Despite eleven #1 singles in the 1980s, and three critically acclaimed albums in the 1990s, Rosanne Cash didn’t think of herself as a singer. From the age of nine, she just wanted to be a writer. Afraid of the downside of fame that she saw her father Johnny Cash experience, she toured infrequently, preferring the quiet anonymity of raising a family, and the solitary life of creative exploration.

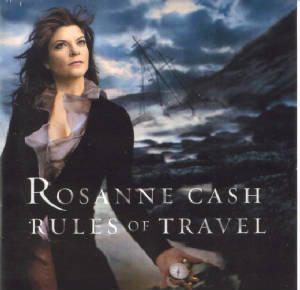

In 1998, with a baby on the way, and a new studio album long overdue, she and producer John Leventhal gathered together some songs she had written and started working on what would become Rules of Travel, a just-released CD that is already being touted by some critics as the best album of the year.

But that first trip into the studio some four years ago was the beginning of a long nightmare that could have signaled the end of her career. She lost her voice ― completely. A specialist found a large polyp on her vocal chords and said it was related to the hormones of the pregnancy. As the baby grew inside, so did the polyp. Rosanne described her reaction in a phone conversation we had in April.

“I found my self-esteem crashing around me when I lost my voice. I went, ‘Whoa, what’s this about? I thought all my self-esteem was around being a writer.’ I went back to bottom, you know, stripping away every single role. I was kind of left with just being myself and being a mom. That’s actually a very healthy thing to go through when you’re approaching middle age, stripping back to basics again. But being a mom was one role I couldn’t strip away.”

So she went about the business of raising her new son, while tentatively putting faith in her voice specialist’s predictions that the polyp would disappear. And when it finally did, she faced the tedious process of getting her voice back in shape.

After graduating from high school, Cash joined her father on tour as a backup singer because she wanted to be with him, not because she had a strong desire to be a performer. When she met Texas-born songwriter and producer Rodney Crowell, and later married him in 1979, he pushed her into recording Right or Wrong, her debut album. The first single, “Seven-Year Ache,” was a sensation, even crossing over from the country charts to the pop charts.

But successive hit albums did not endear her to the Nashville scene. Like her father, she was a rebel who shunned the glossy image of a country songbird. Cash’s marriage to Crowell eventually grew stormy, and in the midst of it all, she broke away and mostly self-produced the beautiful and brooding Interiors, which seemed to chronicle an exit not only from her marriage, but also from Nashville. In 1991, she moved to New York. I asked her if that decision to settle in Manhattan was an artistic statement.

“If an artistic statement is part of the bigger picture, well, I wanted to change my life, yea. It has turned out to be artistically important to me, and it’s been incredibly positive to be plugged into a network of creative people who are working at the top of their game. This city is so profusely alive, and there’s so much culture available to me. I also needed to thicken my skin a little bit, to not be so darkly introspective all the time. New York has helped me with that, along with my husband.”

That second husband is Leventhal, a brilliant guitarist and songwriter who won a Grammy for producing and co-writing Shawn Colvin’s hit “Sunny Came Home.” He and Cash have collaborated on her last three albums, starting with The Wheel in 1993, 10 Song Demo in 1996, and now Rules of Travel.

Despite glowing reviews from Rolling Stone and many other music-industry publications, Interiors, The Wheel and 10 Song Demo sold poorly and failed to receive strong promotion from the record company. Consequently, only her devoted fans avoided wondering, “Whatever happened to Rosanne Cash?” I asked her if that was difficult to deal with.

“That’s very interesting, because that assumes that everybody wants to be the biggest superstar that they can possibly be. I don’t have that desire. I don’t want to make the sacrifices required to be a household name. And if I started feeling bad about people not understanding my work, or that I’m just seen as Johnny Cash’s daughter, I could waste all my energy trying to prove something. I try to appreciate the people who do get my work.”

With Rules of Travel, both Cash and her record company (Capitol) are geared up for a full-fledged promotion of the album. Her extended tour takes her to such places as England, Quebec, California and Texas; but not before her stop in North Adams. I posed the obvious question: “Does this mean you’re no longer afraid of fame?”

“I’m less afraid of it destroying me. I still have some ambivalence about it, because I don’t like being in the public eye that much. I’m a pretty private person. Writers are generally solitary people. It kind of goes against my nature to perform and promote and all the other stuff. But at the same time, I didn’t make this record just to play in my living room for my friends.”

Her sharp and insightful songs certainly deserve to be enjoyed well beyond her living room. Cash has a special talent for composing very tight and concise melodies. She makes great use of minor chords, and creates effective bridges that make their statement and disappear quickly. I asked her if this comes naturally to her.

“I do work hard at it. At the same time, that Beatles song structure is always floating somewhere in the back of my mind. I immersed myself in that all through my youth, so it’s in there, no matter what I do. Sure, there’s a natural flow to things, but at the same time, there is a lot of editing and refinement. And, you know, I happen to like minor chords.”

“It helped to be around writers like Rodney and Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt. None of them write about themes. They write about the specifics. Great songwriters don’t write about metaphors, then kind of assume the specifics. They write about the specifics, and then people write their own metaphors into it.”

In her lyrics, Cash does not shy away from provocative subjects. In “This World” (Interiors), she laments about child abuse (“I read about this baby/She got beat up by her dad/She was nine months old/And he was a full grown man.”). In the sarcastic “Take My Body” (10 Song Demo), she expresses anger over the way the media treats women like sex objects.

Perhaps no lyric by Cash is as poignant and poetic as the chorus to “Child of Steel,” which is an attempt to lift her adolescent daughter’s self-esteem.

“The soul takes its blows, and it does not reveal/The heart opens slow, and it takes time to heal/You can let go, it’ll all turn to gold/My sweet child of steel.”

“I was singing that song live at this benefit in Aspen,” Cash recalls, “and Ringo Starr was in the audience. He came up to me after the show and said, ‘You made me cry with that song. I feel that way about my own kids. Sometimes they’re so awful and you can’t stand them, but there’s that child underneath.’”

“For me, songs have to start with an emotional inspiration. In “This World,” I read this story in the Daily News, and I couldn’t shake it. I was crying and walking around and wondering what to do. You say a prayer for the baby’s life. Then you turn it into what you know how to do creatively, and offer it up. When you’re a writer, you want to do something that has quality and substance.”

Included in that substance are apparent references to her personal life, an inference she does not appreciate.

“I don’t like the idea of confessional songwriting, or people applying that to me, because it’s not a diary. That implies that there is no art or craft to writing songs. There’s a tremendous discipline to songwriting. Of course, I draw from my own life. Every writer does. You can’t just get it from television and movies. But at the same time, I use poetic license wherever I want.”

Like those of Joni Mitchell and Billie Holiday, Cash’s voice is so emotionally powerful, and yet so direct and understated, that listeners can’t help feel that they are overhearing a whispered secret.

After a long drought and a rejuvenated voice, Cash says she’s being treated like a new artist, a characterization to which she subscribes. “I always feel like I’m starting over again, with every record, and with every song I write.”

A trio of Rosanne Cash’s essential recordings

Interiors (1990)

Following a series of highly entertaining country-rock albums, Interiors is a shocking change of pace. Dark and introspective, the melancholy melodies, thoughtful lyrics and intimate presentation tug at the heart. Despite its relative brevity (34 minutes), its emotional weight is almost too much to bear in one sitting. Best line (from “Dance with the Tiger”): “Creatures of habit, American fools/Reaching for stars while we’re standing on stools.” Best song: “Paralyzed.”

10 Song Demo (1996)

This is a collection of demos that Cash and Leventhal produced in their home studio. Capitol Records decided to release them on a CD without fanfare. Each song is a little masterpiece. Spare and stark, they haunt like old black and white photographs. This is Cash’s most artful work.

Best line (from “List of Burdens”): “Don’t put my love on your list of burdens/When I’m bringin’ it home to you.” Best song: “The Summer I Read Collette.”

Rules of Travel (2003)

A remarkable comeback album, this is her most pop-oriented recording since the Nashville-produced Rhythm and Romance. The Beatlesque arrangements and hooky choruses are irresistible; but once again, it’s the songs and Cash’s intimate vocals that shine through. Best line (from “Will You Remember Me”): “Will you remember me like the circled stones/On the ancient hills where you walk alone.” Best song: “September When it Comes,” a touching duet with father Johnny Cash that may become her most remembered creation.