Lewis Hine caption: 2 violations. Simon Birdsong (left hand boy) said: “I’m about 12.” His mother said: “He’s old enough to work all right,” but the boy admitted that she had to sign up that he was older than he was. He appears to be 10. Has had job doffing for several weeks. Could not write his own name. Has had no schooling after the 1st grade. Wylie Haw (right hand boy). Mother says he is 12 years old now. Been working 1 year. She is a widow. Location: Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina, November 1914.

People often ask me how I select which photos to research. Well, there are a lot of factors, but a unique name is a big help, and you can’t miss with Simon Birdsong. I saw this photo one morning and found Simon in the Social Security Death Index immediately. He died in Roanoke Rapids in 1993. I emailed the local library and requested his obituary, and two hours later, they emailed it back. He was survived by one child, a daughter named Jean Tomes, of Roanoke Rapids. I found her phone number and called her. She was stunned. I emailed her the photo. The next day, Ms. Tomes replied:

“You won’t believe how much excitement your telephone call has generated within the Birdsong family. Phone calls and emails have been going back and forth like crazy.”

I was able to determine that Simon was working at the Rosemary Manufacturing Company, the first significant textile mill in Roanoke Rapids. According to Halifax County: economic and social: a laboratory study in the Rural Social Science Department of the University of North Carolina, by Sidney B. Allen (1920):

“The Rosemary Manufacturing Company operates the largest cotton damask mill in the world. From their 45,000 spindles and 1,200 looms there comes more than a third of the product which adorns the tables of America’s dining rooms. Millions of yards of table cloth, and hundreds of thousands of dozens of napkins and pattern cloths are produced yearly.”

“The Rosemary Manufacturing Company began to operate in 1901 with 3,000 spindles and 50 looms, making only one grade of goods, of medium quality. The plant has steadily grown in size, and the quality of the product has steadily improved. Today the plant manufactures fifty styles of damask.”

“The plant has a modern and completely-equipped machine shop, a supply house, two steam electric turbine power plants, and two large warehouses for the storage of thousands of bales of cotton. The machine shop is the largest in this section of the state. It employs more than 25 skilled mechanics, and the shop equipment is valued at more than $15,000. It is one of the best-equipped cotton mill machine shops in the South. The plant operates entirely from its own power, generated by its two turbine power plants.”

“Between 1,000 and 1,100 operatives are employed in the mills of this company, and their condition speaks highly for the unselfish interest that the company takes in its employees.”

“In the village, which is owned by the company, there are nearly 300 single, and about 90 double, houses. They are well-ventilated and modernly equipped. They are rented to operatives at a very low rate.”

Despite this favorable description of the mill, when Simon was photographed, probably in front of his mill village house, he had just turned 11 years old a month earlier, well below the child labor law minimum of 14, and that’s what mattered to Hine.

According to census records and family genealogy reports, Simon Louis Birdsong was born in Gumberry, North Carolina, on Oct 1, 1903, the son of Charlie Emmett Birdsong and Lelia Jane Cooke. In 1910, the family was living in Seabord, NC, where the father was a farmer. He died two years later, and in 1920, Simon lived with his mother in Roanoke Rapids. Both of them worked in the cotton mill. He married Martha Loraine Bridger on June 25, 1930. At that time, they were living in Hopewell, Virginia.

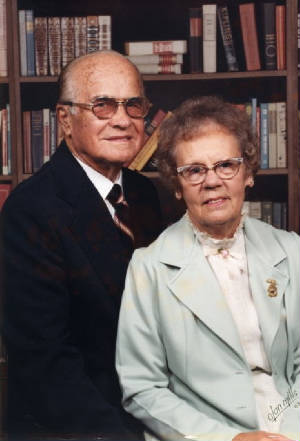

Simon passed away on April 25, 1993, and wife Loraine passed away on September 29, 1996, both of them in Roanoke Rapids. Their daughter Jean tells us more.

The following are excepts from my interview, conducted mostly via email, with Jean Tomes, Simon’s daughter.

“My father, Simon Birdsong, descended from John Birdsong, who came from England to Virginia in the early 1700s. John had 4 wives and 15 children. Daddy descended from the youngest child, by the 4th wife, Charles Hancock Birdsong and wife Sally Edwards Birdsong. All these children were well endowed by their father or married into families of good standing and wealth. John Birdsong owned several thousand acres of land in Sussex Co., Virginia.”

“Simon’s father, Charles Emmett, died in 1912 at the age of 40 years. With three siblings, my father didn’t have much choice but to go to work at the cotton mill, if there was to be food on the table.”

“Mr. Hine reported that Daddy had not gone past the first grade, but the mill hired a teacher to work with all the young children after they got off work each day. As soon as their evening meal was finished they would all go to the Halifax Farmers store on the ‘Avenue’ and have school on the second floor. One of Daddy’s classmates (and work mates) was Julian Allsbrook, who became an attorney and was a state senator in North Carolina for many years. Ironically, my late husband, Homer, and I bought the Allsbrook house in 1984, and restored it to its original beauty, as when it was built in 1912 by the president of the paper mill.”

“My mother, Loraine Bridger, was a direct descendant of Gen. Joseph Bridger, who came to Virginia from England in 1650. He was a member of the House of Burgesses and was the councilor to the King of England until he died in 1686. My mother was born on a farm that was an original patent to Gen. Bridger. Her father was a schoolteacher, tax collector and farmer. When he died suddenly, I don’t think my grandmother knew how to handle the finances and very shortly, near the Depression, she lost the farm. She and my mother moved from Isle of Wight County, Virginia, to Hopewell, Virginia, where my father Simon had gone to work in the silk mill, along with a friend from Roanoke Rapids, NC.”

“My father, whose nickname was Bird, was an excellent drummer. He played with the original Kay Keyser band (Kyser grew up in Rocky Mt., NC). Daddy took his drums wherever he went and had no problem getting jobs playing for dances.”

“When my mother met Daddy at a dance, where he was playing the drums in Hopewell, she said she thought he was the most arrogant person she had ever met, but she loved his beautiful, thick, curly, black hair. They were married secretly in June 1930, and I arrived on the scene in May of 1931.”

“My father had a job working at a bakery, and he owned a car. Several of his friends told him that DuPont was building a new plant in Waynesboro, Virginia, and they would pay for the gas if Daddy would drive them to Waynesboro. It was at least a five hour drive in 1933.”

“When they arrived at the DuPont employment office, all the men got in line to talk to the personnel manager. Since Daddy already had a job, he just walked over and sat by her desk. As each hopeful applicant reached her desk she would ask, ‘What type work have you been doing?’ If they said carpenter, plumber, etc., she would say, ‘Sorry, we are only looking for sheet metal workers.’ After listening for a while, Daddy got in line. When he reached her desk and she asked him what type work he did, he answered, ‘I am a sheet metal worker.’ Daddy was the only man who got a job.”

“My grandmother and Mother and Daddy piled everything they owned into the car. I cannot remember what type car they had, but it was probably not a Ford. Daddy did not particularly like Fords. They moved to Waynesboro and started a brand new life.”

“After several weeks, Mr.Nemo, the supervisor in the Sheet Metal Department said to Daddy, ‘Bird, do you know anything at all about sheet metal?’ Daddy replied, ‘Not a damn thing!’ Mr. Nemo told Daddy that since he had been so honest, he could stay and they would teach him. That was probably one of the best decisions Mr. Nemo ever made. My father became one of the best sheet metal workers that ever worked at DuPont. He was born with more common sense than any person I have ever seen. Had he been fortunate enough to have had a formal education there is no doubt in my mind that he would have been one of the finest engineers who ever lived.”

“My mother, who had attended college, worked for hours with my father on his reading and writing. Many times Daddy was offered promotions at work, but declined as he felt his lack of reading skills could cause problems.”

“A number of DuPont employees formed a dance band with Daddy as the drummer. Later Daddy formed his own band and they played for every university, college, high school and country club in the western part of Virginia.”

“My father bought a new car every other year. The Pontiac dealer in Waynesboro had a waiting list of folks who wanted to buy Daddy’s car when he purchased a new one. When I was growing up, if I ever got a black mark on the white sidewalls, I knew I needed to get the sidewalls cleaned before I got home or I wouldn’t get the car again anytime soon. His cars were immaculate.”

“I am certain my father missed attending school with all the other children and doing all the things that young people did. However, his work experience was probably helpful to him, as it made him appreciate all he had worked for.”

“Daddy was truly one of a kind. No one was a stranger to him for very long. He could enter a campground with their motor home, and within a couple hours know every camper there by name, and they all loved him.”

“Daddy may not have had much money, but he was an excellent dresser. He probably had more clothes than any man I ever knew and everything, shoes, socks, shirts, ties, had to match perfectly.”

“After my father had been at DuPont five years (in the meantime, Mother had started working there also), they built a new home. In 1946, as soon as the Second World War was over, they built another new home, one of the nicest in town.”

“When I was a child, my parents always took me out of school for two weeks or more so they could take a trip to Florida. They continued their trips to Florida until they retired. After they bought a motor home, they traveled all over the United States. The only state they missed was Hawaii.”

“Since I didn’t have a brother, I learned how to do all the things that boys learn with their father. Daddy always wanted me with him when he was working around the house. As a result, I am so very fortunate that I can repair a leaky faucet, repair broken lamps, etc. and do so many things that some of my lady friends would never dare to attempt.”

“When my mother’s nephew, Paul King, was just a young fellow, his father left home, so my parents raised him as their own. They sent him to school and college. Paul had red hair, and I loved his answer when folks asked where he got that red hair. He would say ‘it came with the head.’ Mother and Daddy always took Paul and my daughter, Becky, on vacations. When my son, Tracy, came along, they took him as well. My parents ended up with a car full of people, but it was truly a car full of love.”

“Daddy worked at DuPont for 35 years and was never late for work a day of his life. He was the most punctual person I ever knew. If he said he would be ready to go at 8:02, you had better be ready at exactly 8:02!”

“I don’t think I ever saw my father walk up a flight up stairs. He always ran. I guess that is what kept him young. When he was in his 80s, folks thought he was only in his early 60s. Daddy was in the hospital for congestive heart failure the night he died. He had sat up in bed with his Atlanta Braves baseball hat on and watched the entire ball game. It ended at midnight, and he passed away at 1:00 am. He was buried with his drumsticks in his hands and a dollar in his pocket. He always said, ‘You never know when a fellow might need a dollar.'”

“My father could not have had a happier, more fun-filled life. He knew he was an exception to have had such a poor start in early life, but knew his life had been filled with so much happiness and love that could not have been bought with money. He truly loved his wife, daughter, grandchildren and nephew without reservation. Having worked in the cotton mill as a child was not a detriment. He loved life and lived it to the fullest.”

In her interview, Jean Tomes says:

“Daddy was in the hospital for congestive heart failure the night he died. He had sat up in bed with his Atlanta Braves baseball hat on and watched the entire ball game. It ended at midnight, and he passed away at 1:00 am.”

So I looked up the game, which would have taken place on April 24, 1993. I found the score on the Baseball Almanac website. I emailed her the happy news.

“In the game your father watched the night that he died, the Braves beat the St. Louis Cardinals 11-0.”

*Story published in 2009.