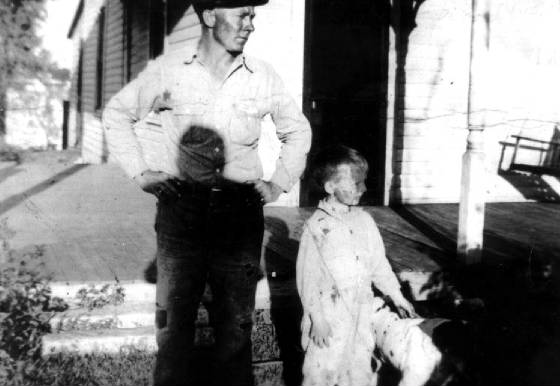

“Lewis Hine caption: Edgar Kitchen 13 yrs. old gets $3.25 a week for working for the Bingham Bros. Dairy. Drives dairy wagon from 7 A.M. to noon. Works on farm in afternoon (10 hours a day) seven days a week–half day on Saturday. Thinks he will work steady this year and not go to school. See previous labels in June. Not in Div. 5 or 6. Lives in Bowling Green. Location: Bowling Green [vicinity], Kentucky / Lewis W. Hine, August 18, 1916.

There are nine Lewis Hine photos of Edgar on the Library of Congress website, all of him working on the farm. All have substantially the same captions. I located his son, James, and sent him the photos, then interviewed him several weeks later. He told me that his father had told him many stories about working on the dairy farm as a little boy, but this was the first time James had seen any photos of his father at that age. On the next several pages, there are more photos, and my interview with James Kitchens, who still lives in Bowling Green.

Interview with James Kitchens (JK), son of Edgar Kitchens. Conducted by Joe Manning (JM), on September 11, 2007. Transcribed by Jessica Sleevi and edited by Manning.

JM: You saw the photos, right?

JK: Yes I did, and I was sure glad to get ‘em. I sure appreciate it.

JM: What did you think of those photos?

JK: I just really couldn’t believe it. I absolutely could not believe it. All of these years, and then something like that would come up.

JM: How old are you, sir?

JK: I’ll be 75 next month. I was born in 1932.

JM: You told me when I briefly talked to you before that you knew your father did this kind of work as a child. You told me that he told you a little about it.

JK: Yeah, he did. He had a younger brother and a younger sister that were still at home. And back in those days, the older folks like his mom didn’t have any means of support whatsoever. So my father worked out there on the dairy farm, and he had a brother that worked there, too. If I’m not mistaken, it was around three dollars or a little better a week that they made.

JM: Well, that’s what the caption actually said. It said he made $3.25 a week.

JK: He told me stories about that. And he said him and his brother would come home at the end of the week and bring what they made and give it to their mother. And she would allot each one of them a dime a piece. And that’s what they had to spend, a dime a week.

JM: What was his brother’s name?

JK: Herman.

JM: When did you lose your father?

JK: He died in ’73.

JM: What did your father do when he grew up?

JK: When I was four years old, we moved to a cemetery, and he was caretaker for five years. He mowed the lawns and dug the graves by hand. All that was done by hand back in those days. They furnished us a house. That was St. Joseph’s Cemetery in Bowling Green. And when we left there, he got in the timber business, and Dad done real well for a while. Dad was one of those kinds of fellows that was just sort of happy-go-lucky. If he had a pocket full of money, he didn’t worry about it ‘til he run out, and then he’d make some more. He got real good at buying and selling timber. He was at it so long, that he could go through a truck of timber and estimate how many board feet was in it. But he didn’t have much education. He could barely sign his name. He did it all in his head.

JM: When did he stop doing that job?

JK: He did it ‘til he got to where he wasn’t able to work.

JM: What kind of house did you live in?

JK: Well, we just lived in a small, maybe two-bedroom house.

JM: What was your father’s full name?

JK: Dad’s full name was Edgar Leslie Kitchens, but his nickname was Doc. And the reason his nickname was Doc was that he was the seventh son. And I don’t know that you know about that or not. Back in those days they believed the seventh son had the powers to heal people. And he told me that when he was growing up, neighbors would bring their kid over with warts, and he’d rub the warts and they thought they would disappear and stuff like that. It’s an old-timey way of thinking about things. That’s how he got the name of Doc, and he went by that all his life.

JM: When he was called upon to do healing, did he have any faith that he might be doing something good?

JK: Yes, he did. And his mother did, too.

JM: Your mother was Adeline?

JK: That was my mom.

JM: And when did she die?

JK: Well, it was eight months after Dad died. She had a stroke and Dad was taking care of her, and we thought, you know, that she was a lot sicker than my dad. But my dad had a heart attack, and he died before she did.

JM: Did you go to college?

JK: No. But I had a brother that did. He went to Western Kentucky.

JM: What did you do for a living, sir?

JK: Well, I went in the army. I was drafted in ’52. I worked for the Pet Milk Company in Bowling Green for 24 years. I drove a truck and I worked in the laboratory testing butterfat. People that sold milk to the company, you know, I’d check the butterfat in their milk.

JM: You said that your father told you stories about working on the dairy farm.

JK: Well, one story I can remember. He said he had got hold of a bicycle. And one morning he was going to work, way before daylight. And it was just gravel road back in those days, and he said it was a real moonlit night. He said this big, huge black fellow jumped right out in front of the bicycle and grabbed the handlebars. He said he had never been so scared in his life, ‘cause he had no idea what it was all about. He said he looked at the guy dead in the eye for what seemed like a couple minutes. And then the guy just stepped aside, and my father rode off. He never did find out what the reason for it was.

JM: The other guy might have been as scared as he was.

JK: Yea. It might have been that he thought my father was somebody else. You know, my father lived four or five miles away from where he worked.

JM: So he would have had to go four or five miles on a bicycle?

JK: Or walk.

JM: So in addition to working long hours, you would have to add the hours for just getting to and from the job.

JK: That’s the reason he left before daylight. I also got a story about the first automobile my dad ever saw. I don’t know the man’s name, but this man had the first automobile in Bowling Green. And Dad was at a grocery store, and this guy was there, and Dad asked him if he could ride in it. Well, he gave him a ride, so Dad told him where he wanted to go, and when he got to the place where he wanted to get off, he hollered and told my dad, “Jump, because it’s too much trouble for me to start and stop this thing.” So he jumped off and didn’t realize how fast he was going and tore his knees and his arm.

JM: When the pictures were taken, he was 14. Do you have any idea how long he had worked there, or how young he was when he started working there?

JK: No, I don’t.

JM: About how old would he have been when he stopped working there?

JK: I don’t know. He never told me.

JM: How big was your father?

JK: Well, my dad was a short man, about 5’6”, and stout. He probably weighed 160 to 180.

JM: In the picture where he’s holding a crate with bottles in it, he looks like a very handsome young man.

JK: I always thought he was.

JM: How many brothers and sisters do you have?

JK: I got one brother and three sisters.

JM: Where is your father buried?

JK: Fairview Cemetery, in Bowling Green. You know, me and my dad was awful close. From the time I was big enough to get around, I was with him practically every day. And even after I got married and raised my family on my own, I either saw him or talked to him practically every day. We were that close. After I come back from the service, I bought a farm and he was living in town. Dad always liked to farm in the rural areas, you know, and he spent a lot of time with me out here on my farm in his later years.

JM: Lewis Hine was on a mission to go around the country and take pictures of children working in order to get child labor laws passed. Many of the situations that children were photographed in were far worse than your father’s was, such as in coal mines. And some in cotton fields or in cotton mills. Sometimes the pictures were pretty horrible. What do you think about Mr. Hine taking a picture of your father? Do you think he was making a good point?

JK: I think he was, yes I do. I think probably a lot of the factories or places didn’t let him in to take pictures. And then in rural areas like in my dad’s setting, they probably didn’t care if he took the pictures.

JM: I’m sure you wonder now whether your father knew about the pictures.

JK: That’s right. I don’t know whether he ever knew about it or not. He never mentioned it to me. When Mr. Hine came to Bowling Green, he must have traveled by rail, ‘cause by that time Bowling Green had a track through here and had the L & N Railroad.

JM: So he would have made a stop right in Bowling Green.

JK: Yeah, right. Do you know whether his pictures had any effect on child labor laws?

JM: They most certainly did. He took thousands of pictures between 1908 and 1917. Many organizations were promoting the passage of child labor laws, and they used the pictures as publicity to awaken people’s consciences. But many families at that point were still dependent on their children working. And so, just like you said, he made this money and brought it home to his mother.

JK: He did. I have no idea what she would have done, if it hadn’t been for that.

JM: I’ve always felt that the people who have the most impact on history are the everyday people who go about their business and do their work. They built the country and don’t get the credit for it. And I’m sure Mr. Hine would have thought that your father contributed just as much to history as the famous people. He had a lot of respect for work.

JK: Well, Dad was an honest man. Like I say, he never did accumulate much, but what he made, he made honestly.

Edgar L. “Doc” Kitchens was born on March 25, 1902, and died in Bowling Green, Kentucky, on October, 28, 1973, at the age of 71.

*Story published in 2008.