Lewis Hine caption: Dora Nevins 12 years old. Been selling 1 year. Location: Hartford, Connecticut, March 1909, Lewis Hine.

“She was a homebody. She liked to cook. She made a good chicken soup.” -Harold Basch, son of Dora Nevins

The following was written by the editor in a 1909 edition of The Outlook, a newspaper. It appeared as the introduction to “Day Laborers Before Their Time,” a story with pictures by Lewis Hine. One of those pictures was the one above of Dora Nevins.

“Hartford, the capital of the State of Connecticut, is one of the most prosperous and beautiful cities in New England – and New England is not uncommonly nor unreasonably supposed to be the most enlightened section of the United States. The figures of the last census gave the city a population of eighty thousand inhabitants, and its unusual wealth is indicated by the single fact that the total assets of the fire and life insurance companies which have their head offices in Hartford and are the creation of Hartford capital and skill amount to one hundred and seventy-five millions of dollars. Hartford is the seat of Trinity College and one of the chief theological seminaries of the Congregational Church; moreover, its public school system is an admirable one, and it spends annually on these schools a sum amounting to between three and four hundred thousand dollars. Thomas Hooker, the famous clergyman and statesman of colonial times, a graduate of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, England, in 1608, was a citizen of Hartford, and is by some historians called the father of American democracy, which gives Hartford an excellent claim to the title of being the birthplace of that democracy.”

“If, with all these historical, social, and material advantages, such conditions can prevail among the newsboys and newsgirls of Hartford as are portrayed in the accompanying illustrations from life, no argument needs to be stated to prove the need of such an organization as the National Child Labor Committee, in the process of some of whose investigations the photographs were taken upon the streets of Hartford. Under the auspices of the State Consumers’ League and the National Child Labor Committee, a bill was introduced last winter to remedy some of these conditions, but it was rejected by the State Senate. Our able contemporary, the Survey, points out the significant fact that on the same day that this bill was rejected, the Connecticut Senate passed a bill providing that women and children may be employed in shops and department stores every night of the year until ten o’clock, and without any limit whatever as to hours of work in the week preceding Christmas. No doubt there are other cities where the conditions of newsboys and newsgirls are quite as bad as those prevailing in Hartford, but the retort of tu quoque will not serve to remove from Hartford the distinction of setting today a typical if not a flagrant example of American indifference to the welfare of children made day-laborers before their time.”

**************************

I fell in love with this photo immediately. It is unusual for Hine. The girl is not looking at the camera, and there is no sense that she is in any distress. The fact that she is looking to her right invites all sorts of possible explanations. Was someone calling out to her? Was she facing away from a cold March wind? Was she camera shy? Was she eyeing a potential customer heading her way? The photograph was one of about 40 Hine took of newsboys and newsgirls in Hartford, from about March 4 to March 8, 1909. The identity of the newspapers she was holding is a mystery. I blew up the photo and was able to read two of the headlines, but in an archival search of the Hartford Courant and Hartford Times, the two major area publications at the time, neither headline appeared, so one can only guess what newspaper she was selling.

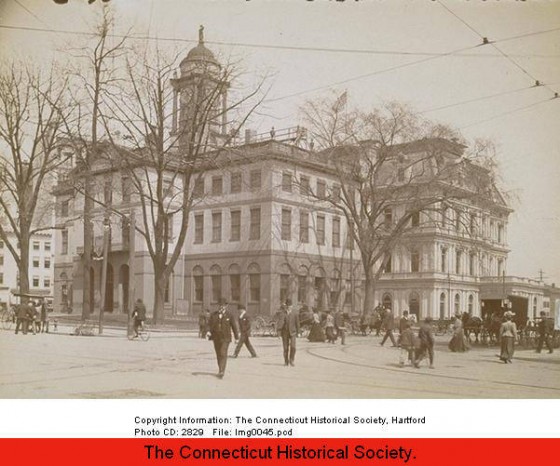

I live only 45 minutes from Hartford, so I was excited about the prospect of doing some onsite research. Right away, I wanted to know where the picture was taken. I assumed that someone would be able to recognize the attractive building behind Dora, so I emailed the photo to the Connecticut Historical Society, in Hartford. In a few hours, they identified it as the Old State House, which still stands at 800 Main Street. Having lived in Connecticut from 1970 to 1999, I had seen it many times. I made plans to go there and attempt to take the picture from the same spot, 100 years later. But first, I had to find Dora’s descendants.

In only a few minutes of searching on Ancestry.com, I found a Dora Basch in the Connecticut Death Index, which included the surname of her father, Nevins in this case. Her husband was listed as Frank. They appeared in the 1930 census, with four children, one of which was Harold I. Basch, not yet one year old. I found a Harold I. Basch in the Florida listings of the Internet White Pages, and called him up. I spoke to his wife, Wilma, who confirmed that Dora was her late mother-in-law. I emailed them the photo, and they were surprised and delighted. Several weeks later, I interviewed them. Meanwhile, I spent several days on the computer digging up more information, and then I headed to Hartford for some research and picture taking.

Most official records indicate that Dora was born in 1899, but her immigration manifest, often unreliable, indicates she was born in 1897. Dora’s son and daughter-in-law have always been under the impression that Dora was born in January of 1899, so it seems reasonable to accept that fact. So her age at the time of the photo was likely 10, not 12, as Hine specified. Her father, Rubin Nevins (also known as Abrahim Navinsky), landed at Ellis Island on September 9, 1905. His wife, Anna, and four daughters, including Dora, the oldest (listed as Dweine Navinsky in the manifest), landed at Ellis Island on May 31, 1907. All had been living in Grodno, Russia, where there was a sizeable Jewish population. The Nevins family was Jewish. The family was to have one more child, another daughter, born in Hartford a year later.

Ruben was a carpenter, later a building contractor. The family initially lived at 107 North Street, near a railroad yard. The street has since been replaced entirely by the Hartford Graduate Center and the Dodge Music Center, according to the Connecticut Historical Society. In 1912, three years after Hine photographed Dora, her mother died of heart failure at the age of 34. At that time, they were living at 5 Pequot St, which is no longer a residence address. Dora married Frank Basch about 1919, and they lived for a while with his parents, before renting a house at 73 Plainfield St, and then buying a house at 203 Branford St, both addresses near the University of Hartford, in the Blue Hills section of the city. Dora’s father died in 1932.

By looking at the 1906 photo of the Old State House, I was able to pinpoint where Dora was standing when Hine photographed her. The front of the building at 800 Main Street is on the east side of the street. After consulting several photography experts, I estimated that the photo was taken about 2:00 pm. That was in March, and this was August, but I was not about to wait until next March, so about 1:55, I placed the picture on the sidewalk across the street from the Old State House, and got out my camera. Hine would have been standing out in the street, much closer to the building, but that was not possible due to the heavy traffic. I managed to get several brief opportunities to shoot without traffic when the lights in both directions turned red, so that’s why there are no cars in the picture.

I determined that I needed to use my 75-300 zoom lens in order to approximate the view that Hine saw in his camera. Because he used a 5 x 7 view camera, and I used a SLR 35mm camera, it was impossible to duplicate the photo perfectly. Thus, my photo shows less space to the right of the building than Hine’s photo. While taking the pictures, two teenagers (boy and girl) stopped and asked what I was doing, and when I showed them, they were amazed that the building was 100 years old, and that it looked essentially the same. They wanted to know more about Dora. I suggested to the girl that I buy her a newspaper and then have her pose for a picture in the same position as Dora. I offered to give her a copy, and a copy of Dora’s picture as well. She was intrigued by the idea, but politely declined.

Edited interview with Harold Basch, son of Dora Nevins, and Harold’s wife Wilma. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on July 14, 2009.

JM: What did you think of the photograph?

Wilma: My family was thrilled with it. A lot of people thought she looked like my daughter. My nephew’s wife is involved with a museum in California. She sets up photography exhibits, and she’s familiar with Lewis Hine’s work. She was very excited that a famous photographer took Dora’s picture.

JM: What do you think about the fact that she was selling newspapers on the street at the age of only 12?

Wilma: We were flabbergasted, because she was a very quiet, sort of meek woman, and we never thought she would be doing that.

Harold: It was sad that she had to do it.

Wilma: However, we noticed that she was very nicely dressed. Her coat looked stylish for those times.

JM: What were her parents’ names?

Wilma: We don’t know. They died before my husband was born. Her mother died when Dora was very young. My husband’s sister said that’s probably why she had to go out and sell newspapers. She was the oldest of five girls.

Harold: Her sisters were Betty, Rose, Sarah and Bessie.

JM: Was Dora born in Poland?

Harold: Yes.

Wilma: Unfortunately, she never talked about when she was a child and coming over from the old country.

JM: Did your mother and father speak Polish?

Harold: They spoke only English as far as I know.

JM: When were you born, Mr. Basch?

Harold: 1929. I was the youngest. I had a brother and two sisters. Herbert died about two years ago, and Gloria and Bernice are still living.

Wilma: We emailed Dora’s picture to them right away.

JM: What was your father’s name?

Harold: Frank Basch.

JM: What kind of job did your father have when you were a boy?

Harold: He was a delivery man for a produce wholesaler that delivered to restaurants and supermarkets. The company was Charles Basch & Co. Charles was his brother.

JM: Did he work in any other job in his life?

Harold: Not as far as I know.

JM: Did your mother work when you were a child?

Harold: No. I don’t think she ever worked when I knew her.

JM: How did the Great Depression affect your family?

Harold: Well, we didn’t have to worry too much about food, because of my father’s job. He always brought extra food home and gave some to the neighbors. They looked forward to him coming home with baskets of apples and oranges.

JM: Where were you living when you were born?

Harold: At (73) Plainfield Street, and then (203) Branford Street, both in Hartford. The house on Plainfield Street was a two-family house, but the one on Branford Street was a one-family house. We owned it. It was in a nice neighborhood, right off Blue Hills Avenue. My family is Jewish, and there were a lot of Jewish families in the area who came from Russia and Poland.

JM: What was your mother like?

Harold: She was very pleasant.

Wilma: She loved all of her family and never had a bad word for anybody.

JM: Did you finish high school?

Harold: Yes. I graduated from Weaver High School in 1947. Then I went to the University of Connecticut.

JM: What did you study in college?

Harold: Microbiology. When I graduated, I was drafted into the army. That was during the Korean War, but I stayed in the States. I was in the army for two years. Then I went back to school, this time to the University of Massachusetts in Amherst. That’s where I met Wilma.

Wilma: I’m from Boston. I was going to UMass also. I majored in education and became a teacher. We lived in Amherst for five years after we got married. Our kids were born in Northampton, our daughter in 1957, and our son three years later. We moved to New Jersey in 1960, and I started teaching there in 1966. We moved to Florida in 2006.

JM: Did Dora live in Hartford her whole life?

Harold: Yes.

JM: When you lived in New Jersey, how often did you see her?

Harold: Several times a year.

JM: Did she have some interests outside the home after the children grew up?

Harold: She was a homebody. She liked to cook. She made a good chicken soup.

Wilma: When we came up to visit, she even liked to cook for our dog. And she loved to be with her grandchildren.

JM: When did your father pass away?

Harold: 1975.

JM: Your mother lived until she was 85. Was she in good health most of her life?

Harold: Yes.

JM: How long did Dora live in the house on Branford Street?

Wilma: She was there until her husband died. She stayed there for a while, but then she unfortunately developed Alzheimer’s. So she moved in with her daughter. Then she had to go into a nursing home.

JM: When was the last time you were in Hartford?

Wilma: About a year and a half ago.

JM: Is the house on Branford Street still there?

Harold: Yes. We drove by it.

Wilma: The neighborhood has been very well maintained.

JM: What are some of the things that you remember the most about Dora?

Wilma: She just loved to cook and bake.

Harold: I loved her potato pancakes.

Wilma: And her chocolate chip cookies. Every time we came, she would make them for the grandchildren. She made a banana cake that is like a family tradition. In fact, she gave me the recipe. Being a homemaker and mother and grandmother, that was her life.

Boy in front is Harold Basch (son in the interview). Back row (L-R): Dora Nevins, children Gloria, Herbert and Bernice, and husband Frank on the right.

Dora Nevins died on April 18, 1984, at the age of 85.

“She was a wonderful, sweet, kind, loving woman.” -Susan Weinstein, granddaughter of Dora Nevins

*Story published in 2009.