Lewis Hine caption: Solomon Sickle, 11 yr. old gum vendor, 321 Seventh St., Washington, D.C., Says he sells until 8 P.M. Very illiterate, been in this country only six months. Location: Washington (D.C.), District of Columbia, April 1912.

“He came from rural Russia, and he was only in the US for six months, and here’s this man, a perfect stranger, holding this big camera in front of him. I wonder how he felt about that, because when he and his family came to America, they had to steal across the Russian border to get to Germany so they could get on the ship that took them to America.” -Sally Riskin, daughter of Solomon Sickle

“The street trades of Washington employ one-fourth of the total number of children engaged in all occupations. It is a surprising fact that of the number of children under fifteen who have come within the arm of the law, more than two-thirds are from the ranks of children in these trades. The boys selling papers are especially subjected to temptations. These youngsters, some of them seven and eight years old, quickly learn that it is much easier to make money by failing to have the correct change than to be content with the legitimate profit on the sale. Knowledge of sharp practice when acquired is hard to eradicate. The tendency is for the child to learn to believe that through begging or questionable means he can reap a larger harvest than is possible legitimately.” –Washington Post, April 2, 1908

**************************

In the summer of 1908, the US Congress, having jurisdiction over the District of Columbia, passed the first federally enacted child labor law. Among the provisions was the requirement that “no boy under ten and no girl under sixteen shall be permitted to be a bootblack (shoeshiner) or sell papers or goods of any kind on the streets or any public place in the District.” (Washington Post, May 22, 1908.)

The law also specified: “…no child under fourteen years shall be permitted to work unless the labor of such child is necessary for its support or for the assistance of a disabled father or mother or for the support of a younger brother or sister or a widowed mother. No child under sixteen years shall be employed unless authorized by the superintendent of public schools.” (Washington Post, June 7, 1908.)

In April of 1912, Lewis Hine took nearly 50 photographs of newsboys and gum vendors in Washington, and then submitted the following report to Congress as evidence of abuses of the 1908 child labor legislation:

“At various times, the streets literally swarmed with youngsters, a few of them five or six years old, many of them from 7 to 12. It was impossible for me to count, or even to estimate the number of them accurately, in the limited time I was in the city, because of the irregularity of employment and the vacillation of the children from place to place.”

In all of the Lewis Hine child labor photos, we see a child (or children) in a situation the photographer wants us to think about, and then come to the conclusion that it is not acceptable, and that there should be laws to prevent it from happening anymore. For this photo, we can tell that Solomon Sickle is young, perhaps 11 years old, as Hine stated. We know it’s daytime, but we don’t know what time of day. We don’t know where he is standing, except that it’s in Washington, DC. (According to Washington Seen: A Photographic History, 1875-1965, the location was near the corner of Seventh St and Pennsylvania Ave, NW.)

We don’t how many hours he’s been out there, or how many days of the week he does it. We don’t know if he goes to school, what language he speaks, who his parents are (or if his parents are alive), and how many siblings he has. And more importantly, we don’t know what he is thinking. Chances are, we will react with sympathy and wonder if this poor boy will ever get a chance at success in life.

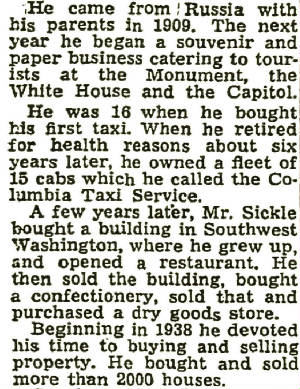

Solomon Sickle was born in Russia on July 5, 1903, according to the Social Security Death Index, but the family estimates he was born in 1901. He was one of at least six children born to Harry and Annie Sickle, who married in about 1895. Harry came to the US from Russia, without his family, in about 1908 (I could not find him or any of his family in immigration records). In the 1910 census, he is listed as a shoemaker with his own store, and lives at 321 7th Street. The rest of the family joined him apparently in 1911 or 1912 (per Hine caption and 1920 census), or perhaps as early as 1909, according to Solomon’s obituary. In the 1920 census, the family lives in a rented apartment at 309 Seventh Street, SW. Harry is still a shoemaker, and Solomon is listed as unemployed.

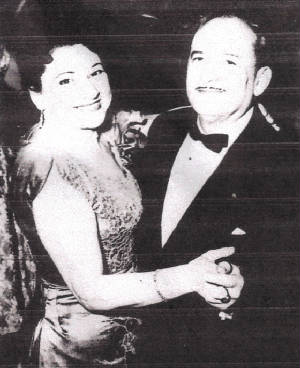

Solomon married Lillian Rosenthal about 1926, according to the 1930 census, which lists the family as having two young children and renting at 909 4 ½ Street. Solomon is listed as the owner of a delicatessen. At that time, his parents were living in their own home at 429 7th Street. His father was still a shoemaker. He died in 1940, at the age of 70. Solomon’s mother died in 1956.

Solomon Sickle passed away in Washington on June 30, 1956, at the age of about 55. I found his death record and obituary and contacted his daughter, Sally Riskin. She was stunned to see the photo of her father.

Edited interview with Sally Riskin (SR), daughter of Solomon Sickle. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on January 8, 2008.

JM: What did you think when you first saw the photo I sent to you?

SR: I was numb, happy and touched. I cried, seeing him as a little waif. If you hadn’t sent it to me, I never would have seen my father as a little boy. I blew it up and noticed that he had one eye closed, probably because of the sun. He came from rural Russia, and he was only in the US for six months, and here’s this man, a perfect stranger, holding a big camera in front of him. I wonder how he felt about that, because when he and his family came to America, they had to steal across the Russian border to get to Germany so they could get on the ship that took them to America. Had they been caught, my grandmother and her four little children would have been shot and killed by the Russians. My grandfather came over about five years earlier, and it took him all that time to get enough money to bring the family to Washington. His name was Harry. I don’t know the Jewish or Russian name. As soon as my grandmother got over here, she and my grandfather had twins.

JM: Did your grandparents speak Yiddish?

SR: Yes. My grandmother, whose name was Annie Esther Sickle, had never heard one word of English in her life. But she came to this country at about the age of 30, and she learned the language and became a citizen.

JM: Did you have any idea that your father would have been a gum vendor on the streets of Washington at the age of 11?

SR: Well, I heard that he was trading while he was on the ship coming over. He told me that he sold souvenirs at parades, but not how old he was when he did it. I wonder where he was when the picture was taken.

JM: The caption seems to say that he lived at 321 Seventh Street.

SR: It was probably in Southwest Washington, because I think the address of his first house was 429 Seventh Street, SW. His parents’ house was like a mansion, with a magnificent banister that we used to slide down. It had a balcony and wrought iron, like a New Orleans house. It was finally torn town by the city. Before the immigrants came, the houses in the neighborhood were lived in by very wealthy people. My grandmother’s house was built by Swing, the coffee people. He had his business there. There was a store in the back, where my oldest uncle operated a cleaners.

JM: Did your father graduate from high school?

SR: He went as far as the sixth grade.

JM: What did he do during his adolescent years?

SR: I know he had a car, but he was too young to drive it, so he hired some guys and started a taxi company. My father was a big jokester. He told me about some of the tricks that they played. There was a man who was playing around with some woman, and they told him that a woman was in the garage waiting for him. The doors were made of tin. After he went in there, the guys threw rocks at the door, and one of them yelled, ‘Who’s in there with my wife?’

He also had a sightseeing limousine. Then he opened a grocery store with his oldest brother, Henry. He was the most educated of the children, but my father was the most successful. There was a street called 4 ½ Street, SW. It was all shops. He opened up a candy kitchen there. He had married my mother by then. Her name was Lillian Rosenthal. Then he opened up a restaurant at Fourth and N Streets. My father liked to joke that he called it, Eat Here and Die in the Alley. He was very funny. He was very good looking, very kind, very sharp and a real go-getter.

JM: What was the real name of the restaurant?

SR: I don’t remember. One business that he owned was called the Metropolitan, but I don’t know which one that was. He also went into the clothing store business. He had a clothing store in Southeast Washington, across the street from the Marines barracks (Eighth and I Streets). Then he had a little grocery store in Northeast Washington. That was when I was growing up.

JM: When were you born?

SR: 1930.

JM: Where were your parents living then?

SR: They lived in an apartment in Northwest. Then they moved to 4 ½ Street, SE, where he had the candy kitchen. Then they moved to M Street, SW. That’s where he had the restaurant. While he was in the clothing store, he started buying real estate. And then we moved to Northeast Washington, on Twelfth Street, and he opened a real estate office. My father could tell you everything about real estate, but he didn’t have the education to pass the test. He became a speculator. He used to wholesale houses to the retail people in real estate. And then my husband came along, and he said, ‘Hey, Dad, why don’t we retail them?’ So my husband became the youngest real estate broker in Washington. My father did that until he died.

When we had the store on Twelfth Street, across the street, there was a cleaners. A very refined classy black man ran it. I used to walk past his shop on the way to school, and he would say, ‘Here comes Sally Sol,’ which is my name and my father’s name together. He was called Sol for Solomon. I used to go over to his shop and read the funnies. He loved crabs, but because he was black, he couldn’t go in the restaurants on H Street to buy the crabs. So he used to send me there to buy them, and we’d sit outside in front of his shop and eat crabs. It was like he adopted me and I adopted him. Years later, I found out that my father actually owned the building, and he was renting it to him.

JM: Where was your father living when he died?

SR: On Kansas Ave, NW. He owned the house.

JM: Your father died pretty young.

SR: He had a heart attack and died a couple of years later, in 1956. He was only 55. His unveiling was a year later, which is a Jewish tradition. My grandmother died four months after he did. That was a horrendous year for me. I adored her, and I adored him. They were good people. If my grandmother had one slice of bread, and you came along and you were hungry, she’d give you half of it, even if she didn’t know you.

In the 1950s, there was a real estate man, who shall remain nameless, and for some reason or another, he got into some kind of trouble. He lost face among his peers. At my father’s funeral, he stood there and looked at my father’s body and said that my father had stood by him when everybody else abandoned him, and that my father had given him money to live on. He was crying, and then when he finished talking, he leaned over and kissed my father on the cheek.

JM: When did your mother die?

SR: She died just 10 years ago. She was 91. She was still living in DC when I moved her to an assisted living place in Silver Spring (Maryland).

JM: How long did you stay around Washington?

SR: I just moved here to Florida five years ago. I had been living in Bethesda (Maryland).

JM: Did your mother ever work outside of the home?

SR: She worked with my father in his stores. Then she worked in a clothing store after he passed away.

JM: Did you work in any of your father’s stores?

SR: Yes, in the clothing store.

JM: Did you go to college?

SR: I graduated from Eastern High School, and then I went to Strayer’s Business College.

JM: What do you think about the fact that your father was selling gum on the street at such a young age?

SR: One of my cousins was very touched by the picture. He said, ‘Your father was really respected, even though he had only a little bit of education. The caption says he was illiterate, but look at what he became.’ My cousin told me that his grandfather was a tough guy and expected his children to go out and work. But my grandparents were not like that. My grandfather owned a shoe repair shop, and though they weren’t that well off, they would never have made my father go to work. They wouldn’t have told him, ‘You’ve got to go out and bring money home.’ It would have been his idea.

Here was a little boy from Russia that was able to go out there and sell something. He was out there till 8:00 at night. How did he know how to do that? He probably didn’t even know how to speak English. When he grew up, he was respected by his peers. I’ve always been in awe of him and his whole background, and his guts, and the way he would just go out and do things. He lived the American Dream. He couldn’t have done that in Russia.

Solomon Sickle: 1901-1956

*Story published in 2010.