“Paint us an angel with the floating violet robe and a face paled by the celestial light; paint us a Madonna turning her mild face upward, and opening her arms to welcome the divine glory, but do not impose on us any esthetic rules which shall banish from the reign of art those old women with work-worn hands scraping carrots, those rounded backs and weather-beaten faces that have bent over the spade and done the rough work of the world, those homes with their tin pans, their brown pitchers, their rough curs and their clusters of onions.”

“It is needful we should remember their existence, else we may happen to leave them out of our religion and philosophy, and frame lofty theories which only fit the world of extremes. Therefore, let art always remind us of them; therefore, let us always have men ready to give the loving pains of life to the faithful representing of commonplace things, men who see beauty in the commonplace things, and delight in showing how kindly the light of heaven falls on them.” -George Eliot, English novelist and journalist

In the fall of 2005, I was hired by author Elizabeth Winthrop to find the descendants of Addie Card, a 12-year-old cotton mill worker in Pownal, Vermont, who had been photographed by Lewis Hine in 1910, for the National Child Labor Committee. Hine, who died in 1940, was one of the great documentary photographers of the 20th century.

Winthrop had recently completed Counting On Grace, a novel inspired by Addie’s photo. But she wanted to find out the real story of Addie, who had been identified by Hine as Addie Laird. Previous attempts by others had come up empty. Amazingly, Winthrop was able to quickly determine that Addie’s last name was actually Card. With that information, she learned that she had married at 17. But after the 1920 census, Winthrop could find no record of Addie or her husband, or if they had any children. That’s when she turned to me for help.

Within two weeks, I had located and contacted Addie’s granddaughter. In two more weeks, I was standing before Addie’s grave. Just after Christmas, Elizabeth and I met and interviewed Addie’s great-granddaughter, descended from the adopted daughter of Addie’s second marriage.

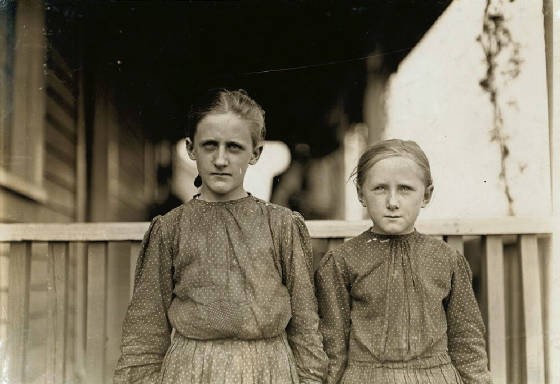

As the summer of 2006 approached, I learned that more than 5,000 of Hine’s child labor photos are viewable on the Library of Congress website. I waded through some of them one morning. I stared at the children, and they stared back. I said to myself, “I can do for these children what I did for Addie.” The first photo I picked out was the one above. Hine identified the girl on the left as Minnie Carpenter, but he did not give us the name of the other girl. His full caption was: “Oldest girl, Minnie Carpenter, House 53 Loray Mill, Gastonia, N.C. Spinner. Makes fifty cents a day for 10 hours. Works four sides. Younger girl works irregularly.”

After several weeks of research, I found Minnie’s death record, and obtained a copy of her obituary. She had died in 1973, single with no children. A nephew, Cramer McDaniel, also of Gastonia, was listed as one of the survivors. In the Internet White Pages, I found a man with the same name living in Gastonia. I called him, and he was the right person. He expressed great surprise about the photograph, and was very pleased when I told him I would send him a copy. I thanked him, dropped the photo in the mail, and called him three weeks later. He said excitedly: “I was hoping you would call me sooner. I’ve got some incredible news for you. The other girl in the photo is my mother Mattie.”

Why did I create the Lewis Hine Project?

Back in the 1960s, I was taking an American history course in college, and it occurred to me that the reason I was so bored with it was because I couldn’t identify with the people I was reading and learning about. As far as I knew, no one in my family was ever a general, or a president, or a senator, or a railroad magnate, or some other famous or privileged person (mostly rich white men). As the saying goes, we were just plain folks. I thought to myself, “Didn’t history happen to ordinary people, too?”

In 2002, I took a course in genealogy at a local college and went to work exploring my family history. I found out a bunch of amazing stuff. My father’s maternal grandparents married at age 17, left their homes in Indiana in a covered wagon, and headed slowly to Kansas to look for a place to farm. They eventually had nine children, four of them destined to die in their first year. My father’s paternal great-grandfather came to the US (Illinois) from Ireland in the 1830s, and lost five of his six sons in the Civil War. Both my father and I were named after the only son who survived. That was history I could relate to.

The children and families depicted in the child labor photographs of Lewis Hine were unwittingly caught in the act of making history, but we know almost nothing about them. The pictures were taken for a noble purpose, but a century later, they have become an enormous photo album of the American family. By finding out what happened to some of them, and by revealing the photos to their descendants (most descendants are unaware of them), we are dignifying their lives, and the lives of everyone that history has forgotten.

I am well aware that the mostly anecdotal information from descendants may have relatively limited historical value, since some important details will be left out, due to faded memories or an occasional unwillingness to mention embarrassing or deeply personal events. I also understand that the child laborers for whom I have been successful may tend to represent those who left the most easily followed trail, such as those who lived long enough to get a Social Security number, or serve in the military, or marry and have children. And I have come to realize that I often select children with “searchable” names, such as Archie Love, Shorpy Higginbotham and Ora Fugate; or that I may favor photos that are compelling simply because of their artfulness or because of the way they touch me emotionally.

But my aim here is not to write definitive biographies of each child, nor to establish any trends, nor to come to any conclusions about how the experiences of child labor affected their adult lives, nor to even make an informed argument for or against the practice of child labor. The stories, however long or brief, help us to get to know a few people whose only public persona has been a simple snapshot.

How do I track down the descendants?

Experienced genealogists and trained researchers are familiar with the tools I use to find the descendants. It’s essential to have access to the Internet, and a website such as Ancestry.com, which has a huge database of searchable digital records.

I usually choose a photo that has at least one person named in the caption. Hine did not always identify the children, and when he did, he often misspelled names. He frequently gave the likely ages of children, and virtually all of his captions list the location, and the year and month the photo was taken. The first thing I do is look in the US census to see if anyone with that approximate name and age was listed in the city, town or state where they were photographed. If I find the person, I try to follow them up through the 1940 census, the most recent one that is currently accessible to the public. This information helps to establish the year and place of birth, and the names of their parents, siblings, spouses and children.

If the person died with a Social Security number, their death record will appear in the Social Security Death Index. Once I know where and when they died, there is a good chance that I will be able to obtain a copy of the obituary in the newspaper archives at the library in the city or town in which they died. Most libraries provide this service, and will mail out obituaries for a nominal fee. The obituary usually lists some of the surviving family members, and often the town they were living in at that time. At that point, I search for the survivors in the Internet White Pages, or on one of the major search engines. If I am succcessful, I contact them.

There are major obstacles I constantly encounter. Some people just don’t get listed in the census. Some died very young and left no survivors. Many immigrants changed the spelling of their names, or the census takers (or Hine) hopelessly misspelled their names. And the biggest obstacle is finding the death records of girls, since those who married usually died with a different last name, which I won’t know unless I am lucky enough to find a state marriage record. If I get stumped, I pick out a male sibling and track him instead.

In a few cases, I have chosen a child who was not identified by Hine, persuaded the newspaper in the city or town where the child was photographed to publish the photo, and then waited to see if any readers recognized that child. This has proved to be a very effective tool, as you will note from some of the stories on this site.

That’s the short answer to this question. There is much more to tell.

What are my plans for the Lewis Hine Project?

Because I am an author, I have tried several times to find a publisher that would be interested in a book, but to no avail. A documentary film, perhaps in the style of those on Public Television, would be a terrific way to tell some of my stories, and my role in the project as well. But that has not materialized as yet. A third idea would be a traveling exhibition, similar to those sponsored by museums such as the Smithsonian, but so far, that hasn’t happened either. I work on this project essentially by myself, and at my own expense. Meanwhile, I happily post all of my stories on my website for anyone to see free of charge.

There are almost 5,000 child labor photos to choose from. I can’t do all of them. So when do I plan to stop?

That’s not likely to happen. The most rewarding part of this project has been having the opportunity to contact descendants who were not aware of the photos, and send copies to them (free of charge). Many of these descendants have never seen photos of their parents or grandparents as young children, and each new photo I choose brings the hope of finding yet another surprised and delighted descendant, and another story. Why should I stop now?