Lewis Hine caption: Three young cutters who work in the Seacoast Canning Co., Factory #4, Eastport, Me. They work at night when the rush is on. Youngest is Rob Collins, 10 years old; next is Dan Collins, 11 years; next is Milton Shannon. All live on South Clark Street. Location: Eastport, Maine, August 1911. (Note: Boy identified as Rob Collins was Daniel’s first cousin. According to Daniel’s son, his father is the boy on the right, and Rob is the boy in the middle).

“Both my mother and father worked. They put in long hours. My mother packed fish. In the wintertime, she took care of three kids for a woman who was working. We weren’t rich, but I had a good childhood. They didn’t owe any money when they died.” -Daniel Collins, Jr., son of Daniel Collins

The following is from The Fisherman, Volumes 1-2, Gloucester Fishermen’s Institute, Gloucester, Mass, 1895.

“Nearly every coast town of any size in Eastern Maine has one or more sardine factories, there being eighteen in Eastport, which furnish employment to a great many hands that would otherwise be idle, or to those who are too young or unfit to engage in more difficult work, but to whom the need is great. Many different ages are represented, working side by side at the long tables where the fish are cut or at the packing benches. At one factory, I saw a woman of seventy working more nimbly than her granddaughter of ten beside her.”

“The work is not so unpleasant as one might at first suppose in consideration of the combination of fish and oil, but the rejected parts of the herring are speedily carted away to be sold for fertilizing purposes, and in a well-regulated factory a pair of scrubbers are kept constantly employed making the place as tidy as possible.”

“The plant is always located upon the water’s edge or at the head of a long wharf, and the fresh sea breeze comes in at the broad doors refreshing workmen. If one glances up, he sees the broad stretch of bay dotted by the white-winged boats or the restful green of spruce-bordered shores. Far better it is, despite the unpleasant odors attending this industry, than the close confinement of city shop or mill.”

“The small steamers fly up and down the bay until a cargo is obtained from the smaller boats, and then turn toward the wharf after the signal of one, two or three whistles, which indicate the number of hogsheads, and by which signal the men at the factory judge the number of cutters necessary. It is a pretty sight to see the silver shining herring poured from the boats. They glisten in the sun like liquid metal as they are dipped upon the long tables ready for cutting. The fish chosen are small herring, those from three to five inches long being the most desirable. The sardine of the Mediterranean ports is of this genus.”

“The heads and tails are removed, and then they are soaked and salted in huge tubs, dried and toasted in the large ovens, and then comes the packing, one brand being packed in mustard and others in plain oil. The work of the sealers is difficult, but when the art is once conquered it is pleasant work and a good workman earns from three to four dollars per day. He has a small charcoal fire beside him, a strip of tin half an inch wide in one hand and a soldering iron in the other. The can is placed upon a revolving plate in front, and with a dexterous movement, so quick one may not say how, the can is hound about and sealed with the private mark of the workman upon it, and slid off into the pile. These cans are then carried to the immense heaps of sawdust which cleans the oil or other dirt which it has gathered in handling. From this burying it is shoveled into a slanting sieve which removes the sawdust, and it is then ready to be packed in cases for shipment.”

“One scarcely realizes when he opens a box of sardines, how many different classes of labor have made it possible for him to enjoy this simple article of food. But one fully realizes the immense number of American sardines shipped to all parts of the country when he stands upon the deck of the homeward bound steamer, and, at every point, impatient of delay, he watches the innumerable neat cases run down the gangplank.”

Daniel and the other two boys in this photo look like they have some tough work ahead of them. When the fishing boats were about to come in with their catch, the whistle would sound, and workers, whatever age, had to drop whatever they were doing and head down to the “fish factory,” as the locals called it. The little boy on the left is probably having a hard time keeping up with the man who is dumping the fish on the table. And poor Daniel, with a big knife in his hand, is going to have to cut as many fish as he can (as fast as he can) without slicing off a finger. Other Hine photos at this factory show children as young as seven doing this kind of work.

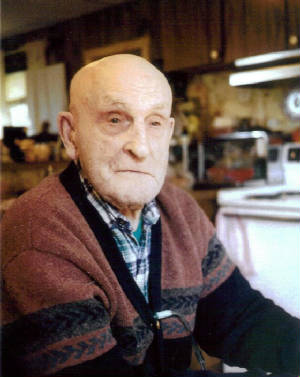

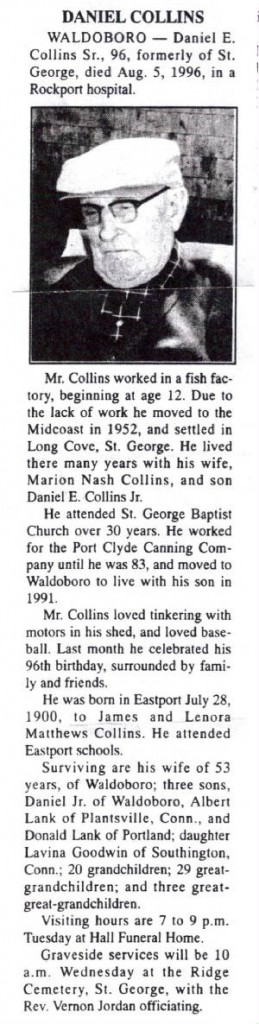

It didn’t take me long to find Daniel’s death record and obtain his obituary from the library near the town in Maine where he died. It turned out that he had a living son with the same name. He lives in Waldoboro, Maine, about 175 miles southwest of Eastport. I called him up, and he had never seen the pictures.

Daniel Eugene Collins was born July 28, 1900, in Eastport, the son of James and Lenora (Matthews) Collins. Also natives of Maine, they were married in 1879. Daniel was their youngest child. According to the 1910 census, Daniel’s father ran a tobacco store. But in 1920 census, he is listed as a cannery worker, along with his wife and three adult children, including Daniel. In the 1930 census, Daniel is still living in Eastport with his parents, and still working at the cannery.

He married Marion Nash on December 19, 1943. On August 5, 1996, he passed away at the age of 96. His wife passed away four years later at the age of 93.

Edited interview with Daniel Collins Jr (DC), son of Daniel Collins. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on September 4, 2008.

JM: Were you surprised by the photograph?

DC: I sure was. It was strange to see him at 11 years old. He told me he started working at the fish factory when he was real young. He said it was hard work. He said all the other kids had to work there, too, and that his father made him work.

JM: Did you know his parents?

DC: No.

JM: When were you born?

DC: I was born in Eastport in 1945.

JM: Did your father work at the fish factory when you were growing up?

DC: He worked in the fish factories most of his life, in the summertime.

JM: Did you ever work there?

DC: No.

JM: Where did he work the rest of the year?

DC: Sometimes he didn’t. He said he would have to borrow money from the town, but he would always pay it back.

JM: How long did your father stay in Eastport?

DC: When I was about 10 years old, we moved to Long Cove, in St. George, Maine. That’s near Rockland (about 175 miles south of Eastport). The reason we moved there is because my mother had a change of life and it was bad for her. She had sisters and brothers in St. George. So my dad left Eastport and took her there. Can you imagine the love he must have had for her that he left his homestead just for her? It was a big sacrifice. When he married my mother, she already had three kids. Her husband was a drinker, and he had left her. He treated those kids like they were his own.

JM: How many kids did he have by your mother?

DC: Just me.

JM: So were you closer to him than your half-siblings?

DC: Well, I guess I was the apple of his eye. I was named after him, Daniel Eugene Collins Jr.

JM: When you moved to St. George, what did he do then?

DC: He worked in the fish factory.

JM: What kind of work was he doing?

DC: He cooked fish, right in the cans. They would have these big boilers that they cooked them in, and then they would take them down and put them in bins. Sometimes he would put trays under the ladies’ tables for them to put the fish in after they packed them in the cans. He would go to work at 7:00 in the morning, and sometimes he wouldn’t get home till 3:00 the next morning. He’d do that in the summer. In the wintertime, he would work in the schools doing painting and stuff like that. He also worked in construction a little bit.

JM: Was your family always struggling, or do you think they were pretty well off?

DC: Both my mother and father worked. They put in long hours. My mother packed fish. In the wintertime, she took care of three kids for a woman who was working. We weren’t rich, but I had a good childhood. They didn’t owe any money when they died.

JM: How big was your father?

DC: He wasn’t very big. He was only about 5′ 2″. But he was strong. He was known for his strength.

JM: What was your father like?

DC: He had a dry sense of humor. He’d say things, and you would never know if he was kidding or not. Like one day, just as serious as anything, he looked at my mother and said, ‘My first wife weighed 400 pounds.’ He never even had another wife. He was proud of his Irish heritage, and he was proud of his father and mother. He said that when he was a kid, when his father built the homestead, he remembered running back and forth on the rafters.

JM: In your father’s obituary, it said he loved baseball.

DC: He talked about it a lot. He told me all about Babe Ruth. He also liked boxing. He said that he saw John L. Sullivan fight, down in Boston. I think he went to Boston at one time and worked on the railroad, when he was younger.

JM: How far did he get in school?

DC: He never talked much about school. I asked him about it once, and he just said that he went for a little while. He could read and write, and he was sharp in math. He taught me the times tables. He was self-educated. I used to hear people say that if he had gotten an education, he could’ve gone real far in life.

JM: Lewis Hine was trying to show that it was bad to have kids working, and that they should be going to school. How do you feel about that?

DC: I think it’s good for kids to work, but I don’t know about with those knives and stuff. Those kids were getting hurt.

JM: Did you finish high school?

DC: I didn’t. I went in the Coast Guard, but I ended up getting a GED.

JM: What kind of work have you done?

DC: I’ve worked in construction. I’ve worked on boats. I have a small seafood business, which is in Connecticut. My half-sister and half-brother live down there.

JM: Have you ever felt that you might have been better off if you had left Maine and lived somewhere else?

DC: I’ve been to quite a few states, but I always come back to Maine. I like to be around the water.

JM: Was your father a veteran?

DC: No. They wouldn’t take him because one of his eyes was bad.

JM: His obituary says he worked till he was 83 years old.

DC: That’s right. He had to stop because of problems with his eyes.

JM: Why did he work so long?

DC: He liked it. When he wasn’t on the job, he was always puttering around. He would come and visit me, and he couldn’t sit still. He was always tinkering with something. If his eyes hadn’t failed him, he would have stayed at the factory even longer. I moved him here to Waldoboro in 1990. My mother had Alzheimer’s. I had some land, so I put a trailer on it, and they lived right next to me.

My father lived to be 96, and he was sharp right to the end. He was born premature. He didn’t weigh very much. The doctor said that nothing could be done for him, and that my grandmother should just take him home and keep him warm. He was the youngest son, and he lived to be the oldest. My mother died four years after he did.

JM: Do you ever go back to Eastport?

DC: I go back every year to see the Fourth of July parade. We take all the kids and camp at Keens Lake, and stay for about three days. My old homestead is still there, at 7 Gilman Street. I have wonderful memories of Eastport.