Mona Lisa of the Plains

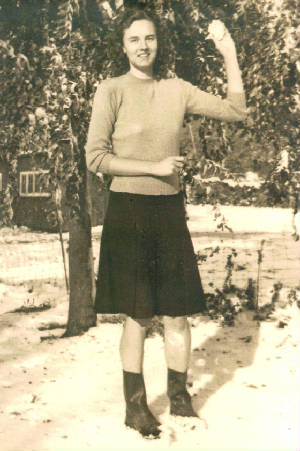

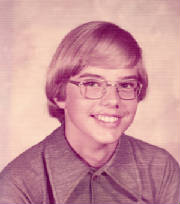

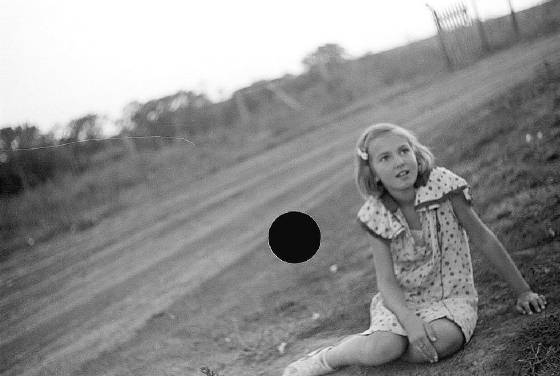

I saw this photograph on the Library of Congress website in early December 2007. I must have stared at it for five minutes. I thought it was one of the most beautiful pictures I had ever seen. I still do. At the time, I didn’t know anything about the photographer, John Vachon, or anything about Seward County, Nebraska. And, of course, I had no idea of the girl’s identity, since she was not named in the caption. I asked myself, “How can I find out?”

I emailed the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division and asked them if they had any records that might help me identify the girl. They quickly replied that they did not, but that I could contact the party responsible for Vachon’s records. So I sent off an email right away, attaching a copy of the photo. To my surprise, I received a prompt reply from Vachon’s daughter, but she told me that her father kept poor records of his work, and seldom kept track of the names of his subjects.

So I did the next best thing I could think of. I contacted the Seward County Independent and talked to Stephanie Croston, the editor. I suggested that she publish the photo and see if anyone recognizes the girl. She was excited about the idea. And so, on the morning of January 9, 2008, the article came out. I caught it on the Web.

“Do you know this girl? Who was she? What became of her?’ That was the first paragraph under the photo. Early that evening, an email popped up on my computer. It said, in part:

“We were very surprised to open our local paper today and find my mother-in-law’s picture on the front page. Claudine is now 79 years old and lives in Seward County. This picture bears a likeness to my daughter, who is almost 8. Claudine would have been about 10 in the photo. She has spent her life in Seward County, most of it on the farm. Like so many people of her era, she is a treasure trove history of what life was like back then on the farm. My husband and I live on the farm she grew up on. My name is Lonna Richters, and my husband is Roger Richters, Claudine’s son.”

I was stunned and excited when I talked to Roger and Lonna an hour later, and so were they. Several days later, I called Claudine and interviewed her for over an hour, her 70-year-old photo staring back at me from the coffee table. It was downright eerie. She was a delight, as were Roger and Lonna, with whom I have had many enjoyable and sometimes emotional conversations. Of course, there was a follow-up article in the Seward County Independent, and then another by Cindy Lange-Kubick, for the Journal Star in Lincoln, the state capital. And I made sure to notify Vachon’s daughter, who was pleased to know that the photo had been identified.

Roger told me that the Seward County Independent also published the photo in 1979, at the request of the Nebraska Historical Society, which was also trying to identify her. Claudine recognized herself right away, but no one ever followed up on it, and the photo, whose historical significance was not fully understood, simply became a treasured curiosity for the family.

As I write this, it’s been about two months since Roger and Lonna first contacted me. Since then, they have sent me dozens of family photos, and most recently, copies of pages of a diary that Claudine kept from 1937 to 1942. Follow the links and see the interviews, the photos, and the diary. You can even listen to about five minutes of audio excerpts of my interview of Claudine. Roger now often refers to his mother as “Mona Lisa of the Plains.”

*All photos and images below provided by Roger and Lonna Richters, unless otherwise noted.

On Wednesday, October 26, 1938, according to John Vachon’s personal letters published in John Vachon’s America, the Farm Security Administration photographer, then 24 years old, drove 60 miles west from Lincoln, Nebraska, to York, Nebraska, probably on what is now called Route 34. He would likely have left early in the morning, because he had an appointment in the afternoon to photograph a meeting of farmers in York. Thirteen of Vachon’s photos taken on that day in York are posted on the Library of Congress website.

On his way, he would have passed through the Seward County town of Utica. About five miles north of town, on a dirt road, Jake and Anges Abele lived on their farm with 10-year-old daughter, Eunice Claudine. We can speculate that Vachon made an impulsive decision to wander some back roads to look for a few interesting shots of farm life. On one of those roads, he saw a young girl, perhaps getting ready to walk to school. He jumped out of his car, toting his Graflex Speed Graphic 35mm camera, and asked her to pose for a picture. He may have asked her parents. No one knows, because the girl, 70 years later, doesn’t remember, and the now-deceased parents never mentioned it.

Eunice Claudine Abele was born August 13, 1928, in Seward County, Nebraska. She was the only child of Jacob and Agnes Abele. Jacob was born in Seward County in 1898, to Gotlieb and Louise Abele. He married Agnes Bohnen in 1921. She was born in Nebraska in 1903, to John and Emma Bohnen. Agnes died in 1963, and Jacob died in 1980.

Known all her life by her middle name (the 1930 census lists her as E. Claudine Abele), Claudine married Gerald in 1948, and had two children, Gary and Roger. Several years later, she took over the farm, and then passed it on to Roger after retiring from farm life.

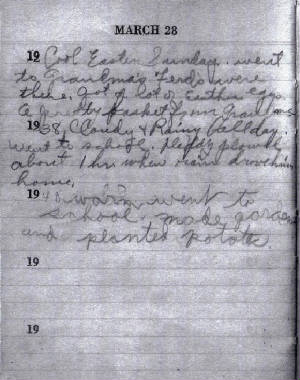

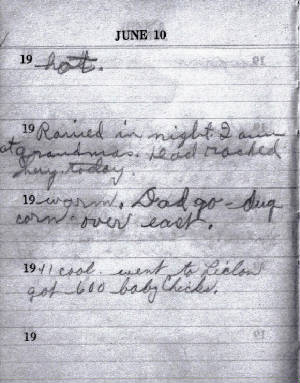

Claudine kept a diary as a child, but there are only several entries for October of 1938. Two days after Vachon took the now iconic photo, she wrote, “Warm. Dad finished hand picking corn today.”

Edited interview with Claudine Abele (CA), conducted by Joe Manning (JM), on January 14, 2008.

JM: What do you think of the picture?

CA: I don’t know. It’s a good picture, isn’t it? Someone said, ‘Oh, you sure looked cute when you were young, but you’re pretty good now.’

JM: Do you remember being photographed?

CA: I don’t remember being photographed, but as I look at it, I think I can remember that dress. My neighbor girl, she was in the eighth grade when I was in the first grade, and I got a lot of her hand-me-down clothes.

JM: At the time of that picture, what do you think your life would have been like?

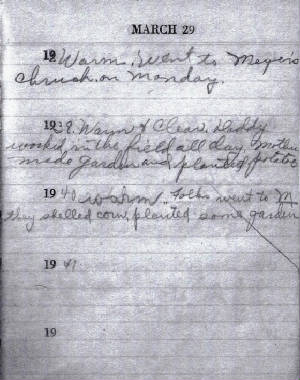

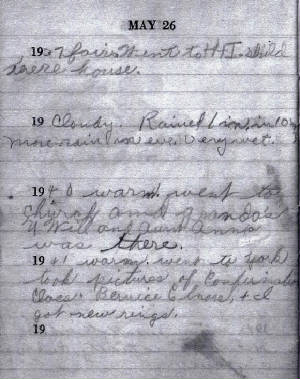

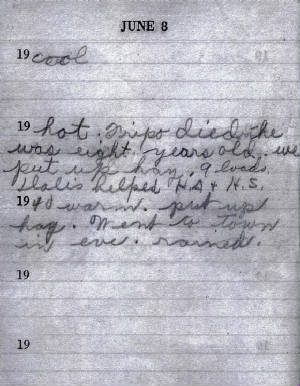

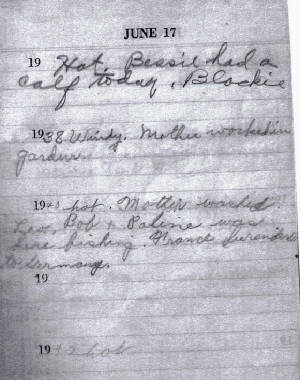

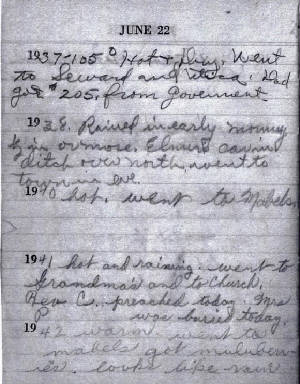

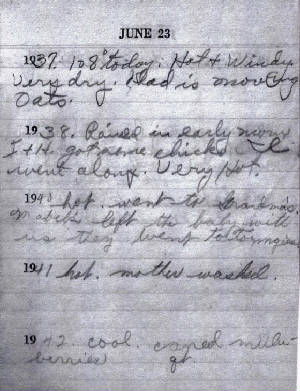

CA: I can’t remember much of it. I went through my diary, and it’s very interesting. A lot of it was written in pencil, and a lot of people were referred to by their initials.

JM: I think most people would think you look thoughtful in that picture, maybe a little sad.

CA: I suppose. I was shy. I was an only child. When I went to school, there were no other kids who were the only child. Maybe it had something to do with that time being the Depression. But my folks had tough times before that. I was born in Seward. My folks lived in town then. They were married seven years when I was born. The first year they were married, they farmed. Her dad had died, and they moved into a small house. Mom worked in a grocery store, and Dad did different things. He was an ice man. He set the tent up for the mortuary. He worked for a nursery, making cuttings to make new trees and bushes. Then they decided to go back out and farm. That was about 1930. Dad owned the 80 where we lived, and Grandma bought an 80 across the road. I remember that it had hailed, and we went out and saw that we had lost the wheat crop. I could see the holes that had been pressed into the ground from the hailstones. We lived on Lincoln Creek. Dad cleared a lot of that land, got rid of the trees, and chopped a lot of wood. People burned a lot of wood in those days, either wood or coal. He sold some of the extra wood. He cut wood all his life. I remember going out there in the evening and he’d burn the stumps and the brush. He used a two-man saw. He was on one end, and Mom was on the other end, at least part of the time. He also had some brothers that helped him.

JM: What kind of work would you have been doing on that farm when you were 10 years old?

CA: Well, I don’t remember now. But I remember some of the other things we did. According to my diary, we had a theater in Utica, and Mom and I would go there. It probably only cost a dime. Then they had free movies once a week out in what was like a park. Someone in town would show them so people would go in and shop, and some would bring in their cream and eggs. In the evening, Dad listened to the radio. He loved boxing. And he subscribed to Successful Farming and Farm Journal. And Mom, she sewed and mended.

JM: What kind of house did you have?

CA: There were six rooms and a closet, but they were very small rooms. I think the house was 28’ x 36’, one floor. Later, Dad dug a cellar underneath it. He had a horse, and he hauled the dirt out of that hole. Then he got some bricks and bricked it up, and made a brick floor. He put some cement steps down to it, and they were pretty steep. Dad built a porch onto the house later so that he could put the cream separator in it. It had been in the corner of their bedroom in the wintertime. In the summer, they’d take it out to the garage. He built a one-car garage. He used it for the washroom. It was right next to the windmill, and he would pump the water, if the windmill wasn’t running, and fill the boiler on top of the wood stove. He’d go out in the morning and heat it up so Mom could wash. She washed about every two weeks. That was the year he got sand and cement and poured sidewalks from the house out to the windmill. It was a real narrow sidewalk; you couldn’t ride a little tricycle on it. And we had a sidewalk to the cave. The toilet was off that way.

JM: Did you have electricity then?

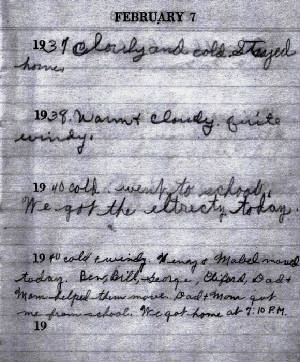

CA: We got it soon after that, in the early ‘40s. It’s in my diary. It says that they were stringing the wires for electricity. And then it says that we bought a Speed Queen washing machine and a refrigerator. But they didn’t have an electric stove till the late ‘40s or early ‘50s.

JM: When did you get indoor plumbing?

CA: Forty-four years ago, when my youngest son was two years old. We got running water at the same time, and then we put in central heat and air conditioning.

JM: Do you remember any tornadoes?

CA: They had a big one in the ‘40s. It took the roof off the amphitheater in Seward, when they were all out there watching the fireworks on the 4th of July. The people had to scamper to their cars. It came down within four miles of us, but then it went in another direction. Our neighbors came over and went into the cave with us. We went to the cave quite a few times. That’s where Dad put all his potatoes. He grew lots of potatoes. In my diary, it says he had two wagon loads one year, the wagon that they put the wheat in to take to town. They were 50-bushel wagons. That cave was on the farm when we moved there.

JM: I understand that you are very tall, about 5′ 10″.

CA: Well, I got my height when I was 12 or 13. Boy, I was a string bean.

JM: You must have been a lot taller than your girlfriends.

CA: I sure was. I sure didn’t wear high heel shoes many times.

JM: When you were growing up, what kind of farm did you have, and what did you grow? Did you also have beef cattle?

CA: They had short-horned cows. They’re a dual purpose cow. They give milk, but not as good as the Holsteins. The short horns were also pretty good beef cows. Mom would always milk more cows than Dad did. She was good at it. Sometimes she’d get back to the house after it got dark, and she wouldn’t leave the kerosene lamps on for fear they could start a fire. I would get scared in the house, so I’d crawl under the kitchen table. I’m still scared of the dark when I’m alone. We lived out of the garden. We canned peas and corn and tomatoes and tomato juice. And we canned beef. Once, Mom canned a whole bunch of mulberries. My aunt lived right next to us, and they had five mulberry trees. We’d put an old sheet down and shake the trees, and you had to sort through them and get the bugs out. Then we’d wash them up and can them. And they were good if you cooked them with red cherries. We get these gallon cans of them. And we’d also can the mulberries with rhubarb. I had a lot of chickens, and my mom did, too. She got 600 chicks, and that would give her almost 300 laying hens. She would butcher some of them to eat. Grocery stores in town had little wire pens in the back, and they had chickens in there to sell. If you had excess fryers, you would take them in there, and people in town would go in and buy one, and dress it themselves.

JM: How old were you when you got married?

CA: I was 19. That was 1948.

JM: How did you meet your husband?

CA: We always had extra tomatoes. I don’t know how they found out that his parents needed some, but they did, and we took tomatoes over to his parents. He was seven or eight years older than I was. So then he started coming over and we would go to the movies. He was a good dancer, but he never taught me how. We just went to the movies. That was our entertainment. That was August or September when I met him, and he gave me a diamond on the first day of next spring. We were married on June 20th. We lived down by McCool (McCool Junction, about 20 miles from Utica). His dad bought a half-section down there, one half for my husband, but he and his dad didn’t get along that well. So after about three years, we came back. My grandmother had another farm, so my folks moved over with her, and we took over the farm. That was about ’51.

JM: When you took over the farm, did you have any children yet?

CA: Yes. I had Gary.

JM: Did you have any farmhands?

CA: No. My dad would help us some. He was still farming. He lived six miles away.

JM: You must have been pretty busy, with a little baby, too.

CA: Yea. And I canned a lot of stuff, I tell you, jars and jars of stuff.

JM: When you were a girl, did you ever dream that you would leave the farm, and go away to do something else?

CA: I don’t really know. I took a correspondence course after high school, and I was a secretary for a while. But I liked to farm.

JM: When you were in school, did you miss parts of school because of the harvest?

CA: No, I didn’t have to help. Mom helped out a lot. She was my dad’s right hand.

JM: Did you ever travel outside of Nebraska when you were growing up?

CA: Yea. Around ’39 or ’40, my aunt and uncle traveled to some sort of seltzer springs in Missouri, for their health, and we rode along with them. My parents didn’t do that sort of stuff, but we rode along anyway. We went to Arkansas and Oklahoma, about five states in a week, I think, and traveled about 1,800 miles.

JM: Was that a great adventure?

CA: Yes, it was. I didn’t do many of them. It’s the only one I did when I was a girl. Then we only went away twice after we were married. My husband won a trip through the Co-op to go out to the Colorado Rockies, so we went out there for a few days. On our honeymoon, we went away for a few days, also in Colorado, but then he had to hurry back to shock wheat for his dad. My husband wouldn’t travel, because he’d been in the Army and seen everything. But I was a homebody, so it all worked out.

JM: Did you ever have any regrets that you didn’t head off to somewhere else?

CA: No. I always got homesick when we left. We always had stuff at home to do. We always had chores: chickens and pigs and cattle and dogs and cats.

JM: When John Vachon took the photo, he was working for the Farm Security Administration. The agency was trying to publicize rural poverty in order to get public support for farm programs, and to document the successful work they were doing. I guess they thought that people looking at your picture might think you were in a terrible situation and needed help. Even now, people looking at the photo might react the same way, and think that you had a dismal future ahead of you. How do you feel about that?

CA: I don’t know. Back then, I don’t think I would have felt that way.

“The other picture on Claudine’s dresser is one of her at age two. The shadow box is filled with things that belonged to her as a young girl. I found them in the attic.” -daughter-in-law Lonna

Excerpts from interviews with Claudine’s son Roger and his wife Lonna, conducted by Joe Manning (JM), on January 10, 2008.

Lonna

JM: You said that you’ve already seen this photo. When did that happen?

Lonna: In 1979, the Seward County newspaper ran the photo and asked ‘Where is this girl?’ At that time, Claudine’s father was still alive, and he sees that picture and says, ‘Claudine, your picture is in the paper.’ And she looked at it, saw the ring on the girl’s finger, and said, ‘I’ve always worn a ring on my right hand middle finger. That is me.’ She was amazed. We’ve always loved this photograph because of the starkness, the 1930s dry, dead grass, the harshness of the landscape, which kind of represents her life, which was tough. Her life is probably easier and more joyful now than it ever was. But all along, she has been a cheerful, happy, positive person.

JM: What was tough about her life?

Lonna: This farm has been in her family for over 100 years. Her dad came and bought the farm in the late ‘20s, when everything was going to heck in a hand basket. And they held it together and worked so hard. The reason they were able to survive in the ‘30s was because when her dad bought this farm, which is down in the river bottom, he planted alfalfa, which has roots that go way down, and they can tap down into the ground water. She didn’t have a house with running water until the 1960s. Her mother died when my husband was just a little over a year old. That was tough for her, because she was an only child. She held this farm together all these years and passed it on to my husband, and we’re still here, and we’re still doing well today because of her. We’re in a position that so few people are, owning all our land, and hopefully, we will pass it on to our son, and that means so much to both of us.

Roger

JM: How did your mother react when she saw her picture in the paper? And what’s happened since?

Roger: She said she ‘bout fell off her chair when she opened the newspaper. She called me and said, ‘You won’t believe it. I’m on the front page of the Seward Independent.’ This is wonderful for my mom, because she’s worked hard, she’s been humble, and she’s finally due for a little recognition. Ever since we saw that photo the first time, we’ve been struck by the beauty of it. It’s compelling. Her eyes draw you in, similar to the Mona Lisa. You want to know what’s on this child’s mind. In fact, I’ve started referring to it as ‘Mona Lisa of the Plains.’ Looking at the picture now, I can see her quiet strength. You know she’s gonna be there, she’s gonna withstand the blows of life. Taylor, my daughter, has the same look. That’s just how she looks when she’s thinking hard about something.

JM: What does your daughter think of the photo?

Roger: She thinks a lot about it. She took a copy to school today. We have several relatives in the area who are teachers, and they’re probably talking about this in their classrooms.

JM: Many people who look at this photo might react by saying, ‘What a bad situation to be in. She must have been a sad little girl.’ After all, the Farm Security Administration wanted to elicit that response in order to gain support for their programs.

Roger: I think the message of that photo is perseverance. You have to believe that times will get better, that the rains will come back. They learned to get through that, and in doing so, it made them stronger and better people. My grandpa always saved money. During the Depression, he would not even buy things he needed. He never even put running water or central heat in his house. In those times, you did everything. You raised the livestock, you butchered it, and you had to drag in water from outside and heat it on a stove. Nobody had any money in their pocket. No one had crops, and they had grasshoppers.

I’ve read stories about how they covered their gardens with blankets, and the grasshoppers would eat the blankets. Mom used to have to walk to school, and she had to walk up this big, steep clay hill. By the time she got up there in late winter when it was thawing, she had about 10 pounds of mud on each boot. Mom lived in Utica with her grandmother the last few years in high school, because the roads were so muddy. To drive back and forth from the farm was quite a big deal because you could slide off the road. She helped out her grandmother. She did her bookkeeping and taxes, and brought in wood for her stove. Mom always talked about the creek being the center of social life before radio. The kids would ice skate down here. They would go out and spear fish by breaking a hole in the ice and tap on the ice farther down, and all the fish would swim toward the other kids by the hole. They hunted and trapped and fished, and most of their activities were down along the creek. There wasn’t a whole lot else to do.

JM: How old was your mother was she stopped working the farm?

Roger: My parents moved to Utica in 1988, so she would have been about 60. Dad would still come out and help me with the farm. He died in 2003.

JM: How much land do you have?

Roger: I have 520 tillable acres.

JM: What do you primarily grow now?

Roger: Soybeans and corn. When I was eight years old, my mom put four bunny rabbits on the edge of my bed on Easter morning, and I grew that into 212 head of rabbits. I sold about 200 head in about three months time. From there it grew into hogs, and in a few years, I was up to 200 head of hogs during the summer months when I was out of school. I ground all the feed for the hogs, filled the feeders, and watered them. Later on, when I got close to finishing school, I had 135 head of cattle and 200 head of hogs, year ‘round. When Dad got older and wanted to retire, I told him that I couldn’t handle all this cattle and hog business, so I decided to focus on grain farming. I credit my success as a farmer to my grandpa and my mother. They always saved. I’ve learned to pay cash, not buy on credit. I’ve been able to grow the farm little by little over the years. Right now, I feel that the small family farm is under attack, and it’s sad to see this culture go. There’s no words to describe what a wonderful feeling it is to farm on your own. It’s wonderful that the family shares in the work. It’s an experience of faith and honor and great integrity.

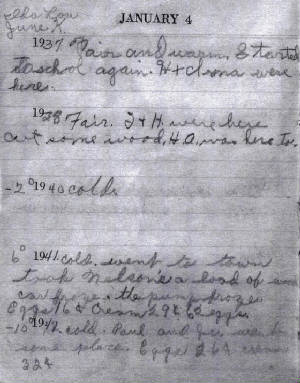

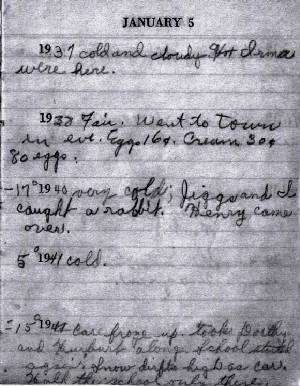

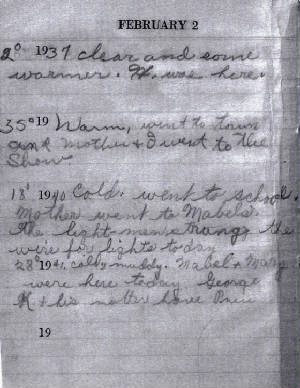

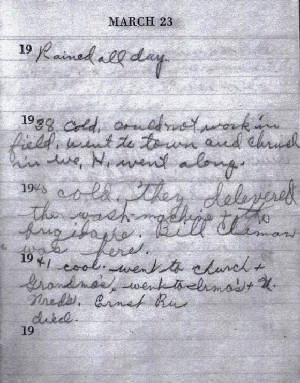

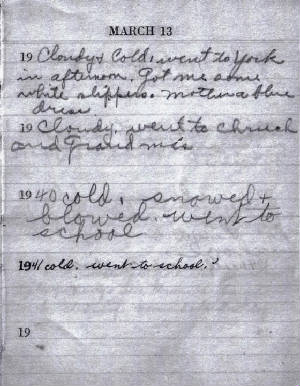

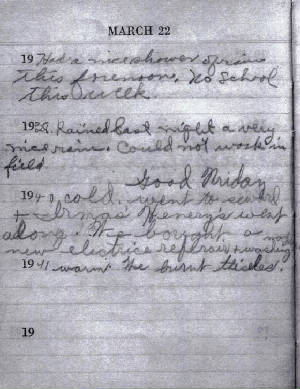

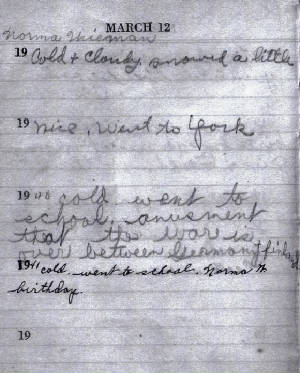

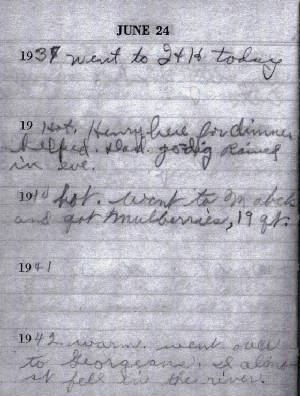

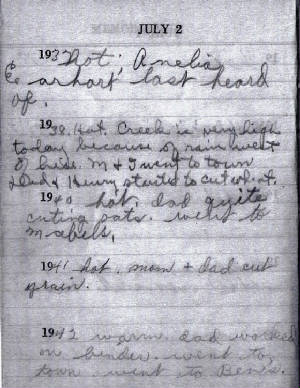

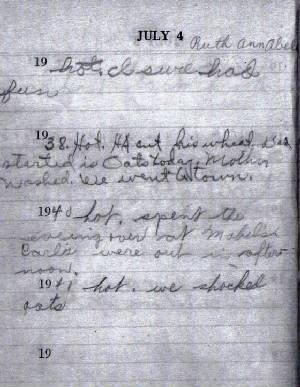

Welcome to Claudine’s childhood diary. Following are 20 pages, scanned from the original diary. This is a so-called “five year diary,” which is designed to allow the person to write down entries for one date for five years on the same page. So on the first page, the entries for January 4, 1937 appear on the first line, entries for January 4, 1938 appear on the second line, and so on. Claudine did not make any entries for 1939, but returned to the diary in 1940. Some pages do not have entries for all five years.

There are no startling revelations here, just the simple words of a very thoughtful and observant girl who, despite her family’s day-to-day struggles, obviously treasured the little things that enriched her life on the farm during the Great Depression and the early days of World War II.

Listen to a five-minute excerpt from my interview with Claudine

Thanks to Claudine, her son Roger, and his wife Lonna for being so kind and helpful, and for standing tall against the odds, helping to preserve the great tradition of the family farm.

*Story published in 2008.

Web Links

Library of Congress information about John Vachon

Smithsonian interview with John Vachon

Books

John Vachon’s America, edited by Miles Orvell, University of California Press

Dust Bowl Descent, by Bill Ganzel, University of Nebraska Press