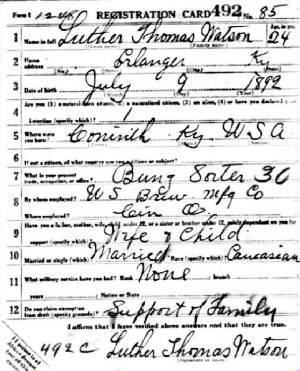

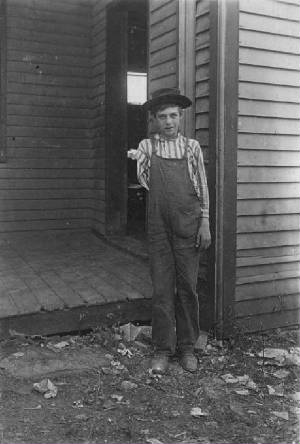

Lewis Hine caption: Luther Watson, of Corinth, KY, 14 years old, Dec. 30, 1906, right arm was cut off by a veneering saw in a box factory (in Cincinnati) on Nov. 14, 1907. He used a board to throp belt operating (saw as there) was no apparatus to do this. Now attending school. Mother intends to give him an education “so’s he won’t have to work.” Nov. 1907, Lewis Hine.

“He could do anything he wanted to. He had all his strength in that one arm. When I got married, he built a whole room underneath the house so we could live in it.” -Nola Blankenship, daughter of Luther Watson

According to an Ohio forestry pamphlet, published in the early 1900s, there were four bung factories in operation at that time in Cincinnati: American Bung Mfg. Co, National Bung Mfg Co, Queen City Bung Mfg, and United States Bung Mfg. Co. A bung is a device used to seal a container, such as a barrel. One of these companies, which also made boxes, employed a young man named Luther Watson, who lived across the Ohio River, in Kentucky.

In 1907, Lewis Hine was assigned to take photographs of life among industrial workers in Pittsburgh, for the Russell Sage Foundation. Because he did not begin his 32-state journey to photograph child labor until 1908, it is not clear why Hine would have been in Kentucky in 1907. The photo is in the collection at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, but does not appear in the Library of Congress collection obtained from the National Child Labor Committee.

When Luther Watson was injured, there were no workers’ compensation laws in the USA. The first compensation system in America was proposed by President Taft, and enacted in 1908, but applied only to companies involved in interstate trade. In 1911, the Ohio General Assembly passed the state’s first workers’ compensation law, although astonishingly, it was voluntary and funded by the state. So in 1907, Luther was forced to face life without one arm, and his parents were presumably saddled with the medical bills. No wonder Hine became such a passionate proponent of child labor laws, having witnessed this incident even before his celebrated work started.

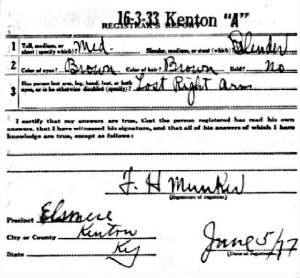

I found Luther in the 1920 census. He was living in Covington, Kentucky, with his wife and two girls. His occupation was listed as a telegraph messenger. In the 1930 census, he was listed as living in Elsmere, Kentucky, with two additional girls, and he was employed as a switch tender for the railroad. I also found his 1961 Kentucky death record, but I was unable to obtain his obituary.

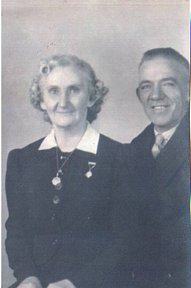

Since all his children were girls, and I didn’t know their married names, I was stumped as to how to locate any of his descendants. So I Googled him. Miraculously, I found a photograph of Luther on a website posted by his great-granddaughter, Lisa Hinkle. There he was, in 1938, standing with his wife and two grandchildren. He still had one arm.

I contacted Lisa and she led me to her grandmother, Luther’s daughter Nola, who had never seen Hine’s photograph.

Luther Thomas Watson was born on July 09, 1892, in Grant County, Kentucky. His parents were John and Lucy Powell Watson. He married Mabel Celia Freeman on April 18, 1914, in Ohio. Luther passed away on July 27, 1961, at the age of 69, and wife Mabel died on June 25, 1972, at the age of 75.

Edited interview with Nola Blankenship (NB), daughter of Luther Watson. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on July 22, 2008.

JM: When were you born?

NB: 1927.

JM: When you were growing up, where were you living?

NB: We lived in Erlanger, Kentucky, but we moved to Covington (KY) in about 1935.

JM: What was your father’s job at that time?

NB: He was a railroader. He worked for all lines out of Cincinnati. He was a switch tender. He would pull the switches.

JM: So he must have needed only one arm to pull the switches?

NB: Yes.

JM: How many years did he work for the railroad?

NB: Almost all his life, after he got his arm messed up. Because he worked for the railroad, we got passes. Mom and my sister Della and I took free trips. We went to Florida. And we went to the New York World’s Fair in 1939. I was nine years old.

JM: Did he do any other jobs with the railroad besides a switch tender?

NB: He worked the extra boards (extra shifts) during the Depression. My mother baked then and had a baking route. We delivered all the baked goods to her customers. She worked out of the home.

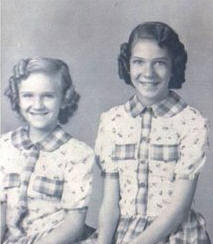

JM: How many children did your parents have?

NB: There were four of us, all girls. I’m the last one left.

JM: Did your father tell you about his arm injury?

NB: Yes. He worked in the bung factory. He walked past one of the machines, and it got switched on somehow and his arm got twisted up in it. It was terrible.

JM: What was the name of the company?

NB: I don’t know.

JM: Did he go back to work at the same company?

NB: Oh, no.

JM: When your father was injured, how was his family able to pay for his medical bills?

NB: I don’t’ know.

JM: What did his father do for a living?

NB: I don’t know. He wasn’t alive when I was born, and his mother wasn’t alive either. His parents were dead when he had the injury.

JM: Who was he living with?

NB: I have no idea.

JM: He sure had a tough life.

NB: Yes, until he met my mom. They had a beautiful life together.

JM: What was your mother’s name?

NB: Mabel Freeman. She had 11 brothers and sisters. Dad had only one brother. His name was Frank. He worked for the railroad, too.

JM: How old was he when he retired?

NB: Probably about 65. He got a pension. He died in 1961. My mom died in 1972. After my father died, she came to California to live with me, because my husband was ill. I had left Kentucky when I was 23, and moved to California.

JM: Did that make it difficult to see your father often?

NB: I saw him only three times after that. He came out to see us.

JM: How did your father cope with having one arm?

NB: Oh, he could do anything he wanted to. He had all his strength in that one arm. He could write, he could eat, and he could drive. He was wonderful, such a good papa. When I got married, he built a whole room underneath the house so we could live in it.

JM: Did he finish school?

NB: He finished the eighth grade, Mom and him both.

JM: How many of his children finished high school?

NB: All of us. Two went to college, Eloise and Della. They completed two years.

JM: Did you work?

NB: Yes. I worked until I was 72. I worked in Cincinnati at a jewelry place. I also worked for McAlpin’s Department Store and managed the yardage department. In California, I was a shoe person the rest of the time. I worked in shoe stores.

JM: What was your mother like?

NB: She was beautiful. She was real sweet and kind, but very stern with us girls.

JM: Did she ever work outside of the home?

NB: Yes, she did, for a little bit. She worked in a candy factory.

JM: What are some of the things your father loved to do?

NB: After we moved to Covington, he started a garden. He had a beautiful garden every year. He had cherry trees and all kinds of vegetables. He had a very good sense of humor. He loved baseball. He went to see the Cincinnati Reds play at Crosley Field. We all did. His favorite saying was ‘LEW: Leave early and walk.’ And that’s what he did. He went to work that way, over the river, across the trestle from Kentucky to Cincinnati, where he worked in the rail yards.

JM: When you worked in Cincinnati, did you also walk across the trestle?

NB: No, I’m afraid I didn’t.

Luther Watson: July 09, 1892 – July 27, 1961.

*Story published in 2009.