Lewis Hine caption: Joe Allard, 5 Tannery Yard (on left hand). Sweeper in twisting room, Eclipse Mills. Location: North Adams, Massachusetts, August 1911.

“Every New Year’s Eve, my father would take each one of us kids into a room alone, and we’d get down on our knees, and he would give us a New Year’s blessing. You just don’t forget things like that. He was a great man. -Rolland Allard, son of Joseph Allard

There are two interesting twists to this story. First of all, many visitors to my website know that I have written two books about the history of North Adams, and that I have been visiting the city about once week for the past 13 years. It’s about an hour’s drive from my home. I have no previous ties to the community. I have made many friends there. Thus, it was quite a surprise to me that when I tracked down Joseph Allard’s youngest son, it turned out to be a friend, Rolland Allard, with whom I have had many conversations over breakfast at one of the North Adams coffee shops. He moved several years ago to Colorado, so it was good to reconnect. He was very touched by the Hine photo of his father.

The other twist to this story could be summed up by the question: “Which boy in the photo is Joseph?” Hine claimed he was the boy on the left, but Rolland is sure his father is the boy who is 2nd from the right. Joseph Allard’s name appears in the caption of another Hine photo (see below). It appears that Hine is referring to the boy standing with his arms folded. He looks like the same boy that Hine identifies as Joseph in the top photo.

It was not uncommon for Hine to make mistakes in his identification of children. In some cases, he misspelled names so badly that there is no hope of figuring out the correct name. In other cases, he mentioned a name in the caption but did not point out which child had that name. And there are examples where he attributed a name to the wrong child. So it is entirely possible that Hine identified the wrong boy as Joseph Allard.

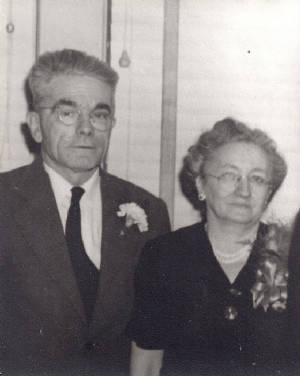

Records clearly establish that he was 19 years old at the time of the photo. Rolland told me that his father was very short, only about 5′ 4″ as an adult. On his WWI draft registration, he is listed as “short.” The boy Hine called Joseph Allard looks much younger than 19 in the photo at the bottom. And in the other photo, he looks quite tall. The boy Rolland identifies as his father looks like he could be 19 years old. I studied family photos Rolland sent me of Joseph as an adult, several with many of his children. He, quite convincingly, looks like the boy Rolland says is his father, and very little at all like the boy Hine identified as Joseph. I asked myself, “Who am I to question his son?” Finally, I talked to a friend in North Adams, now 86 years old, who worked with several members of the Allard family back in the 1940s. He looked at the boy that Rolland identified as his father and told me that he looked just like Joseph Allard’s son Joe.

Lewis Hine caption: Joe Allard, 5 Tannery Yard. Sweeper in twisting room, Eclipse Mills, No. Adams. Location: North Adams, Massachusetts, August 1911.

Joseph’s son, Rolland, thinks the boy with the white shirt who is sprawled on the landing is his father.

Since Joe was 19 when Hine photographed him, he was hardly a child laborer. He was simply identified in several photos where some of the others pictured were under the legal age of 14, which was the law in Massachusetts at the time. Given the times, Joe could very well have been working at the mill for more than five years. The area called Tannery Yard, where Allard lived, was about 200 feet west of the Barber Leather Mill, which has since been partially demolished. The mill housing that he lived in was along the Hoosic River, and was torn down in the 1960s. It’s just a vacant lot now with scrubby trees and underbrush along the river, which is now a flood chute built by the Army Corps of Engineers. The area experienced a devastating flood in 1927. To see more information about the Eclipse Mill, see the links at the end of this story.

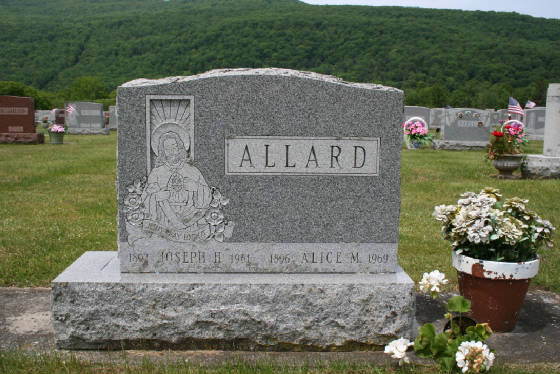

Joseph Hector Allard was born in St. Hyacinthe, Quebec, on March 31, 1892. His parents were Alfred and Caroline Allard. They appear in the 1901 Canada census with five children, Joseph being the third oldest. Alfred’s occupation is listed as chef. There is no record of their entry into the US, though Joseph’s obituary lists the year as 1901. In 1910, Alfred is married to Antonia, who is listed as his third wife. He is a blacksmith, but in the 1920 and 1930 censuses, he is listed as a carpenter. Joseph married Alice Moreau about 1914. He passed away on December 9, 1961, at the age of 69. Alice died in 1969.

Edited interview with Rolland Allard (RA), son of Joseph Allard. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on September 9, 2009.

JM: What did you think of the photos of your father?

RA: The pictures were very heartwarming. I have some pictures of him, but nothing that goes that far back. I knew he worked in the mill. He worked his way up to a supervisor eventually. When the cotton mill closed (Hoosac Cotton Mill), he became a self-employed carpenter and handyman. He knew a lot about building homes and remodeling. At one time, he was working for a company in Williamstown, and he was putting two spikes in the two-by-fours, and the company owner told him not to do that. So rather than changing the way he was doing it, my father quit. That’s how independent he was. He wanted things to be done right.

JM: How tall was he?

RA: Only about 5′ 4″.

JM: When did your parents marry?

RA: About 1914 or so.

JM: Did your mother work outside the home.

RA: No, she was a homebody.

JM: How many children did they have?

RA: There were 14 of us. Two boys died at birth. The only two left are me and my brother Joe. I was the baby, the youngest. I was born in 1938.

JM: Where was your family living when you were born?

RA: We were living in a house in Clarksburg (borders North Adams). When my father bought it, it was just a little camp (cabin). He added some rooms to it.

JM: On your father’s WWII draft registration, he listed his address as 415 Walker Street.

RA: Yes, that’s the address.

JM: He also listed his employer as the Strong-Hewat woolen mill.

RA: I don’t remember that; I just know that he worked in the mills.

JM: In the 1954 city directory, he is listed at 390 Walker Street.

RA: Yes. He sold the first house and bought that one. It was much more modern. It had indoor plumbing, which we didn’t have in the other house. He worked most of the time, but when he was needed at home, he was there. We owned a good 15 to 20 acres there. We had a big garden. We grew our own vegetables. We had some chickens and a couple of cows for milking. That’s how we survived.

JM: In the 1959 directory, he is living at 23 Irving Avenue, in North Adams.

RA: Yes. One of my sisters and her husband owned it. He sold the house at 390 Walker to my brother Connie. By that time, my father was getting up there in years. In fact, my sister wanted to take his driver’s license away. He drove her to work one day, and he hit a telephone pole. Eventually, he gave up driving. I moved to California around that time. When I came back home, they were living in Briggsville (village in Clarksburg).

JM: The 1910 census lists your grandfather, Alfred Allard, with his wife and four children, including your father, who was working in a cotton mill. He was 18 then. The family is living at 5 Tannery Yard. Your grandfather was running a blacksmith shop, and this was his third marriage.

RA: Yes, I guess he got around quite a bit.

JM: What do you think about the fact that Hine was exposing child labor and your father was photographed as an example? In this case, Hine wouldn’t have had a problem with your father being 19 years old, but I imagine he figured your father had worked there quite a while, so he would have worked there when he was much younger.

RA: Let’s face it; those were the days of the sweatshops. This is something that men and boys had to do to survive. Can you imagine if there had been no sweatshops at that time, how many people wouldn’t have made it? It’s not that I am in favor of sweatshops, but I am saying this was basically a way of survival. These people wanted to work because they needed the money.

JM: How old were you when you first went to work?

RA: I’ve had 26 jobs in my lifetime. Being handicapped is not an easy thing when you’re trying to get a job. When they want to lay off people, the guy who’s handicapped is the first to go. And that still goes on today.

JM: What is your handicap?

RA: Being French. No, I’m just kidding. When I was nine years old, I got hit on the head, which gave me an aneurysm that broke. As a result, it left me paralyzed on my left side. Fortunately, I overcame a lot of it. My first job was playing Santa Claus at J.J. Newberry’s. I had jobs that go from working for Goodwill Industries to refinishing furniture to traveling across the country giving out free samples of Mr. Clean. I took those jobs to survive. Finally, I woke up one day and said to myself, ‘What a jerk you are.’ I finally went back to school and got some further education and got a job working for a small company, but when any company wants to get rid of a handicapped individual they give him or her a job that the company feels one can’t physically handle. I held on as long as I could, having a family to support. Eventually I had to retire on disability. (Note: Rolland Allard recently wrote and published a book about people dealing with disabilities. It’s called Unspoken Bias.)

JM: What was your father like?

RA: As far as I’m concerned, he could walk on water. You couldn’t find a more loving father, and a more loving mother. I thank them for giving me the tools to go further in life. My father would never take any grief from anybody. He wasn’t one to be pushed around. You meet any of us Allards, and you’ll see we’re all the same. We don’t mind giving and we don’t mind helping, but we protect ourselves and our family. I remember my dad coming home one day, and he was madder than heck. He went down to City Hall. They had made a penny mistake on his tax bill – one penny. He wanted that penny. They had to get a cop to get him out of there. That was my father. It runs in the family.

Being Catholic, my father saw to it that we all got down on our knees and said the Rosary the whole month of June. He made sure we did that. If we didn’t finish the Rosary, he would chase us upstairs to our bedroom, and we’d hide underneath the bed. He had a barber’s strap, but he never used it. He swung it at you to let you know he had it, and then he’d tell us to get downstairs and finish the Rosary.

I’ll tell you a heartwarming story. Every New Year’s Eve, my father would take each one of us kids into a room alone, and we’d get down on our knees, and he would give us a New Year’s blessing. You just don’t forget things like that. He was a great man.

*Story published in 2010.