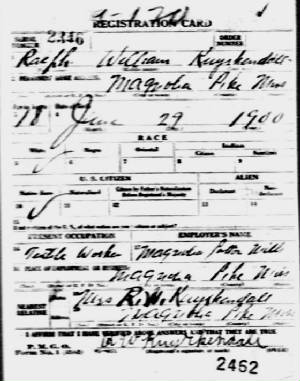

Lewis Hine caption: Ralph Kuyrkendall. “I’m learnin’ to spin in Magnolia Cotton Mill. Work with Blanch —. I’m 10 years old. Been in the First Grade three years and Second Grade one year.” Location: Magnolia, Mississippi, May 1911.

“I don’t think my grandfather ever completed elementary school. It is likely that he quit completely because of his father’s early death.” -Karen Walsh

**************************

“From April 29 to May 16, 1911, I made quiet visits to every cotton mill in the state, with but one or two exceptions, and in all cases, spending some time inside the mills at noon-hours, as well as other hours spent around the mills at noon-hours, and around the homes at various times. In some of the villages, I made a careful house-to-house canvass, locating the homes of the working children and getting data about them.” -Lewis Hine, from Child Labor in the Cotton Mills of Mississippi, archived at the Library of Congress

According to Child Labor in the American South, by Joshua Kuderna (University of Maryland, Baltimore County), the Magnolia Cotton Mill opened in Magnolia, Mississippi in 1903. According to a number of investigative reports by the National Child Labor Committee, Mississippi had the lowest standard of wages for children and adults in 1908 among cotton mills in the country. Federal investigators reported that the smaller villages were often primitive, their streets just wagon roads, and chickens, pigs and cows ran free.

In 1908, Mississippi became the final state in the South to pass a child labor law. The law called for no children under 12 to be employed in cotton or woolen mills. The laws also called for no more than 10 hours a day for children under 16. But in 1911, the National Child Labor Committee found that workers at the Magnolia Cotton Mill were working 63 hours a week.

In a number of photos by Lewis Hine at the Magnolia mill, it was apparent that many of the children were under the age of 12. In fact, he reported that the children he encountered were told to say they were 12 years old, even if it was obvious that they were younger.

In February of 2007, my Lewis Hine Project was the subject of a story on National Public Radio’s news program called “All Things Considered.” Shortly after, I received the following email:

“I heard about your project by total chance on NPR, so I looked it up through their website. I don’t know if you are soliciting people to come forward. I know there are many stories that were never told. Our family is connected to the photos through my grandfather, Ralph Kuyrkendall, from Magnolia, Mississippi. Many of the family members were also photographed in front of their mill house. If you wish to have any other info, please email back. -Sincerely, Karen Walsh.”

I found the photos of the Kuyrkendall family on the Library of Congress website right away and replied to Ms. Walsh, telling her I was interested. I had already spent countless hours of research on many other photos, trying to track down descendants; so being contacted first by a descendant of a child laborer was a welcome surprise.

Ralph Kuyrkendall was born in Mississippi on June 29, 1900, according to his WWI draft registration. His parents were Jesse Morgan Orval Kuyrkendall, a Kentucky native; and Emma Joanne Allen Kuyrkendall, a Mississippi native. They were married about 1893. Ralph married Velma Ray about 1917. He was about 16, and she was about 19. They had four children.

My caption: According to Karen Walsh, these are the identities and approximate ages of the persons in the photo: Front row (L-R): Ralph (10), Inez (13), and Hazel (14). Back row (L-R): Roy (9), mother Emma (43), Emma (2), Dudley (6), father Jesse (61), and Mildred (1). Missing from picture are sons Jesse (17) and Ray (15). Father Jesse died of consumption (tuberculosis) just six months after this photo was taken.

My caption: According to Karen Walsh, these are the identities and approximate ages of the persons in the photo: Front row (L-R): Ralph (10), Inez (13), and Hazel (14). Back row (L-R): Roy (9), mother Emma (43), Emma (2), Dudley (6), father Jesse (61), and Mildred (1). Missing from picture are sons Jesse (17) and Ray (15). Father Jesse died of consumption (tuberculosis) just six months after this photo was taken.

Lewis Hine caption: Kuyrkendall family, recently from farm. Three children in front row (one ten and one twelve) and one boy not here, work in Magnolia Cotton Mills, Magnolia, Miss. Location: Magnolia, Mississippi, May 1911.

Edited interview with Karen Walsh (KW), granddaughter of Ralph Kuyrkendall. Conducted by Joe Manning (JM), on April 16, 2007. Transcribed by Jessica Sleevi and edited by Manning.

JM: How did you first see this picture?

KW: I had started doing genealogy research on the Internet, and for the first time, I Googled my grandfather’s name, and it came up many more times than I imagined that it would. I just started clicking on different things, and one of the last ones was the Lewis Hine photo. Actually, it didn’t show the photo, it just had the title. It was listed as being at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County Library. So I emailed the research librarian and said, ‘I think this might be my grandfather. Is there any way that I can see this photo somewhere?’ And he emailed back and said, ‘I can get it copied and emailed to you.’ And when he did, he sent me two photos. I was really excited.

JM: Had you ever seen a picture of your grandfather as a boy?

KW: No, never.

JM: Did you know that your grandfather came from Mississippi and worked at a cotton mill when he was a child?

KW: Yes. I knew that area because that’s where we would go on summer vacation. My dad would take us there because that’s where both of my parents were from. My mom was from McComb, and my dad was from Magnolia. I knew my grandfather. He died in 1995. I think he was 95 years old. I think the last time I saw him was about 1989.

JM: Did you grow up in Mississippi?

KW: No, I was born in Florida, in 1958. My dad, Bruce, was born in Mississippi, in 1919. He had to quit school in the eighth grade. What he made was added to what his father (Ralph) made for a family with four children. Dad joined the Navy about 1939, and continued to contribute to the finances of his parents and siblings. He settled in Florida when his naval career was over. He died in 2002. My mother, Mary, is still living. She’s 88. She was born Mary Boyd, also in Mississippi.

JM: What did your father do for a living after he got out of the navy?

KW: For a little while he tried different things, like running a car lot with a friend. He was very good with his hands, very mechanical, and he finally worked on the air conditioning and heating system for a company called Independent Life.

JM: What did your grandfather do for a living?

KW: He worked at the cotton mill; then he was a carpenter. He also had a plum orchard. When he got older, he had a little shop where he sharpened saws and fixed tools.

JM: When he worked as a carpenter, did he work for himself?

KW: No. He worked on construction jobs. I remember hearing that once he fell from a two-story building. I’m sure he was laid up for a little while. Amazingly, he did not get seriously hurt.

JM: What was your grandfather like?

KW: I can’t really say. I just knew him from those summers. When we would go there, I usually would go with my dad, while my mom would go visit her family. I don’t remember that he told me a lot of stories. He would joke about his last name. He said that there were a lot of people in Mississippi with the Kuyrkendall name, but many without the “r.” He would say, “The people without the ‘r,’ were the ones that were caught stealing chickens, so they had to drop the ‘r’ from their name.”

JM: How far back does your family go in Mississippi?

KW: I think it would be Jesse, my grandfather’s father. I haven’t traced where he came from, but he came to Mississippi in the 1880s. He got married not too long after.

JM: How did you know that your grandfather worked in the cotton mill?

KW: My dad talked about it, because he had worked in the same cotton mill. I don’t think my grandfather ever completed elementary school. It is likely that he quit completely because of his father’s early death.

JM: I think the picture of the whole family is wonderful. I’d love to know what their lives were like at that time.

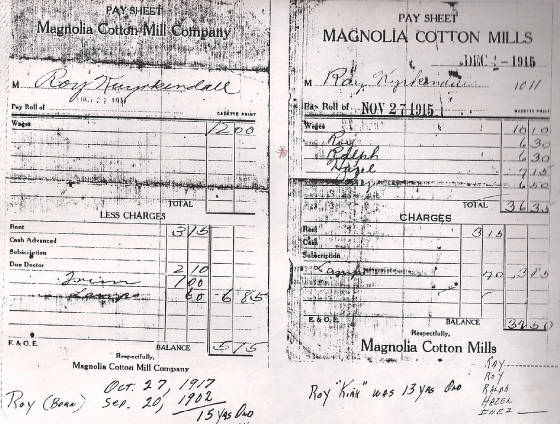

KW: I believe the house in the picture was a mill house. It’s strange, but his father died of consumption that year, in November, six months after the picture was taken. His wife didn’t die until about 1959, at about 90 years old. She had to raise all those children. There were nine children to feed. I think she had four or five siblings that lived in the area. I think they helped her out a little bit, but she also did sewing and things like that. And I guess with her sons working, they pulled through, and she never let those kids go anywhere else. I don’t think the boys ever went back to school, so I’m sure they all worked. We’ve seen some of the receipts that they kept. They had a company store. Their pay was laughable. They were never quite out of debt, and they could barely pay for everything.

JM: It’s interesting that the family photograph is different from most of the Hine photographs I’ve seen. It looks more like a family portrait. It doesn’t look like a spontaneous thing. The older girl sitting in front looks very much like she’s aware that’s she’s being photographed. They seem to have a sense of self-importance, as if they were pleased to be photographed. It looks like they got themselves all spruced up and wanted to look really good.

KW: I think the girls were dressed in their best clothes.

JM: You’re a teacher. How do you feel about your grandfather having worked in this situation?

KW: Well, you know, it was the time. I can’t imagine how hard the times must have been. I try to talk to my students about these kinds of things, and they just don’t have a concept. Back then, they were just doing what had to be done. It’s sad. I look back and wish I could just reach back and change it. But Ralph had a happy life, and he was surrounded by his family.

Ralph William Kuyrkendall passed away on February 10, 1995, at the age of 95.

*Story published in 2009.