Knowing my penchant for hyperbole, my best friend is fond of saying, “I’ve told you a million times not to exaggerate.” Well, here I go again. Andre Previn may be the greatest all-around musician since the advent of recorded music.

Born in Berlin in 1929, he escaped Nazi Germany with his family and emigrated to Los Angeles when he was ten years old. Despite being schooled as a classical pianist, he started moonlighting as a self-taught jazz pianist as a teenager, after hearing some Art Tatum records. His father, a conductor in Hollywood, helped to get him a job as a staff arranger for MGM. By the time he was 18, he had already written several film scores, and become a popular jazz recording artist, even playing briefly with the great saxophonist Lester Young.

In the 1950s, with Shelly Manne, Leroy Vinegar and later, Red Mitchell, he put out some of the best piano trio records of the era, most notably My Fair Lady, the first jazz album devoted to a Broadway score. At the same time, he was making some fine chamber music recordings, becoming a highly respected interpreter of Mozart, Debussy and Gershwin.

How he still found time to write a dozen or so film scores is a mystery, especially since they were among the best of this time period. His moody, tense score for Bad Day at Black Rock, and his landmark jazz score for The Subterraneans are prime examples.

Continuing into the 1960s, he contributed his finest scores: the bittersweet Two for the Seesaw, the epic Four Horseman of the Apocalyse, and the delightful Irma La Douce, for which he received an Oscar. Somehow, he managed to slip off to the studio and put out a series of lovely “mood music” albums, featuring his jazz piano backed by his striking string arrangements.

Then he chucked it all for the concert hall, vaulting into the upper echelon of conductors, as he led the Pittsburgh Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, and London Symphony Orchestra, and ran up a huge catalog of recordings, including many of his own concert works. And just for kicks, he wrote three musicals, one a Broadway production starring Katherine Hepburn, and did an album with Ella Fitzgerald.

In the 1990s, he returned to jazz and recorded some great sets with the likes of Herb Ellis, Joe Pass, Mundell Lowe and Ray Brown, and later, several marvelous duo recordings with bassist David Finck. Oh yes, and he also wrote a highly praised opera based on A Streetcar Named Desire, while continuing to make classical recordings, both as a conductor and a performer. Need I say more?

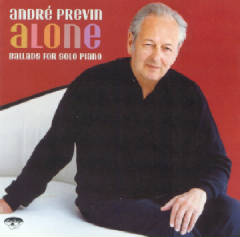

Now, at age 77, he has released Alone: Ballads for Solo Piano, and it’s one of the most beautiful jazz piano albums I’ve ever heard.

Previn has always been an underrated jazz pianist. Because of his astonishing versatility and the fact that he has never lived the “jazz life,” he has always been eyed suspiciously by the jazz community. In fact, his Tatum-like virtuosity, and his wildly unique and often playfully humorous piano style has made him one of the most interesting, creative, and entertaining jazz pianists around. But like Rodney Dangerfield, he never gets any respect. Thus, even his kindest critics are likely to throw darts at this latest release, perhaps calling it too sweet and not swinging enough. But there’s much more to this CD than initially meets the ear.

First, it is consistent with what I have always detected in Previn’s playing and writing: a deep sense of melancholy. You hear it in his film scores, the angular, bluesy tunes and sudden melodic leaps; and in his piano chord voicings, his choice of harmonic intervals, and his pervasive use of legato and rubato. Listening to Alone with one ear fills up the room with yearning and nostalgia.

But listening with both ears – try it in the car when there are no distractions – you hear so much more. This is particularly evident in his stunning interpretation of Rodgers and Hart’s “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered.” After a shimmering statement of the little known verse (Ella sang it this way), he develops the long melody line with dazzling twists and turns and seamless modulations. It’s a tour de force all the way.

Another dazzler is “What Is This Thing Called Love.” He tears up this song with so many wild ideas, that you wonder what he was thinking. No melancholy here; more like Monk or Jessica Williams. “Night and Day” falls into this category as well, highlighted by wonderful dissonances and Bill Evans-like tone clusters. On “I Can’t Get Started,” he closes with an unexpected blues cliché that is both funny and liberating.

Among the sweetest performances, Kurt Weill’s “My Ship” is a standout. What a gorgeous tune this is, and Previn knows it, feels it, and expresses it. The same can be said for “Angel Eyes,” where he apparently salutes Sinatra by opening with the bridge (Frank did on his Only the Lonely album).

Not surprisingly, it’s two of Previn’s compositions that are the most memorable. The short and simple “Darkest Before the Dawn” is from his relatively obscure 1974 musical Good Companions, written with Johnny Mercer. The only other known version is by Judi Dench, from the original cast album, now out of print. This song deserves attention.

And rounding out the CD is “You’re Gonna Hear From Me,” his classic song from Inside Daisy Clover, the 1965 Natalie Wood film. This is reportedly a Previn favorite. He recorded another solo version for What Headphones, his 1993 masterpiece on Angel Records. The song has aged well. Though it was belted out with bravado in the film, as the title suggests, the composer plays it with a sense of resignation, and the plaintiff melody deserves this treatment. The tune reminds me of Billy Strayhorn’s work, and belongs in the company of the Ellington sidekick’s best songs.

Alone lives up to its title. Previn sounds like he’s playing in his living room late at night, perhaps reflecting on his more than sixty years of turning out amazing music. I hope he has many more accomplishments ahead of him.

Alone: Ballads for Solo Piano, by Andre Previn, Universal International Music (B0009092-02)