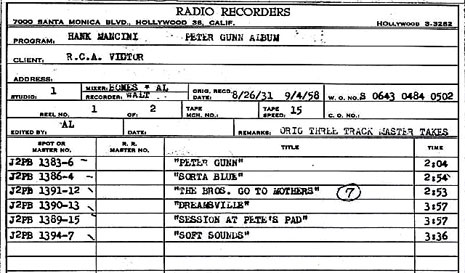

On a late summer evening in 1958, at Radio Recorders, a legendary recording studio in Santa Monica, California, a mild-mannered 34-year old conductor, pipe in mouth, gives the downbeat, and a guitarist, also 34 years old, starts grinding out a heavy, rolling ostinato. Two bars later, a curly-haired 26-year-old pianist makes his entrance, banging out the same line in unison. Suddenly, a raucous horn section jumps in, soon joined by a boisterous alto sax. In two minutes, it ends with one final gasp of energy. The groundbreaking Peter Gunn theme is in the can.

On a late summer evening in 1958, at Radio Recorders, a legendary recording studio in Santa Monica, California, a mild-mannered 34-year old conductor, pipe in mouth, gives the downbeat, and a guitarist, also 34 years old, starts grinding out a heavy, rolling ostinato. Two bars later, a curly-haired 26-year-old pianist makes his entrance, banging out the same line in unison. Suddenly, a raucous horn section jumps in, soon joined by a boisterous alto sax. In two minutes, it ends with one final gasp of energy. The groundbreaking Peter Gunn theme is in the can.

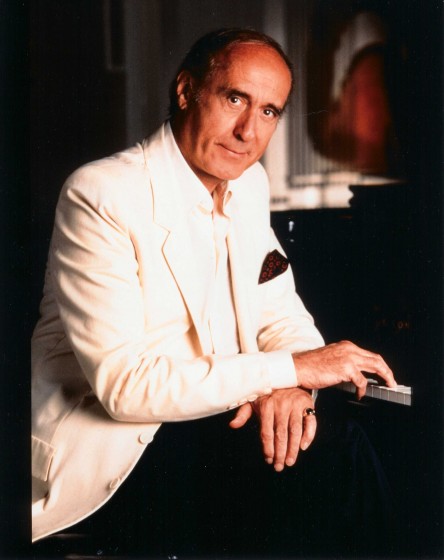

The conductor was, of course, Henry Mancini, soon to become the most innovative and influential film composer of the last 50 years. The guitarist was Bob Bain, a stalwart who cut his teeth in the Tommy Dorsey and Bob Crosby bands after the war. The alto player was Ted Nash, on his way to becoming one of Hollywood’s leading studio musicians. The pianist? It’s now a great trivia question. It was Johnny T. (Curly) Williams, who later shed his curls and made his mark as the one and only John Williams, forever linked with the films of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. Looking back at the TV show and the RCA album sessions, just about everyone connected with them built great careers on the strength of 40 minutes of music.

When NBC plugged Peter Gunn into the 1958 fall schedule, my father and I gave it a look and became faithful fans. I liked the background music, and for the first time, checked out Felix Grant’s famous Washington, DC jazz radio show on WMAL. I became a jazz fan for life. When I headed off to the University of Maryland a year later, I discovered a plush listening room at the student center, complete with an audiophile stereo system.

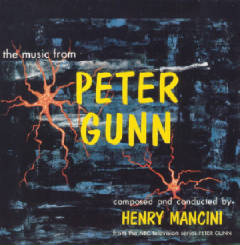

I dropped in one night and played The Music from Peter Gunn. It was my first stereo experience, and I was blown away, both by the sound and the music. Nearly 50 years later, Gunn is my all-time favorite album. I now have the 1988 BMG reissue on CD (serial number 1956-2-R), and it sounds exactly like it did to my 18-year-old ears, only better. Other reissues haven’t quite measured up.

Not Another TV Western

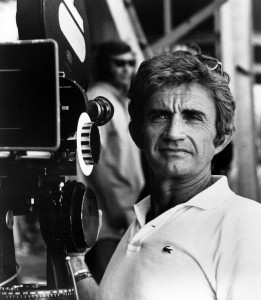

It all started with Blake Edwards, who had been knocking around the radio, TV and film industry as an actor, writer and director for more than a decade. He created the Richard Diamond, Private Detective radio series for Dick Powell back in 1949; and perhaps with that in mind, dreamed up the Peter Gunn character, wrote and directed a pilot, and landed a sponsor.

Mancini, who studied at Juilliard, had been working as an orchestrator and composer for Universal International Pictures since 1952, landing the job after a stint as pianist and arranger for Tex Beneke’s version of the Glenn Miller band. After scoring the Glenn Miller Story, for which he won his first Oscar, and the Benny Goodman Story, he worked with Edwards on several Tony Curtis films, Mister Cory and The Perfect Furlough.

In 1958, Orson Welles hired him to score Touch of Evil, a now-classic film that takes place in a town on the Texas-Mexico border. Welles wanted only source music, and Mancini obliged with a raunchy jazz-rock score that not only brilliantly evoked all the seedy, film noir ambience of the movie, but also helped to establish American jazz as a credible alternative to the European-Romantic style of film composing that had dominated Hollywood for 30 years.

Shortly after, Universal laid off most of its music staff, including Mancini. Then Edwards showed up with the Peter Gunn idea and asked Mancini to do the score. According to his book, Did They Mention the Music? Mancini accepted the invitation and walked away thinking it was just another TV western.

The premise of the show called for Gunn (Craig Stevens), a private detective, to spend much of his time at Mother’s, a nightclub where his girlfriend, Edie Hart (Lola Albright), sings with a jazz combo. So the use of jazz as source music was a natural choice; but when Mancini elected to score the action and dramatic scenes with jazz as well, he wound up giving the show its most identifiable and marketable quality.

In a recent interview, Ginny Mancini, Henry’s widow (he passed away in 1994), told me that her husband was “inspired by the cool romantic side of the relationship between Peter and Edie. He thought the music needed to be strong, sexy, and get your attention. He would sit down with Blake and spot where the music should come in and where it should go out and what it had to say. He pretty much had it in his head before he sat down at the piano.”

Ginny had sung with Mel Torme and the Meltones, and Tex Beneke, and she proved to be a valuable resource for her husband. “I was sort of a second pair of ears for him. If something he wrote reminded me of anything else, I’d tell him. He knew how well acquainted I was with the standards.”

By the time of the first recording session for the pilot episode, Mancini had written the famous theme, several tunes for the night club sessions, and some of the now-familiar cues for the action scenes. He also went into the studio to back Lola Albright on her recording of the old standard, “Day In, Day Out,” which was to be featured at Mother’s.

Interviews with musicians, sound engineers and others, and sound samples

Ronny Lang

When the call went out for musicians to do the music for the pilot, Mancini had decided on four woodwinds, four trombones, one trumpet, and five rhythm (piano, vibes, guitar, bass and drums). One of the first to get called was 31-year-old Ronny Lang, a sax and flute player who had worked with the Les Brown band for a few years. I managed to track down seven of the musicians, including Lang, who shared some memories.

“Les Brown did a concert in 1956 at UCLA with (film composer) Franz Waxman and a studio symphony orchestra. It was a joint concert that featured music by German composers, and one of the pieces was ‘Concerto Grosso for Symphony and Jazz Band’ It was a tour de force for alto sax. Hank was at the concert. After the concert was over, he came over to me and said, ‘I didn’t care much for the piece, but you did a great job.’ Soon after, I left Brown. I had to get off the road, because I had a couple of kids. I started to do a little bit of studio work. It wasn’t easy to break in. I would be called as a substitute occasionally.”

“When I walked into the studio for the Peter Gunn gig, I had no idea what kind of music we would be playing. When you’re a studio player, you show up, and sometimes the music is great, and sometimes it’s boring. Gunn was quite a breakthrough because he used jazz throughout the whole show. I thought it was exciting music. It wasn’t out and out jazz, but it had a strong beat.”

“I played a lot of the flute jazz (on the show), and Ted (Nash) played the alto sax. At that time, I had been playing the baritone sax with the Dave Pell Octet, and Hank needed a baritone player, so I played a lot of that also. When it came to the flute, Hank was very specific about what he wanted. He didn’t tell me exactly what to play, but he said, ‘Stay in the low register and don’t play too many notes.’ He wanted the jazz to be melodic, like you were playing a song, not just blowing up and down chord changes.”

“Hank wasn’t a taskmaster. He had come up as a band musician, and he was a very down-to-earth guy. I seldom saw him get angry. He got respect through his ability, and he was very personable. He wasn’t one for making a great many takes. Especially on jazz things, after one, two, or three times, it starts to get a little stale.”

“After that, I did more work for Hank, and worked with (film composers) Elmer Bernstein and John Williams, when he was called Johnny Williams. And I worked with (director) Martin Scorsese on Taxi Driver.”

“I’ve been trying to get hold of Scorcese for years. That was Bernard Herrmann’s score, and I played the alto sax solo. In those days, you didn’t get credit. A few years ago, I saw a television show that was a tribute to Herrmann. They interviewed Scorcese, and he was asked, ‘Was that an alto sax or a tenor sax?’ He obviously didn’t know. If I ever run into him, I want to tell him, ‘It was an alto sax, Martin, and it was played by Ronny Lang.’ I also worked a long time with John Barry, and that’s me playing the alto on his score for Body Heat.”

I’ll always be thankful to Hank, because working with him was the key for me to get into studio work. He had a contractor named Bobby Helfer. A contractor is the guy who actually hires the musicians for the leader. He was the contractor for all the Hollywood composers. Back in the 1950s, I was always trying to connect with this guy and get some work, but he used to hang up on me. After I did Peter Gunn, I was on his ‘A’ list.”

Gene Cipriano

Gene Cipriano, now 77 years old, played with Mancini in the Tex Beneke band, and he also got the call for Peter Gunn.

“He asked me, ‘How’s your flute playing?’ I had studied flute for about a year, but then I sold it to buy an oboe. I hadn’t touched a flute in about six months. He said he was going to do the pilot in a couple of months. I told him my playing was good, and then went out and bought a flute and woodshedded (intense practicing of fundamentals). When we did the pilot, there wasn’t much flute for me to play, just a lot of bass flutes as a pad, so it wasn’t too hard. Ronny played most of the flute solos and Ted (Nash) did the alto solos.”

“Two years later, we were doing Mr. Lucky with Henry. Tuesday night would be Lucky, and Wednesday night would be Gunn. Henry was a joy to work for – so relaxed – really a wonderful man. We had a lot of laughs. We looked forward to it.”

“Peter Gunn changed the whole scene on TV. Producers started asking for jazz. A lot of the young jazz composers got work, like Pete Rugolo and Lalo Schifrin and Dave Grusin. It opened up my opportunities enormously. When it caught on, people would ask for the guys in Henry’s sessions.”

“I worked with Elmer (Bernstein) and (film composer) Jerry Goldsmith. I even did a lot of rock work (he once played on a Frank Zappa album). I worked with Marty Paich on ‘Unforgettable,’ his last thing with Natalie Cole. I’m working tonight at Capitol. The phone is still ringing and I’m still fooling them.”

Dick Nash

Often called “Henry Mancini’s favorite trombone player,” Dick Nash was also an alumnus of Tex Beneke’s band, and worked with bandleader-arranger Billy May. Like his brother Ted, he was in Mancini’s band for Peter Gunn.

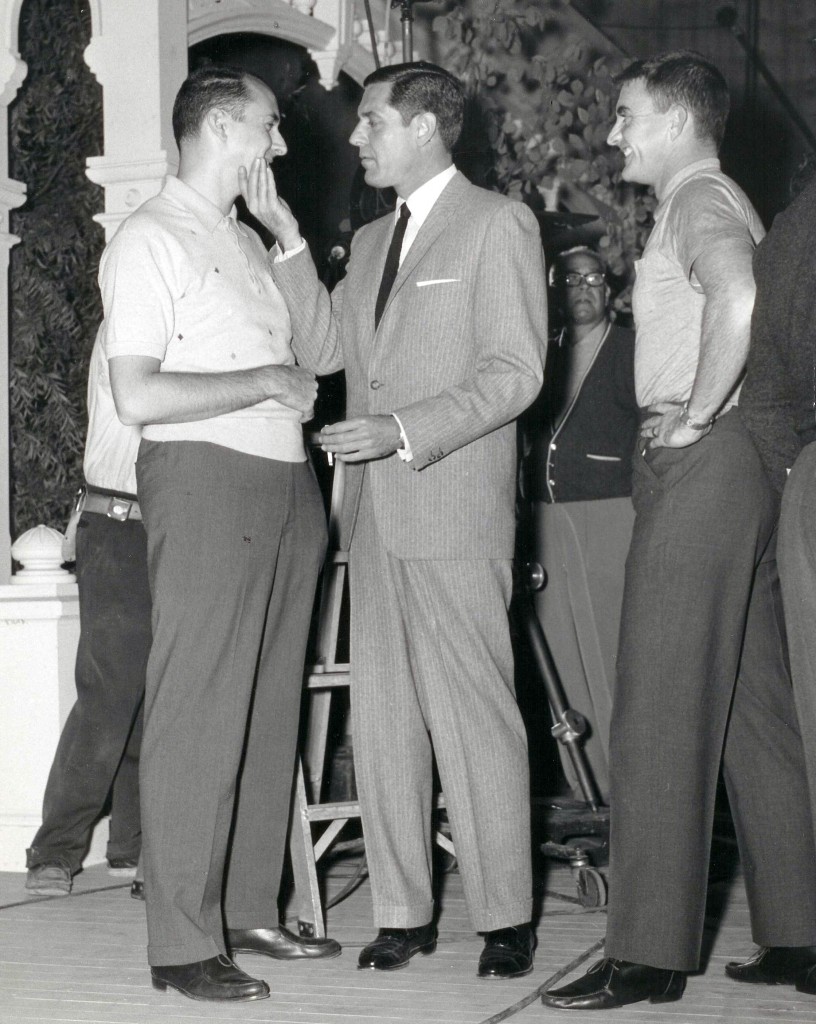

“I don’t think any of us saw the music. We just walked in, and there it was. We were very impressed. It was going to be a TV show, and to have all the good jazz guys in LA involved with it made for quite a get-together. We had Jimmy Priddy, John Haliburton and Karl De Karske on trombones, and Pete Candoli and Conrad Gozzo on trumpets. Milt Bernhart (trombone) did some sessions. And we had Johnny Williams. We called him Curly. He had a lot of hair then. I had the pleasure of working on many movies with him later.”

“When he would have a solo, Pete would really get the essence of what Hank was doing. And Gozz – we called him ‘gopher’ because he had no neck – it was an inspiration to sit behind him and hear him bore notes into your head. We reveled in what we were doing. It was something revolutionary, but we didn’t know it was going to be accepted.”

“There were four French horns and four trombones on ‘Dreamsville.’ We had to work on it to get that blend, and we had to get everybody miked properly to get that sound. The trombones put on a felt hat to lessen the edge, but the horn players, of course, had their hands in the bell.

I did some sidelining (appearing on camera on the show) on a couple of occasions, like on ‘The Brothers Go To Mothers.’ It was all pre-recorded. We’d just hold our horns up and fake it.”

“The talent Hank had for melody and harmony was just incredible. It was such a pleasure to play his music. Of all the people I’ve worked with, Hank had the best ear. He could nail second oboe. Other composers would have to hear the section to find out what was wrong, but Mancini could just nail it right away.”

“I think I did about 15 albums with Hank. He always wrote something for me. The first solo I did was on ‘Too Little Time,’ a ballad from the Glenn Miller Story. We got the chart out and ran it down, and I’m playing it sort of like Tommy Dorsey. Hank didn’t want to embarrass me, but he put down the baton, came down, and put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘Can you warm it up a little?’ That was a great thing for me, because I tended to play nine million notes in a bar that didn’t mean anything, and that helped me develop a thoughtful phraseology for myself. He was a big influence on my sound. He put me on the map.”

“Back in 1953, The Bad and the Beautiful (score by David Raksin) was in the theaters, and the MGM orchestra had put out a record on the theme. That was our theme song when my wife and I got married. We’d look into the jukeboxes on our honeymoon, and we rode across the country listening to that tune. We used to go to parties with David, and he would be at the piano playing that. He asked me to play the tune with him once, and that was a thrill.”

“I’m just about retired from the studios. I’m going to do the Academy Awards show, and I did a couple of things on a CD with Sammy Nestico. I’m going to be 79 soon, and I don’t need it.”

**************************

Others who were hired for the sessions were drummer Jack Sperling and bassist Rolly Bundock, both formerly with Beneke, and vibraphonist Larry Bunker. A year later, Williams got busy in films and was replaced by Jimmy Rowles. Sperling and Bundock joined The Tonight Show band and were replaced by Shelly Manne and Red Mitchell, and Bunker was sharing duties with Victor Feldman. All have since passed away.

It should be noted that fading memories and sloppy research has led to some confusing information about the personnel on the sessions. For example, the liner notes for one of the CD reissues names Barney Kessel, not Bain, as the guitarist, but everyone connected that I talked to said Kessel didn’t participate.

Bones Howe

Even before Peter Gunn had aired its first show, RCA was considering releasing an album of the music, no doubt on the strength of the powerful theme. Producer Simon Rady took an interest and suggested it to Mancini, who didn’t want any part of it, fearing that no one would know who he was, and the album would fail. Meanwhile, Blake Edwards took the theme to bandleader Ray Anthony, who had just scored a hit with the theme from Dragnet. Anthony released it (Mancini’s arrangement), and it was a smash.

According to Did They Mention the Music?, Mancini had a meeting with big-selling jazz artist Shorty Rogers, and tried to convince him to record the score, but Rogers threw it back and said, “It’s your baby, and you should do it.” So Rady went ahead and set up the recording sessions at Radio Recorders, where 25-year-old Bones Howe was working as an engineer. He wound up with the assignment. Howe told me that it was great opportunity, but it didn’t last long.

“I had been working at Radio Recorders for about two years. I started as an apprentice. In 1957, I started mixing. I had done a lot of jazz records, almost the entire Mode Records series, people like Richie Kamuca, Stan Levy, Jimmy Guiffre and Sonny Stitt, and the Marty Paich Octet. In those days, it was live to mono and two-track, so you could do a whole album in a day, because there was no mixing. I had done a lot of stereo recordings, because they had bought an Ampex 350 two-track. Most of the stereo records coming out at that time were what we called ping-pong stereo, you know, the bongos on one side and the tambourine on the other.”

“I was a drummer. When I was at Georgia Tech, I was playing six nights a week. I graduated with a degree in electronics and communication. I met Shelley Manne when he came through town, and he said to me: ‘You’re a musician, you know about electronics, and you should come to California and become a recording engineer. None of those engineers are musicians, so they don’t know what a rhythm section should sound like.'”

“So I moved to California, and met John Williams. He and I used to go out and play on jam sessions together. We were social friends. He started working at Universal and met Mancini. John played on the Peter Gunn sessions, and that’s probably how I got the gig. It was going to be done on two dates, the first with the big band, and the second with the small group. I did the big band tracks, but Si (Rady) was difficult to work with. He said to me: ‘This is going to be a big hit, and I want to cut a hot 45, so I don’t want to see the needle out of the red the whole time we’re recording.’ ”

“I told him that what we did in the studio only goes to the tape, so when he makes the record, he can make it as loud as he wants. If we overload the tape, it’ll be distorted. But he kept insisting on it. I had to protect the quality of the recording, so I kept the needle down. At the end of the date, he found out about it and he was furious. But we kept the tracks, and they ended up on the album. I went to the chief engineer and told him I wasn’t going to do any more sessions with Si. So they hired Al Schmitt for the small group recordings. He and I were good friends. He was the right guy to finish up that album.”

I told Howe that I liked the “live” sound of the album, that it felt like the music was being blasted out a window on a city street at three o’clock in the morning. He laughed and told me why.

“Let me tell you about that echo chamber we had. That chamber was a dream. I used the room and the directional microphones. I had played in a band, and I knew that the guys should be able to hear each other. I used RCA 77 DX microphones on the brass. I put two of them back to back and split the sax section so that three guys were facing two guys. I used at least two mikes on the drums. On the theme, Bob Bain had an amp, and it was clear that his guitar was an important part of the chart. So he was miked separately. That sound you liked – that was the sound of that Studio B echo chamber.”

“In those days, you could cut four tunes in three hours. Those kinds of sessions went really fast, because the guys that played were really great; they’d run it down twice, and they would have it. They had a powerhouse brass section, the guys from the Sinatra albums.”

“Everybody enjoyed working with Hank. It was the first time I got a chance to really know him. He was a sweetheart of a guy. I loved the music that Hank wrote, especially ‘Dreamsville.’ What a pretty tune that is. When someone put lyrics to it (Jay Livingston and Ray Evans), I tried to get Ella (Fitzgerald) to record it.”

Howe went on to engineer and produce many hit records for rock and pop groups such as the Association, the Turtles, the 5th Dimension, and singers from Johnny Rivers to Tom Waits, with whom he did five of his classic albums. He was chief engineer for the Monterey Pop concert film and Elvis Presley’s 1968 Christmas TV special, and music supervisor for films such as La Bamba and Back to the Future.

Bob Bain

As engineer Bones Howe alluded to, Bob Bain’s guitar was the driving force behind the Peter Gunn theme. After knocking around Los Angeles in the early 1940s, Bain joined Tommy Dorsey’s band, and also worked with Bob Crosby and Harry James. Later, working with arranger Nelson Riddle, he backed up Sinatra and Nat Cole. In fact, the famous guitar intro to Cole’s recording of “Mona Lisa” was created (but ultimately not played) by him.

On the theme, Bain told me that he used a 1953 Fender guitar. “It became a very well-known guitar, because it was built a little differently. It has a different bridge on it and a different pickup. I had mine modified a little bit. Hank wanted that special sound, so I didn’t play it open-stringed; I muffled it a little. Ever since that record came out, it’s been known as the Peter Gunn Guitar.”

“On the record, I remember playing the bridge to ‘Dreamsville.’ I had never heard that tune before, so I just sight-read it. I made that long gliss (glissando – sliding up from one note to another) to get in position to play the rest of it. Every time I run into some guitar player, he’ll say, ‘I liked the way you played that gliss.’ At the time, I wasn’t even aware of it.”

When he was called for the session, Bain had worked with Mancini quite a bit already. “Dominic Frontiere and I did Hank’s first album, on Liberty Records (The Versatile Henry Mancini). It was just accordion and guitar, and Hank had written these Italian-style arrangements. We were always laughing, because it was just two guys and a leader playing an album of Italian street songs. I also worked with him on several films: Rock Pretty Baby and Touch of Evil.”

“Another guitarist, Tommy Tedesco – he was a fine player and a good friend – did some sidelining on the show. Sidelining never paid much, and you could spend all day on the set just waiting to go on. I never did it. So Tommy does the first show where the combo is playing at Mother’s. A couple of days before it runs on TV, he calls everybody in his hometown of Buffalo and says, ‘Watch Peter Gunn. That’s me playing.’ It wasn’t, of course; it was me.”

“We had a lot of fun on those sessions, doing the cues for the weekly shows. On the tens (10-minute breaks mandated by the musicians union), we played touch football in the alley next to the building: Dick, Ted, Cip (Cipriano) and I. We’d go in at 8:00 in the evening and finish by 11:00 – and make 90 bucks.”

“Then Hank started doing all those great pictures, and he was using the same guys. I used to get calls from people I didn’t know, and they’d ask, ‘Are you Mancini’s guitar player?’ We worked together for a long time, and then I got hired for the Tonight Show.”

Al Schmitt

At the next session, Mancini and the gang found Al Schmitt at the controls.

“I had just moved out from New York,” Schmitt told me. “They had wanted that big sound on the first date, but when they recorded the small group numbers, they wanted a more intimate sound. Everybody was really happy with it. Hank was the easiest guy in the world to work for. He’d get everything set up and then light up his pipe.”

“In those days, if you went even one minute overtime, you had to pay the musicians for a half-hour more. Right at the end of the date – Hank was famous for this – we’d get down to about three minutes before the end of the session, and the producer would say, ‘OK, Hank, that’s great. We got it.’ And Hank would say, ‘No, we’ve got to do one more take.’ And we would go one or two minutes over, and then we’d wind up using the take before. That was his way of saying thank you to the musicians. He gave them that extra half-hour. He was a wonderful guy, with a great sense of humor. And he was a brilliant arranger.”

“RCA had no idea what they had when they put that record out. It just flew off the shelves to the point where they had to sell the record in generic covers, because they didn’t print enough covers. People had to come back to the record store and get the real cover two weeks later. I started doing all of the Mancini records: More Music from Peter Gunn, Mr. Lucky, Breakfast at Tiffany’s (Grammy nomination) and Hatari (Grammy).”

Schmitt went on to win 15 Grammys (so far), and has engineered for everyone from Jefferson Airplane to Diana Krall, and Sinatra to Streisand.

Cipriano told me he was in awe of Schmitt’s talents. “Al was great. He got a sound on the bass flutes that still hasn’t been duplicated. I don’t know how he did it. That’s a soft kind of instrument, and he had us way out front.”

I asked Schmitt if he remembered that John Williams was in the sessions.

“Sure. He was a sweet guy. He had rosy cheeks. The last time I saw him, I said, “You’re big now, but in those days, I could get John Williams for three hours – and for just 42 bucks.”

A Look Back at the TV Series

I recently bought the two DVD sets of the first season of Peter Gunn. I hadn’t seen the show since it ended in the early 1960s. It was a weird experience. For starters, each show winds up being about 24 minutes, since there are no commercials. Too bad; it would have been fun to see them, too. The opening show, called “The Kill,” established the typical format, practically carbon-copied for every episode thereafter.

I recently bought the two DVD sets of the first season of Peter Gunn. I hadn’t seen the show since it ended in the early 1960s. It was a weird experience. For starters, each show winds up being about 24 minutes, since there are no commercials. Too bad; it would have been fun to see them, too. The opening show, called “The Kill,” established the typical format, practically carbon-copied for every episode thereafter.

When the show opens, we hear a walking bass on the soundtrack, followed by growling trombones and thunderous low piano chords. Two cops pull a car over, then shoot the occupant. It’s very film-noirish: dark streets, neon signs, big sedans, dour men in suits. The driver collapses on the horn, and it blares interminably as the cops pull away. Then the credits roll and the theme blasts for 15 seconds.

In the next scene, Gunn is at the victim’s funeral (he was a mob boss) and runs into police detective Lt. Jacoby (Hershel Bernardi), who asks rudely, “What are you doing here?” That’s one half of the essence of their relationship – private detective getting his nose in police business – the other half being mutual respect and an understanding that they often depend on each other for information.

When the funeral is over, some gangsters threaten Gunn, and we’ve figured out now that they were the phony cops who rubbed out the boss, so they can take over leadership of the gang. Bluesy, unobtrusive music plays in the background, adding a sense of uneasiness. In the next scene, Gunn drops into Mother’s. The combo is playing what was to become “Brief and Breezy” on the album.

Confirming Bain’s story, there’s Tommy Tedesco acting like he’s playing the guitar. We meet Mother (Fay Emerson), the club owner, who is worldly and street smart. Up steps Edie at the mike, and we hear her sing a lightly swinging version of “Day In, Day Out,” as the camera zooms in on the seductive smile she flashes at Gunn. Then one of the gangsters walks in and buys a drink.

After the song, Gunn goes up the stairs to the roof, and Edie soon follows. It will prove to be a popular hangout for them. This is where Blake Edwards shows us the nature of their love affair – he’s always off working on a case, and she gets stuck alone. Their conversation is full of wisecracks, much like the banter between Cary Grant (actor Stevens is almost a dead ringer for him) and Eva Marie Saint in North By Northwest, or any movie with Bogie and Bacall. We hear a tune faintly from the club downstairs, and it later shows up on the album as “Slow and Easy.” It is.

Gunn goes to visit the gangsters, accompanied by the walking bass, a snaking alto flute, and a few horns jumping in and out. A fight finally breaks out, and the music screams as the scene fades to Mother’s, where Edie stands by the piano while Emmett (Bill Chadney, who later married Lola Albright) improvises a soft blues. Of course, it’s really John Williams on the soundtrack. For me, the closing-time ambience of this scene is one of the best moments in the show.

Several more violent scenes follow, culminating in the obligatory gun battle, while more tense jazz fills the soundtrack. In the final scene, Edie is singing “Day In, Day Out” again as Gunn looks at her longingly. Then we fade to the theme and closing credits, this time, 40 seconds long.

I watched all 32 episodes over a period of about two weeks. The formulaic and predictable plots and resolutions are oddly comforting, if not very artful. And they were certainly filmed on the cheap. Two things make it highly entertaining, one being the well-drawn characters and underplayed acting, especially from Lola Albright, who, like Bette Davis, steals every scene she’s in with just the bat of an eye. The other is Mancini’s music, which gives it life. In fact, you come away with the feeling that the whole thing was created to fit the music, and that the actors are speaking their lines rhythmically, as if they were lyrics to a song.

About the weekly soundtrack sessions, Bain remembers, “The music was always good. Hank wrote so well. You never knew what you were going to run into. On some of those cues, all we had to do was play 20 or 30 seconds, but they were interesting.”

In subsequent episodes, that proves true. Just when you think you’ve heard it all before, the composer comes up with a fresh idea, like an unusual combination of instruments, something he remained well known for his entire career. For instance, in “Pecos Pete,” a show on Disc 3, a 30-second cue leading up to a murder is underscored by a twangy, insistent guitar riff, a heavy rock beat banged out on the drums, and a some menacing saxes. It’s fun, and it works. And there are surprises for devoted Mancini fans. In several shows, a pianist plays a haunting tune that later became “White On White,” which is on the soundtrack to Experiment In Terror.

Revisiting the RCA Album

Mancini appeared to have an intuitive sense of the record business, exemplified in part by his choice to avoid the typical soundtrack album format of the 1950s, that is, to string together 30 to 45 minutes of dramatic cues directly from the film. It was his notion that the albums would be more interesting to the casual listener if he fleshed out the cues into completed songs and re-recorded them in the studio, where he could take advantage of the latest stereo recording technology. Breakfast at Tiffany’s and The Pink Panther were perfect examples, and so was The Music From Peter Gunn.

Mancini appeared to have an intuitive sense of the record business, exemplified in part by his choice to avoid the typical soundtrack album format of the 1950s, that is, to string together 30 to 45 minutes of dramatic cues directly from the film. It was his notion that the albums would be more interesting to the casual listener if he fleshed out the cues into completed songs and re-recorded them in the studio, where he could take advantage of the latest stereo recording technology. Breakfast at Tiffany’s and The Pink Panther were perfect examples, and so was The Music From Peter Gunn.

So what makes this album such an enduring winner? After many hundreds of listens over the years, I’ve tried to step back a bit and figure out what catches my ear.

Obviously, the theme is a high point. With this and several other big band tracks, Mancini augmented the band with three more trumpets, Candoli being the only one on the small group sessions and the TV cues. Most sources indicate that the other three were Gozzo, Frank Beach and Uan Rasey. There were also four French horns: Vince DeRosa (the lead), Richard Perissi, John Cave and John Graas. They perform the famous “scoop,” where they provide counterpoint by repeatedly sliding up an octave.

Although the forceful, sinister-sounding tune hangs on one chord, it impresses me as one of the most powerful big-band recordings I’ve ever heard. Still, Ginny Mancini told me that her husband could never understand why it remained so popular, often commenting to her that, “So much has been made of so little.”

Now in his eighties, DeRosa had a long and fruitful career playing with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Nelson Riddle and Gordon Jenkins on the Sinatra albums, and with Alfred Newman at 20th Century Fox for 20 years. He’s the one playing Mancini’s mournful theme on the soundtrack at the end of Days of Wine and Roses. He remembered the Peter Gunn sessions and recalled:

“I did many albums with Hank. He was unique. He’s probably one of the biggest talents that ever hit Hollywood. He could write a good melody. Any session with a man of Mancini’s stature was a good session.”

Rasey, who’s the man on the trumpet in Goldsmith’s haunting theme to Chinatown, had already worked with Mancini on several pictures at Universal. Also in his eighties, he pointed out: “Hank was an original. I remember that he liked to use bass flutes and alto flutes, and he used a lot of flatted fifths.”

The next track, “Sorta Blue,” is a catchy minor-key blues with a bridge that’s sort of a throwaway, an often-used device in Mancini’s bag of tricks. He introduces one of his signature styles here, having the vibes play the melody in unison with a horn. There’s some nice solo work by Lang (baritone) and the Nash brothers. But it’s Candoli’s showy upper-range solo that puts the tune in high gear.

Ultimately, it’s Candoli’s slightly loose-cannon work that colors the album and supplies its overall mood, especially on the high-energy numbers. As Cipriano said, “Hank had to calm down Pete a few times.” Candoli himself told me, “Hank gave me quite a bit of liberty. He just told me to stay in the middle register, then play the high notes in the climax.” Known for his expressive style, Candoli goes back the Dorsey days, and was one of the stars of the Woody Herman band in the forties. He backed Sinatra on the Billy May and Riddle sessions, and was featured on Bernstein’s jazz score for Man with the Golden Arm.

Following “Sorta Blue” is one of Mancini’s most appealing mid-tempo tunes, “The Brothers Go To Mother’s,” which appropriately has brothers Dick and Ted playing the melody in unison, and then trading solos.

Things slow down with “Dreamsville,” clearly a landmark effort by the composer and perhaps his finest moment. There’s some gorgeous, moody ensemble brass work, the signature piano intro, a lovely solo by Ted Nash, and Bain’s famous “gliss” in the bridge. It’s the only tune I didn’t hear in the shows, so it was probably written especially for the album.

“Session at Pete’s Pad” picks up the pace. It has a great vibe solo by Bunker, and some wild blowing by Candoli. “Soft Sounds,” which is often heard during Pete and Edie’s romantic conversations, is sort of a lounge tune reminiscent of the George Shearing Quintet, with a Shearing-like solo by Williams.

Next is “Fallout,” which led off Side B on the LP with a bang. It’s a stunning arrangement based on the familiar walking bass opening on the show that signals that a crime is about to take place. In a series of half steps, it builds frantically to a crescendo, with Candoli’s piercing horn leading the way. In my interview with Pete, he expressed his enthusiasm for this piece, singing it as he described it in detail.

The unusual melody for “The Floater” has an almost two-octave range, bounces along to finger snaps, and sports a cool Charlie Christian-like solo from Bain. The lazy swing of “Slow and Easy” reminds me of Basie during his Neal Hefti days. I like the moaning bass trombone solo (is that Milt Bernhart?).

The final three numbers, “A Profound Gass,” “Brief and Breezy” and “Not From Dixie,” are slight of melody and feel like an extended jam session. They were probably written as source music for Mother’s. But it’s a nice, relaxing way to finish off the album.

Despite the record’s popularity and the strong reputations of the musicians in the band, there were some barbs thrown at it by jazz critics who sneered at the so-called easy-listening approach and Mancini’s questionable jazz credentials. Ginny comments: “He never considered himself a jazz artist to begin with. He was well rounded, and incorporated the jazz feel whenever it was appropriate.” Ironically, Mancini was to receive another Grammy in 1960 (he was awarded 20 altogether) for Best Jazz Performance for the album The Blues and the Beat, which he arranged and which included virtually the same players.

Comparing the album to the music on the show, I feel let down that there aren’t any recordings directly from the soundtrack. Though most of the cues are very short and are often repeated with only the slightest of variations, listening to them offers a chance to hear some of Mancini’s most interesting work. Even the abbreviated songs by Albright with the combo are appealing, and are much more genuine and effective than Dreamsville (out-of-print), the album she did with Mancini in 1960. Is there some producer out there who would like to issue a remastered box set of cues and songs from the show?

The Music from Peter Gunn topped the charts for quite while, being one of the hottest albums of 1958 and 1959. Ginny Mancini said it literally turned their lives around.

“The album had been made and the show had gone on the air. The whole music department had been let go at Universal. Hank and I had promised each other that we would take our first trip to Europe, and that we would go for six weeks first class. We had no guarantee that we would have more than ten cents in the bank when we got back. The whole thing with Peter Gunn happened while we were gone, and when we came back, we found out that we didn’t have to worry about the ten cents in the bank.”

Soon after, it won the first Grammy for Album of the Year. Like others I interviewed, Ginny said it created tremendous opportunities for jazz and popular music composers who wanted to work in films.

“It opened doors for guys like Michel Legrand, Quincy Jones, Nelson Riddle and John Williams. And his music had an influence on them. I know that John was influenced, because when he scored Catch Me If You Can, he said, ‘When I looked at this picture, I said to myself: ‘What would Mancini do?’ ”

A version of this article appeared in the June and July 2007 editions of Film Score Monthly.

Here are some sound samples, each corresponding to a particular musical highlight I noted in the article.

1. Peter Gunn Theme: a guitarist starts grinding out a heavy, rolling ostinato. Two bars later, a pianist makes his entrance, banging out the same line in unison. Suddenly, a raucous horn section jumps in.

2. Fallout! (Ronny Lang’s flute): “When it came to the flute, Hank was very specific about what he wanted. He didn’t tell me exactly what to play, but he said, ‘Stay in the low register and don’t play too many notes.’ He wanted the jazz to be melodic, like you were playing a song, not just blowing up and down chord changes.

3. Dreamsville (horns): “There were four French horns and four trombones on ‘Dreamsville.’ We had to work on it to get that blend, and we had to get everybody miked properly to get that sound. The trombones put on a felt hat to lessen the edge, but the horn players, of course, had their hands in the bell.

4. Dreamsville (Bob Bain’s guitar solo): “I remember playing the bridge to ‘Dreamsville.’ I made that long gliss (glissando – sliding up from one note to another) to get in position to play the rest of it. Every time I run into some guitar player, he’ll say, ‘I liked the way you played that gliss.’ ”

5. Brief And Breezy: In the next scene, Gunn drops into Mother’s. The combo is playing what was to become “Brief and Breezy” on the album.

6. Slow And Easy: Their conversation is full of wisecracks, much like the banter between Cary Grant (actor Stevens is almost a dead ringer for him) and Eva Marie Saint in North By Northwest, or any movie with Bogie and Bacall. We hear a tune faintly from the club downstairs, and it later shows up on the album as “Slow and Easy.” It is.

7. Peter Gunn Theme (scoop): There were also four French horns: Vince DeRosa (the lead), Richard Perissi, John Cave and John Graas. They perform the famous “scoop,” where they provide counterpoint by repeatedly sliding up an octave.

8. Sorta Blue: “Sorta Blue,” is a catchy minor-key blues. He introduces one of his signature styles here, having the vibes play the melody in unison with a horn.

9. The Brothers Go To Mother’s: …one of Mancini’s most appealing mid-tempo tunes, “The Brothers Go To Mother’s,” which appropriately has brothers Dick and Ted trading solos.

10. Dreamsville (Ted Nash solo): Things slow down with “Dreamsville,” clearly a landmark effort by the composer and perhaps his finest moment. There’s a lovely solo by Ted Nash.

11. Soft Sounds: “Soft Sounds,” which is often heard during Pete and Edie’s romantic conversations, is sort of a lounge tune reminiscent of the George Shearing Quintet.

12. Fallout! (Pete Candoli solo): In a series of half steps, it builds frantically to a crescendo, with Candoli’s piercing horn leading the way. In my interview with Pete, he expressed his enthusiasm for this piece, singing it as he described it in detail.

13. Floater: The unusual melody for “The Floater” has an almost two-octave range, and bounces along to finger snaps.

LINKS

Henry Mancini’s website

Pete Candoli’s website

Bones Howe’s website

Film Score Monthly

RECOMMENDED RECORDINGS

Juntos – The Nash Brothers, Fresh Sound Records

Basie Street – Ronny Lang and his All-Stars, Fresh Sound Records

First Time Out – Gene Cipriano, available from ResortMusic.com

Any Henry Mancini album, especially:

The Blues and the Beat, and soundtracks to Experiment In Terror, Hatari, The Pink Panther, Breakfast At Tiffany’s, Charade, The Molly Maguires, The Hawaiians and Sunflower. Some may be hard to find as CDs.