Lewis Hine caption: Mamie La Barge at her Machine. Under legal age. Location: Winchendon, Massachusetts, September 1911.

The first time I saw this picture, I thought it might be the best photograph Lewis Hine ever took. More than two years later, I haven’t changed my mind. Mamie is placed perfectly in the center. She looks warmly and confidently into the camera, her eyes focused slightly downward, since Hine obviously positioned himself at her level. With her white dress and her hands held outward, grasping the thread, she looks angelic. The low ceiling and spinning machines frame her claustrophobically. But Mamie does not look confined or in distress; she looks proud, resolute, and incredibly beautiful.

“She was a real huggy grandma. We loved to cuddle up in her lap and snooze. She was very well-endowed, so we used her as pillows. We would bounce on her lap, and she would say, ‘Trot trot to Boston, trot trot to Lynn, you better watch out, or you’ll fall in.’ And then she would open her legs, and we would go flying down on the rug.” -Cheryl Szlyk, granddaughter of Mamie Laberge

Lewis Hine caption: Mamie and her sister Eglantine, about 15 yr. Location: Winchendon, Massachusetts, September 1911, Lewis Hine.

Hine took 40 photographs in Winchendon, and Mamie appears in a dozen of them, six by herself. Mamie’s sister, Eglantine, is in six of them. In her own special way, she is just as eye-catching. In the picture immediately above, the contrast between the girls is striking. Mamie is still radiant and warm, though her eyes are turned to her left, as if she is glancing at her sister. But Eglantine’s head is tossed back, almost defiantly. We will become familiar with that pose as this story progresses.

“She never talked to us much about her life in Winchendon. We know that she didn’t get past the sixth grade, and we know that she had to go to work in the mill to help support her family. I’m sure it wasn’t easy for her. She had to work long hours. -Karen Czelusniak, granddaughter of Eglantine Laberge

The following is from the written recollections of Mary Bosworth, former secretary to Nelson D. White, the last owner of the mill. Ms. Bosworth also served as postmaster of Winchendon Springs. Courtesy of Eric White, great-nephew of Nelson D. White.

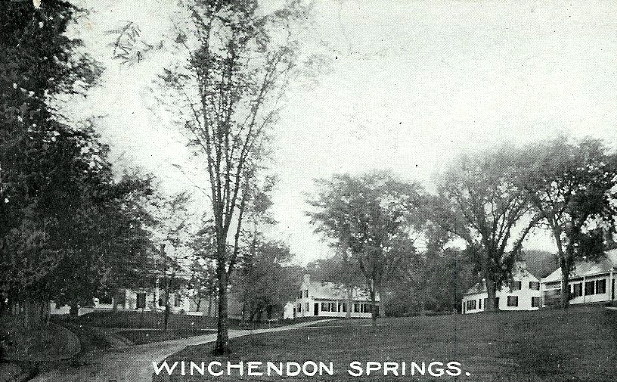

“Deacon White came from West Boylston (Mass.) to Winchendon Springs in 1843. With his six children, he moved to a house on Mill Circle, built in 1799 for a tavern to house the many people who came to the spring to benefit from the water, which was impregnated with iron and sulfur and was a valuable remedy for some ailments.”

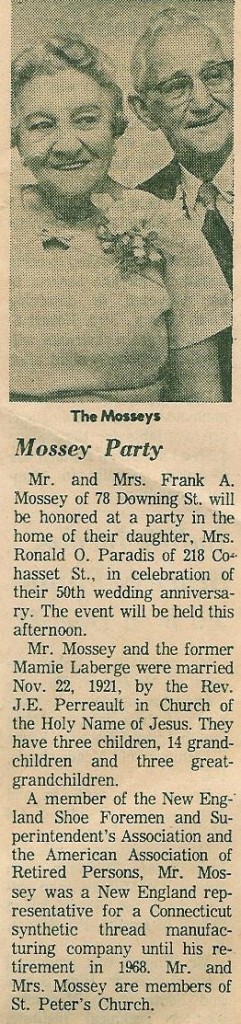

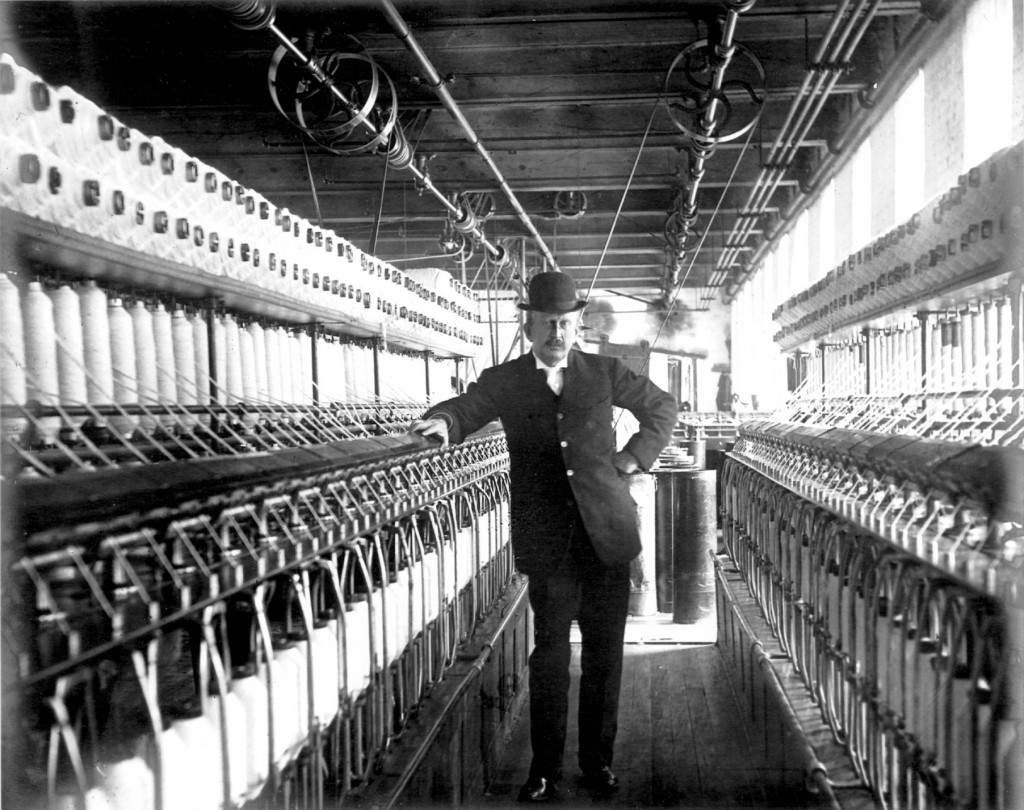

“In 1843, Deacon White and his son Nelson went to an auction of Springs Mfg. Company in Boston, and bought the company for $17,500. They organized Nelson Mills, and in 1857, built the Springs mill and a model village in Mill Circle. All the houses were two-family, painted white with dark doors, gutters and roofs. All had large white chimneys with black bands around the top to keep witches away.”

“If the mill was not running, no rent was charged; if running half time, only half the rent was charged. Rent ranged from $.90 to $2.00 a week. In spring, back yards were plowed by the mill, and they had an open car running on a sidetrack with potatoes for all who wanted to plant. In fall, wood was cut down and trucked to the houses. Buildings were well maintained and paint and wallpaper were available to all who wanted them.”

“Although employees worked long hours, at first 72 hours, there was no great pressure. Pay was small and only received quarterly. Most of the employees came off farms and seemed happy to be with people. In the early days, there was no great distinction between employers and employees, and all joined in the dancing.”

“During World War II, our entire production was taken over by the Navy Department. We ran three shifts, about 500 employees, and had government men here at all times. Those years were very successful financially, so the company decided to spend some of that money by putting indoor plumbing in the 86 tenements they owned. Families were moved from house to house so kitchens could be changed, pantries removed and indoor plumbing put in.”

“However, during those years, new plants were being built, especially in the South. Textiles were dying out in New England and White Brothers decided to sell. All the mill houses were sold, principally to the people in them. The last cloth was run off in 1956. The rest of the village and mills were sold to Ray Plastic Co. in 1959.”

**************************

“Joseph Nelson White was born at Winchendon Springs, Massachusetts, October 4, 1851, son of Nelson Davis and Julia Davis Long White. The first of the family in America was Thomas White, who came over on the ship “Annabel” from England in 1660 and settled in Charlestown, Massachusetts. He was a Freeman of Charlestown in 1666, and admitted to the Church in 1668.”

“He attended the schools of his native town until his fifteenth year, when he was sent to the Highland Military Academy in Worcester, where he remained for two years, graduating in 1867 with high rank. He then spent a year at the Institute of Technology in Boston, taking a course in mechanical engineering, English literature, physics, and chemistry.”

“In 1869 he entered his father’s mill at Winchendon Springs, and began that connection with the business which lasted for fifty years. In 1876, in addition to the work of the mills, he engaged in a cotton brokerage business, which he followed for several years, and which proved to be very lucrative. In 1877 he bought, with his brother, Zadoc, the Jaffrey Mills, starting out simply with credit and developing very shortly a profitable and constantly growing enterprise. He was one of the prime factors in the various additions to the Springs estate, particularly in the enlargement of the Springs mill by the building of a large weaving mill.” –Historical Register: A Record of People, Places and Events in American History, 1921

**************************

“Winchendon (White Bros.): An application was received, Jan. 19, 1900, from White Bros, of Winchendon Springs, for advice relative to the quality of the water of a spring at Winchendon Springs. The Board replied to this application as follows:

June 8,1900: In response to your request for advice as to the quality of the water of a spring at Winchendon Springs, the State Board of Health has caused the spring and its surroundings to be examined and a sample of the water to be analyzed. The results of the analysis show that the water is clear, colorless and odorless, but it has evidently been somewhat polluted by sewage, probably from houses on the higher lands sloping toward the spring, and the water has been subsequently partially purified in its passage through the ground. One characteristic of the water is the excessive quantity of iron in solution, which, when the water is exposed to the air, gradually oxidizes and separates out of the water, forming a rusty precipitate. While in its present state this water may not be unsafe for drinking, it is not a desirable drinking water, and, considering the circumstances, the Board would advise that its use be avoided.” -Annual report of the State Board of Health of Massachusetts, Volume 32

The mill is still in operation. The facility is currently occupied by the Mylec Corporation. Founded in 1970, it is a leading manufacturer of street hockey equipment. The Winchendon Springs Post Office is also located at the mill, and has been in continuous operation there since the 1890s.

Lewis Hine caption: Mamie La Barge and a part of her family of which there are 13 in all, nine in the mill. Location: Winchendon, Massachusetts, September 1911.

According to other Hine photos of the family, and the assistance of several descendants, those pictured are: Henry (with dog), Francis (wearing hat with band), Odella (next to Francis), Mamie (next to Odella), Josephine (standing at left), Eglantine (next to Josephine), mother LaRose (seated next to Eglantine), and Louise (right).

“Up until a few years ago when they totally redid the house and took off the porch, the upstairs had a door facing Glenallan Street and it was numbered 201 Glenallan, and the downstairs had a door facing Mill Circle, and it was numbered 21 Mill Circle. I know that because my mother’s sister lived upstairs and my mother’s uncle lived downstairs. -Esther Grimes, granddaughter of Henry Laberge

**************************

Montmagny, a small town in Quebec, sits on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River, about 30 miles east of Quebec City. It was founded in 1678, and named in honor of Sieur de Montmagny, second governor of New France. The economy is currently supported by small industries such as foundries and carding mills, and the surrounding area is populated by vegetable and dairy farms. It is 400 miles north of Winchendon.

On January 5, 1854, Onesime John Laberge (often misspelled Labarge in later years) was born in Montmagny to Jean Baptiste Laberge and Euphemie Coulombe Laberge. When he was about 17 years old, he left his parents and headed across the border to America to work for the White family in Winchendon Springs. Some sources suggest that he was recruited by the owners, along with many other French Canadians.

*All photos provided by various members of the Laberge family, except those noted.

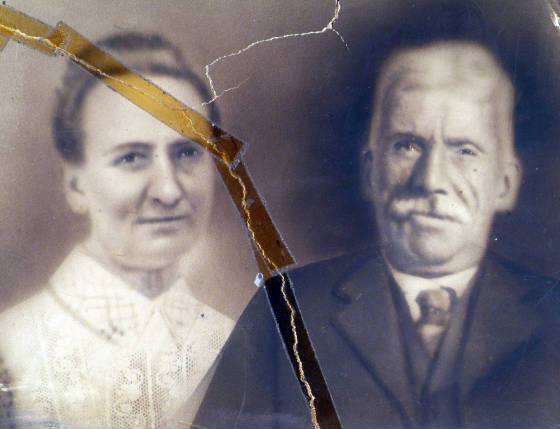

On April 19, 1880, Onesime married LaRose Marie Branconnier, in Winchendon. She was born in Saint-Valérien-de-Milton, Quebec on February 14, 1863, the daughter of Antoine Branconnier and Marie Louise LaFrenier Branconnier. When she was only two years old, her mother died, and a year later her father married Marie LaPointe. The family moved to White River Junction, Vermont, about 1876, and then to Winchendon.

When 26-year-old Onesime and 17-year-old LaRose took their vows before 40-year-old priest Fr. John Conway, they were both working at the cotton mill in Winchendon Springs. They could not have dreamed then that they, and their many children to follow, would become one of Winchendon’s most prominent and important working-class families; nor could they have dreamed that they would be immortalized 31 years later by photographer Lewis Hine, who at the time of their wedding, was the six-year-old son of a restaurant owner in Oshkosh, Wisconsin.

Lewis Hine caption: Mamie and her sisters and brothers who work in the mill. Location: Winchendon, Massachusetts, September 1911.

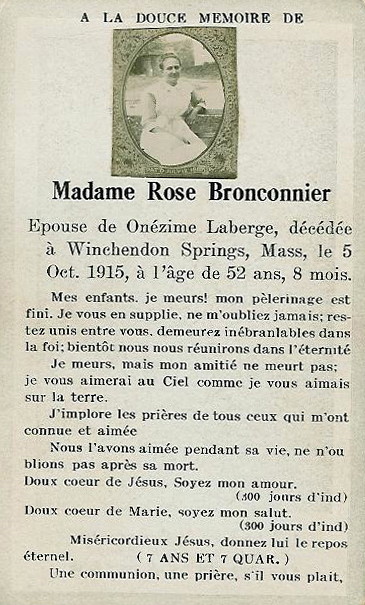

When Hine arrived in Winchendon in 1911, Mr. and Mrs. Laberge had 11 children. They had lost Maude, who died in 1892 at six months, and their last two had died at birth in 1903 and 1904. They were living at 11 Mill Circle, a large house several hundred feet from the mill. It is no longer there. On October 5, 1915, four years and a month after the photographs were taken, Mrs. Laberge passed away suddenly at the age of 52, with four of her children still in their teens: Mamie, Eglantine, Odella and Frank (Francis).

“Mrs. Rose (Broconnier) Laberge, wife of Onesime Laberge of Mill Circle, died at Millers River hospital last week Tuesday. Her age was 52 years, 4 months, and 6 days. Mrs. Laberge was born in Rochton, Canada, Feb. 14, 1863, only daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Antoine Broconnier (Marie Louise LaFrenier). When she was only two years old her mother died, and a year later her father married a Miss Marie LaPointe, and to them six children were born, four girls and two boys. When a young girl her parents moved from Canada to White River Junction, Vt., where they made their home for several years until they came to Winchendon to live. On April 19, 1880, she married to Onesime Laberge, in the Church of I. H. of Mary by the Rev. John Conway. Fifteen children were born to them; eleven of whom are living — Henry, Joseph, Alfred, and Frank of Mill Circle, Josephine of Taftville, Ct., Mrs. Marie Louise Laprise of Mechanic square, Rose Anna, Eglantine, Mamie and Odella. Besides her children she is survived by four half-sisters and two half-brothers, Mrs. Vital LaBlanc of Fitchburg, Mrs. Oscar Broconnier of Spencer, Mrs. Dolphus Broconnier of Marlboro, Mrs. Wilfred St. Pierre of this town, Antoine and Joseph Broconnier of Spencer. Mrs. Laberge has always been a hard worker to help out her family needs. She was kind and generous and always ready to help others. She was well liked and will be greatly missed by all who knew her. Funeral services were held from her home on Mill Circle last Thursday, with a requiem high mass at St. Mary’s church. Burial was in Calvary cemetery, the bearers being Wilfred St. Pierre, Frank LaPrise, Henry and Joseph Labarge, and Antoine and Joseph Broconnier of Spencer. The flowers were many and were given as follows: Wreath of roses, N. D. White; spray of roses, Miss Theresa Fanning; spray of roses, Miss Emma Smith; spray of roses marked “N. D. C.” National Drum corps; spray of roses, Young Ladies’ Sewing club; spray of lilies, White school, Grades 5 and 6; asters, Mrs. Chas. Steele; asters, Mrs. Addie Horton; lilies and roses, Mrs. Frank LaFrenier of Rindge, N. H., lilies and roses, Geo. H. Flint.” -Winchendon Courier

*Daughter Agnes is missing from the list of survivors.

Translation below by Ellen Manning Lind

In loving memory of Madame Rose Bronconnier, wife of Onesime Laberge, deceased in Winchendon Springs, Mass., October 5, 1915, at the age of 52 years, 8 months. My children, I die! My pilgrimage is over. I implore you, do not forget me ever, you stay united, remain steadfast in faith, soon we will meet in eternity. I die, but my friendship does not die; I love you in Heaven as I loved you on earth. I implore the prayers of all who have known and loved. We loved during his life, do not forget after his death. Sweet Heart of Jesus, be my love (500 days of ?). Sweet Heart of Mary, be my salvation (300 days of ?). Merciful Jesus, give him eternal rest (7 years and 7 quarters ?) A communion, a prayer, please.

**************************

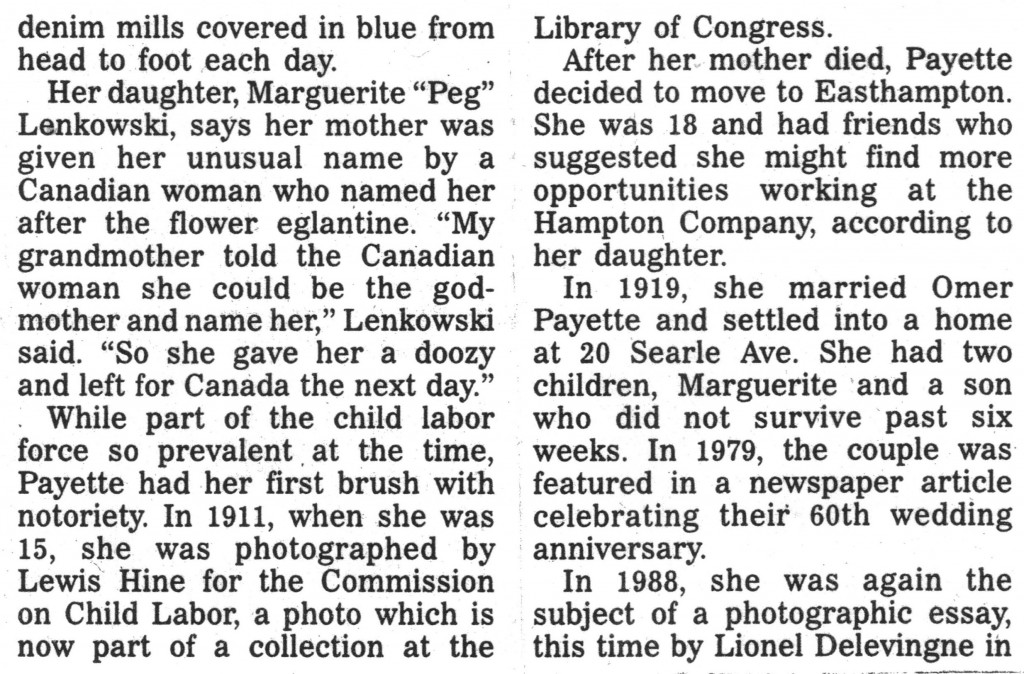

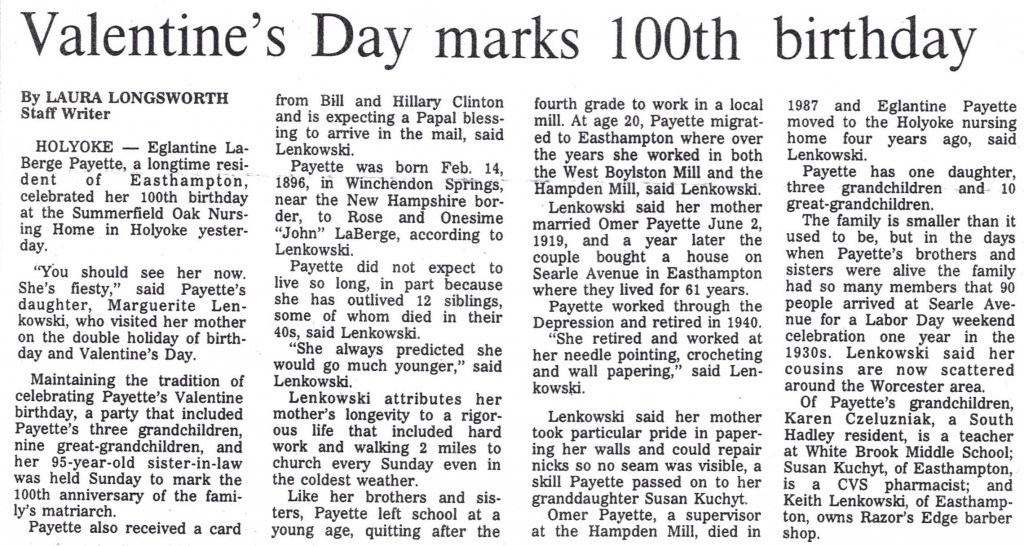

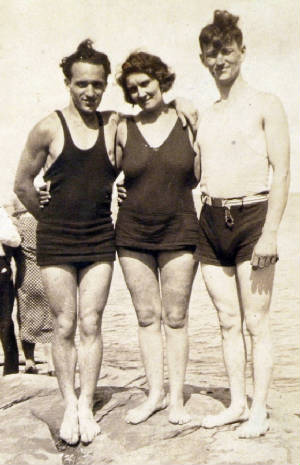

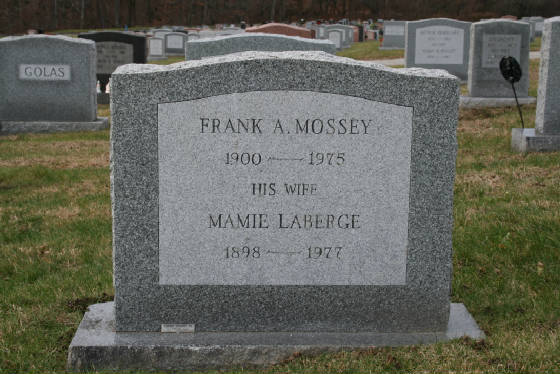

By 1920, six of the children had left Winchendon. Josephine and Agnes moved to moved to Taftville, Connecticut. Joseph moved to Easthampton, Massachusetts. Eglantine also moved to Easthampton, and married Omer Payette in 1919. Mamie and Odella moved to Worcester, boarded together and worked at a shoe factory. In 1921, Mamie married Frank Mossey; a year later, Odella married Maurice Doyle.

Onesime stayed in Winchendon until 1941, when he went to Worcester to live with his son Frank. He died three years later at the age of 90. The wake was at the home of son Henry, at 4 Mill Circle. Henry passed away in 1970, at the age of 89. Some sources indicate that he was the longest serving employee of the mill, having retired when it closed in 1956. Thus, it is likely that at least one member of the Laberge family was working at the mill every year from 1871 until it shut down — a total of 85 years.

With considerable help from the archives of the Winchendon Courier, the Fitchburg Sentinel, and the Daily Hampshire Gazette, as well as the town clerk’s office in Winchendon, I was able to contact and interview Eglantine’s three grandchildren, who had known about one of the photographs of Eglantine for a few years. I also interviewed two of Mamie’s granddaughters, along with their father, and one of Odella’s sons. In addition, I received considerable assistance from Esther Grimes, one of Henry’s granddaughters, who has been researching the family history for many years. She still lives in Winchendon.

“My aunt bought the house when the White Brothers sold it. My cousin moved the front doors to the middle of the house, so it really doesn’t look the same.” -Esther Grimes

“When Aunt Mamie came to town (Winchendon), usually my Aunt Eglantine would come, and they would bring Aunt Della. You’d get a call from Spring Village, and they’d say, ‘Your Worcester relatives and your Easthampton relatives are here.'” -Esther Grimes, granddaughter of Henry Laberge, who was Mamie and Eglantine’s oldest sibling

Edited interview with Joseph Doyle, son of Odella Laberge Doyle, and nephew of Mamie and Eglantine Laberge. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on November 11, 2010.

JM: When were you born?

Doyle: 1941, in Worcester.

JM: What was your father’s name, and when did your mother marry him?

Doyle: She married Maurice Doyle in 1922. He was 10 years older than her. She had three sons with my dad, and two stepsons from my dad’s previous marriage. She also had two daughters who died at birth. I was the last child. She was 42 when I was born.

JM: What did your dad do for a living?

Doyle: He was a steamfitter for Pullman Standard, which was in Worcester. He did all the steamfitting for boxcars and engines.

JM: When did your dad die?

Doyle: In 1956, when I was 15 years old.

JM: Your mother died in 1987, so she was a widow for 31 years.

Doyle: That’s right.

JM: Did your mother work when you were growing up?

Doyle: She worked just about her entire life, in any kind of job she could get, whether it was in a mill, like a paper factory in Worcester, or in her later days, when she worked at Newberry’s and Woolworth’s as a clerk. She was also a craftsman. She did wallpapering and painting for people’s apartments in the neighborhood. In the ‘40s and ‘50s, when I was growing up, my dad was working full time, and my mother was working as many part-time jobs as she could, so my brothers and I were basically home alone during the day. And those were the days when we weren’t served lunch at school. We came home every day for an hour for lunch and walked into an empty house. We didn’t have Mom making sandwiches for us. At the dinner table, my parents didn’t have time to sit down for a long time and have conversations.

JM: Did she work because she wanted to, or because she needed the money?

Doyle: She had to work, although I think she would have worked no matter what.

JM: Did she tell you about her life as a child, and the fact that she worked at the mill in Winchendon?

Doyle: No, she didn’t. We didn’t discuss that at all.

JM: When did you learn about the child labor pictures of your family?

Doyle: A newspaper reporter was doing an article about Aunt Eglantine. She was the oldest person in Easthampton. That’s when I found out that Eglantine’s photo was in the Smithsonian, but at that time, we didn’t know there were more pictures of the family. I didn’t follow up on it until you told me about it. So I went on the Library of Congress website and saw all the pictures and sent them to my brothers. We had a lot of discussion about it.

JM: What do you think about the fact that your mother was working in the mill when she was perhaps as young as 10 or 11?

Doyle: I think it was something they had to do. It was expected, just like our kids are expected to finish high school and go on to college. They were expected to go to work and bring in some money for the family. I can remember as a real young child that my two older brothers, one in high school, and one already out of high school, had to pay board if they lived in the house for any period of time. My mother’s work ethic was incredible. She probably got that from the fact that she worked at the mill as a child. What amazes me is that without an education, she was able to educate herself. She could read and write in French, but she had to learn English, too. I remember her writing notes for me in school, and they were just one or two sentences. She was not one to write a lot. It was probably tough at that time to function in a society where she had to account for all her money, write letters, and whatever else she had to do.

I think I have a strong work ethic. I think I got that from my mother, who got that from her parents and her family. I have a greater appreciation of that now, and appreciate much more what my mother and father did to raise five boys. When I was a kid, I probably wondered why I didn’t have more, and why we were living in a three-decker while my friends were living in nicer houses up on the hill.

JM: Did you go to college?

Doyle: Yes, to the University of Massachusetts, in Amherst. I went there on a football scholarship. I was a physical education major as an undergrad, and then I got a master’s degree in school administration. After that, I was a football coach for 17 years at Hoosac Valley High School in Adams (Mass.), and then I became a school administrator at the same school, and later at Adams Middle School.

JM: What were Mamie and Eglantine like?

Doyle: Oh, Mamie was wonderful, but she seemed to have the edge on her all the time. Her language was a bit on the rough side, and she swore a little more than the others. She had that attitude that life was tough for her. She was a heavy smoker, and she liked her little nips once in a while. Her sister, my Aunt Agnes, who lived in Taftville, Connecticut, was the opposite. She was the typical grandmother type. She baked a lot. She always had homemade cookies and pies.

JM: What was Eglantine like?

Doyle: She was a talker. She was the only aunt that I would go and spend two or three days with. I loved going to her house because she had more of the good food that I never got at my house. She always had cookies in the cookie jar, and they weren’t Oreos. I used to sleep on a big couch on her porch in the summertime.

JM: Your grandfather, Onesime, died in 1944, so you would have known him for only three years. Do you remember him?

Doyle: He lived his last years in Worcester with Uncle Frank and his wife, my Aunt Margaret. I remember going there on the bus. They lived on the first floor in a three-decker, and Pepere would be out on the front porch in his rocking chair smoking his pipe. I remember getting up on his lap.

JM: Do you remember your mother ever talking about her mother dying? She would have been just 16 when that happened.

Doyle: I don’t remember my mother ever talking about my grandmother or my grandfather. I never saw a picture of my grandmother until last year when I found it on the Library of Congress website after you told me about it. That was the picture with her sitting with her family on the porch in Winchendon. She was a very striking woman. She looks like she would have been in control.

JM: She was 48 years old then, and she died four years later.

Doyle: She looked a lot older than 48.

JM: Did you go to Winchendon when you were growing up?

Doyle: As a child, I remember going to Winchendon just about every other Sunday. I can remember vividly heading up to Winchendon on a Sunday for dinner with my cousins and aunts and uncles. It was the thing to do. I can’t tell you the address of the house, but it was up on a hill, an old colonial-type home, white, with a barn in the back, which was used for cold storage.

We’d get there about 11:00. My older aunts were like the matriarchs of the family, and they went out in the kitchen and prepared the food for the day. Then we’d get something to eat, and when we were finished, I would go outside and play. My aunts and uncles would sit around and talk and smoke. The men were in one room and the women were in another room. There was a lot of French talk going on with the women – the Canadian Canuck French – and a lot of smoking going on with the men.

By mid-afternoon, the men would get tired of sitting around, so they would go outside and walk up the hill to look at the garden, or the rabbits and chickens. Uncle Pitou (Henry Laberge) would take me up there and tell me not to touch the rabbits and chickens, but he would find an egg, and I thought that was great to find an egg under a chicken. You couldn’t do that in Worcester.

Then the men would throw big boulders similar to the way you throw the shot put. They would pick them up and see who could throw them the farthest. My dad was a pretty strong guy. He was an ex-boxer and baseball player and a pretty tough Irishman. But he would get beat by Uncle Pitou, who was all skin and bones, because he had the leverage and the technique to throw the boulders. My dad would get up there and just try to muscle it out. My cousins and I would sit and watch these grown men throwing big rocks. I don’t remember if they had been drinking, but they had a great time.

I remember the smells. I can still smell my Uncle Pitou. He had this strong tobacco smell. They all chewed. At that time, I didn’t know what that was. They also smoked pipes. There were other smells in the house, like the French meat pies and the cabbages. That smell was in the house all the time. One of the foods we had up there was blood sausage. It was gross. They would fry it up and have it with beans.

We would leave late in the afternoon or early in the evening to drive back to Worcester, which seemed like an eternity in those days, but probably was only about an hour. Everybody left about the same time, and we’d be back up there in another week or two.

JM: Do you remember the mill being there? It was right next door.

Doyle: No, I don’t remember it, probably because it wouldn’t have been important to me then. And I don’t remember anyone saying, ‘Hey, Joe, that’s the mill where we used to work.’ We went up there every couple of weeks until I was in the fourth or fifth grade, and then it just seemed to stop. Instead, we started meeting every New Year’s at Uncle Frank and Aunt Margaret’s house. It was an all-day affair. They had a six-room apartment, and it got pretty crowded. All the kids were in one room, all the men in another room, and the women were in the kitchen. In the late afternoon, my dad and mom would play the fiddle, and everyone would sing songs in French. But we kids didn’t just sit on the floor and listen to it; we were outside doing other things.

I remember that Uncle Frank was a real party guy. Whenever there was a wedding or an anniversary, he was there, and he was the life of the party. He danced his fool head off. I can remember him sweating a lot, but he’d still jump up and dance with anybody who wanted to dance. But when he wasn’t at a party, he seemed to be a little bit of a grouch. And I remember hearing stories about Uncle Joe (Frank’s older brother) when we went to Easthampton to visit Aunt Eglantine. When he was old, he was still riding his bike around town. You could see him riding down the street with a pipe sticking out of his mouth.

JM: When was the last time you were in Winchendon?

Doyle: It has to be 35 or 40 years ago. My brothers and I had contact with the family in Winchendon only at funerals and wakes after we grew up and started our own families. I certainly have enjoyed the pictures and learning more about the history of my family, but I don’t know how much my children have gotten out of it. I sent the pictures to all seven of my children, but they’ve probably put them away somewhere. But when they get to be in their sixties or seventies, they’ll probably take them out, and it will mean something to them. Right now, they are too busy raising their families. When I was raising my family, I really didn’t give a hoot about what happened in Winchendon, and what happened to my aunts and uncles. But as you get older, you start looking back.

Lewis Hine caption: Eglantine La Barge, an adolescent spinner, working in Spring Village Mill for 2 Years. Location, Winchendon, Massachusetts, September 1911.

Edited interview with Karen Czelusniak (55), Susan Emerson (53), and Keith Lenkowski (50), grandchildren of Eglantine LaBerge. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on June 13, 2009.

JM: Did your grandmother ever tell you about working in the mill when she was young?

Karen: She never talked to us much about her life in Winchendon. We know that she didn’t get past the sixth grade, and we know that she had to go to work in the mill to help support her family. I’m sure it wasn’t easy for her. She had to work long hours.

Keith: It probably wasn’t a very happy time in her life, so she probably wanted to forget it.

Susan: It was a tough life. They had no childhood. They had to leave school to help support the family. I compare it to what we had when we were growing up, and when our children were that age. We didn’t have to go through any of that.

JM: You have known about these photos for quite a while. When you first saw them, did you ask your grandmother about them?

Keith: By the time we found out about the photos, she had aged quite a bit, and she didn’t have any recollections of that time.

Karen: She didn’t remember the pictures being taken, and she didn’t recognize herself in them.

JM: My research shows that she moved to Easthampton about 1918, and that she married your grandfather, Omer, in 1919.

Karen: When she first came to Easthampton, she lived in a boarding house. There were a lot of boarding houses there for the girls who worked in the mills.

Keith: My grandfather worked at several mills on Pleasant Street. The last place he worked was at American Made Footwear.

JM: Did your grandmother continue to work after she got married?

Karen: I don’t remember her working at all. When I was born, we lived right down the street from her. When I was a baby, my mother worked for a short time, and Memere took care of me.

Susan: Mom told me that Memere worked occasionally when the factory needed someone for a short time.

JM: When was your mother, Marguerite, born?

Karen: In 1925. There was another child who died young. He was Roland. He died six weeks after he was born, about a year after my mother was born. Memere talked about it all the time. Those were the only children that she had. For a few years after the baby died, they didn’t celebrate Christmas. Finally, my grandfather put his foot down.

Susan: Mom was looking out the window and saw a Christmas tree, and she was all excited and jumping up and down. My grandfather said to my grandmother, ‘Remember, you have another child.’ When we were little, we always went to her house for Christmas dinner.

Karen: I remember her house was always beautifully decorated for Christmas. And on Thanksgiving night, we always took a trip through town to look at the Christmas lights, which were turned on that night.

Susan: Because Memere lost her only son, Keith was the apple of her eye. There wasn’t a single time that Keith ever said. ‘I like,’ or ‘I want,’ and it wasn’t there.

JM: Did you like it that way, Keith?

Keith: I sure did.

Susan: Her family was a big part of her life. We would go to her house all the time. She had a big flower garden on the side of the house. I remember her poppies being a big thing for her. There were a lot of 18-wheeler trucks that would drive on the other side of her fence, where the mill was. The truck drivers would stop and take pictures because the flower garden was so beautiful.

JM: Where was the house?

Keith: It was at 20-22 Searle Avenue, the last house on the street.

Susan: Her grandchildren were very important to her. She made us freeze pops out of fruit juice. In the summertime, we’d get in the car once a week and go to our local Tastee Freez. That was always a big treat for her.

Karen: We never had a babysitter other than Memere and Pepere. And if we stayed over there on Saturday night, we darn well better get up on Sunday morning, because we had to go to church with them. They would walk to church, and we three little ducklings were right behind them. She was firm with us.

Susan: Hence, that determined look on her face in the child labor photos.

JM: She sure looked stoic in those pictures.

Karen: But she had a heart of gold.

Susan: We’d come home from church, and she would get the frying pan going, and we would have a full breakfast. She used to make what she called silver dollars, little tiny crepes. She would serve us big glasses of Tang. That was a big thing then.

Karen: We hardly ever went anywhere for vacation. But if we went with them, we went to visit Aunt Mamie and Aunt Della in Worcester. And we would always spend a week with Memere in the summer. But she was already getting on in years, so it was difficult for her to manage all three of us. We still had to go see Mom and Dad every day, which was just a mile away.

Keith: She had a couch that converted to a bed, and we would sleep in the living room.

Susan: She had a great front porch. It was all screened in. When it was hot in the summer, we would sleep out there.

Keith: We didn’t get much sleep, because the factory on the other side of the fence ran 24 hours a day.

JM: Did you ever go to Winchendon?

Karen: Many times.

Keith: We’d drive up there for afternoon visits.

Karen: It was a long way then, because the roads weren’t very good. We would go to Uncle Pitou’s house. His real name was Henry. He was Memere’s brother. I remember the house being on a hill.

Keith: It was a duplex.

JM: Did your grandmother ever point out the mill to you, which was just below the house?

Keith: When we went to Winchendon, she never mentioned the factories.

Susan: One story sticks out in my mind. There was a pond somewhere near the house. Memere said she was sitting on a dock fishing once, and she had her feet dangling in the pond. A snake swam right between her feet, and that was the last time she did that.

JM: What were some of the differences between Eglantine and Mamie?

Susan: They were a lot alike.

JM: How?

Susan: They were both pretty regimented.

Keith: Almost like they were brought up in the military.

JM: Did they have a sense of humor? Did they ever loosen up?

Keith: That was very rare.

Karen: The only ones I remember having a sense of humor were Aunt Della and Aunt Agnes.

Keith: Memere just wouldn’t cut loose, but Pepere was a lot of fun. He liked to play with us, but Memere was the disciplinarian.

Karen: Pepere played badminton with us until he was quite old. He was easygoing as could be. Nothing ever rattled him. He thought the world of Memere. She could not have had a better husband. I remember going shopping with them. She would never buy a new dress unless she absolutely needed one. If she needed a new dress, she would narrow it down to a couple, and then she would ask Pepere, ‘What do you think? I don’t know which one I want.’ And every single time, Pepere would say, ‘Oh, just get them both.’ And she would say, ‘I don’t need both of them.’

JM: When the family got together, did your Aunt Mamie talk a lot, or was she quiet?

Karen: She wasn’t quiet and off in a corner. She was very similar to Memere. She talked a lot about her family. They were very important to her. Her husband, Uncle Frank, talked to my dad a lot, since they were both in industry. And the women would be in the kitchen talking about family.

Susan: Aunt Mamie was bigger and heavier than Memere. And I don’t remember her being as warm and loving.

Keith: She was kind of cool.

JM: Did they speak French at all?

Karen: All the time, to each other, but not to us.

Keith: When they wanted to talk about something that they didn’t want us to know about, they talked French.

Susan: And we wouldn’t ask them about it. In those days, that would have been disrespectful. We just sat there and kept quiet.

JM: Could they read and write well in English?

Susan: They did okay. I have recipes that Mamie wrote out. Memere would read the paper, but she wouldn’t sit down and read a book. They didn’t grow up with that.

Keith: Memere used to do jigsaw puzzles.

Susan: She was an excellent seamstress. She had an old push pedal sewing machine in the kitchen. Pepere converted it to electric.

Karen: She was an excellent cook. She made lots of French food, like meat pies and ragout.

Susan: She was a very nervous person.

Keith: If the phone rang, she would just about jump out of her seat.

Karen: My grandfather always drove. Memere was way too nervous to drive. Pepere tried to teach her once, but by the time it was over, she said, ‘I’m all done.’ That was the last time she ever drove.

Susan: She had her routines. If you went over there on Saturday night, you had to watch Lawrence Welk. She wallpapered. She never paid anyone to wallpaper her rooms.

Karen: She loved iced tea.

Susan: She never drank coffee.

Karen: She loved to play canasta.

Susan: I remember her starching Pepere’s shirts. He always wore white dress shirts. She ironed pillow cases and underwear. She did laundry every day, and ironed every day.

Karen: I remember that when she was quite old, she used to drink these little tiny cans of beer, about four ounces. My husband would say to her, ‘Hey Memere, let’s have a beer.’ And she’d say, ‘Don’t mind if I do.’ She would put salt in it. It’s funny, but when we were growing up, we never saw either one of our grandparents drink. It was not in the house.

JM: Was she called Eglantine?

Karen: She was called Tine (pronounced Sin). Eglantine is the name of a flower.

JM: I read that when she turned 105, the governor awarded her a special chair. What did she think of that?

Karen: Unfortunately, she wasn’t coherent by that time. She didn’t even know when it was her 100th birthday. She didn’t recognize any of us.

JM: How old was she when she lost her memory?

Karen: In her nineties.

Keith: She was good till she was about 94. Then she went downhill quickly.

Karen: When she was about 95, she decided in the middle of the winter that she was going to walk over to visit my mother, who lived in housing for the elderly, not very far away. But she fell down on the ice and hit her head. That might have been the beginning of the end. After that, it was difficult for her to live by herself. My grandfather had already passed away. So she had to go into a nursing home.

JM: Did any of you go to college?

Karen: Sue and I did, and Keith didn’t. I became a teacher. For the last 15 years before I retired, I taught seventh and eighth grade language arts and social studies. We used to do a lot of studying about the girls in the Lowell mills, but I never had any idea that Memere would have also been a mill girl. We learned about all the conditions in those mills that caused all kinds of illnesses. Memere must have been exposed to those conditions.

JM: And yet, she lived to be 105.

*Correction to article: Eglantine was not the second child, she was the eighth child.

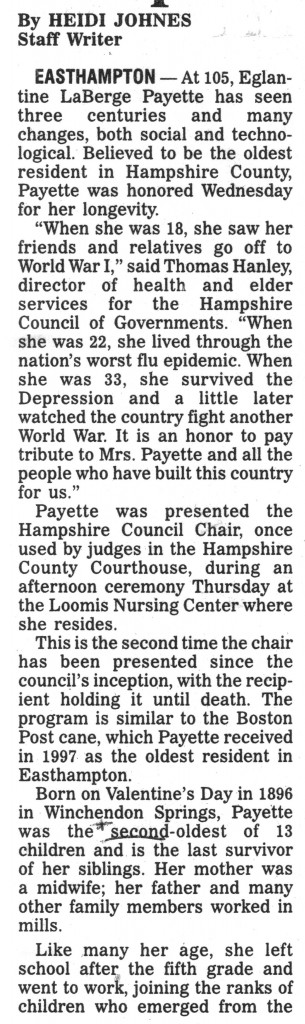

Article published January 27, 2001. Reprinted with permission of the Daily Hampshire Gazette. All rights reserved.

Lewis Hine caption: Group of workers going to work at 6:45 A.M. In Spring Village Mill. In this group are Mamie La Barge, Elizabeth and Lumina Demarais, Als de Gauthier, Erena La Prise, Winchendon, Massachusetts, September 1911.

Karen: I can’t imagine what she would have gone through when she was little.

JM: She might not have been unhappy in Winchendon. It’s likely that when the girls and boys got to be eight or nine, they would be hanging around the mill with their older brothers and sisters. They probably felt good when somebody gave them a job to do. They might have picked up a little extra money for the family, which they would have been proud of. They lived in a very tight community. They would have played a lot when they weren’t working. There were a lot of shortcuts through the woods to get to various things. They walked a mile and a half to church. They probably would have enjoyed that walk. They walked to everything. The town was bustling then. It might have been a pretty decent life for them. I doubt if they were real poor, considering the fact that so many of the children were working. They rented from the mill owner, and the rent would have been fairly low. It was probably a relatively secure and predictable life for a while. But I am sure most of them would have wanted to go elsewhere when they got older.

Susan: I remember my grandparents telling a story about having to live through the Depression, and that they were one of the few families that were able to hang on to their home. They were very proud of that. I’m a pharmacist. I remember Memere sitting at the kitchen table at Mom’s house the day that I got the letter from the Board of Pharmacy, telling me that I had passed, and that I was officially a registered pharmacist. Memere was the first one to know. She was very proud of me.

Karen: When she finally had to go to a nursing home, it was very difficult for us. I actually was there right before she died. I remember saying to her, ‘Go see Pepere.’ That was tough. But, you know, she had a good long life. She was around to see all 10 of her great-grandchildren born.

Above photograph and text from Franco – American Viewpoints, interviews by Eloise Briere, text by Nicole Vaget, and photography by Lionel Delevingne. Courtesy of the Wistariahurst Museum, Holyoke, Massachusetts.

Above photograph and text from Franco – American Viewpoints, interviews by Eloise Briere, text by Nicole Vaget, and photography by Lionel Delevingne. Courtesy of the Wistariahurst Museum, Holyoke, Massachusetts.

Eglantine Laberge Payette was born and raised in a house no more than 200 feet from the textile mill in Winchendon where she worked as a child. She lived within a half-mile of the two mills where she worked in Easthampton as a young adult. The house she lived in almost 75 years was right next to another mill. She is buried just across the river from those three mills.

Lewis Hine caption: A modest young French girl of 13 years. Spinner in the Spring Village Mill, runs six sides. Mr. Hine saw her working Sept. 2. Said, “I’d rather work.” Been working since last February. Location: Winchendon, Massachusetts, September 1911.

Edited interview with Ronald Paradis, son-in-law of Mamie LaBerge (widower of Mamie’s daughter Shirley); and Ronald’s daughters (Mamie’s grandchildren), Debra Begonis and Cheryl Szlyk. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on June 2, 2010.

JM: Ronald, when did you marry Shirley, Mamie’s daughter?

Ronald: 1955.

JM: How long had you known her before you got married?

Ronald: Since the third grade.

JM: Did you go to school with her all the way through until you graduated?

Ronald: When she was a teenager, she traveled around the country with her parents, Mamie and Frank. When I got out of the service at age 20, she moved from Pennsylvania back to Worcester, and we got married.

JM: When you married Shirley, was she working?

Ronald: Yes. In Pennsylvania, she was working for a furniture store. When she moved back to Worcester, she worked at a few places, including the W.T. Grant department store.

JM: Did she continue to work while you were married?

Ronald: Off and on. She worked for the Hallmark store, and she worked for Mechanics Bank for about seven years, as a drive-up teller.

JM: When did she pass away?

Ronald: March of 1993.

JM: You said that she traveled around the country with her parents when she was a teenager. Why were her parents traveling so much?

Ronald: Frank Mossey, Mamie’s husband, was in the shoe business. His company manufactured infant shoes. He would go to one factory after another and repair machines. And Mamie traveled with him.

JM: How many years were they on the road?

Ronald: I remember them leaving to go to California in 1948. So they traveled about six years altogether.

JM: Did they always travel by car?

Ronald: Yes. They would get an apartment at each city they stayed in. They would often stay for months at a time. Sometimes, Mamie worked while they were there, possibly in the shoe factories.

JM: Did you live near Mamie when you were growing up?

Ronald: She lived in Worcester on the same street that I lived on, Chandler Street. It was in a big apartment block, with apartments on both sides, maybe six stories, an enormous building. They lived there until they started traveling. When they came back in 1955, they lived in Webster (Mass.) on School Street. Later they moved back to Worcester, on Downing Street. At the time Shirley was born, in 1937, they were living on Stafford Street in a three-bedroom apartment.

JM: Did they ever own a home?

Ronald: No.

JM: How many children did they have?

Ronald: Three: Raymond, George and Shirley.

JM: What was Mamie like?

Ronald: She was a very funny person, and liked to joke once in a while. She had special names for me.

JM: What did she call you?

Ronald: I can’t remember all of them, but the ones I do remember I can’t repeat. She was a very friendly person, and she was always doing something for somebody else. She cooked for many organizations and social clubs.

JM: Did she speak French?

Ronald: She could speak it, but I very seldom heard her doing it. She would speak it to her sisters.

JM: Did she ever talk about growing up in Winchendon?

Ronald: No, she didn’t talk about the past. She was always looking ahead.

Cheryl: When we were little, Debra and I would sleep over at Gramma’s house. She always made toast with peanut butter in the morning. She was funny. She used to call me something in French, which I think meant that I was being a pain in the butt. It’s strange, but she often used the word ‘me’ at the end of a sentence.

JM: Give me an example.

Cheryl: ‘I don’t like the weather me.’ When she said that she liked something, or didn’t like something, she would end the sentence with ‘me.’ And she had a heavy French-Canadian accent.

Ronald: Debra and Cheryl had good times with Mamie when they were young. She would take them to the store and buy them coats and shoes and things like that.

Debra: I don’t remember doing much shopping with her. But I remember doing jigsaw puzzles with her.

Cheryl: And we played Parcheesi, too. She was a real huggy grandma. We loved to cuddle up in her lap and snooze. She was very well-endowed, so we used her as pillows. We would bounce on her lap, and she would say, ‘Trot trot to Boston, trot trot to Lynn, you better watch out, or you’ll fall in.’ And then she would open her legs, and we would go flying down on the rug. It was hysterical. Deb, do you remember when she cut our hair, pixie style? We were about six and seven then. I didn’t like it.

Debra: I think we liked it then. When we had lunch, she would put on her game shows and set up those trays in front of the TV. We’d have sardines and crackers.

Cheryl: It was the biggest treat to go over to Gramma’s.

JM: What was your grandfather Frank like?

Debra: He was pretty quiet.

Cheryl: He wasn’t very hands on, like Gramma was. He was more of a thinker than a talker. He smoked a pipe, and we loved the smell of it. He had an old black typewriter, and we liked to hang around with him and type. And he had a camera, and he loved to explain to us how it worked.

Debra: He was very intelligent.

Ronald: He was very interested in politics and what was happening in the world.

JM: Were there a lot of family get-togethers with Mamie’s sisters and brothers?

Cheryl: Oh, yes. I remember once sitting on the couch at Gramma’s house, between Eglantine and Gramma. The living room was full of people. Everyone was speaking with that same accent. I thought it was fascinating to just sit there and listen to them. They would go on and on about something, and when they wanted to say something that they didn’t want us kids to hear, they would speak in French.

JM: Did you ask what they were talking about?

Cheryl: Yes, and they would say, ‘None of your business.’

Lewis Hine caption: Group fo [i.e., of] workers going to work at 6:45 A.M. In Spring Village Mill. In this group are Mamie La Barge, Elizabeth and Lumina Demarais, Als de Gauthier, Erena La Prise, Winchendon, Massachusetts, September 1911.

JM: How were Mamie and Eglantine different from one another?

Cheryl: Eglantine was hysterically funny. She liked to crack a joke. I would always hear her laughing. And then she would get Gramma going, which wasn’t easy to do.

JM: One of Eglantine’s grandchildren told me that when Eglantine walked into a room, you knew it, like she was almost announcing her entrance.

Cheryl: That’s right.

JM: In the pictures of Eglantine and Mamie standing together, Mamie looks friendly and giving to the camera; Eglantine looks stoic and strong willed.

Cheryl: Eglantine was always aware of what was going on. She was a very tough woman, but she was also a lot of fun. She liked to make herself known in the room. She was always the first one to start talking about something. She did a lot of the talking. She was like the leader of the group.

JM: Did any of you ever go to Winchendon?

Ronald: Yes. Mamie often asked my wife to take her there.

Debra: I remember visiting someone called Pitou. There were a lot of people there, including a lot of children.

JM: When was the last time you went to Winchendon?

Ronald: That was an awfully long time ago.

Debra: I was about 10, maybe. So it must have been about 40 years ago.

JM: The mill where they were photographed is still there. It makes street hockey equipment now. The spinning machines are no longer there, but the pipes and ceiling fixtures are still there, and you can actually spot locations in the mill where Mamie and Eglantine might have been standing when they were photographed.

Debra: I can remember all the rides we would take up there. Sometimes we were just passing through on the way to somewhere else. We’d drive by, and someone would say to me, ‘There’s the house your grandmother grew up in.’

JM: When did you find out about the Lewis Hine photographs?

Debra: Not until you sent them to me.

JM: That’s strange. Eglantine’s grandchildren have known about the photos for quite a few years. Hine took 12 photos of Mamie.

Cheryl: I would like to know why her family was singled out.

JM: It might have been their accessibility. Hine had a limited amount of time to take pictures, and they might just have been around at the time. They might have been more willing to be photographed. I am sure that some of the children would have been afraid of the camera, and would have avoided Hine.

He often took several photos of children who were beautiful or otherwise very photogenic. I think he felt that those pictures would attract more attention and sympathy from the people he wanted to persuade to support child labor laws. Mamie’s pictures, especially the one of her in the mill, are quite stunning.

Lewis Hine caption: Mamie La Barge, Winchendon, Massachusetts, September 1911.

Cheryl: She had very vivid features. Her eyebrows were very distinct, and so was the bone structure in her face.

Debra: Her skin was dark. She used to say, ‘I can sit in the shade and get a tan.’ She used to say that it was the Indian in her.

JM: I’ve heard from other descendants that the family might have Native American ancestors.

Ronald: Mamie told me once that she had Indian blood in her.

JM: Was Mamie in reasonably good health in her later years?

Ronald: Yes, she was, until she ate some peanuts one time, and ended up with a colostomy. When they got older, she and Frank found it hard living in the apartment, so they asked if they could live with me and Shirley, which was fine with us.

Cheryl: When we would get up in the morning to go to school, or to work, she would be sitting on the yellow stool in the corner of the kitchen, having her toast and tea. She was there every morning like clockwork. She would make me toast once in a while, and I would make her toast once in a while. She always told me she loved me. When she died, it was a tough thing to handle. I would get up, and she wasn’t there. She was a soft, caring, comforting grandmother. She loved to be around her grandchildren. She was a hard worker. She was always cleaning the house. She was well groomed, always wore a dress, and made you proud that she was your grandmother.

**************************

Also present at the interview were two of Mamie’s great-granddaughters, who watched and listened intently. One of them, Jennifer Begonis Ford, looked almost identical to Mamie, and I told her about it. The next day, she emailed me, and later followed up with some astonishing photos.

“You came to my mom’s house this past weekend to interview my grandfather, my mom and my aunt. Up until this point, I never knew who my great-grandmother was, and never knew of the beautiful photos of her. Now I have this overwhelming urge to learn more. Since meeting you, Mamie has consumed all of my thoughts. I went to your link to the Library of Congress website and printed all of Mamie’s photos. I also found some photos of myself when I was 12-14 years old, and I can’t believe the facial features that I share with Mamie. Please keep in touch, and thank you for opening my eyes to wanting to learn more about my wonderful, hard working family.”

Lewis Hine caption: Comparison of Ages: Left end, Marion Deschere, just passed 13 years. Helps sister in mill “some.” Next is Mildred Greenwood, “going on 14.” Goes to school. Next is Mamie La Barge, 13 years, but said 14 years. Right end is Rosina Goyette, said 14, probably 12 or 13. Mamie and Rosina have steady jobs. Location: Winchendon, Massachusetts, September 1911.

![Henry (with dog), Francis [Frank] (wearing hat), Odella (next to Francis), Mamie (next to Odella), Josephine (standing at left), Eglantine (next to Josephine), mother LaRose (seated next to Eglantine), and Louise.](https://morningsonmaplestreet.com/files/2014/11/MamieAndFamily11.jpg)

**************************

Onesime John Laberge: January 5, 1854 to September 26, 1944

LaRose Marie Branconnier Laberge: February 14, 1863 to October 5, 1915

Henry Arthur Laberge: February 23, 1881 to August 13, 1970

Marie Louise Laberge Laprise: January 31, 1883 to April 29, 1941

Josephine Laberge Beauchamp: July 24, 1885 to October 8, 1934

Joseph Onesime Laberge: March 28, 1887 to October 31, 1960

Roseanna Laberge Sumner: April 12, 1888 to September 23, 1944

Alfred Laberge: May 10, 1890 to June 23, 1935

Maude Laberge: February 17, 1892 to August 19, 1892

Agnes Laberge Bessette: April 7, 1894 to January 23, 1970

Eglantine Laberge Payette: February 14, 1896 to May 7, 2001

Mamie M. Laberge Mossey: February 12, 1898 to November 18, 1977

Odella M. Laberge Doyle: December 15, 1899 to May 20, 1987

Edward Francis Laberge: February 4, 1902 to December 14, 1988

Baby boy Laberge: January 6, 1903 (stillborn)

Baby boy Laberge: September 16, 1904 (stillborn)

***************************

A final surprise photograph

*Story published in 2011.