Trail. My grandmother died in 1987. Even after that, he did a lot of things. He was still driving when he was 90. And then he started having trouble with his eyes, so he just said, ‘Here’s my keys, I’m done driving.’ He was gardening right up until he died. He went berry picking, and he would do this all by himself. When he was in his late 80s, he was featured on a local TV news program as the oldest active bowler in the area.

He told us he had to leave school and go to work, but didn’t tell us at what age that happened. He probably didn’t think he would amount to anything, but the picture shows that he was an important part of history. If he was alive today and saw this picture, he would be tickled. If you had visited him to talk about this, you would never have been able to get away. He had story after story.

I am a grandfather, and I wish I could be the grandfather to my grandchildren that he was to us. It was a real blow to me when he died. I saw him that morning waving at me through the window, and then I got a call at work that he was gone. He was a fantastic man. We loved him dearly.

*Story published in 2010.