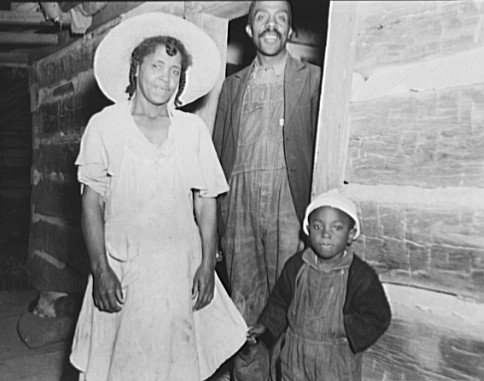

John Vachon caption: Nat Williamson with wife and one child. Guilford County, North Carolina, April 1938.

In April and May of 1938, John Vachon was in his second full year as a traveling photographer for the Farm Security Administration (FSA). While on the road in Georgia, he would have celebrated his 24th birthday, perhaps by himself in a small downtown hotel, his camera and equipment piled in the corner of the room. He kept a journal, and on June 4th of that year, he wrote:

“I still draw the low salary I drew a year and a half ago, $105 a month. I have made two photographic trips this spring – one to North Carolina and one to Georgia. I have some feeling for photographic work, though I think our particular brand a little over-rated. I might be able to do something with it sometime, that is something worthy, something of value. There, as in everything my life long, I need a theme.” -quote from John Vachon’s America, edited by Miles Orvell, University of California Press. Used with permission.

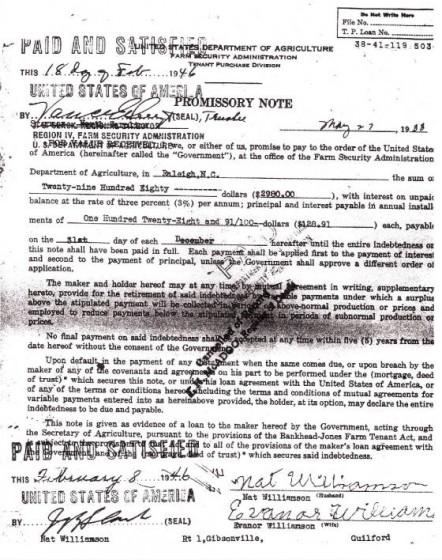

In retrospect, a series of photos he took that April of the Nat Williamson family, in Guilford County, North Carolina, were far more “worthy” than his doubts about his work led him to believe. As the captions indicated, the Williamsons were the first African-Americans to receive a loan from the FSA.

The day I saw the photos on the Library of Congress website, I found Nat and his family in the 1930 census, living in Washington, North Carolina. He was a 41-year-old farmer, living with Evannar, his 39-year-old wife of 18 years, and their three sons and three daughters. One of those sons was 6-month-old Nathan. In the Internet white pages, I quickly found a listing for a Nathan Williamson in North Carolina, and called. The person who answered said I had the correct Nathan, but that he wasn’t home. She took down my name and phone number and the reason I called.

About a week later, no one had called back, so I did some poking around on the Internet, and was shocked to find that Nathan Williamson had passed away only four days after I had called. So I decided it was prudent to postpone further contact with the family. But two weeks later, I received the following email:

“Let me introduce myself. My name is Vivian (Wade) Sexton. I am one of Nat Williamson’s granddaughters. When I returned to North Carolina for my late uncle’s funeral, his daughter told me someone had called wanting to speak to her father about our family history.”

Vivian proved to be an engaging and valuable resource. She told me that the family has known about the photos for a few years. My interview with her is posted below. She sent me a copy of a newspaper article that appeared around the time that Nat was approved for the FSA loan. The source is unknown, but was probably the Greensboro Daily News. Here is an excerpt from the article, entitled: “Negro Sharecropper Will Get Federal Loan of $2,980 For Purchasing Farm.”

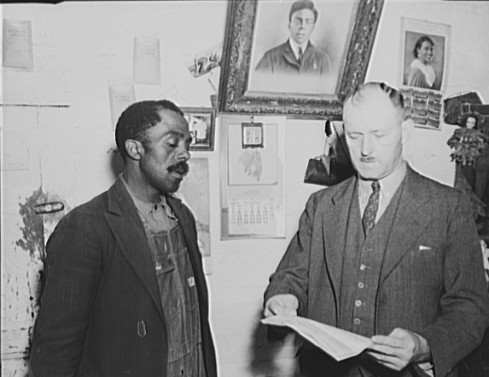

A Guilford County Negro sharecropper will receive what is believed to be the first land purchase loan to a member of his race in the nation. It was announced yesterday by Edgar H. Anderson, of Greensboro, county supervisor of the Farm Security Administration.

The recipient, Nat Williamson, who resides 17 miles east of Greensboro, was notified yesterday that his application for the $2,980 loan had been approved by regional officials and he may proceed with plans to purchase a 97-acre farm costing $2,350 – with the remaining $650 to devote to repairs and the construction of new farm buildings.

Williamson is the second man in this region – which comprises North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia and West Virginia – to receive a loan under the new Bankhead-Jones farm tenant act. The first recipient also was a Guilford County farmer – J. E. Jessup, white tenant residing near Liberty.

The 48-year-old Negro has been following approved farming methods, FSA officials were advised, and looks forward to happier days on land he owns. He has 40 years in which to pay his debt, with interest set a 3 per cent.

According to James Donnell Williamson, Nat’s youngest son, with whom I spoke briefly, the FSA program targeted at least one loan for a black family, Nat applied for it and, “My Dad came out on top.”

Seven years later, Nat paid off his loan in full.

“Back then, life was as sweet as the watermelon I was eating.” -Vivian Sexton

Edited interview with Vivian Sexton (VS), granddaughter of Nat Williamson, conducted by Joe Manning (JM), on February 29, 2008.

JM: How did your family know about the photos?

VS: There was a local newspaper story when my grandfather got the loan, and there were some pictures in there. Years later, my cousin, who was in Washington, DC at the time, did some research at the Library of Congress and found the government photos.

JM: How are you related to Nat Williamson?

VS: He was my grandfather. He was born in Caswell County (North Carolina) on March 3, 1887. My mom, Isabell (Williamson) Wade, was Nat’s daughter. She died in 1998.

JM: What was their life like before they got the loan?

VS: My grandfather was a sharecropper in Guilford County. Times were hard, but he managed to provide for his family. He had purchased another piece of land prior to that, but the sale fell through. So the loan enabled him to buy some land for a farm.

JM: Was he descended from slaves?

VS: His father was born into slavery, in North Carolina. That was right before slavery ended. When they were released, they stayed in Caswell County.

JM: How old are you?

VS: 56.

JM: Were you living near your grandfather when he died in 1967?

VS: Yes, I still saw him every day.

JM: Is there a large clan of Williamsons still living in Guilford County?

VS: Yes, and there are also a lot of them still in Caswell County and Alamance County. My grandfather’s brother stayed in his father’s house.

JM: Is your grandfather’s farm still in the family?

VS: Oh, yes. All the kids own it. My grandfather stated that any of his kids that wanted to build a house, he would give them a piece of the land to do it on.

JM: Which children did that?

VS: The oldest son, Marvin; the youngest daughter, Gwendolyn; and one of Marvin’s daughters. My mom built a house there, but later lost it, so my grandfather bought it back.

JM: How many acres are on the farm?

VS: 96 or 97 acres.

JM: What’s the nearest town to the farm?

VS: It’s in Gibsonville.

JM: What did they farm?

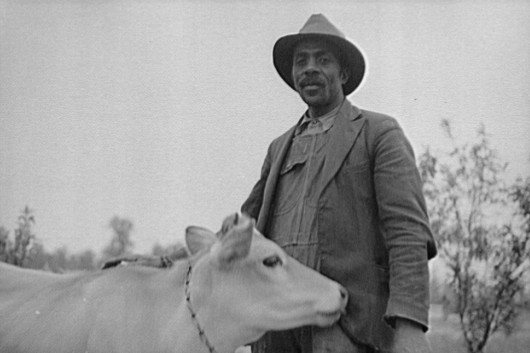

VS: Tobacco and lots of vegetables. When we were growing up, the only thing we bought from the store was like sugar and salt and coffee. Everything else was grown or made. We raised pigs and chickens. My grandfather grew sugarcane and made molasses. We had an apple orchard. He sold butter and eggs, apple cider, vegetables, watermelons and peaches. He had a farm stand in the summer.

JM: Is your grandfather’s farm still operating as a farm?

VS: No. My cousin has a landscape business there. He grows some plants. They all still have gardens in the summer.

JM: Were there a lot of African-American families living in the area back then?

VS: There were a few. Most of them were sharecroppers.

JM: During the time your grandfather operated the farm, and for the next generation as well, did they get along with whites, or were they confined to the black community?

VS: The family that lived next door, the Barbers, was white. My parents sharecropped on that farm. Everyone who lived on that street was like one big family. But you knew your place. When there were no outsiders, everything was normal between us. We were equals. But when an outsider came in, in order to not to put them or us on the spot, we went to the back door instead of the front door. You played the part.

JM: Did you think that your grandfather had a successful farm?

VS: Yes. He worked hard and did a lot of things to make ends meet. He was a carpenter and a mason. He did stone walls. He built the house.

JM: Is it still there?

VS: Yes.

JM: What’s changed about the area since your grandfather was photographed?

VS: It’s still pretty rural. One farm got sold and some houses were built on the land.

JM: What was your grandfather like?

VS: He was great. I was one of the younger grandkids. I followed him around a lot. I went with him to sell the butter and eggs. He’d take me when he went to get peaches. I got to spend a lot of time with him. He was well respected by the black and white community. At that time, whites didn’t call blacks ‘Mister,’ so he was known as Uncle Nat.

JM: Tell me about your grandmother.

VS: She was born Evannar Baynes, in Caswell County. She took care of the home doing the cooking, cleaning, sewing, washing, gardening, taking care of the children, helping on the farm, and being a wonderful Grandma. She spoiled us grandchildren and always had something sweet for us when we went to see her.

JM: How many children did they have?

VS: They had 12, but only six survived till adulthood.

JM: When did you leave the area?

VS: In July 1974, when I went into the Air Force, to make a better life for my son and me. I retired in 1996, and stayed in Florida. When I first went in, I was an aircraft mechanic. They were just starting to have women work on jet planes. Then I hurt my back, so they put me in communications and computers. My first assignment was in the Netherlands. Then I went to Rome, New York. I’ve never been so cold in my life. Then I went to Japan. I got married while I was there. Then I went to Colorado Springs. My daughter was born there. My next base was Panama, in the Panama Canal Zone. My last assignment was MacDill AFB, Florida.

JM: Do you go back often to North Carolina to see your family?

VS: Oh, yes. Every year, we have a big family reunion.

JM: Do they still talk about the FSA pictures?

VS: Yes. Every year, we get out those pictures.

JM: When you were growing up, did anyone ever mention remembering the photos being taken?

VS: No. They didn’t remember. We had the picture of him that was in the paper, but the ones in the Library of Congress we didn’t have. My grandparents never saw those.

JM: So which children are still alive?

VS: Donnell and Gwendolyn. Donnell is about 70. Gwendolyn married Robert Crutchfield. She’s in a nursing home now.

JM: Anything else you want to tell me?

VS: Every year, we used to go back to Caswell County for a family reunion. It was a big thing for everybody in the neighborhood, because everyone was invited. Grandpa had a big truck, and he would throw bales of hay in the back and put a tarp over it and we’d take off, and along the way, we’d stop at all the neighboring houses and pickup whoever wanted to go.

JM: Back when the photos were taken, would all the roads have been dirt?

VS: Yes. The road that my grandfather lived on was a dirt road until just recently. It was originally called Williamson Road, and then it was changed to Bellflower Road. The farm we sharecropped on, owned by the Barbers, the white family, he just passed last year, but his wife, she’s like a mom or a grandma to me. I was the only baby around, so I was like her baby. She’s in a nursing home now, but her mind is sharp as ever. Every time I go back, I visit her, and every Christmas, I send her oranges. And when I was in the Air Force, every time I travelled, I sent her something. The tract of land that my brother and I own is the one with my grandfather’s house on it. My brother lives in the house, and it’s pretty much the way it was back then. There’s a lot of stuff that’s stored upstairs. I’m gonna have to go through it sometime.

Nat Williamson and E.H. Anderson, F.S.A. official. Williamson was the first Negro in the U.S. to receive a loan under the tenant purchase program. Guilford County, North Carolina.

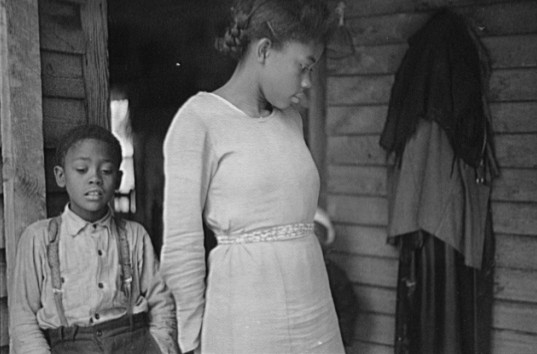

Left to right: (top row) Isabell, Nathan, Gwendolyn; (bottom row) Rebecca, Marvin.

Nat Williamson (1887-1967)

Evannar Williamson (1889-1975)

*Story published in 2008.