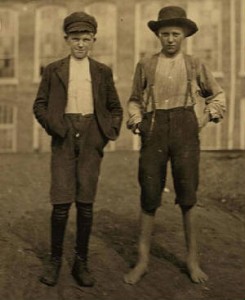

Lewis Hine caption: Willie Crocker, (barefoot) Wylie Mill, Chester, S.C. 13 years old– “worked since I was 6 years old.” Lost part of finger in gear of machinery. Fred Crocker–11 years old. 1 year in mill. Location: Chester, South Carolina, November 1908.

“I never knew my grandfather. He deserted my mother. He was married to my grandmother, Essie Crocker, who was seven months pregnant with my mother when he took off.” -Judy Marshall, granddaughter of William Crocker

“He (William Crocker) often told the story that when he was young, he was drinking, got a gun, went into the mills, and shot up the looms. But later, he got saved and became an itinerant preacher. -Charlotte Hobbs, wife of the minister of William Crocker’s church

“My father was a very kind man, very soft spoken. My mother and father were married 46 years, and I never heard them raise their voices.” -Nadine Nesbitt, daughter of Fred Crocker

“Thanks to these poor children who were photographed, child labor laws were enacted. Being forced to work instead of going to school is most certainly why Fred never learned to read or write.” -Nancy Meissner, niece of Fred Crocker

**************************

In 1888, investors, including J.L. Agurs and T.H. White, opened the Chester Manufacturing Company, the town’s first cotton mill. In 1900, they opened the Wylie Mill, which eventually became part of Springs Industries, a large and ever-expanding textiles manufacturer. In 1975, then called the Gayle Mill, it closed permanently.

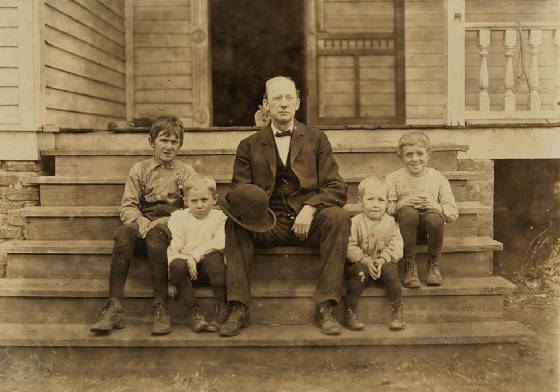

Lewis Hine caption: Wylie Mill, Chester, S.C. Plenty of young children. Location: Chester, South Carolina, November 1908.

“In general, I found these (mills) in South Carolina were considerably worse than conditions in North Carolina, both as to the age and number of small children employed, though several of the mill towns in North Carolina approached the worst ones in South Carolina. In Chester, South Carolina, an overseer told me frankly that manufacturers all over the South evaded the child labor law by letting youngsters who are under age help older brothers and sisters. The names of the younger ones do not appear on the company books and the pay goes to the older child who is above twelve.” -Lewis Hine, from a 1909 National Child Labor Committee report

Lewis Hine caption: Mr. Smith, overseer in Wylie Mill, Chester, S.C. He will not let his children work in the mill. Says it is no place for them. Plenty of children below 12 in his mill. He said that it is a common practice all through the South for employers in cotton mills to evade the child labor law by allowing young children to help their older sisters or brothers. The name of the small child is not on the books. “That is the way we manage it.” Nov. 28/08. Location: Chester, South Carolina.

The first thing that strikes me about this photograph is how differently these boys present themselves. Fred looks friendly and composed, and he is nicely dressed. William, barefoot and sloppily dressed, looks almost defiant, although perhaps more typically like a young adolescent. When I see a Hine photo, I often wonder whether the image Hine captured somehow gives us a hint of what the child will be like as an adult. I have encountered a number of startling examples of this happening; and in this case, he seems to have been right on the nose for both boys.

In the case of William, this has to be one of the strangest stories I have come across in my research. Much of what I found out was a huge surprise to his descendants and friends. That’s because he was married twice (no children from the second), but no one I talked to knew about both marriages, only either the first or the second. His niece, the daughter of his brother Fred, was astonished and had a hard time believing it. She knew only about the second marriage, as did William’s close friends from his church. But to Judy Marshall, the granddaughter from the first marriage, it was a revelation that provided a missing link and helped to reconcile her feelings toward her grandfather who had abandoned her mother as a child.

William Massie Crocker was born on December 18, 1894, in Chester, South Carolina. His parents were Aaron Walker Crocker (known as Walker) and Sallie (Jameson) Crocker, who were married about 1892. According to the 1900 census, they were living in Chester. Walker was a farmer, and they had four children, William being the second oldest. In the 1910 census, still in Chester, they had two additional children. Walker is listed as an engineer in a cotton mill, and three sons, including William, are doffers at the mill.

In the 1920 census, William is now married to Essie (Smith), and they live with William’s parents and four of his siblings. Both William and Essie work at the mill, he a carder, and she a weaver. But they are now residing in Whitmire, South Carolina, about 30 miles southeast of Chester. In 1923, William and Essie had their first and only child, Novilla; but according to Novilla’s daughter, William left the home a few months before Novilla was born, and the couple divorced soon after.

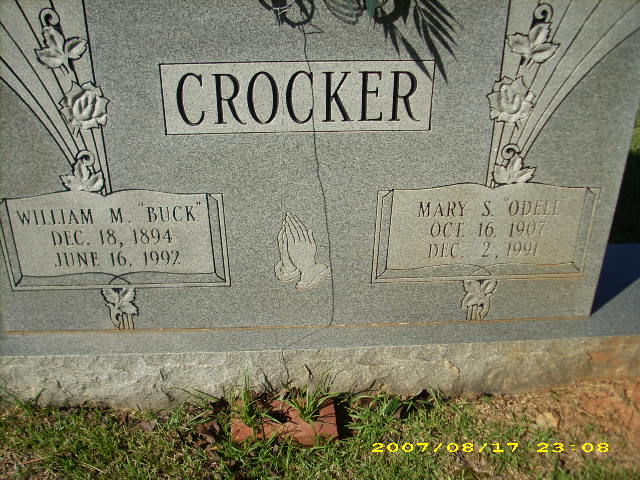

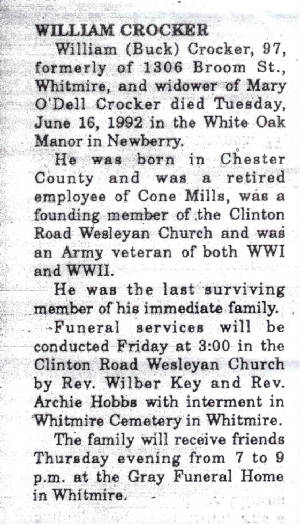

In the 1930 census, Essie is back in Chester, living with daughter Novilla. They are boarding with an unrelated family, and Essie is a weaver in a cotton mill. She is listed as widowed, but it was common at that time for divorced women to claim they were widows. Indeed, William was still living, probably in Whitmire, although I could not find him in the 1930 census. Sometime after 1930, William married Mary S. O’Dell and lived the rest of his life in Whitmire. They had no children. He served in both WWI and WWII, and worked many years at Cone Mills.

William’s father, Walker Crocker, died in 1928, and his mother, Sallie, died in 1961. His wife Mary, called Odell or Dell by friends, died December 2, 1991, at the age of 84. William, long since known as Buck, died on June 16, 1992, at the age of 97. His daughter Novilla, then Novilla Davis, died in Catawba, South Carolina in 2004, at the age of 80. According to her daughter, she had not seen her father since she was five years old. But that’s not the whole story.

The following is edited from an interview and some email correspondence in the summer of 2008, with Judy Marshall, granddaughter of William Crocker.

JM: What do you know about your grandfather?

Judy: I never knew him. He deserted my mother. He was married to my grandmother Essie, who was seven months pregnant with my mother when he took off. When my mother was five years old, she saw him at a funeral. One of the relatives told her: ‘That man over there is your daddy. If you go over there and give him a hug, I’ll give you a nickel.’ My grandmother stepped in and said, ‘If she goes over there, I’ll give her a whipping.’

JM: That’s interesting, because William’s father, your great-grandfather, died on February 9, 1928, and was buried the next day. Your mother would have been five years old then. That must have been the funeral where your mother saw him.

Judy: That was the closest my mother ever got to him. She wrote to him after she got married, but he never responded to her letters. She spent her whole life hoping that he would contact her, but he never did. We heard he was a minister. I guess he had to protect his second family and his church. What would they think of him, their minister, if they found out that he had a child? His second wife may have known about it.

Several months later, after I had found out about William’s other marriage and how his life turned out, I contacted Judy again by email and told her the information. This was her reply:

“Thanks so much for what you have done. I was pleased to hear that he served in WWI and WWII. I bet he was a nice man. I cannot stop thinking of my grandfather and what his life must have been like. You have provided me and my siblings with a missing link. I hope he was happy through the years. My own daddy died when I was seven years old, so I pretty much grew up with just one male figure, Daddy’s dad. I think my mother’s life would have been less of a struggle if she would have had her father in her life, especially since Essie died when my mother was so young. Sadly we will never know what happened between William and Essie. I don’t think either of them had any idea of the void my mother felt. I guess he was a good man, but he missed out on a lot not knowing my mother. She was a beautiful and loving person.”

“We called them Uncle Buck and Aunt Dell. They were wonderful people. They were almost like parents to us. They had young minds, and when we went on a shopping trip out of town, they would go with us. When Buck was a preacher, he had a car with a speaker on top of it, and he went around and held revivals in the area. He couldn’t read, but his wife read scripture.” -Charlotte Hobbs, wife of the minister of William Crocker’s church

**************************

Fred Crocker

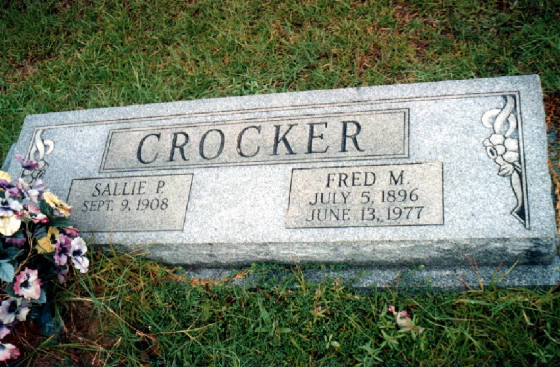

Fred Mathews Crocker, the well dressed brother of William, was born on July 5, 1896. In the 1930 census, he is listed as living in Kershaw, South Carolina. He is single, and working as a spooler in a cotton mill. Shortly after, he married Sallie Player, and they had their first and only child, Nadine Crocker (now Nesbitt). Fred worked in mills for many years. Wife Sallie did as well, both as a child and an adult. Fred died on June 13, 1977, at the age of 80. Sallie died in 1994 at the age of 87.

I managed to find daughter Nadine, living in South Carolina, and I sent her the photo of her father and his brother. She was excited to get it.

Edited interview with Nadine Nesbitt (NN), daughter of Fred Crocker and niece of William Crocker. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on July 18, 2008.

JM: Were you surprised by the photograph?

NN: I was blown away.

JM: Had you ever seen a picture of your father at that age?

NN: No. The earliest picture I ever saw of him was taken during WWI.

JM: Had you ever seen a picture of his brother William?

NN: Not from that time.

JM: Did you know that your father worked at the Wylie Mill when he was young?

NN: Yes, he told me about that. He told me that he bought a pair of shoes with his first paycheck, but his father made him take the shoes back and give the money to him, because everything that they made had to go to the family.

JM: It’s funny that you mention the shoes, because in the picture, it’s his brother who is barefoot.

NN: Maybe my father finally got those shoes.

JM: In the picture, your father looks well dressed, but his brother looks pretty messy.

NN: I think they look like Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn.

JM: What did your father do when he grew up?

NN: He continued to work in mills. He retired when he was about 62, from the Wateree Mill, once called the Kendall Company. That was in Camden, South Carolina. He worked in the card room. He usually worked the day shift, but sometimes he worked nights.

JM: So when you were growing up, you remember him working there?

NN: Yes.

JM: Did you ever go down to the mill to see him?

NN: Oh, yes. Me and my friends who grew up the village just about lived in that mill. We played in the mill.

JM: Did you work at the mill?

NN: No.

JM: How many brothers and sisters did you have?

NN: None. I was an only child.

JM: What was your mother’s name?

NN: Sallie Claire Player Crocker.

JM: Did she work?

NN: Yes, at the same mill.

JM: What was your father like?

NN: My father was a very kind man, very soft spoken. My mother and father were married 46 years, and I never heard them raise their voices.

JM: What things did he like to do when he wasn’t working?

NN: He loved to fish and hunt, and he was very interested in politics.

JM: How far did he get in school?

NN: He never went to school. In later years, he learned to read and write his name. I think he could read some, because he looked at the newspaper and seemed to know what it said.

JM: When he was in WWI, did he go overseas?

NN: Yes, he was wounded in France. He was in a hospital in Belgium when the war ended.

JM: Your father lived a long time. He was 80 when he died.

NN: All the children in my father’s family lived to be old. His brother Toy was almost 100 when he died.

In my interview with Fred’s daughter, Nadine Nesbitt, I told her about the first marriage of her Uncle William, and his daughter from that marriage. She was very surprised.

JM: William lived to be 97. What can you tell me about him?

NN: I know he worked in the mill. Later, I think he was a Methodist minister. He and his wife never had any children. We always called him Buck. I didn’t know him very well, because he lived in Whitmire, and we lived in Camden. Back then, you didn’t visit that often.

JM: Was he married more than once?

NN: No, just one time.

JM: I have information that indicates that he was married twice.

NN: Really?

JM: Yes. Sometimes when you do this kind of research, you find things that the family doesn’t know about. I found out that when he was young, he married Essie Smith.

NN: We called his wife Odell.

JM: In his obituary, William’s wife was Odell, his second wife. His first marriage was to Essie Smith. Apparently, that is the marriage you don’t know about. He and Essie married in 1920 and got divorced, probably before 1930, before you were born. They had a daughter named Novilla. I found her obituary, too. She was born in May of 1923, and she died in 2004. Her name was Novilla Davis when she died. The obituary says, ‘A native of Whitmire, Mrs. Davis was the daughter of the late William Crocker and Essie Smith Crocker.’

NN: That is really odd.

JM: I talked to Novilla’s daughter. She told me that her mother often talked about the fact that her mother’s parents, William and Essie, had divorced when she was very young, that her father remarried, that his nickname was Buck, and that he and his second wife did not have any children. She had heard that her father was a minister and often travelled around from town to town, like an evangelist. When Novilla died, she had not seen her father since she was a child. I found William in the 1920 census, listed as about 25 years old and married to Essie, and they are living with his parents. Your father was also living in the home. In the 1930 census, Essie is listed as living with her daughter Novilla, but she is no longer living with William. Essie is listed as a widow, but it was common in those days for a divorced woman to tell the census taker that she was a widow instead.

NN: That’s really strange.

JM: So it looks like he has to be the same William Buck Crocker who was your uncle. I guess he was just young and his marriage didn’t work out, and he regretted it, tried to keep it quiet, and move on with his life.

NN: You would think that someone in the family would have let the cat out of the bag.

*Story published in 2010.