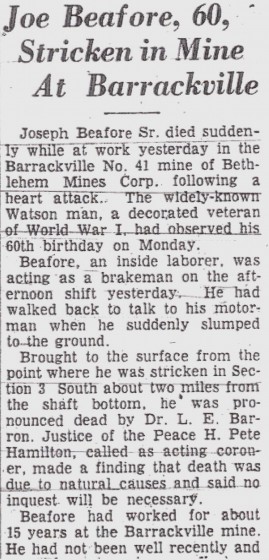

Lewis Hine caption: Monongah Glass Co., Fairmont, W. Va. Jo Before a glass wks boy going home, 5 P.M. He says he is 12 years old, and has been at it one year: is a “ketchin-up-boy” $.70 a day: says glass business is all right. Asked if he was going to be a glassblower when he grows up, he said “Sure!” Goes to school during school term: asked is [sic] he had to, he answered “Don’t unless I want to” asked why he went then, said “Want to learns something.” October 1908. Location: Fairmont, West Virginia.

“December 27, 1905: Dominick Beafore, New England Mine, left his place of work at 12:00 o’clock and rode to the outside of the mine to get his dinner. Upon returning to his work he got on front end of mine locomotive, and upon reaching a cross-over of main heading he jumped from the motor, of his own accord, evidently intending to throw switch. In so doing, he in some manner fell on the track and was run over by the motor. – Annual Report, Coal Mines in the State of West Virginia, 1906

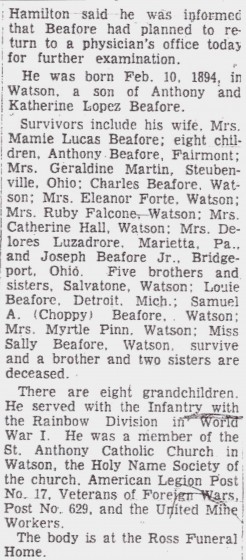

Dominick was one of Joe’s older brothers. When Joe grew up, he also worked in a coal mine. When this photo was taken, Joe was only 10 years old. At the time, the child labor laws in West Virginia allowed the employment of children 12 and over, with no limitation on hours. So it is likely that Joe’s parents lied about his age and the employer was complicit. As documented by the National Child Labor Committee investigators such as Charles Chute, the boys in the glass factories were subjected to intense heat and unrelenting, high-pressure physical activity that often resulted in dehydration and dangerous exposure to glass dust.

The Monongah Glass Company started in Fairmont in 1902. It produced pressed and blown glassware, and was one of the first glass companies to use machinery for mass production. By 1928, they were one of the largest glass factories in the United States. That year, they were purchased by the Hocking Glass Company.

Lewis Hine caption: 5 P.M. Boys going home from Monougal (Monongah) Glass Works. A native remarked “De place is lousey wid kids.” Location: Fairmont, West Virginia. October 1908.

Researching this family was difficult. There are many spellings of Beafore in government records. But I finally found most of what I wanted in the census, and in birth, marriage and death records. That led me to several descendants.

Joe (some records say Joseph) Beafore was born in Watson, West Virginia, on February 10, 1898. Watson is in Marion County, and is actually a village in Fairmont. His parents were Tony (probably Antonio) and Katherine (Lopez) Beafore, who married about 1890, and came to the US from Italy in about 1897. I could not find them in the 1900 census, or in immigration records.

In the 1910 census, the family is listed as living in Grant District, which is actually the name of the voting district in Watson. Mr. and Mrs. Beafore had eight children living with them; five others had died. Tony was a coal tipple, a worker who pushed carts of coal to an unloading area and “tipped” them over to dump out the coal. His two oldest children (19 and 17) also worked in the mine, and Joe still worked at the glass factory.

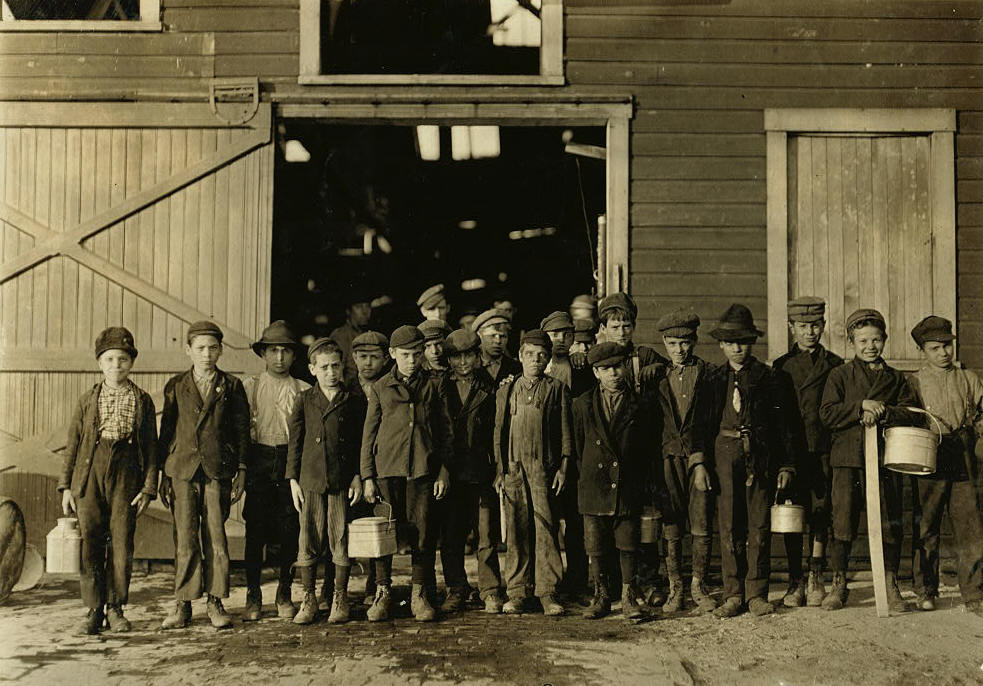

In the 1920 census, Joe is listed as living with his wife, Mamie, still in Watson. They lived next door (and likely rented from) his parents, who owned their house. Both Joe and his father Tony worked at the coal mine. He and Mamie (Lucas) married on December 4, 1919. In the 1930 census, they were still living in Grant and already had six children. Joe’s father died five years later, his mother not until 1949.

I tracked down a grandson, Anthony Beafore, simply by calling numerous Beafore households listed in the Fairmont phone directory. Mr. Beafore was surprised about the photo and pleased that I mailed him a copy. But he remembered nothing much about him, having been only four years old when Joe passed away. But he did send me a picture of Joe.

I also found Giovanna Clayton, one of Joe’s nieces. She told me that he served in WWI.

“He was shot in the foot and lost some of his toes. He was pretty disabled by it, but he still worked. He walked with a limp. When he would get a new pair of shoes, my dad, who was one of Joe’s younger brothers, would wear them for a while to break them in for Uncle Joe.”

Finally I found another grandson, Angelo Hall, who was born in 1947. He was raised by Joe and Mamie, who were his mother’s parents.

“I was only two weeks old when he took me in. I was born premature. I only weighed about a pound. My mom couldn’t take care of me. After that, he didn’t want to give me up, so I stayed with him. It was okay with my mom. She lived just a couple of houses away. I saw her all the time. I was only 10 years old when Joe died. From then on, my grandmother raised me. I was the only child in the home. All of their kids were already grown and out on their own. My grandmother did housework for other people so she could pay the bills and take care of me.”

Less than a year before the Hine photo was taken, there was a series of explosions at a coal mine in the nearby town of Monongah. According to one newspaper report: “The explosions ripped through the mines, causing the earth to shake as far as eight miles away, shattering buildings and pavement, hurling people and horses violently to the ground, and knocking streetcars off their rails.”

The explosions killed 362 men and boys. It remains the worst mine disaster in the history of the United States. In 1916, an explosion at a mine owned by the Bethlehem Mines Corporation, in Barrackville (near Fairmont), killed 10 workers. And in 1925, another accident in the same mine killed 33 workers. That is the mine where Joe was working when he died on February 11, 1958, at the age of 60. He had a heart attack while on the job. His wife Mamie died in 1985.

Letter from Genny Hall, wife of Joe Beafore’s grandson, Angelo Hall

“My husband Angelo was raised by Joe and Mamie. He is the oldest grandson. He made his life with Joe until the age of 10 ½, when Joe died suddenly. Grandpap Joe called my husband Angelo, even though his birth name was William S. Hall. Joe and Mamie attempted numerous times to officially adopt him, but they were never granted permission.”

“Mamie had a nervous breakdown after Joe’s death, and she and Angelo moved in with one of Joe’s daughters, Eleanor, for a couple of years, before returning to the family home. Angelo and I and our two daughters live in Watson, just a stone’s throw away from the house Angelo was raised in. The home remains pretty much the same. When Joe and Mamie purchased it, it was part of the mining camp. Our home is also one of the camp homes.”

“Grandpap Joe always had a dog, and loved animals. He was a very small man, about 5′ 4″. He worked long hours, and he and Mamie were rather poor. Most people were in those days, and owed most of their paychecks to the company store. The site of that store is about a block from the family home. Joe and Mamie had a big garden and canned everything they could. They also had a chicken coup in the yard that supplied eggs and many meals. As far as we can tell, Joe and Mamie had nine children, one of which died in infancy.”

“Joe was well liked and well respected in the area. When he died, the body lay in state at the home for two days. Angelo remembers the many friends and neighbors who came. Some sat with the body around the clock during those two days. The funeral log lists over 100 people.”

*Story published in 2010.