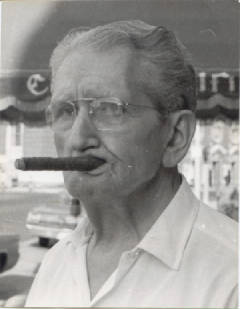

Lewis Hine caption: Joseph Crapo, 47 Fruit St. Works in Eclipse Mills. Apparently 13 years old. Location: North Adams, Massachusetts, August 1911.

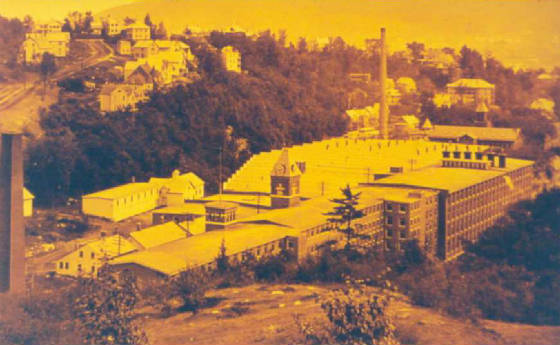

When this handsome young man posed for Lewis Hine almost 100 years ago, neither he nor anyone else in this small factory city in the Berkshires would have imagined that the Eclipse Mill would one day become well-appointed housing for artists. In 2005, the larger of the two remaining brick buildings in the mill complex (not visible here) along the Hoosic River was renovated into condominiums with studios and loft spaces, establishing itself as one of the prime factors in an ongoing attempt to convert North Adams from a declining manufacturing center into a destination for cultural tourism, and an ex-urban living environment friendly to the so-called creative class.

When Joseph met up with the investigative photographer while standing on what used to be the trolley tracks on Union Street, he was probably thinking about going home to his house across the river on Front Street (not Fruit Street, as Hine stated).

Lewis Hine caption: Joseph Crapo, 47 Fruit St., works in Eclipse Mills. Apparently 13 years old. Right hand. Left hand, Albert Duquette, 183 Union St. works in weave shed, putting drop wires on weave machine. Location: North Adams, Massachusetts, August 1911.

When I first saw the nine photos Hine took at the Eclipse Mill (including a few of Joseph), I was just starting my research project, and I was still learning the tricks of the trade. I was unfamiliar with the Soundex feature of the US Census, so when I looked for Joseph Crapo, I limited my search to the exact spelling. No one by that name turned up.

I had written two books about the history of North Adams, which is just an hour from my home. So I know the area well and have easy access to an array of historical documents. The North Adams Public Library has a complete collection of city directories going back more than 100 years, so I tried there. In 1917, a Joe Crapo was listed as living at 28 Bank Street, and working at Arnold Print Works, a huge textile mill that was located downtown, and is now the home of the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art. But starting the next year, he disappeared from the directories. On a hunch, I went to the city clerk’s office to see if I could find a death record and was shocked to discover that he died on February 20, 1918.

I returned to the library and found his obituary in the microfilm archives of the North Adams Transcript. The obit included the names of his widow and three surviving daughters. A considerable portion of it recounted his accomplishments as a well-known New England professional baseball player. He died of complications following surgery. The article image was of poor quality and very hard to read, but his age at death appeared to be 22, which meant that he would have been about 15 when Hine took the picture, not 12. Thus began a long search for living descendants, and ultimately one of the great wild goose chases of the Lewis Hine Project.

After finding his wife’s death record and obituary (1952), I was on the trail, and eventually tracked down the son of one of Joe’s daughters. By that time, I had collected a fair amount of family history about the Crapos, and offered to send copies to him. He was thrilled, since he knew very little about his ancestors. A week after I mailed it, I called him, and was stunned to learn that I had the wrong family, and the wrong Joe Crapo. He told me that his grandfather was born in 1886, and that he was 32 when he died, not 22. He said, “Sorry about the disappointing news, but thanks so much for putting together some of my family history. Good luck with your search.”

Lewis Hine caption: On right hand is Richard Fitzgerald, 53 Montgomery St., works in twisting room of Eclipse Mills, No. Adams. On left hand, Joseph Adams, 107 Front St., works in twisting room of Eclipse Mills,. Location: North Adams, Massachusetts, August 1911.

I went back to the census, this time using Soundex, and found a family named Crepeau living in North Adams in 1910, but no child named Joseph. But I did find a WWI draft registration for Joseph Idas Crepeau, born in 1898, and living at 47 Front Street with the same family. He was working for the Boston & Maine Railroad. Pretty soon, I found an Idas J. Crepeau, a barber at the Devens Hotel, in the 1923 Greenfield, Massachusetts town directory, which is online in Ancestry.com. In 1924, his brother, Alphege H. Crepeau, was also listed as a barber in Greenfield.

I drove up to Greenfield one morning and started snooping around, like a missing persons detective. On a lark, I walked into a senior center and found a group of elderly men sitting in the lounge drinking coffee and shooting the bull. I introduced myself and asked if any of them remembered any barbers named Crepeau. One of them spoke up right away: “Sure, Al and Paul. They were brothers, but they didn’t get along very well. Paul used to cut my hair when I was a little kid. I think he moved to Boston in the ‘30s.”

I headed over to the library and poured through town directories. In 1921, there was a Paul Crepeau, who was listed as a barber. At that point, I had to assume that Paul, Idas J., and Joseph Idas were the same person. I found brother Alphege, married to Lea, listed all the way through 1935. In several of those years, his first name was spelled Elphege. But in the next available directory, 1939, he is suddenly listed as Joseph E. Crepeau, same wife, same address, same barbershop. I thought, “So now he’s Joseph Crepeau, but his brother Joseph is called Paul. Did they do this just to trip up historians like me?”

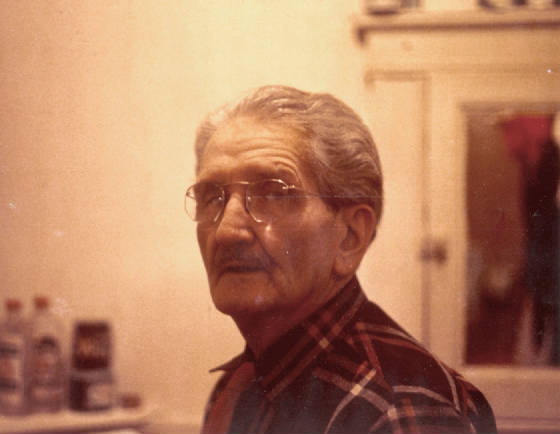

Over at City Hall, I found the 1990 death record for Joseph E (aka Alphege H.) Crepeau. He was 95 years old. I guessed that the “E” stood for Elphege. Back at the library, I found his obituary. He was born in Quebec, and after living in North Adams, moved to Greenfield in 1924, and was a self-employed barber until he retired in 1968. There was nothing to clear up the mystery about his name.

Back on the Internet, I found Paul Crepeau in the Massachusetts Death Index. He was born November 15, 1898, and died in Boston on July 6, 1992, at age 93. But in the Social Security Death Index, I found him listed as Idas J. Crepeau, with the same date of birth and death. I wondered if there were any more twists and turns — and alternative names — coming up.

It got easy after that. I found a descendant living in Berkshire County who connected me to Paul’s (Idas Joseph, et al.) only child, Rita Brown. When I called her, she had no idea about the Hine photos of her father. She told me that she had very little contact with him.

Idas Joseph Crepeau was born in Quebec, the son of Hormidas and Emelie Crepeau. According to the 1901 Canada census, his father was a farmer. As if to confuse things even more, Idas was listed as Hiledas (he was later listed for several years as Eledas in the North Adams city directories). Both the 1910 and 1920 census stated that the Crepeaus came to the US in 1910, a year before Hine took the photos, and that most of the children worked in the mill at that time.

The neighborhood around the Eclipse Mill was populated almost entirely by French-Canadian immigrants. Many lived on Front Street, a short, dead-end street susceptible to serious floods until the 1950s, when the Army Corps of Engineers installed flood chutes. The Crepeau house survived, although it’s obviously been remodeled and expanded.

Interview with Rita Brown (RB), daughter of Idas Joseph (Paul) Crepeau. Conducted by Joe Manning (JM), on November 29, 2006. Transcribed by Seunghee Cha and edited by Manning.

JM: What did you think of the picture of your father? Have you ever seen a picture of your father at that age?

RB: No. In fact, I didn’t know anything about him working as a child. And I’m sure my mother didn’t know anything about it either. But I guess that’s what happened back then. He only went to fourth grade because he didn’t know English.

JM: Did you know that his full name was Idas Joseph Crepeau?

RB: Yes.

JM: How come your dad was called Paul?

RB: I think that was his confirmation name. Neither one of my parents went by their real name, so it wasn’t odd to me. My mother was Alice Mildred Smith, but she went by Dorothy. She took that name when she converted to Catholic. She converted when I was about two.

JM: When did you mother and father get married?

RB: Around March of 1944.

JM: When were you born?

RB: April, 28, 1944. My mother left my father when I was four. He used to come up to visit every couple of weeks after that. He was drinking then, so it wasn’t too good. Then once I got in high school, I saw him maybe twice a year. I was living in Athol (Massachusetts) then.

JM: Why did he come over to visit?

RB: I think he came up to harass us. When we went to church, he wouldn’t wear his teeth. I hated that. And he used to make me kiss the Blessed Virgin’s feet in the snow.

JM: Was he being mean, or was he just an oddball?

RB: An extreme oddball. But now that I know that he worked as a child like that, perhaps he was acting like a big shot because he actually felt just the opposite. He didn’t have any friends. I went to Boston one time to visit him. I was an adult then, and had my children with me. He was managing the Prudential Center barber shop. It was on a Sunday, and there was hardly anyone in there, except a friend of his. He stood there and talked to his friend for a few minutes, but he never introduced me to him or anything. He never said, ‘This is my daughter.’ I thought that was very odd. He was like that. He didn’t want anybody to know his business.

JM: Did he have a good reputation as a barber?

RB: I think he was an excellent barber. He used to brag that he never used clippers; he always used scissors.

JM: Did you know that he started out as a barber in North Adams when he was a teenager?

RB: No. I know he wanted to be a surgeon at one time, but he didn’t have any education. He used to do feet too. He used to do my mother’s feet. She couldn’t stand him, but she said there wasn’t anyone who could get the corns off her feet like him. I had one on my foot as a child, and it hurt getting it out, but he cut that sucker right out.

JM: When your mother and father broke up, was it because he was drinking?

RB: When he drank too much, he would be out of control. But he was like a periodic alcoholic. He would go sober for a month and then he’d go on a toot for six weeks. When I was little my mother would go to Athol in the summer to visit her mother and work there, so she’d have some money. When I was four, at the end of the summer, I told my mother I didn’t want to go home. So she knew it was time to, you know, exit from the marriage. So my aunt from New Hampshire came and took us. We sneaked off while he was at work.

JM: When was the last time you saw him?

RB: He was in a rest home in Roxbury (Mass). They had asked me to cut his hair, because his hair was down to his shoulders. He looked like an Indian. It was parted in the middle and stuff. When I walked in, the first thing he said was, ‘Why in the hell don’t you get a haircut?’ He always needled me about my hair.

JM: Did you have any affection for him?

RB: Not really. But my mother made me respect him. If I started to say something bad, she would say, ‘You don’t talk about him that way; he’s still your father.’ And she never badmouthed him to me. She never called him a rotten husband, which he was. From the time I was two, I remember him cussing and swearing and breaking things in the apartment and stuff. When I got married, I asked him if he would give me away, and he said he was booked up with appointments that day. So he didn’t. But he showed up that night to visit my mother. He told her he thought she might be lonely. My aunt threw him out. I was working in a drugstore for awhile, and he would come in sometimes, get everybody to wait on him, and then he would tip them.

JM: So he was playing the big shot?

RB: Oh, yeah. They’d say to my mother: ‘Oh, he’s such a nice man. We don’t know why you two didn’t make it.’

JM: Did you live most of your childhood life in Athol?

RB: Yes.

JM: Did you go to his funeral?

RB: No. That was another thing. First of all, he got hit by a Boston Edison truck. He was going to sue, but he didn’t trust any lawyers, so he ended up with like $3,000, which just about paid the medical bills. And it took him three months for him to even say that he had a daughter, and for them to find me. When he was in rehab, I went up to see him. He was able to speak and walk at that time. But then he decided to just get in bed and give up. This was when he was 79. He stayed in bed until he was 93. The doctor called and said that his cancer had returned and they needed to do the dialysis, and he asked me what he should do. I asked the doctor, ‘What did my father say?’ And he said, ‘If you can’t cure me, don’t do it.’ And I said, ‘Well, I don’t believe in prolonging death.’ And the doctor said, ‘You wouldn’t know him; he’s half the man that you knew.’

So then Hospice got involved. I talked to their minister, who was a lady, and told her the situation and how he treated me every time I saw him. I said, ‘I just can’t come to see him. I feel horribly guilty, but I don’t want to see him.’ So they suggested I write him a letter. So I did. I had a good cry, and then I mailed it. I guess he let them read about half of it, and then he told them, ‘Stop, I don’t want to hear any more.’ Basically, I just told him that I didn’t hold him responsible for anything and that my mother did a good job raising me. I kind of let him off the hook. But he didn’t want to hear it.

I had him cremated. He was supposed to be buried in a family lot in North Adams, but there was no room for him. So the guy at the funeral home said, ‘If you want to cremate him, we can make room in the family plot.’ So that’s what they did, but I don’t know where the plot is. Somewhere in North Adams, I guess.

JM: Did you know that when he left North Adams, he went to Greenfield? I found him in the Greenfield city directory. He was a barber in a hotel.

RB: That sounds like him.

JM: And then he was in partnership with his brother Al.

RB: Yeah, but there was conflict between them.

JM: I went into the senior center in Greenfield looking for people who might remember Al and your father. I met an old guy who was sitting around just talking, and he said: ‘Oh yeah, Al and Paul used to cut my hair when I was a kid. Then Paul left and Al stayed.’

RB: I used to go with my mother to get school clothes in Greenfield. My mother walked by the barbershop and said, ‘That’s your uncle Al in there. Why don’t you go in and say hello to him?’ I was probably about 13. So I went in and said, ‘Hi, I’m Paul’s daughter.’ And he just looked at me and said, ‘You’ll have to stop in again when you’re around.’ I told my mother, and she said, ‘What a jerk.’

JM: Lewis Hine took nine pictures on that day. He apparently couldn’t get in the mill, so he took the pictures outside of the mill, or in some cases he took pictures of them in front of their houses. And in eight of those nine pictures, your father was in them.

RB: That figures.

JM: He looked like he knew how to pose for a picture.

RB: I’m sure he did. That sounds like him. I wished I had kept the copy of the will for you. That was interesting. My mother said that when he was about 16, he wanted to take his sister Jeannette to the dance. His father said no. So he and his father had a physical fight, and he had his father down on the floor, and he said he was going to kill him. His mother broke it up. And supposedly they never spoke again. When his father died, he left my father one dollar in the will. But my mother said that my father idolized his mother. His mother used to say, ‘Don’t buy me flowers when I’m dead; buy me strawberry ice cream while I’m alive.’ She said he really loved his mother and hated his dad. And my mother always told me – and I know she got this from my dad — that he was one of 16 children, but only five lived to be adults.

JM: I think that picture of him by himself with his hat on is amazing. It reminds me of a very famous poster of James Dean, the actor, walking down the street smoking a cigarette. Your father was very handsome in that picture.

RB: My mother always said he was really good looking, and that he was a wonderful dancer. But she told me, ‘Pick out a guy that’s ugly, because nobody else will want him.’ I didn’t realize until I saw that picture of him at the mill that perhaps this was why he was like he was. I think he smacked me once. I know that when my mother left him, he told her that if anything ever happened to me, he’d kill her. They didn’t actually get a divorce until I was 13. I said to my mother, ‘You need to get rid of him.’ So she filed papers and he came over and said to me, ‘Your mother filed papers. What do you want me to do?’ And I said ‘Get a divorce.’ My mother never remarried. She said once around was enough.

“Paul (Crepeau) was quite a dancer, wore tailor-made, tight bell-bottom pants with a sewed-in crease. I was happy when old Pefferle beat him for $10 in a foot race on Main Street. Paul, having had a few drinks, challenged Pefferle to the foot race. He was old, but he beat Paul.” -Edward “Duke” Duhaime, who, in the 1950s, wrote about his memories of Greenfield. Reprinted by permission of the Greenfield Recorder.

*Story published in 2009.