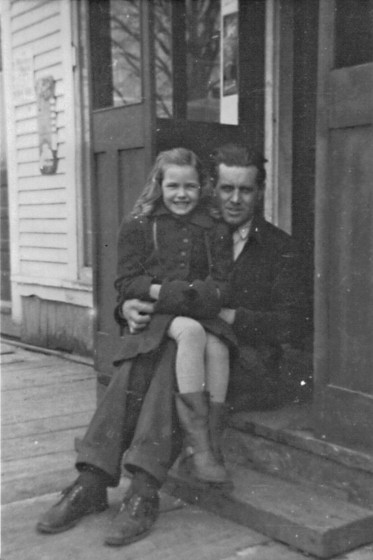

Lewis Hine caption: George Goodell, and butcher knife used by many children. Location: Eastport, Maine, August 1911.

“I think he (George) was devastated when his mother died. I remember him telling me that he had to quit school in fifth grade to feed his younger brothers and sisters. I sensed that he had liked school and wished that he could have continued. However, there was never any resentment about having to work to support others. Later in his life he emphasized the importance of education, stating that was the only way to get ahead. -Peggy Boone, niece of George Goodeill

“He (George) had a store in Eastport, with my husband in the family, and he did all of our sales taxes and bookkeeping. The state came down one time and looked at his books. Dad had all of the receipts stuffed in boxes, and I said: ‘Oh my goodness, we’ll probably get in trouble.’ But this guy sat at the desk with his glasses on and went through every one of them boxes, and Dad had it right down to the penny. Dad was really something else, I’m telling you. He was a great person, and somebody should write about him.” -Carlene Cook, daughter of George Goodeill

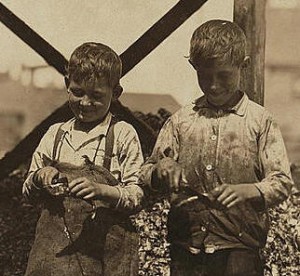

Lewis Hine caption: Clarence Goodell, showing how he does it. Location: Eastport, Maine, August 1911.

“My uncle (Clarence) was a great guy. He could play the piano. He was awful nice to us, and he was smart, too. He was really big. He was a boxer in his younger days. Mom told me they called him Tiger Goodeill.” -Carlene Cook

I had no difficulty finding descendants. George’s Social Security death record was readily available on the Internet, confirming that his name was spelled Goodeill. The Bangor Public Library was happy to send me his obituary, from the Bangor Daily News, and that’s all I needed to find one of his daughters, and one of his nieces. Interviews with both of them are included in this story. I also found a website devoted to Goodeill genealogy, from which I confirmed data such as birth, marriage, and death records.

Lewis Hine caption: Three cutters in Factory #7, Seacoast Canning Co., Eastport, Me. They work regularly whenever there are fish. (Note the knives they use.) Back of them and under foot is refuse. On the right hand is Grayson Forsythe, 7 years old. Middle is George Goodell, 9 years old, finger badly cut and wrapped up. Said, “the salt gets unto the cut.” Said he makes $1.50 some days. Left end, Clarence Goodell, 6 years, helps brother. Location: Eastport, Maine, August 1911.

“The real problem in America is not child labor, but child idleness. You cannot convince me that it hurts a child (age 4+) either physically or morally to make him work. Where one child has been injured from work, 10,000 have gone to the devil because of lack of occupation” -Charles S. Thomas, US Senator from Senator from Colorado from 1913 to 1921

According to A History of the New England Fisheries, by Raymond McFarland, published in 1911:

“The first cannery for sardines was built at Eastport in 1875. During each of the succeeding years, one new cannery was added to the number so that in 1879, there were five in operation. In the spring of 1880, eight more were built at Eastport, and one each at Robbinston, Lubec, Jonesport, Lamoine, and Camden, making eighteen in operation in the State. By 1886 there were thirty-two canneries in operation at Eastport and the neighboring places. Along the coast, scattered from Cutler westward, there were thirteen others in operation, making forty-five canneries in Maine in 1886.”

“In 1899, two companies were formed, known as the Seacoast Packing Company and the Standard Sardine Company, which included most of the canneries in Washington and Hancock Counties. The Seacoast Packing Company eventually absorbed its younger rival, and a number of the more antiquated plants were discontinued. Some of the canneries were fitted with new and improved machinery and were thus rendered more effective than formerly. Eleven plants at Eastport, owned by the Seacoast Packing Company, were not operated in 1902. This company was reorganized in 1903, and a greater number of its canneries were sold.”

The company that emerged from the reorganization was called the Seacoast Canning Co, the site of over 50 child labor photos taken by Lewis Hine in August of 1911. At least seven of those photos contained members of the Goodeill family. The two of George and Clarence, demonstrating their prowess with a butcher knife, were among Hine’s most shocking pictures.

George Garfield Goodeill was born in Eastport, on August 7, 1900; and Clarence Goodeill was born in Calais, Maine, on May 12, 1903. They were among at least eight children born to Solomon Goodeill and Margaret May Stein, who married on February 20, 1897, in St. George, New Brunswick, Canada. Solomon was born in St. George in 1868, and died in 1948. Margaret was also born in St. George, in about 1879, and died in 1914, at the young age of 35. George married Edna Cox and had two daughters. Clarence married Hilda Flagg and had a son and two daughters. George passed away on March 18, 1987, at the age of 86; and Clarence passed away in March of 1954, at the age of about 51.

![Interior of a cutting shed in Maine. Young cutters at work, Clarence, 8 years, and Minnie, 9 years. Photo does not show the salt water in which they often stand, not [i.e., nor?] the refuse they handle. On the low shelf are two of the "boxes" used as measures, and for which they get 5 cents a box. Location: Eastport, Maine, August 1911, Lewis Hine.](https://morningsonmaplestreet.com/files/2014/11/ClarenceAndGirl.jpg.w560h376.jpg)

Edited interview with Peggy Boone (PB), niece of both George and Clarence Goodeill. Conducted by Joe Manning (JM), on February 7, 2007. Transcribed by Seunghee Cha and edited by Manning.

JM: When did you discover these pictures?

PB: I had them long ago. Somebody had called from Eastport and told me they were in an exhibit there. I have them hanging in my house.

JM: How are George and Clarence related to you?

PB: Both of them are my uncles. They were my mother’s brothers.

JM: You told me that George became like a father to you?

PB: Right. I started living with him and his wife Edna when I was four months old. They loved my mother Lorena dearly and took me as a favor to her.

JM: How did that wind up happening?

PB: I was born in 1949, the seventh child of my mother, Lorena Goodeill Clossey. At the time of the delivery, she was a single mother. She was very sick with eclampsia, required a C-section, had five – maybe six – other children living at home, and was very poor.

JM: Had she been working?

PB: She worked seasonally in the fish cannery in Eastport.

JM: So when she became sick, is that why George started taking care of you?

PB: He had helped her a lot financially. He owned a grocery store in Robbinston, about 15 miles away. He used to bring down boxes of food to her for the kids. George and his wife Edna kind of fell in love with me, I guess. So I ended up living with them.

JM: And what happened to your mother at that point?

PB: She worked and tried to take care of her other children. And then she died, when I was 11, and she still had four other children living with her.

JM: And so you were living about 15 miles from your mother.

PB: Initially as a baby, I lived in Robbinston, but then George and Edna moved to Eastport and they lived next to my mother.

JM: Did George still run the store in Robbinston?

PB: No. I guess it was after the Depression, and he decided to give that up. He did odd jobs. For a while he worked at Guilford Industries, which was a woolen mill. And he delivered fish, and he worked in a gas station in Medway and used to come home on the weekends. He always worked, but there wasn’t really a lot of work, and he had left school in the 5th grade in order to take care of his siblings. His mother had died in childbirth. He worked at the cannery when he was a child, but I don’t know at what age he started. Later, his father loaned him some money and he went to Calais and bought some nuts and Christmas candy from a man named Frank Beckett, and then went from house to house selling it. He had a business mind from an early age.

There wasn’t anything that he couldn’t do. He was very innovative. He used to run a hot dog stand every Fourth of July in Eastport. And he used to take that hot dog stand to the Machias County Fair and to Woodland on Labor Day. He invented an electric potato peeler. He just took all kinds of old parts that he had and put them together. I remember the side of the machine was made out of some kind of metal sandpaper. The peeler consisted of a bucket lined with the metal sandpaper. It was on a metal frame and underneath there was a motor that thrashed the potatoes against the metal sandpaper, thus scraping the peelings. This was all made from spare parts that he had collected. We used it on the Fourth of July to peel many 50 lb. bags pounds of potatoes for French fries. He was really clever.

JM: Did he actually sell them to anyone?

PB: No, he didn’t. There was no way of disposing of the peelings. They just dropped on the ground. I remember a health inspector complaining about this one Fourth of July. But he was ingenious. There wasn’t much that he didn’t know, and not many subjects that he couldn’t carry on a conversation about.

JM: Did you refer to him as your father?

PB: I always did and will.

JM: What was his wife like?

PB: Edna was a dear, loving person, a beautiful lady. She was the ideal wife and mother. She had come from poverty, too, and had lost her mother at a very young age. She worked in George’s store in Robbinston. She and Lorena were great friends. The arrangement with me seemed to work perfectly with Lorena, Edna and George. There were no power struggles – just lots and lots of love.

JM: Did you refer to Edna as your mother?

PB: Yes, but I knew she really wasn’t. It was no secret or anything.

JM: Carlene, George’s daughter, was your first cousin, but did you feel as though she was your sister?

PB: Yes. I still do. She is a blend of George and Edna – kind, personable, loving, unselfish, intelligent.

JM: Did George ever talk about working in the cannery as a child?

PB: No, he didn’t. But I remember him telling me that he had to quit school in fifth grade to feed his younger brothers and sisters. I sensed that he had liked school and wished that he could have continued. However, there was never any resentment about having to work to support others. This was just an expectation, and others, including two of his older sisters Violet and Lottie, had done the same thing. Later in his life he emphasized the importance of education, stating that was the only way to get ahead. He also told me that a person never gets ahead by working for someone else, advice evidenced by his own business ventures. I never heard him say anything negative about anybody in his family or out of his family. And as far as I know, he had a very excellent relationship with his father. I think he was devastated when his mother died. He was serious about taking care of his younger sisters and told stories about working as a child and using the money to feed and care for his siblings. It seemed to be the family thing to do, for the eldest siblings to care for the younger ones.

JM: How did those sisters turn out? Did they get along alright?

PB: They did. They were all best friends. They seemed like happy people. I think they all began working at a very young age. The older ones took care of the younger ones. I’ve seen pictures of them as children, and their hair is all curled, and they seem to have nice clothes.

JM: Did you know Clarence very well?

PB: I did not. I remember when he died, but I was really young then. From what my brothers and sisters say, he was really a nice guy, and he was really popular and well liked, outgoing, and very athletic.

JM: Do you know what he did for a living?

PB: I know that he had trucks, and people delivered chum (fish waste used for fertilizer) from the fish factories for him. He was interested in boxing, and they used to have boxing matches at his house on Franklin Street. He was deeply admired by George and his sisters. His son Dale has four children, three girls and one boy, and they all went to the University of Maine, and they all majored in electrical engineering.

JM: You told me a story when I first talked to you about George helping you with your algebra homework.

PB: He could help me do that even though he quit school in fifth grade. He told me that he had been a good student in school and that my real mother Lorena, as well as the other sisters, had been excellent students.

JM: Did you just automatically go to him thinking that he would be able to help you?

PB: Sure. He could figure a lot of it out in his head.

JM: What else can you tell me about him?

PB: He had a really good sense of humor. He could always see the humorous side of things. At one point when he had the convenience store in Eastport, he took shoe polish and wrote a sign on the window of the store that said: ‘Beware of the eagles flying low. They might hit you in the head.’ Somebody from the Bangor Daily News took a picture of it, and then it was published. This was at the time the Pittston Oil Company was trying to build a refinery in Eastport but was facing arguments from environmentalists. He was for the refinery, having lived through the economic downfall of Eastport’s cannery business. His hero was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and he also greatly admired his wife Eleanor. He often spoke fondly of each of them and was a strong Democrat.

JM: Did you do a lot of things with him? Or was he always working?

PB: As a younger child, he used to let me follow him around as he did errands and odd jobs. He loved children, was extremely patient, and seemed to welcome and enjoy my presence. He was always working, but I worked with him at the store, from the eighth grade on. I used to work there in the summer. He just worked so hard, almost all the time.

JM: But he lived to be 86.

PB: He had a stroke, and he finally died of kidney failure. He was elderly the first time he was ever admitted to a hospital – Eastern Maine Medical Center in Bangor. I was with him and remember him being in a wheelchair, and they asked him what he did for a living. He told the nurse he was a clam digger. Like I said, he had quite a sense of humor.

JM: Did you go to college?

PB: I went to the University of Maine, in Orono.

JM: What did you major in?

PB: I majored in English and French – B.A. in English; later, an M.L.S. in Library Science.

JM: And now you’re a school librarian?

PB: Yes.

JM: Were you a teacher before?

PB: I was. I’ve been a middle school teacher, and a high school English and French teacher. When I see kids at school and I hear of these abuse cases, I think about what might have happened to me if George and Edna hadn’t taken me in. I think there was a couple that wanted to adopt me. It was a minister and his wife. Oh, my goodness, what would have happened to me? How would my life have been different if I had ended up with them? You know, it’s kind of scary.

JM: Do you think you’re anything like George?

PB: I work really hard, and I think I have a really good sense of humor.

JM: Did he try to teach you to do things, like those he did with his hands and his ingenuity?

PB: No. It was the fifties. Back then, girls did girl things and boys did boy things.

JM: Tell me more about George.

PB: He was just a real generous, likable person who worked really hard. He was really dedicated to his family. He loved Eastport, and he loved Washington County. He was a great father and a great husband.

JM: I’ve begun to realize that it’s important to find out about the lives of these kids. Many of them turned out to have normal lives, not necessarily privileged lives, but people who were loved and cared for by their children, and are part of someone’s fond memories. I wonder what Mr. Hine would have thought about this.

PB: I think there are two ways of looking at child labor. I know it wasn’t right, and I’m glad that it’s changed. But on the other hand, what would these people have had if they hadn’t worked? What would the quality of their lives have been like? It seems like everyone was doing it. It was kind of the thing to do if you lived in the area at that time. I don’t think they knew any different. The whole structure of society is different today. If they were young now, George and his siblings would be able to go college for free and consequently have greater economic opportunities. The greatest thing George and his family had was love – something not drained by child labor or guaranteed by educational opportunity.

Lewis Hine caption: Housing conditions in settlement at Seacoast Cannery #7, Eastport, Me., not very good. This is the home of the Goodell family. They live here all the year in these temporary quarters. The father works in the mill nearby. Four or five of the children are in the canneries. Clarence, 8 years; George, 9 years; Lottie, 12 years; “Makes a couple of dollars some days”; Violet, 15 years, “has made four dollars a day packing at times,” (see upper window). Location: Eastport, Maine, August 1911.

Edited interview with Carlene Cook (CC), daughter of George Goodeill and niece of Clarence Goodeill. Conducted by Joe Manning (JM), on April 2, 2007. Transcribed by Seunghee Cha and edited by Manning.

JM: I had a nice long talk with Peggy. She told me your father George was really her uncle.

CC: He was a wonderful father to her. She’s my cousin, but she’s just like my sister.

JM: When were you born?

CC: On June 1, 1934, in Eastport.

JM: At the time, where were you living in Eastport?

CC: Actually, we lived in Robbinston. My dad had a store up there. First he drove a truck. And then he and my mom got married, and he bought a store up in Robbinston. We lived over the store. And I was there until I was eighteen. The store was about all they had in the town. Then he started showing movies. He’d rent these movies from a guy over in Millbridge, and he would put a curtain up in the store, and all of the people in Robbinston would come and sit on boxes and counters, whatever. He’d put the cameras out and we’d shut the lights off and show the movies. And a lot of the old movies I see now on TV, I’ve seen them because Dad showed them. We had a grand time doing that. And then after a while he bought a very big waterproof movie screen and showed outdoor movies. Mom and I would go around with a hat and they would put some change in to help pay for the rent on the movies. I think Dad was the first one to have outdoor movies in this area of Maine.

JM: And this was in Robbinston?

CC: The outdoor movies were in Pembroke. They had the Pembroke Fairgrounds. They had horse racing on Sundays. In the summer, Dad had a hotdog stand there, and Mom and I worked in it. But it didn’t seem like work. It was fun. Dad was way ahead of his time. He was very smart. He had a convenience store. It was called Goodeill’s Cash Store. He sold Gulf gas. He opened that up like four o’clock in the morning, and he didn’t close the door until about ten or eleven, every day. Up on the hill, he had a beautiful piece of land. It would be worth money today. He had five or six camp cabins on it. So they rented the cabins in the summer, and people in the cities would come in from Massachusetts and spend the summer. Mom worked at the store, too, and helped out with everything.

JM: How far is Robbinston from Eastport?

CC: Fourteen miles.

JM: So when you went to the big city, so to speak, did you go to Eastport?

CC: Most of the time, we went to Calais. We went to the movies up there on Saturday nights, and they had band concerts Sunday nights in the park. And when they had the Fourth of July in Eastport, that was a big thing there the whole week. We’d have the hotdog stand there. And then we’d take the hotdog stand to Woodland for Labor Day weekend. And we’d go fishing. We had a boat. In those days, nobody had any money. But we had a store, so we were lucky. Dad had a new car, and we had a telephone in the store.

JM: When you were growing up, did you know that your dad had worked in the cannery?

CC: He never talked much about himself. Peggy and I thought about that the other day. He never discussed his family much to me. I think I knew that he had worked in the cannery, but I didn’t know that he was a little kid then. But he was very smart.

JM: Without having gone to school much.

CC: He didn’t have to go. I guess it was just a natural thing for him. He had a store in Eastport, too, with my husband and the family, and he did all of our sales taxes and bookkeeping. The state came down one time and looked at his books. Dad had all of the receipts stuffed in boxes, and I said, ‘Oh my goodness, we’ll probably get in trouble.’ But this guy sat at the desk with his glasses on and went through every one of them boxes, and Dad had it right down to the penny. Dad was really something else, I’m telling you. He was a great person, and somebody should write about him. I’ve often thought about it.

JM: Did your father have any other children?

CC: No, I have no brothers and sisters.

JM: Did you know your father’s father?

CC: I knew Grampy Goodeill. He used to come out to the store. And he was always dressed really nice. He always had a hat, a jacket and a tie.

JM: Do you know what he did for a living?

CC: He also had a store, a little grocery store in his house.

JM: What about your uncle Clarence, your father’s brother?

CC: My uncle was a great guy, too. He could play the piano. He was awful nice to us, and he was smart, too. He owned some dump trucks. Sometimes Dad would drive one of them. They’d get a load of chum and bring it back and fertilize the plants.

JM: What is chum?

CC: When they pack the fish, they cut the heads and tails off, and that’s chum. Clarence’s wife, Hilda, worked down in the factory. She was a good packer.

JM: He looked very much like your father, didn’t he?

CC: Yeah, he was bigger though. He was really big. He was a boxer in his younger days. Mom told me they called him Tiger Goodeill. I forgot to tell you that Dad invented a lot of things too. He invented a potato peeler. And he had a ferry boat that went from Calais to St. Andrews (New Brunswick). He had a big sign on the boat, with a picture of Uncle Sam shaking hands with the premier of New Brunswick, with the water between them.

JM: How did he have time to do all that stuff?

CC: Well, you know, he didn’t require much sleep. He’d go to bed at eleven or twelve, and he’d be up early with that flashlight. Dad would nap sometimes. He could sit in a chair and have a nice nap, and then wake up refreshed. He had a lot of energy. And he had a great helper in the store. His name was Bert Tuttle, and he was always at the store when my father was doing other things.

JM: When did he marry your mother?

CC: Oh, I don’t know, exactly. She was from Perry, just a little ways from Eastport. Her name was Edna Faye Cox. She was a beauty, my mother. She was like one of them movie stars with blonde hair. She always wore high heels, even when she’d be out there pumping gas.

JM: Did you have a career? Did you have a regular job most of your life?

CC: Mostly store business. We had a store here in Eastport, and it was called Cook and Goodeill. I was a Goodeill, and I married a Cook. So Mom and Dad and my husband and I all went in it together. It was a convenience store.

JM: Boy, stores sure run in your family.

CC: You better believe it, but I loved the store. I’d still be in one now if I wasn’t so old.

JM: It’s certainly a good way to meet people.

CC: Yeah, that’s what I liked about it.

JM: So I guess your father must have been pretty popular in town.

CC: Everybody liked Dad. Everywhere I go now, people still speak about him. Did Peggy tell you about the signs he made? Sometimes he’d take white shoe polish, ‘cause we had plate-glass windows up there, and he’d write signs on the store. There was a picture of one of them in the Bangor paper.

JM: When your father wasn’t working – if that’s possible – is there anything he loved to do for recreation?

CC: He loved to go visit people. I can remember going to different places, different stores, going in and talking to people. We used to go fishing on a lake. Or sometimes we’d go stream fishing. He liked doing that. He was interested in everything. He always read the newspaper, and he always watched the news on TV. And he liked those game shows. He loved ‘The Price Is Right.’

JM: Are there still some canneries up there?

CC: No, not anymore.

JM: Were there canneries when you were a kid?

CC: Yes. Down behind the store in Robbinston, there was a Seacoast Packing Company.

JM: That’s the company your father worked for in Eastport. When you saw that picture of your father with a big butcher knife in his hands, what did you think? He was only seven years old.

CC: I couldn’t believe it. I was shocked when I seen that knife in his hand and knew what he had to do, but he never said anything about it.

JM: Do you think most people there who are your age are aware that small children worked back then in the canneries?

CC: I don’t know, probably not until recently.

JM: Some of the other pictures I’ve seen were of kids with bandages on their fingers. One kid had cut his finger really badly.

CC: That’s amazing that it ever happened.

JM: I think that most people looking at those pictures now will say, ‘Well, that kid didn’t have a chance.’

CC: Obviously, but they pulled themselves up by their bootstraps.

JM: You look at the outcome of your father, and he survived and turned out to be very accomplished.

CC: I know. It didn’t seem to hurt him any, as far as morals go. He didn’t drink, and he didn’t smoke. I don’t think Clarence did either. Dad had such a good heart. At the store, he let people have all that stuff on credit; and when he left there, there were bills and bills that people never paid him. And he didn’t even try to collect, because they didn’t have any money, and they worked in the factory only in the summer. It was hard times for people, and he just let ‘em have it. He never said a word. You know, during the World War II, he closed the store up, believe it or not, and we moved out to Portland (Maine). His sister lived there. And they had an apartment right near them. Mom and I and Dad went out there, and Dad worked on the Liberty Ships in the Portland shipyard.

JM: So how long did he do that?

CC: I would say maybe two, three years. Mom was homesick. She used to cry. She wanted to come home to Robbinston and open the store again.

Clarence Goodeill (1903 – 1954) George Goodeill (1900 – 1987)

*Story published in 2009.