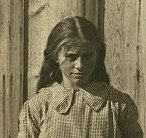

Lewis Hine caption: A case of “Economic Need.” Jacob Roomel [i.e., Rommel?] and his family live in this roomy shack, well-furnished, with a good range, organ, etc. They own a good home in Ft. Collins, but late in April they moved out here, taking contract for nearly 40 acres of beets, working their 9 and 10 yr. old girls hard at piling and topping (altho[ugh] they are not rugged) and they will not return until November. The little girl said, “Piling is hardest, it gets your back. I have cut myself some, topping.” The older girl said, “Don’t you call us Russians, we’re Germans,” (although they were most of them were born in Russia). Family been in this country eleven yrs. Location: Ft. Collins [vicinity], Colorado / Photo by Hine, Oct. 30/1915.

When I saw this photo, I thought about Howard and Eveline Butcher, a newly married teenage couple in Indiana, who left their families in 1874 and traveled by covered wagon to Kansas in search of a new life as young farmers. They would lose five of their 11 children in infancy. One of those who survived to adulthood was Jenny Christa Butcher, who gave birth to my father in 1911. I knew great-grandmother Eveline when I was very young. She was in her 90s then. I can only imagine the struggles she and her family must have faced. The Rommels would have faced similar struggles in Colorado, with the additional obstacle of being German-speaking Russian immigrants.

In 1915, Lewis Hine took about 100 photos of Colorado beet farmers such as the Rommels. The National Child Labor Committee was concerned that most of the children in these families had very little schooling. The following is excerpted from their 1920 report Farm Labor vs. School Attendance (public domain).

“The school term in the country is shorter than that in cities. In a comparison of rural and urban statistics made in 1912, the Bureau of Education reported that the average term in urban communities was 46.4 days longer than the average for rural communities. The actual difference between the term in city schools and in country schools is even greater, for the above figures include in ‘rural communities’ towns with a population of 2,500 or less, although the school term in such towns approximates that of the cities more nearly than that of the country regions.”

“This condition is usually attributed to the difficulty of raising funds in the country. Another factor enters in, however the tendency in many rural districts to subordinate education to farm work. The compulsory education law of Georgia, for instance, empowers the city, town and county boards of education to excuse children temporarily from attendance, and expressly authorizes them ‘to take into consideration the seasons for agricultural labor and the need of such labor in exercising their discretion as to the time for which children in farming districts shall be excused.’ Schools in Michigan frequently declare ‘beet vacations’ in the late fall.”

“The same thing is true in the beet-growing regions of Colorado. In one section, the schools opened November 29, and closed May 1, a term of only five months (less than the very low minimum required to entitle a state to receive federal aid under the proposed Smith-Towner Bill). To shorten the school term in accordance with the requirements of the farm is manifestly unfair. It not only permits children to miss school; it obliges them to.”

“The most serious effect of farm labor, however, and the one which has been made the special point of the National Child Labor Committee’s investigations, is the amount of absence which it causes. Children enter late in the fall, and leave early in the spring; even during the winter months they are absent from time to time to help on the farm.”

“In Colorado the local school authorities of counties in the sugar beet growing section estimated that 4,841 children between the ages of 6 and 15 miss from two to twenty-two weeks of school, with an average of nine and a half weeks, because of work in the fields. In one school, four rooms were reserved for beet workers, but when the school opened only 30 children enrolled. This number soon dropped to 21, the third month there were 58 children, and the fourth 125. The Juvenile Court of Weld County as the result of their investigation referred to above, concluded that, ‘by far the most of the children who are withdrawn from school to work are found on the farms.'”

“There are as in any child labor field two classes of families to be considered. There are those who do not need the assistance of their children, but who nevertheless allow and encourage them to stay away from school and work. This class constitutes a large majority. A (Colorado) family consisting of the father, mother and two girls, 9 and 10 years, worked 40 acres of beets, although they own a good home elsewhere in the state. They board it up for half a year, and live in a shack ‘in the beets.'” (Note: This is obviously the Rommel family, judging by the caption under their photograph.)

“There are some, however, so crushed by poverty that they do actually depend upon the work of the children for the support of the family. This should not be so. It is a short-sighted as well as an unjust policy to cripple the future of children because of present economic necessity. If forced to do without the help of the children, either the families would receive other assistance (such as scholarships or mothers’ pensions), or the conditions creating the poverty would be ameliorated.”

**************************

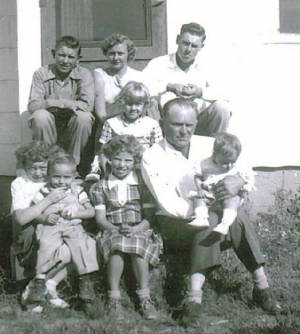

Shortly after discovering this photo, I found the family in immigation records and in the 1910 and 1920 census, living in Fort Collins, Colorado. They entered the US through Ellis Island in 1902, and went to Kansas. One of their children, Martha, was born about 1910, and her 2005 obituary popped up in a search of Colorado newspapers. I called one of her surviving daughters, Pat Speyer, and interviewed her and her husband a month later. According to them, Jacob Rommel was born on March 1, 1867, in Hussenbach, Russia, and died on June 21, 1944, in Fort Collins, Colorado. Jacob’s wife, Alice (Gietz), was born on Sept 15, 1868, also in Hussenbach, and died on April 14, 1933, in Fort Collins.

Lewis Hine caption: Rommel home, 430 N. Loomis St., Ft. Collins, Colo. Home boarded up for six months this year while family lived in the little shack shown in 4040. Location: Ft. Collins, Colorado / Photo by Hine 10/30/15.

Edited interview with Pat Speyer, daughter of Martha Rommel Karst, who was the daughter of Jacob and Alice Rommel; and Pat’s husband, Gerhard Speyer. Conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on September 24, 2007. Interview transcribed by Jessica Sleevi and edited by Manning.

JM: I understand that you have seen this picture before.

Pat: Some people sent it to my mother. They were doing the family history.

JM: Were you aware of the historic nature of the photo?

Pat: No.

JM: Do you know whether anybody in the picture mentioned this and remembered that they were photographed?

Pat: Nobody ever mentioned it. They’re all deceased now.

JM: What do you think of the photograph and what it is depicting about your family? It looks to me like they were having a difficult life at that time.

Pat: The stories we had from my mother is that they lived in a home in Fort Collins (Colorado), on Loomis Street, and they would also go out and work in the beet fields and live in a little house. And when the season ended, they would go back to the house in Fort Collins.

JM: One of the photos shows the house on Loomis Street. Were you ever in that house?

Pat: Not inside of it. My mom and dad lived a few blocks away on Sherwood Street, and when we drove by it, Mom would say that was where she lived. And she’d tell us all these stories.

JM: Your mother was Martha. Which one was she in the photo?

Pat: She was the little one. She was probably five years old then. The next sister was Lydia. She was probably nine. She married Fred Brunz. The one next to her was Molly. She married Frank Kinner. The older one is Elizabeth, or Betty. She married Clarence Geist. They had an older sister Alice, who married an Ellis, but she’s not in the picture.

JM: Did you know Jacob, your grandfather?

Pat: He died in 1944, before I was born.

JM: What about your grandmother?

Pat: She died quite young, in 1933. I remember we had pictures of her sitting in the rocking chair. After she died, my grandfather remarried.

JM: Who did he marry?

Pat: Oh gosh, I don’t know that.

JM: Did your mother have a job when she grew up?

Pat: She worked on the farm, and she also cleaned houses and stuff.

JM: So your father was a farmer?

Pat: We were sharecroppers.

JM: In Fort Collins?

Pat: Sometimes in Fort Collins. We also lived in Nebraska and Wyoming. In the winter, when he wasn’t sharecropping or farming, he would work in the sugar factories in Greeley (Colorado).

JM: Did any of the girls have a job or career when they grew up?

Pat: Aunt Molly worked for the state of California for many years. That’s all I know.

JM: You live in Florida now. When did you leave Colorado?

Pat: We moved to Texas in 1984, and then we moved to Florida about nine years ago.

JM: So up to 1984, you were still living in Colorado?

Pat: My husband was in the navy, and we were in California. But Colorado was still our home.

JM: What did you do for a living?

Pat: I worked in the office for the power company, and I worked in the hospital as a clerk. And my husband and I had our own business. We were cosmetologists for a long time.

JM: Did your mother talk much about her days of working on the farm and going out to the beet farms.

Pat: She talked some about it. My husband probably knows more, because he’s always been interested in what Mom and Dad talked about.

JM: What was your mother like?

Pat: She was a hard worker. She had 10 kids. She was able to take care of us and put food on the table no matter what. And she was always happy. Mom and Dad had a lot of friends, and they danced a lot.

JM: How well off were you when you were growing up?

Pat: We weren’t a very wealthy family, not with all of us kids. But we lived on the farm, so we always had food on the table.

Gerhard: My wife’s family history is interesting, because the Rommels were Germans who lived in Russia. A lot of the information we have about the family is written in the German language, and I speak and read German. Are you familiar with the history of the Germans from Russia, or the Volga-Deutsch, as they are called?

JM: No.

Gerhard: There’s a guy in Fort Collins that’s done quite a bit of research at the university. There were a bunch of German people that lived in Russia, near the Volga River. Catherine the Great had opened the country to them. Many of these people left Russia and went to the United States in late 1800s and early 1900s. When they came over, people here called them Russians, because they were born in Russia, although these people never spoke the Russian language. They had their own little agricultural towns over there.

A lot of them went to Kansas, towns like Victoria, Russell and Ellis. These little towns in Kansas were started by the Volga-Deutsch, these Germans from Russia. A lot of them moved later into Eastern Colorado to work in the sugar beet business. They raised sugar beets. Jacob Rommel used to farm about 40 acres. It was about 15 miles from their house in Fort Collins. That’s why they built those shacks out there, so they could stay in them. They were sharecroppers. They would get a percentage of the beet crop. They couldn’t afford to hire laborers, so the whole family helped. They would dig up the beets. They had to get them out of the ground before November or December, before they froze in the ground.

So the Rommel kids were actually helping the family. They weren’t going out and making money and bringing it home. They would dig the beets up, take the tops off, pile them, and then come back with pitchforks and a wagon and put them on a wagon. Then they would take them to a prearranged place where they would dump them, and then someone would come with railroad cars and take them to the sugar factory. Since the sugar factory in Fort Collins was probably only six or seven miles away, it’s possible that Jacob got a cart and some horses and took them to the sugar factory himself. They also had jobs at the sugar factory, and that’s how they made money through the winter months.

JM: Did the kids work in the sugar factories in the winter?

Gerhard: No, because they had their chores to do. They had chickens and cows, and had to do milking and things like that.

JM: Would they have gone to school then?

Gerhard: Yes. And they were very active in the church. They would read the bible and stuff like that. They were Lutheran.

JM: It’s interesting that you mentioned about them being Germans inside of Russia. Hine notes in the caption that one of the girls said, ‘Don’t call us Russians, we’re Germans.’

Gerhard: People over here would say, ‘You were born in Russia, so you are a Russian.’ But they did not want to be associated with Russians, because to them, a Russian was a bad person. There were lots of fights about it. I remember Martha saying, ‘I pulled out a girl’s hair once because she called me a dirty Russian.’

JM: Would you say that the Jacob Rommel family was better off than other families doing the same thing? They owned a little house, and they did other work during the winter, so it seems like he might have been a bit better off than some of the other sharecroppers.

Gerhard: No, I think they were all in the same boat.

JM: Is their house in Fort Collins still there?

Gerhard: Yes, but it’s been remodeled. There are big trees growing all around it, and there are lots of other houses there. It’s a nice old neighborhood. A lot of the old houses were built square, with a chimney in the middle. They put the stove in the middle and the rooms all the way around. That way they could get the heat to all the rooms.

JM: Lewis Hine was on a crusade to get the laws changed so that kids could go to school and not have to work all the time. Do you think these pictures of your wife’s ancestors were a good example for Hine to use?

Gerhard: Well, this was their culture. They were raised that way in Russia. The Germans had an old saying, ‘Work makes life sweet.’ They were farmers. They got up early in the morning, they worked hard, and they took pride in their work. They would challenge each other to see who could pick up a 100-pound sack of potatoes with their teeth, and that kind of stuff. If Jacob had been lucky enough to have some boys, he would have expected that they were going to take over the farm someday, and that the girls were going to eventually marry farmers, and then they would leave.

So I don’t think we can say that these kids were like the kids that had to work in the coal mines. The families worked these kids, but they didn’t work all the time. I’ve seen old pictures of farm families with the sons out in the field, but the girls were not out there. But Jacob, this poor guy, had no sons, and he needed help to get the beets out of the ground, so he had to use his daughters. If you understand their history and background, where they came from, and read their songs and their letters, this was just something they did then.

All photos provided by Rommel family, except where noted. Alice, who is in some of these pictures, was an older child who did not appear in the Hine photo.

*Story published in 2009.