Lewis Hine caption: Family of L.H. Kirkpatrick, Route 1, Lawton, Oklahoma. Children go to Mineral Wells School #39. Father, mother and five children (5, 6, 10, 11 and 12 years old) pick cotton. “We pick a bale in four days.” Dovey, 5 years old, picks 15 pounds a day (average) Mother said: “She jess works fer pleasure.” Ertle, 6 years, picks 20 pounds a day (average) Vonnnie, 10 years, picks 50 pounds a day (average) Edward, 11 years, picks 75 pounds a day (average) Otis, 12 years, picks 75 pounds a day (average) Expect to be out of school for two weeks more picking. Father is a renter. Works part of farm on shares (gives 1/4 of cotton for rent) and part of farm he pays cash rent. Location: Comanche County, Oklahoma / Lewis W. Hine, October 10, 1916.

“My grandfather died from diabetes. When he was in his early sixties, they had to cut his legs off. He accepted it as a part of his life. My grandparents took whatever came along and did their best with it, and stood up and faced whatever came along. They were good pioneer stock.” -Tommy Ray Kirkpatrick, grandson of Mr. and Mrs. L.H. Kirkpatrick, son of Ertle Kirkpatrick

The following is from Saga of An Okie, by Jesse Lee Wright (1907-1991), posted on Oklahoma GenWeb:

“I always loved the fall of the year, which meant no school till after Christmas, as all us kids had to turn out, get fitted with new cotton sacks, anywhere from 8 to 4 ft long, with shoulder straps to fit each kid, then out to the cotton fields to pick cotton. The way we got paid was about 10% of what the farmer received after he had the cotton ginned, like if he received 40 cents per lb the picker received $4.00 per 100 lbs.”

“The average picker can get 100-200 lbs per day. After I got to be 16-17 years old I was picking 500 lbs per day. The hardest work was hauling it to the scales. This took a little planning, like finding how much cotton it took to fill the bag and be as near the scales as possible. You wouldn’t want to get too far away with a full bag and have to lug it all the way back. We’d usually pick cotton till end of the year, then start school, with new shoes and clothes.”

“We lived mostly day to day, never sure where our next meal would come from, indeed we saw more meal times than meals.”

**************************

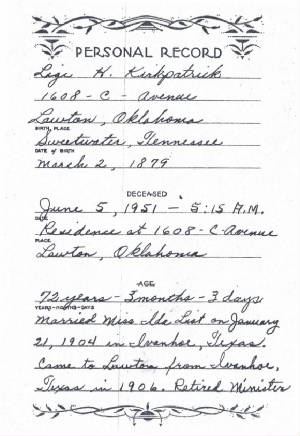

In the 1900 census, 20-year-old Elijah Holliman (called Lige) Kirkpatrick, a Tennessee native, was listed as living on a farm in Ivanhoe, Texas, an unincorporated village in Fannin County, with his parents and three siblings. The farm was rented, indicating that his parents were probably sharecroppers. According to genealogy records, he married Naomi Listz in 1904. Their first two children, Otis and Edward, were born in Fannin County; the next, Vonnie, in New Mexico. In 1910, he and Ida were sharecroppers in Lincoln Township, Oklahoma, just east of Lawton. They had five more children over the next dozen years: Ertle, Naomi (Dovey), Arvie, Frank, and Everett.

According to the Oklahoma Historical Society’s Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, the Oklahoma Territory (Oklahoma became a state in 1907) experienced a huge influx of white tenant farmers starting in the 1880s. From 1900 to 1910, the number of white tenant farmers doubled. These farmers had to give one third of their grain crop and one fourth of their cotton crop to the landlord, as well as shouldering the entire cost of animals and equipment.

The City of Lawton website tells us that the town was founded in 1901, when the last of the Indian lands in the Oklahoma Territory were opened by the federal government. There was a land lottery established, resulting in over 29,000 hopeful homesteaders traveling from all over the US to register at nearby Fort Sill. Only 6,500 were selected. Perhaps Lige Kirkpatrick was one of the unlucky ones, and had to rent farmland. He would have witnessed a community struggling with a land rush for which it was unprepared. There were about 25,000 people living in tents. There were no streets or sidewalks and no utilities. The schools were overcrowded, and the water supply was inadequate and unsanitary.

In 1916, Lewis Hine found the Kirkpatricks out in the cotton fields and took three pictures. He took hundreds of photographs of farm families, some that owned, and some that rented. It was not your typical child labor situation – no factory boss, no spinning machine, no faces covered with coal dust – but still not a road paved with opportunity, especially with the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl less than a generation away. It was a hard life, but one that the Kirkpatricks would somehow endure.

Lewis Hine caption: Family of L.H. Kirkpatrick, Route 1, Lawton, Okla. Children go to Mineral Wells School #39. Father, mother and five children (5, 6, 10, 11 and 12 years old) pick cotton. “We pick a bale in four days.” Dovey, 5 years old, picks 15 pounds a day (average) Mother said: “She jess works fer pleasure.” Ertle, 6 years, picks 20 pounds a day (average) Vonnnie, 10 years, picks 50 pounds a day (average) Edward, 11 years, picks 75 pounds a day (average) Otis, 12 years, picks 75 pounds a day (average) Expect to be out of school for two weeks more picking. Father is a renter. Works part of farm on shares (gives 1/4 of cotton for rent) and part of farm he pays cash rent. Location: Comanche County, Oklahoma / Lewis W. Hine, October 10, 1916.

I began my research by looking up Ertle. I found him immediately on a family history posting, which listed a son named Tommy Ray Kirkpatrick. I had no trouble finding him. He lives in Oklahoma. He was very surprised when I called him about the photos. I interviewed him shortly afterward.

Lewis Hine caption: Dovey Kirkpatrick, 5 years old, picks 15 pounds of cotton a day (average) Mother said: “She jess works fer pleasure.” Location: Comanche County, Oklahoma / Lewis W. Hine, October 10, 1916.

Edited interview with Tommy Ray Kirkpatrick (TK), son of Ertle Kirkpatrick. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on July 27, 2009.

JM: What was your reaction to the photograph? Were you surprised by what your father was doing at that age?

TK: Oh, no. They grew up poor. They were poor before the Depression, but the Depression really knocked them off their feet. They had to get out there and find out how to make a dollar.

JM: How did they do that?

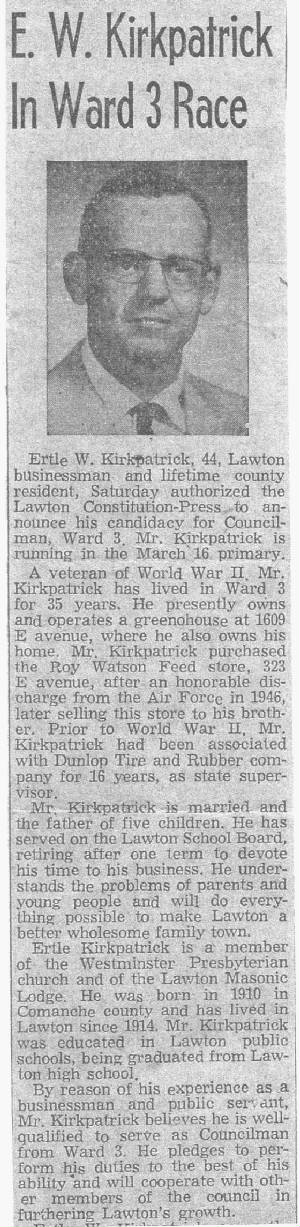

TK: For the most part, the boys didn’t finish school and had to work. My dad dropped out in the tenth grade and started selling tires at a tire store, Dunlop Tires in Lawton. He was working 10 hours a day, six days a week.

JM: When did he start doing that?

TK: He went to work at Dunlop Tire in 1931. He married my mother, Alice Lenore Wilson, also in 1931. As far as I know, my father was born in Comanche County, February 16, 1910. My mother was born on the same date in 1911. I was born in 1933.

JM: In the 1930 census, your father was listed as living with his parents and working as a laborer in a poultry house.

TK: I did a little bit of that myself. There was a place in Lawton where we bought chickens from the farmers, fryers primarily. And all day long they sit there, kill them, strip them down, gut them, and get them ready to go to market.

JM: How long was he with Dunlop Tire?

TK: He was still with them when he got drafted into WWII, about 1944, about a year before we defeated Germany. He used to tell everybody, ‘When Hitler found out that I was in the military, he decided to go ahead and surrender.’ He had a good sense of humor. When he came back, he bought a feed and seed store in Lawton. At that time, most people still had chickens in their back yard. And if they could afford it, they had a cow. And then things got better, supermarkets developed, and it was cheaper to buy your milk than it was to buy a cow, and it was cheaper to buy your eggs than to raise chickens. We still raised a few chickens and sold them. People would call my mother and order chickens that they wanted for dinner. She would call Daddy and tell him that when he came home at five o’clock, she would have some dead chickens in the back yard. She’d have the water hot, and he and I would strip their feathers, and he’d gut them, and she’d cut them up. By seven o’clock, people would come by to pick them up.

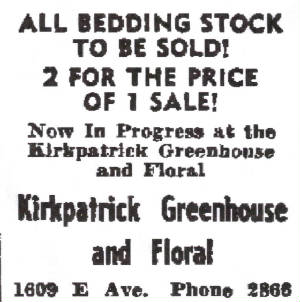

I got out of high school in 1951. At some point, he built my mother a small greenhouse so she could raise flowers. I went into the military in 1953. That’s about when he sold the feed store to my uncle, and he started growing tomato plants and pepper plants, by the thousands. He would pull them up when they were about an inch tall and replant them in individual containers, and he and my mother worked late at night doing that. He would go out the next morning with his truck and go around to supermarkets selling them.

JM: That must have been a very competitive business.

TK: It was, and it was very demanding. He was working seven days a week, and my mother was working, too. They were on their feet all day long, but they made some money out of it. Then Daddy sold that business and went into the floral business selling flowers for weddings and funerals and things like that. He made lots of money on Mother’s Day and other holidays. The rest of the time, he just tried to break even. During the spring, he still did his tomatoes and peppers, and he did alright.

TK: My father died when he was 88. Alzheimer’s got him. He had that for seven or eight years. My grandfather died from diabetes. When he was in his early sixties, they had to cut his legs off. He accepted it as a part of his life. My grandparents took whatever came along and did their best with it, and stood up and faced whatever came along. They were good pioneer stock.

JM: When did your mother die?

TK: In 1972. Cancer got her. She fought that for 10 or 12 years. Daddy retired at age 65, so he could take care of her. He would buy large houses, work them over again, make efficiency apartments out of them, and rent them to the military personnel.

JM: They lived near a military base?

TK: Yes, Fort Sill.

JM: Did your father ever talk about being on the farm when he was a boy?

TK: Not really.

JM: Did he ever talk about picking cotton?

TK: Yes, a little. I picked cotton once. I was with my grandpa. There was this little girl about 10 years old who was doing it, and I figured if she could do it, so could I. I was 14 then. My grandfather gave me a sack and said, ‘Go pick cotton while I do some business.’ After about 30 minutes, I was dead tired and I was trying to figure out how I was going to get out of it. Then he came over and told me he was going into town, and he wanted to know if I wanted to go with him. So I gave that girl what cotton I had picked.

My dad told me that in about 1922 or 1923, my grandparents moved into Lawton, in town proper, and they had a used furniture store. That was back when they had wood-burning cook stoves. He’d buy those and refurbish them and resell them out of his store.

JM: What about the famous dust storm in 1936? Did your father ever talk about that?

TK: No, he never said anything about it. Of course, I was too young to remember it. I was only three at the time.

JM: In the 1930 census, your grandfather was listed as a cement mixer, and your grandmother was listed as a seamstress in a tailor shop.

TK: I didn’t know that my grandfather did that. My grandmother did sew all of her life. Being there in a military town, these guys would get promoted and they’d want their stripes sewed on, so they’d come see her, and she would do it for about 10 cents a sleeve. When my grandfather died, they listed his occupation as a preacher. He didn’t belong to a church. I knew him as one who stood on the corner and tried to preach, but he couldn’t get anybody to listen to him. He only went to about the third grade, and then he had to go to work. During the World War II, he got patriotic and went out to Fort Sill to do some construction work. That lasted about a week, and he came home and told Grandma he’d find some other way to make a living.

JM: What was your father like?

TK: It’s kind of hard to say. He and I didn’t get along too well.

JM: Why?

TK: I never knew. He was tough. He didn’t talk to me much. It was just things like: ‘Hey boy, get that lawnmower,’ ‘Hey boy do this,’ ‘Hey boy, why don’t you do it better?’ I didn’t grow up with the standards that he grew up with. I didn’t have to work when I was real young. But I did work all the way through high school. I bought my own clothes starting when I was about 15. I had to, because I had four sisters.

JM: What was your grandmother like?

TK: She was sweet. She took care of me every once in a while. We lived a couple of blocks from her. I would come home from school and stop by her house for a drink of water and talk to her for a few minutes, and she’d fix me some peanut butter and crackers. Then I’d go on home and start mowing the lawn. When I got old enough, I had to catch the bus downtown. Daddy had the feed store down there, and I had to go there and work.

JM: One of the girls in the photo was identified as Dovey. In the 1930 census, she was listed as a telephone operator. Did you know her?

TK: Yes, Aunt Dovey. Her first name was Naomi. Her middle name was Dey. They called her Dovey. She married a Stephens and lived in Oklahoma until she divorced him. Then she married a guy named Tilley. She died in New Mexico, but I don’t know when.

JM: Did you go to college?

TK: I went in the military to get the GI Bill, and then I went to UCLA. That’s the University of Cameron in the Lawton area. Then I went to MIT. That’s Murray Junior College in Tishomingo (Oklahoma). I got my degree in accounting at Central State College, which is now Central University (Oklahoma).

JM: Did you get a job in accounting right after that?

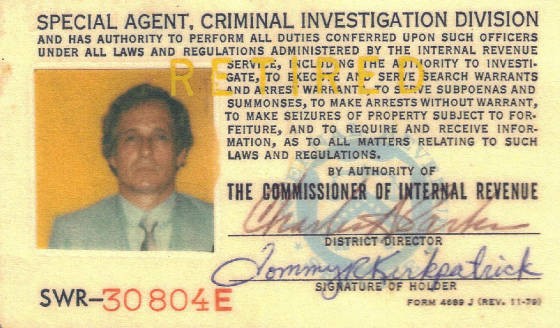

TK: No. I was keeping books for a trucking company, unhappily. Then I joined the Internal Revenue Service, and became a special agent with the criminal division. You’ve heard of Watergate? I was one of their investigators, but not for very long. There was a lot of leakage of information, so they didn’t want us to have much information. I worked for the IRS for 25 years. At age 51, my health had deteriorated to the point where they told me I wasn’t going to live much longer, so I retired. Here I am at 76 and still alive.

JM: What can you tell me about what you did in the Watergate investigation that I can repeat?

TK: Not much. I can tell you that we were looking for the source of $3 million that allegedly had been placed on the presidential plane in Guam. I was able to track down about $250,000 of it, and get some statements for the grand jury’s consideration. We had to change our focus. If you give money to a politician, you might consider it a bribe, but the politician might consider it just a political contribution. So we (Special Agents of the Criminal Division of the Internal Revenue Service) had to determine what was done with the money. I believe that the money was given to the president, and never applied by him to anything personal for himself. He apparently used the money to get re-elected, and I believe it was used in part to pay for the Watergate break-in. So it was not taxable income to the president, but it had been used for illegal activities.

JM: What do you think about the fact that Lewis Hine was using the photos of your family as an example of child labor?

TK: I think it was excellent that he did that.

JM: Do you feel sorry for your father that he had to do that at such a young age?

TK: Everybody else was doing the same thing. That was his attitude. He was poor, but he said that everybody he knew was poor. My grandfather was a sharecropper. He also went into business for himself buying and selling second hand furniture. My grandmother did sewing on the side. I can remember as a kid that her boys got together and bought her an electric washing machine. She set it up on her back porch and started washing clothes for her neighbors and hanging them out on the line, and getting paid for it. They had a little red wagon she used, so she could transport the clothes back to the people, and I always thought that was such a waste. It was a beautiful wagon, something that I could have played with, but she would not allow that. It was her business wagon.

I didn’t know there was an indoor toilet till I was eight years old. My grandparents didn’t have one. My dad bought some land two blocks south from my grandparents, paid it off a little at a time, and built a little four-room house on it and put an outhouse out on the back part of the lot. I used that till I was eight years old. Then he added a couple more rooms, including a toilet. I thought that was real nice.

JM: What was the address of that house?

TK: Let’s see now. I was born in my grandparents’ house, which was at 1608 C. Street, in Lawton. We lived in a rental property on D. Street while Daddy was building the house. Then we were on 1609 E. Street, which is the one that had the outhouse. When I was in high school, he decided to build a two-story house next door at 1611. When I got home from school, I didn’t want to get out there and work on that house, but he would start chewing my butt when he came home because I hadn’t gotten the drywall up or the sheetrock in. But I learned how to do a lot of things. I could even make mistakes. It was alright with him, as long as it was the first time I had done it. I couldn’t make the mistake twice, though. He grew up learning that you try it, and if it doesn’t work, you figure out why it doesn’t work, and then you make it work.

JM: In the 1930 census, the address of your grandparents’ house was listed as 1606 C. Street, not 1608.

TK: 1608 was the address of the Post Office. 1606 was a vacant property that my grandmother had acquired by trading a horse for it. Then the city came out and put the concrete streets in, so she sold the lot.

JM: Are those houses still there?

TK: No. My grandfather built the house I was born in. He had an old two-wheel pushcart, and whenever the city tore up a sidewalk or a street, he would go down and pick up the chunks of concrete and haul them off to his house and dump them. Whenever he could afford it, he’d buy a couple of sacks of cement, and he and some of his boys would get out there and cement those chunks together. They built a wall and a floor, and finally it was a solid concrete house, but it’s gone now.

Elijah Hollman “Lige” Kirkpatrick: 1880 – 1951.

Ida Naomi Kirkpatrick: 1884 – 1974.

Otis Adam Kirkpatrick: 1904 – 1970.

Edward Lee Kirkpatrick: 1906 – 1989.

Vonnie Clayton Kirkpatrick: 1908 – 1989.

Ertle William Kirkpatrick: 1910 – 1988.

Naomi “Dovey” Kirkpatrick: 1912 – 1989.

*Story published in 2010.