“I heard Erroll Garner play it when I was in my teens. There were no lyrics yet. I blurted out, ‘Mr. Garner, I am going to record your song if I ever make a record.'” -Johnny Mathis

“Look at me/I’m as helpless as a kitten up a tree.”

I was sitting in my favorite diner listening to the jukebox when I first heard Johnny Mathis sing these words, and that is exactly the way I felt at that moment. I was not hopelessly in love, as the lyrics go on to explain, I was lonely. It was my freshman year of college, and I was living away from home for the first time. Less than three months into my first semester, I already knew I didn’t fit in.

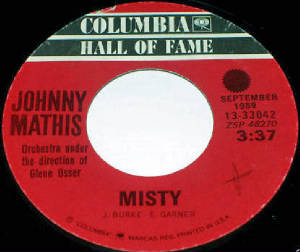

It was a cold November night, but Johnny’s romantic voice, the shimmering orchestral arrangement, and the haunting, echoey sound of the recording felt like a warm sweater. I ordered another burger and a coffee refill, and played “Misty” four more times. Five decades later, it’s my favorite record of all time, and the one that remains the standard bearer in Mathis’s vast catalogue.

Last November (2009), serendipitously exactly 50 years since the record became a hit, I decided I wanted to find out why and how the record was made, hoping against hope that I could track down at least a few of the people who had a hand in creating it. Within weeks, I had interviewed Glenn Osser, the arranger; Frank Laico, the sound engineer; Andrew Ackers, the son of the late Andy Ackers, the piano player on the session; Mary Burke Kramer, the widow of lyricist Johnny Burke; and the great Mr. Mathis himself. All were delightful to talk to and full of information they were happy to share.

The renowned jazz pianist Erroll Garner was known for his elaborate introductions, and his complex and ornamental improvisations. He died in 1977. He often said that he composed the melody for “Misty” while on a long plane ride. He looked out the windows at the high clouds and the tune came to him. Garner, a self-taught musician who could not read or write music, memorized it and worked it out on the piano when he got home. He played it in clubs for a while, and then recorded it in one take for the 1954 album Contrasts.

The beautiful harmonic structure of “Misty” resembles the compositions of jazz-influenced songwriters such as George Gershwin, Harold Arlen and Duke Ellington. However, it was not a good candidate for lyrics, since its nearly two-octave range presents a challenge for most singers. Nevertheless, songwriter Johnny Burke did precisely that several years later, with marvelous results.

The youthful excitement of falling in love is brilliantly captured by Burke’s seductive words. The key line comes at the opening of the bridge: “You can say that you’re leading me on/But it’s just what I want you to do.” This lets the listener know that the object of the singer’s affection is apparently interested, too. And finally, the premise suits both the mood of the melody and the title he had to work with. No surprise here, given his track record. When he died in 1974, he left a legacy of dozens of standards such as “Pennies From Heaven,” “It Could Happen To You,” and “Like Someone In Love.” I asked Mary Burke Kramer how her late husband wound up writing the words to “Misty.”

“I wasn’t married to Johnny when that happened. The story that I heard was that he had been working every day with his pianist, Herb Mesick, who was helping him put things down on paper. Herb had heard the melody to ‘Misty,’ and knew Erroll Garner, and was very fond of it. He told Johnny about it, but by that time, Johnny had made a decision not to collaborate anymore. After he and Jimmy Van Heusen had separated, on good terms, he had been working on his own writing both music and lyrics. Herb was very persistent. Whenever Johnny would enter the room, Herb would start playing the tune. Finally, Johnny said, ‘Alright, give me the damn music, and I’ll do it.'”

“So he went into the bedroom, and two or three hours later, he came out with the lyrics. He presented it to Frank Military at Warner Chappell Music Publishing, and Frank suggested a couple of lyric changes. Johnny just told him to take it or leave it as is, and then said, ‘If it ever winds up being a hit, I’ll buy you a suit.’ Well, of course, it became one of his biggest hits.”

In 1957, “Misty” was recorded by singer Dakota Staton, but it wasn’t until Sarah Vaughan recorded it in 1958, for the album, Vaughan and Violins, arranged by Quincy Jones, that the song began to attract serious attention. It was a perfect vehicle for Vaughan’s jazz stylings and multi-octave range. Among those who heard it was Mathis.

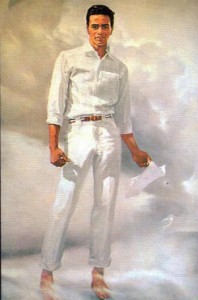

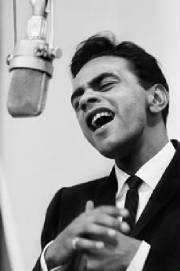

In 1956, at the age of 21, Mathis was signed by Columbia Records after being discovered by producer George Avakian, who saw him singing jazz at San Francisco’s famous night club, the Black Hawk. But after recording an unsuccessful first album, Columbia was not sure what to do with him.

“I had gone through the process of finding out what kind of records I was going to make,” Mathis recalls. “The first album, called A New Sound in Popular Song, was basically a lot of jazz musicians getting together with charts and me singing every note that I could, trying to be relevant, and not really knowing what I was doing. But then I got some help from Mitch Miller (head of Columbia’s Artists and Repertoire Dept), who took me in a direction that seemed to suit my voice better, with very romantic songs that I didn’t really vocalize like a jazz singer, I just sang them.”

“I recorded an album with (arranger) Percy Faith and some singles with (arranger) Ray Conniff. By then, I wanted to do songs that I had been listening to by iconic singers such as Sarah Vaughan and Ella Fitzgerald. That led to doing the album called Heavenly.”

Mathis was told to pick out 20 potential songs, demo them with just a guitar, and give the demos to arranger Glenn Osser. Among the songs he chose was “Misty.”

“I heard Erroll Garner play it when I was in my teens. I was frequenting the Black Hawk, where Erroll played three or four times a year. One night, he played the tune. There were no lyrics yet. I liked it a lot. I blurted out, ‘Mr. Garner, I am going to record your song if I ever make a record.’ Several years later, Johnny Burke had written lyrics to it, and I had fallen in love with Sarah Vaughan’s version.”

“Erroll’s business manager, Martha Glaser, heard somehow that I was going to record it, and she showed up at the recording studio. But we had a little problem, because I was told to record a song from one of the current Broadway shows, for which Columbia was planning to do the original cast recordings. That was going to push ‘Misty’ out.”

“By the time we got to the last song, which was ‘Misty,’ someone reminded me that I was also obligated to sing one of those Broadway show songs, and so we had a little argument over that. I said, ‘Let’s just do ‘Misty,’ and then I’ll sing the other song, and we’ll see which one comes out better.’ So Mitch asked Glenn Osser to do the chart. When I sang ‘Misty’, I remember the oboe solo, and that I just sort of came in at the wrong time with that high note. Well, it turned out later to be a famous moment in the song. Looking back now, it was wonderful that it happened sort of accidentally on purpose.”

Mathis was referring to his full-octave fade-in glissando (sliding down the scale) when he sings “On my own,” as he comes back in after the instrumental break. It was his idea, and the only way he could do it was to stand a distance from the microphone and gradually walk toward it.

“I used that device a lot back then. They couldn’t do it technically in the studio, so if you wanted it done, you had to do it yourself. What you did in those days was often very much off the cuff. Since you did the recordings entirely live, you had only one chance to sing the song. When you have to do four songs in three hours, which was what we did in those days, you really don’t have much time to do anything more than what comes natural to you. If it works, it works; if it doesn’t work, it’s still going to get released.”

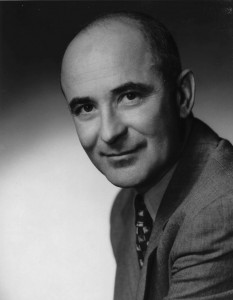

Osser was a seasoned staff arranger who had been writing arrangements since 1937, many for big band stars such as Benny Goodman and Bob Crosby. More recently, he had worked with singers Vic Damone and Jerry Vale. As it turned out, he and Mathis were a perfect match. Now 95 years old, Osser recited the details of his classic arrangement for “Misty,” as if it were just yesterday.

“I knew that it had been written by Erroll Garner, so I started off the arrangement with the piano, on account of him. Then I decided that I wasn’t going to have any violins come in until the second verse, when Johnny sings, ‘And a thousand violins begin to play.'”

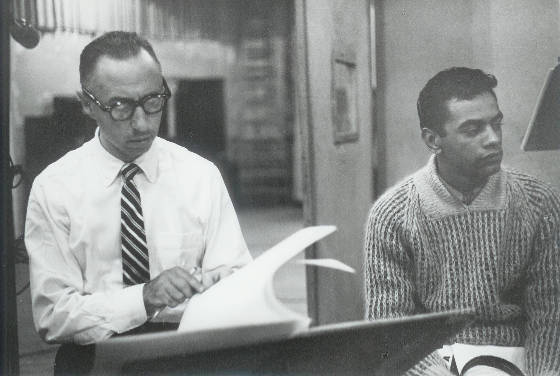

Andy Ackers was the piano player on the session, and his introduction and fills played a prominent role in the recording. I asked Osser if Ackers was improvising.

“It was all written out. If you listen to it closely, Andy played block chords and the guitar played the lower notes in unison, just like in the George Shearing Quintet arrangements, except that I didn’t use a vibraphone. Usually, when I do an introduction, I try to incorporate the main theme, paraphrased in some way. But this is one time that I didn’t; it was a completely new composition. Behind it, I had the rhythm section and some violas and cellos sustaining harmony, just as a little cushion. When I wrote out those piano fills for Andy, he said, ‘I’ll play anything you want.’ He was one of the best players for being able to do that in exactly the right style. I had him on so many dates.”

Ackers was also a veteran of the big bands, as well as a busy songwriter. In the late 1940s, he stopped going on the road and became a highly gifted studio pianist who played on perhaps a thousand or more records with everyone from Tony Bennett to Brenda Lee. He also played on numerous television commercials, and even on many Musak recordings. He died in 1978. His son Andrew, also a musician and composer, grew up fully aware of his father’s talent.

“I was just listening to ‘Misty’ last night,” he told me, “and I enjoyed it more now than I ever have, since you brought it out to me. Johnny’s singing was so spectacular. He had a beautiful voice and a beautiful style. Of course, Dad would have been playing a written score, but I loved his style of playing it. It was so meaningful. He didn’t roll the chords. There were little subtle touches that were examples of my father’s sensitivity.”

“With the Internet now, I am able to hear a lot of the records that my father played on. And I can recognize my father’s style. Compared to my father, almost every other studio pianist was mechanical. He had a very musical way of pacing. You think of an ocean and its waves going higher and lower, and that describes my dad’s playing. He wasn’t just playing the notes as they were written. There was another pianist who competed with him named Bernie Leighton. He was the only other studio pianist with the caliber of my dad. They were friends. But even Bernie didn’t play with the same sensitivity. In fact, I can almost always recognize my father on piano when I hear something that he played on. I remember one time when I was getting a haircut. They were playing Musak in the background. All of a sudden I heard this piece I had never heard before, listened to the piano part like you did in ‘Misty,’ and said to myself, ‘That’s my dad.'”

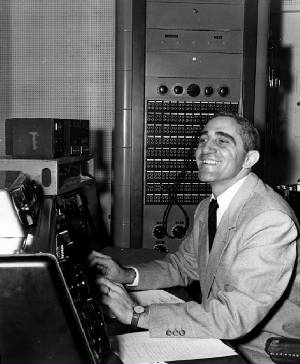

Great recordings such as “Misty” would not have been possible without the services of sound engineer Frank Laico, now 92, who along with Mitch Miller, created the legendary 30th Street Studio where Columbia recorded most of its best albums. Laico’s long association with Tony Bennett, and his work on memorable original cast recordings such as West Side Story only scratch the surface in describing his contributions to the recording industry. It was Laico who worked with Mathis in the studio to find the best way to record his voice.

“When Columbia started the studio on 30th, Mitch and I found an empty room in the basement that was just storing junk,” said Laico. “We emptied it out and spent quite a bit of time with microphones and speakers to make our own echo chamber. Johnny had done two albums with Columbia previous to when I was asked to record him. We were looking for a sound that was going to sell records. We tried all kinds of things: equalization, echo, just about everything. I spent a good hour of the first session while the musicians just hung around. Finally, Mitch and I got the sound we wanted. At that point, we never changed the way we recorded him.”

Laico had a long association with Osser, and they remain friends.

“He arranged his charts as if he wrote the songs himself. He had such a clear idea how to make an interesting arrangement for any song. He did so many different kinds of songs. He’s a great artist. The recording of ‘Misty’ couldn’t have come out any better. Most of the time I did records, I was hearing, but I wasn’t paying attention to the lyrics or other little things. But this was one of those that I was really listening to.”

I asked Mathis if he thinks “Misty” represents his best work.

“It’s the song I am most proud of, because I did it myself. The other stuff was handled more or less by Mitch Miller or whoever was the producer of the moment. But I took it upon myself to do the tune the way I wanted to, and to have it actually become a signature moment in my musical career was the best thing that could have ever happened. I loved Erroll Garner so much. He was a wonderful musician, a genius really, because he couldn’t read music. He never played the song the same way. He had all these amazing inventions he played before he started playing the melody. I was so proud that I had heard the tune when I was very young when there were no words to it, and that I kept my promise to record it, and I did it in a way that would last over a couple of lifetimes.”

“‘Misty’ happens to be one of my favorites. Johnny Mathis used to call the house quite often and ask to speak to Johnny. He was crazy about him.” -Mary Burke Kramer, widow of Johnny Burke

**************************

On the following pages, see the complete interviews with sound engineer Frank Laico; arranger-conductor Glenn Osser; Andrew Ackers, the son of pianist Andy Ackers; and singer Johnny Mathis, plus sound samples and more photos.

Laico tells us more about working with Mathis in the studio. Osser talks about his incredible 75-year career, including colorful stories about working with Benny Goodman and Judy Garland, among others. Ackers gives us great insight about his father’s life as a unique and underrated musician. And finally, Mathis talks in depth about how he developed his singing style, and the music business people who mentored him.

**************************

Interview with sound engineer Frank Laico, conducted by Joe Manning on November 6, 2009.

Manning: Had you worked with Johnny Mathis before “Misty” was recorded?

Laico: Yes, but I didn’t do his first two albums. When I was asked to record him, Mitch Miller and I worked in the studio trying to get the right sound on his voice.

Manning: What kind of a sound were you looking for?

Laico: A sound that was going to sell records. We tried all kinds of things: equalization, echo, just about everything. I spent a good hour of the first session while the musicians just hung around. Finally, Mitch and I got the sound we wanted. At that point, we never changed the way we recorded him.

Manning: What was different about your first album with him as compared to his first two albums?

Laico: He was trying to be a jazz singer, but the albums didn’t go anywhere. That’s when Mitch Miller stepped in and told Johnny he was going to work with him to do something different.

Manning: There is a lot of echo on “Misty.”

Laico: Yes, there is echo. When Columbia started the studio on 30th Street, Mitch and I found an empty room in the basement that was just storing junk. We emptied it out and spent quite a bit of time with microphones and speakers to make our own echo chamber.

Manning: Was Johnny patient with your experiments to get his voice to sound the way you wanted it?

Laico: Yes, he was patient. His manager, Helen Noga, made sure that he was patient. She kept him on a tight string. There was no problem. He was willing to keep going until we were satisfied.

Manning: When you were experimenting, was he actually singing the songs that were going to be on the album?

Laico: Oh, sure.

Manning: Did you have a long association with Glenn Osser?

Laico: Yes, I did.

Manning: What was special about his arrangements?

Laico: He arranged his charts as if he wrote the songs himself. He had such a clear idea how to make an interesting arrangement for any song. He did so many different kinds of songs. He’s a great artist.

Manning: When you were doing “Misty,” did you think it was going to turn out to be something that would wind up being special?

Laico: Well, it couldn’t have come out any better. Most of the time I did records, I was hearing, but I wasn’t paying attention to the lyrics or other little things. But this was one of those that I was really listening to.

Manning: Was “Misty” the biggest record you ever engineered?

Laico: I can’t say. I also did Tony Bennett’s “I Left My Heart in San Francisco.” But on those records, you would never see my name, because they would never give the engineers credit.

Interview with arranger-conductor Glenn Osser, conducted by Joe Manning on October 31, 2009.

Manning: How did you get the assignment for the Heavenly album?

Osser: For many years, I was a staff conductor for the American Broadcasting Company. In the late 1940s, there was this husband and wife team who wanted to do an audition for a half-hour radio show, and they had a singer named Vic Damone who was going to be featured on the show. I was assigned to be the music director, and that’s how I got to know Vic. When he got a chance to make a couple of recordings at Mercury Records, he called and asked me to do the arrangements. One of the songs we did was “You’re Breaking My Heart,” which turned out to be one of his biggest hits. Mitch Miller produced that. Then Mitch left Mercury and signed with Columbia, and got Vic to sign with Columbia, too. And then Mitch brought me to Columbia to work with Vic. I started doing records with other people as well. When they had the session for “Heavenly” with Johnny Mathis, Mitch Miller assigned me to it. I hadn’t worked with Johnny before that. Mitch told me it would be a bunch of pretty ballads, which Johnny would be picking out. Johnny sent me a tape of him singing them with just a guitar as accompaniment. That way, I would know the keys he was going to sing in, and how he was going to phrase them.

Manning: Was “Misty” on that tape?

Osser: Yes, and I knew that “Misty” had been written by Erroll Garner. So I started off the arrangement with the piano, on account of him. Then I decided that I wasn’t going to have any violins come in at all until the second verse, when Johnny sings, “And a thousand violins begin to play.” That business about him hitting that high note coming out of the instrumental break was his idea.

Manning: Johnny told me that he stood a few feet away from the microphone and then walked toward it so that his voice would fade in.

Osser: That’s right. When he first suggested it, he and Mitch and Frank Laico decided to try it that way, and it worked out well, so that’s what they did on the record. Johnny was able to control the glissando when he came to the part where he sings,”On my own.” He was a natural. There were a lot of things he could do with his phrasing. That’s why he became a big selling artist.

Manning: Andy Ackers played the piano on that session. Did he improvise his intro, or did you write it out?

Osser: It was all written out. If you listen to it closely, Andy played block chords and the guitar played the lower notes in unison, just like in the George Shearing Quintet arrangements, except that I didn’t use a vibraphone.

Manning: Was that piano intro directly influenced by Garner?

Osser: Only to the extent that I used the piano. Usually, when I do an introduction, I try to incorporate the main theme, paraphrased in some way. But this is one time that I didn’t; it was a completely new composition.

Manning: That intro seems to have become the signature for the recording. It sets a tone at the beginning, and it is so distinctive.

Osser: It was just one of those accidents that worked out.

Manning: In the first verse, there are just piano fills.

Osser: The rhythm section was playing, and just some violas and cellos sustaining harmony, just as a little cushion. I wrote out those piano fills for Andy, and he said, “I’ll play anything you want.” He was one of the best players for being able to do that in exactly the right style. I had him on so many dates.

Manning: In the second verse, the strings are now playing the fills, just like the piano did. They are sort of answering back to the singer, which was a typical device you used in your arrangements.

Osser: I always liked to do that.

Manning: There are a lot of things I’ve noticed about your style in listening to a number of records that you did. You often used a harp.

Osser: Oh, yes. I loved the harp.

Manning: And you seemed to be partial to muted trumpets and oboes.

Osser: I used a lot of oboes and flutes, and we got the great soloists to do them. They didn’t have to be swingers. We got the flute and oboe players from the New York Philharmonic.

Manning: At the end, when the vocal fades out, you throw in three two-note string phrases before the final piano notes, which are the first three notes of the verse.

Osser: I put a big four-bar ending on it instead of the usual two bars.

Manning: On the album, “Misty” seems to stand out. It’s a slightly different sounding recording than the other songs. There seems to be a bit more echo on it.

Osser: Columbia had a great studio and some terrific sound engineers such as Frank Laico.

Manning: Did you have any idea when you recorded “Misty” that it was going to turn out to be something really special?

Osser: No. I was surprised that it was a big hit. So was Columbia. If they had felt it was going to be a hit, they would have released it as a single right away. It turned out that some disc jockeys started playing it off the album, and it caught fire.

Manning: Did you continue to work with Mathis after the Heavenly album?

Osser: Sure. I did a number of albums with him. The next album we did was called Faithfully. The opening song of Heavenly was also called “Heavenly.” Burt Bacharach had written it. That was before Burt was writing the kinds of songs he was famous for. Because the album was such a hit, they called Burt and asked him to write another song. So he wrote “Faithfully.” The big hit from the album was “Maria,” from West Side Story.

Manning: Do you still keep in touch with Johnny?

Osser: He called me about 12 years ago. I hadn’t heard from him in a long time. He said he was going to do a Christmas concert tour, which would include a medley of Christmas songs. He asked me to write an overture – a medley of his hits – that the band would play before he came out and sang. He was doing a show in Long Island at that time, so I went out to one of his rehearsals and ran through it with him. That was the last time I saw him. He still uses that overture.

Manning: Was he the most successful singer you ever worked with?

Osser: Probably, but I think I made more albums with Jerry Vale. Most of the albums with him were all Italian songs. I used to conduct for his shows occasionally when he needed a sub for his regular conductor. Jerry talked a lot to his audience. He was a very good joke teller. When he would introduce me, he would say, “I made about six Italian albums, and all the arrangements were done by this nice Jewish boy.”

Manning: I have an obscure album that came out about 1961, by a young singer named Diana Trask. It’s been out of print for years, but it’s still one of my favorite albums. Diana sounded a lot like Eydie Gorme. I liked her, but it was your arrangements that made me buy it. Do you remember that album?

Osser: Of course. We had a great band on that session. She was about 19 at the time.

Manning: She did a bunch of standards on that album, including five songs by Richard Rodgers. Later on, she changed to country music and recorded in Nashville.

Osser: I was conducting for Jerry Vale in Las Vegas once, maybe in the mid-seventies, and she saw my name on the marquee; so after the show, she came to see me. She told me, “I loved the stuff we did together, but I’m making more money doing country songs.”

Manning: When you read about the history of the great vocal recordings of the 1950s and 1960s, the arrangers that always get mentioned are Nelson Riddle, Billy May and Gordon Jenkins. I seldom see you mentioned. I’ve always felt that was unfair, because I think you were one of the best.

Osser: Well, a lot of the stuff those guys worked on was with Frank (Sinatra). That’s one of the reasons they got so much recognition. With me, I made so many different kinds of records with so many people: Damone, Jerry Vale, Jill Corey, and so on. Some did well, some didn’t. I didn’t always get the biggest singers.

But I figured out once that I arranged eight singles that became number one on the charts. The first one was “You’re Breaking My Heart,” by Damone. The second one was “Kiss of Fire,” by Georgia Gibbs. The third was also by Georgia. It was a crappy song called “Tweedly Dee.” And I did the Roger Williams piano hit of “Autumn Leaves.” That was number one. That song put Dave Kapp in business. He got fired from RCA Victor as an A&R man, so he started his own company called Kapp Records, which was doing religious albums.

Dave was going to try to record a couple of pop singers, so he got Jane Morgan, and wanted to do four sides with her. He called me up and asked me to do the arrangements. He told me to go up to her apartment and work on it with her. I played the piano, and we went through a bunch of songs, but we could only find three that she liked.

So Dave said, “Forget it, we’ll do just three sides with her. I just made four sides with a piano player named Lou Weertz, with just a bass and drums. I changed his name to Roger Williams, and I’ve already released two of the sides, but I have one leftover. So I’ll bring him in when we record Jane, and we’ll do the tune, ‘Autumn Leaves.’ ”

So we went into the studio and Williams played it, and Dave says, “I would like to have something in the beginning that is attention getting.” So I said, “Well, you can’t beat the opening of Grieg’s Piano Concerto in A Minor.” So that’s what I used for the intro. I did a Jack Jones album with Dave also.

I did an album one time with Georgia Gibbs, and the producers, Hugo and Luigi, were out of town. The person who was supposed to write down all the information for the back of the record cover was supposed to make sure it said, “Orchestra conducted by Glenn Osser,” but she didn’t know my name. So the album came out, and it just said, “Georgia Gibbs, with orchestra.”

Manning: That reminds me of the story about Nat Cole’s recording of “Mona Lisa.” Nelson Riddle was a staff arranger for Capitol and did that wonderful arrangement for it, but on the record, the producer, Les Baxter, is credited instead.

Osser: I always thought that Axel Stordahl was a terrific arranger and didn’t get enough credit. He arranged a lot of Sinatra’s albums on Columbia, and one on Capitol when Sinatra signed with them (1953). He wrote a lot of lush arrangements. But they weren’t selling a lot of records. So they changed arrangers and brought in Nelson Riddle. His arrangements were more jazzy.

Talking about Sinatra, Jimmy Van Heusen was one of my best friends. Sinatra sang almost every song that Jimmy wrote. His real name was Chester Babcock, and he was from Syracuse. He took his last name from the shirt company. I came to New York in 1936, and met him in 1937, when he was working at Remick Music. They were always plugging songs. Bandleaders and singers would come up, and Jimmy would play the piano while someone would sing the songs they were plugging.

Manning: Did you have preferences about who you worked with?

Osser: No. Whatever they assigned me, I did.

Manning: Which did you prefer doing the most, ballads or uptempo numbers?

Osser: I liked to do ballads, although I loved jazz. When I was in college, jazz was so big then. When I graduated from college in 1935, Benny Goodman was miles above anybody else.

Manning: I read that you arranged Goodman’s famous 1939 version of “And the Angels Sing.”

Osser: I arranged the vocal part for Martha Tilton. In those days, they didn’t give any credit to the arrangers. Benny did a weekly radio show called Camel Caravan. His arranger (Jimmy Mundy) got the flu, and Benny needed a couple of new numbers every week. He happened to be up in Charlie Warren’s office. He was the head guy at Robbins Music, and the brother of Harry Warren, the great songwriter. Benny told Charlie that he needed an arranger for a couple of weeks. Charlie recommended me, so I did a few arrangements for next two Camel Caravan shows.

Johnny Mercer was a guest on the first one. He was performing with a quintet, sort of in the style of the The Modernaires. I did two arrangements for them. He was a guest again for the next show. During that week, Benny was playing at the Pennsylvania Hotel (New York City). One day, he went there for dinner after the show. Ziggy Elman, the trumpet player, had played this fast Jewish-sounding tune that he had written. Benny was sitting with Mercer, and Johnny said, “That thing that Ziggy played has a nice melody, but maybe you could slow it down a little and I could write a lyric to it.” So Benny says, “Then go ahead and do it.”

So Johnny wrote it and called it, “And the Angels Sing.” Benny called me at home and said, “I want you to meet Martha Tilton. She’s going to do the song. I need you to arrange a four-bar introduction and one chorus, and when she gets to the last note, the drums will come in and speed it up and we’ll finish it with Ziggy’s version.” That record is in the Grammy Hall of Fame now, and if I hadn’t been subbing for Mundy, he would have done the arrangement, not me.

Did you know that I was the conductor of the Miss America Pageant for 33 years? We had a 30-piece live orchestra. Bert Parks started as the host the same year I started. He did it for 25 years.

Manning: You also did some work for the Boston Pops.

Osser: I haven’t done anything for them in five or six years. I started when John Williams was the conductor. After he left, Keith Lockhart took over. He called me two or three years in a row and asked me to arrange some Irish songs for an Irish singer. I said, “Sure, but tell the singer he hasn’t got an Irish arranger.”

I’ve got one more story to tell you. When I first came to New York, I did some arrangements for the Bob Crosby band, which was playing at the New Yorker Hotel for three months. I was doing a couple of arrangements a week for them. One day, they got a call from MGM, and the person says, “We’ve got this 13-year-old singer named Judy Garland, and we want to record a couple of swing numbers for her.” They wanted to use the Bob Crosby band for the records. We didn’t know who Judy Garland was, so we weren’t sure we wanted the band to be associated with her. But we could get some good money for it, so we agreed, but we told MGM we didn’t want our name on it. So they said they would just put down, “Judy Garland with orchestra.”

They called me to do the arrangements. At that time, Benny Goodman had a hit record called “Stompin’ at the Savoy.” Somebody had written a lyric to it. And a couple of songwriters wrote a song called “Swing Mister Charlie.” Black musicians in those days referred to white musicians as Charlie. Those were the tunes that Judy wanted to record.

We had an appointment to meet Judy and her mother. I was there with the piano and we were trying to figure out the keys to sing the songs in. I heard her sing a little bit and it sounded pretty good. I settled on a key, and then I asked Judy how it felt. She looked at her mother, who told me to take it up half a tone. We tried that, and then she looked at her mother again, who said to try it again the original way. I played it through, and her mother said it was fine. The whole time, Judy never said one word. Well, the record wound up sounding so stiff. It wasn’t her style. The record came out and went nowhere.

Years later, after I got out of the service, I was working with (bandleader) Paul Whiteman, and we were doing some shows in California called the Philco Radio Hall of Fame. On one of the shows, they had Judy Garland as a guest. Of course, by that time, she was a big star. When Paul was about to introduce me to her, I asked my wife if I should remind her that I did those songs with her when she was only 13. She said, “Definitely not.”

Interview with Andrew Ackers (son of pianist Andy Ackers), conducted by Joe Manning on December 3, 2009.

Manning: The Johnny Mathis recording of “Misty” is my all-time favorite record, and one of the reasons is your father’s piano introduction. I talked to Glenn Osser, and he told me that he wrote out the entire arrangement, including the piano fills, so your father didn’t improvise it.

Ackers: I was just listening to “Misty” last night, and I enjoyed it more now than I ever have, since you brought this all to my attention. Johnny’s singing was so spectacular. He had a beautiful voice and a beautiful style. Of course, Dad would have been playing a written score. But, I loved the style of his playing it. It was so meaningful. He didn’t roll the chords. There were little subtle touches that were examples of my father’s sensitivity. And, you can hear them everywhere because of all the records he cut during those years. You can often tell that it is him.

Manning: I was playing the Heavenly album this morning, and I was listening to the tracks where your father is featured prominently, and I noticed that he really lays back on the rhythm. Maybe that’s because he played for swing orchestras in the 1940s. There’s no sense that he is just counting off the beats.

Ackers: Well, he liked jazz.

Manning: Your father studied at Yale School of Music on a scholarship. What do you think his aspirations would have been at that time? I am sure his ambition then wasn’t to become just a studio musician.

Ackers: My dad’s family was poor. All my ancestors came from Amalfi and other parts of southern Italy. Some settled on Olive Street in New Haven, right in the heart of Little Italy. My father’s father died when he was very young, so Dad never really knew him. His mother moved in with her parents, and my dad was brought up with them and his aunts and uncles. His mother worked in a sweatshop, sewing garments. She had three children, and then her daughter died, and then my father’s older brother was stricken with polio. She had to work hard to bring up the family. My Dad grew up with an admiration for the work ethic that his mother had. His mother was one of most beautiful women I have ever met. We called her Grandma Acquarulo, which was the real family name. She kept that name all her life, but Dad’s professional name was Ackers; and at one point, he had our names legally changed to Ackers.

There was music in that entire family. My father’s Uncle Frank played and taught guitar. My father’s Uncle Andrew taught music either at the high school or college level. My father’s Uncle Jimmy taught voice. They owned the house, and there was a Spinet piano on the top floor. Because the family was poor, even though my father had a scholarship to Yale, he couldn’t afford to finish up his time there.

In the early 1940s, in his last year at Yale, he was accepted into the Dorsey band, either Tommy or Jimmy, I don’t remember. When he got the telegram inviting him to join the band, he decided immediately that this is what he would do, because he wanted to help support his family, and because it was one of the most popular bands at the time, and he would be making decent money. His mother told him, “You don’t have to do that; you can finish going to school.” But, he knew the income would help her. So he went.

Dad found his calling very early in life, by way of wanting to support his family. My dad was never the kind of person who had big aspirations. He was very much in the moment. He was very practical. In those days, the Schubert Theater was big in New Haven, and there were a lot of big band venues in the city. That’s how my father met my mother. He was performing in New Haven, and my mother went to hear the band. They were married in 1942.

My father was never just a studio musician. He was a big band performer, accompanist, songwriter and recording artist. Then he did television commercials. He was where the money was, but more importantly, where the art form was going.

Manning: Did he take your mother on the road?

Ackers: No. When he went on the road, my mother had to live with her parents, who were also immigrants. She was a little annoyed by the fact that my father was away. Dad played at famous nightclubs during that era, like the Coconut Grove. Then he went into the Army and put in charge of a band, as the conductor. That’s when he met Mindy Carson, who became the singer for the band. He did recordings with her right off the bat. There are old records around with Mindy singing and my father playing piano. And he did a lot of radio broadcasts with her while in the Army.

When he was discharged, before the war ended, he went back on the road again. At that time, he would sometimes take my mom with him. The nightclub scene was very social. I am sure that she complained quite a bit whenever he was away without her. By that time, Mom and Dad had started living a pretty nice life. He was very popular and on the radio a lot. Maybe even the NBC Radio Orchestra, who I think premiered one of his compositions, “The Princess Suite.” Dad also met singer Jane Morgan, and went on the road with her. I think that’s when my mother put a stop to my father going on the road. The big band era was ending about that time anyway.

They moved to New York and lived at the Des Artiste, which was one of most beautiful buildings on Central Park West at the time. It was filled with famous people, especially artists. In 1950, they moved to Midtown East, which would be near Beekman and Sutton Place by the river. He was still working as an accompanist, and sometimes he even played in the pit in Broadway shows. They had wanted a child for a long time, but had some trouble with it. It took 10 years from the time they were married, but finally, I was born in 1953. That settled the issue of him being on the road. He wanted to stay in New York and bring up his son. This was my parents’ definitive decision.

Manning: When did your father get into doing studio recordings?

Ackers: Probably around the time that the LPs started coming out (1949). He had also been writing music, starting in the ‘40s. He had a lyricist, Ruth Poll, who was the wife of a famous doctor. She asked my dad to write music to her words. Around that time, my dad also started composing and playing for Musak. In the ‘40s and ‘50s, Chappell Music was publishing his work. Dad had a song plugger by the name of Johnny Farrow. Ella Fitzgerald sang one of my Dad’s songs, which she performed at the Philharmonic. It was called “A New Shade of Blues.” ASCAP has about 50 of his songs. Another great song he wrote is called “If You Were There.” Both of those songs had lyrics by Sunny Skylar. In the 1960s, Dad wrote many songs with him. I am a very proud Estate Member of ASCAP.

On the back of the Diamonds hit single “Little Darlin'” (doo-wop recording in 1957) is my dad’s song “Faithful and True.” It wasn’t really his style. I remember asking my father once when I was young, “Dad, which song do you think made you the most money?” He thought for a moment and then replied, “The song that made the most money was actually the flip side of a hit.” That was “Faithful and True.” I laughed at the response and remember thinking, but not saying, “As long as it made money.”

When Cecil B. DeMille was making the movie, The Ten Commandments (released in 1956), my dad was one of the last contenders for writing the score (Elmer Bernstein was chosen). He wasn’t the Hollywood type. I still have demos of the work itself. The sheet music was published as well.

Because of my dad’s profession, I didn’t see him a lot when I was young. He had record dates almost every afternoon. He would come home for dinner, which was at the same time each night, because that was the Italian tradition. Then we watched the evening news. But many times, he had record dates at night also. And, in between, he practiced quite a bit. We had a six-legged baby grand, which was such a beautiful instrument. You have never heard a tone like this. He practiced all of the classics, not pop or jazz. He did that because he needed to practice sight reading, which you had to be good at to be a valuable studio player. If you take that 10 to 15-year period in his life, when he worked in the studios afternoons and evenings, that must have come out to a lot of records.

I was an only child, but I was always treated as an adult. We would dine out once a week at a restaurant called the House of Chan. It was a very famous Chinese restaurant. We used to go on cruises every year. He was always apologizing for not being with us that often, so he would take three weeks off at Easter time, when the schools had a vacation. He loved to pick out which cruise he wanted to go on. In those days, all the major lines and piers were in Manhattan.

My mom would buy a wardrobe once a year. I got my first tuxedo and dinner jacket when I was 10. We always went on the second or third largest ship on a line. All these cruises left from the West Side of Manhattan. We would go for anywhere from seven to ten days. The first cruise we took was almost three weeks. On the fourth cruise we took, there were flowers placed in their room, and Mom and Dad were invited to sit at the captain’s table. We weren’t wealthy, but we were comfortable.

Manning: You told me you used to go to the studio when he recorded.

Ackers: Yes, I did. It was exciting. The singers were famous, and I knew it. They gave me a seat by the piano next to my dad. So I sat right there while he was playing, never in the booth. What I got out of it was a tremendous feeling of pride. Here he was with a high-powered, small but high quality orchestra. In such a short time, they would have music placed in front of them, and they would have to play it correctly right away. The accompanist is the cornerstone of the orchestra for a singer, so my dad was very important. I was also proud that he interacted with the conductor-arranger. If there were any questions about a wrong note, my dad would bring it to his attention.

I actually was in the studio more when he was playing on TV commercials. This was into the 1970’s. His TV commercial era was quite significant. When the recording industry started moving to California, my father became one of the top studio musicians for TV commercials. He was on so many of the commercials in the 1960s and early 1970s. He not only played piano, but he helped the leaders arrange as well. He was doing commercials for big companies such as the oil, cigarette and car companies. They had big advertising budgets and hired top union musicians.

The musicians were making good money, at least for musicians. And they had great singers, who were earning even more. I remember two in particular: Darlene Zito and Rosemarie Jun. Darlene had an apartment on Sutton Place, overlooking the river. Every New Year’s Eve, she would host a party, and my parents often went. I would be staying a few blocks away with a friend, but at 11:30, my parents made certain that I was called over so I could be with them at midnight. I was the only young person in a room filled with adults.

Manning: He must have had a lot of record dates where he hated the music or didn’t care for the singer. Did you ever get the sense that at times, he would have asked himself, “Why am I stuck doing this kind of stuff, when I could be doing something challenging and of higher quality?”

Ackers: But that’s the decision he made. He was an accompanist, and that’s what he wanted to be. He just loved playing and performing, but he didn’t have to be the person up front. He always liked being the person behind the scenes. I suppose that in the years when he was the accompanist for Jane Morgan, Jane Froman, Kay Armen, and people like that, or when he was a conductor in the Army, he enjoyed it. Music was my father’s passion. He was the accompanist and musical director for the Kate Smith Show back in the early TV days. In those years, he was friendly with Nat and Maria Cole. They came up to our apartment. He used to play cards with Nat and some other friends. He also played and recorded with Tony Bennett, Vic Damone, Bobby Hackett, Billy Bauer, Steve Lawrence, Eydie Gorme, Robert Goulet, Carmen McRae, and many other singers and musicians.

At one point, my father studied composition under a man named Tibor Serly. He was a great composer and teacher, and studied under Zoltán Kodály (prominent 20th century Hungarian composer). He took only a small number of distinguished students, so it was an honor for my dad to be one of Serly’s students. I was inspired by those new chords he taught at the time and still have his exercises.

With the Internet now, I am able to hear a lot of the records that my father played on. I can recognize my father’s style. Compared to my father, almost every other studio pianist was mechanical. My father had a very musical way of pacing. You think of an ocean and its waves going higher and lower, and that describes my dad’s playing. He wasn’t just playing the notes as they were written. And very importantly, he knew how to play for the singers, how to make them sound good.

There was another pianist who competed with him named Bernie Leighton. He was the only other studio pianist in those days that had the caliber of my dad. They were friends. But even Bernie didn’t play with the same feeling. In fact, I can almost always recognize my father on piano when I hear something that he played on. I remember one time when I was getting a haircut. They were playing Musak in the background. All of sudden I heard this piece I had never heard before, listened to the piano part like you did with “Misty,” and said to myself, “That’s my dad.”

Andrew Ackers is the son of the composer and pianist Andy Ackers. As a child, he was a student at the Turtle Bay Music School. He played Bach, Chopin, Mozart, Schumann and other classical composers in a number of recitals as a student pianist and composer. He has more recently begun his studies and work with composing, arranging and producing contemporary classical music, much in the aleatoric style. An Estate Member of ASCAP, he arranged and orchestrated a number of his father’s unpublished compositions.

Since young adulthood, Ackers, who resides in New York City, has devoted his life to his faith, the arts, writing, editing and music. In addition to much of his own unpublished works, he has developed musical and educational programs. One included an experimental two-year project, where as a volunteer with an Occupational Therapist, he was able to teach music and music history to young children with special needs who were non-verbal. At the conclusion of the project, all children were able to speak, and some were able to write to varying degrees.

The themes of all his work are of mostly moral context, and the purposes of his art are for praise, thanksgiving, and sharing of the gifts and very special perspectives he feels he has been blessed with throughout his life.

Interview with Johnny Mathis, conducted by Joe Manning on December 2, 2009.

Manning: Why did you record the album, Heavenly, at that time?

Mathis: I had gone through the process of finding out what kind of records I was going to make. The first album, which was called A New Sound in Popular Song, was basically a lot of jazz musicians getting together with charts and me singing every note that I could, trying to be relevant, and not really knowing what I was doing. But then I got some help from Mitch Miller, who took me in a direction that seemed to suit my voice better, with very romantic songs that I didn’t really vocalize like a jazz singer, I just sang them.

I recorded an album with (arranger) Percy Faith and some singles with (arranger) Ray Conniff. By then, I wanted to do songs that I had been listening to by iconic singers such as Sarah Vaughan and Ella Fitzgerald. That led to doing Heavenly.

Manning: How did “Misty” get chosen for the album?

Mathis: I chose it, and there were several reasons. I heard Erroll Garner play it when I was in my early teens. I was frequenting a jazz club in San Francisco called the Black Hawk. Erroll played there about three or four times a year. One night, he played the song. There were no lyrics yet. I liked it a lot. I blurted out, “Mr. Garner, I am going to record your song if I ever make a record.”

Several years later, Johnny Burke had written lyrics to it, and I had fallen in love with an album that Sarah Vaughan had made with Quincy Jones. It was called Vaughan and Violins. I just loved their interpretation of “Misty.” Erroll’s business manager, Martha Glaser, heard somehow that I was going to record it, and she showed up at the recording studio. But we had a little problem, because I was told to record a song from one of the current Broadway shows for which Columbia was planning to do the original cast recordings. That was going to push “Misty” out.

Well, that just couldn’t happen, because there sat Martha Glaser waiting for me. By the time we got to the last song, which was “Misty,” someone reminded me that I was also obligated to sing one of the Broadway show songs, and so we had a little argument over that. I said, “Let’s just do ‘Misty,’ and then sing the other song through and see which one comes out better.” When I sang “Misty,” I remember the oboe solo, and that I just sort of came in at the wrong time with that high note. Well, it turned out to be a famous moment in the song. Looking back now, it was wonderful that it happened sort of accidentally on purpose.

Manning: I heard that you stood a distance away from the microphone and walked toward it in order for the high note to fade in. Is that true?

Mathis: Absolutely. I used that device a lot back then. They couldn’t do it technically in the studio, so if you wanted it done, you had to do it yourself. What you did in those days was often very much off the cuff. Since you did the recordings entirely live, you had only one chance to sing the song. When you have to do four songs in three hours, which was what we did in those days, you really don’t have much time to do anything more than what comes natural to you. If it works, it works; if it doesn’t work, it’s still going to get released.

I copied Sarah Vaughan on “Misty.” I did that for the first 10 years of my musical career. I would find a version of a song that was done by my favorite singers, and I tried to do it the same way. At that time, I thought that was the way it should be done. I would do these little vocal things that were not natural to me, but that was the way Sarah did it, so I did it that way. Of course, now when I sing the song, I would never do that. I sing it the way I sing it. But at the time, I was madly in love with her arrangement of it.

Manning: That’s not unusual. Ray Charles started out trying to sound like Nat King Cole, before he found his own voice.

Mathis: When I listen to my music over the years, I will recognize my Billy Eckstine period, or my Ella Fitzgerald period, or my June Christy period. I was so enamored with these people, and fortunately, my voice was flexible enough so I could emulate them.

Manning: How much did you rehearse the songs on Heavenly with Osser?

Mathis: Not much at all. We got together, and I told him what songs I was going to sing and what key I was going to sing them in. I put in my two cents about how I wanted the arrangement to sound. Glenn went away and came back in one or two days, and we went into the studio and did the album. It was amazing that things got done at all. But I was very fortunate to have guidance. Fortunately, we had great arrangers and conductors like Glenn and Percy, who had agreed to work with me. All I had to do was concentrate on singing. I was in a wonderful place at Columbia. I had nothing to worry about.

Manning: Glenn told me that you did the demos of the tunes with just a guitar, so he could hear what key you were in and how you were going to vocalize the songs.

Mathis: I did that. I had the fortune of having a good musical director at that time. His name was Frank Owens. He helped me a great deal. And there was a guy by the name of Bob Prince, who was very important in my early associations with people at Columbia. Bob took me by the hand and guided me through the first four years. He introduced me to a lot of jazz musicians who had a lot of time on their hands when they were just practicing. They helped me a great deal in trying to figure out which key I was going to sing a song in. I can’t stress enough how important all these people were to me at the right time in my career. It was the only way I could ever have gone on to do the things I have done over the years.

Manning: When you did the demos with the guitar, who was the guitarist?

Mathis: It was probably either Tony Mottola or Al Caiola. Both of them worked with me later on my album Open Fire, Two Guitars. Speaking of demos, back when George Avakian signed me to record for Columbia, Vince Guaraldi, who of course became very famous later, was the guy who played on my demonstration tapes. I sent about 20 songs to George.

Manning: When you finished recording “Misty,” did Mitch Miller or anyone else in the studio think it was going to be a hit single?

Mathis: Never. It was too jazzy, and it was merely an afterthought on the album. In those days, you never would have thought that a song like that would come out of an album and become a hit. You would do singles deliberately. Some songs were to be done as singles, and others would be just for albums.

Manning: In retrospect, there are things about the song that sound like it was a potential single. It was the track that led off Side Two. It was shorter than most of the other songs, so it was radio ready. It had a catchy, easy-to-remember title. The arrangement was simpler and had a steady slow dance rhythm, and the song did not have an introductory verse like a lot of others on the album. It seems like a natural for a single now.

Mathis: That was one of the great advantages of having Glenn writing the arrangement. He composed that little melody for piano that starts it off. It was in strict time, and gave you that dance feel. I didn’t realize at the time that Glenn wrote a lot of dance music.

Manning: The echo on the piano is so haunting. It makes me feel like I am hearing the song late at night in an empty dance hall.

Mathis: I was very lucky that Columbia found that studio and that I recorded there for the first 20 years of my career.

Manning: Did you do more than one take on “Misty?”

Mathis: Probably two or three, since I needed to get that high note to come out right. Frank Laico, the engineer, worked with me on that.

Manning: You were pretty young then and hanging around a lot of important people. You must have had a lot of self-confidence.

Mathis: Not really. I had no confidence at all then. But what I did have was the ear of people such as Glenn and Percy, so I could try out things and ask them if they sounded good.

Manning: On “Misty,” you had a lot of space to sing in, which gives you more of an opportunity to stylize it.

Mathis: That’s right.

Manning: I think most people would agree that you have the definitive recording of “Misty.” Is the Sarah Vaughan version still your favorite other version?

Mathis: Maybe. I grew up listening to her and had a great number of her records. Her version of “Misty” was the only one I had heard prior to recording it myself. And I loved it not only because of her singing, but because of Quincy’s chart on it.

Manning: I assume you must have met Sarah at some point.

Mathis: I did.

Manning: Did she know you had modeled your version after hers?

Mathis: Of course.

Manning: Do you think “Misty” is the best thing you’ve ever done?

Mathis: It’s the song I am most proud of, because I did it myself. The other stuff was handled more or less by Mitch Miller, or whoever was the producer of the moment. But I took it upon myself to do the tune the way I wanted to, and to have it actually become a signature moment in my musical career was the best thing that could have ever happened. I loved Erroll Garner so much. He was a wonderful musician, a genius really, because he couldn’t read music. He never played the song the same way. He had all these amazing inventions he played before he started playing the melody. I was so proud that I had heard the tune when I was very young when there were no words to it, and that I kept my promise to record it, and I did it in a way that would last over a couple of lifetimes.

SOUND SAMPLES:

1. Piano introduction composed by Glenn Osser and played by Andy Ackers

2. Entrance of strings in the second verse

3. Mathis fade-in after the instrumental bridge

4. Strings and piano in four-bar ending