“When he (Pete Seeger) sang ‘Wimoweh,’ and he got the whole audience to sing, I had an epiphany. I knew that this is what I wanted to hear, what I wanted to know more about, and what I wanted to play.” -Mark Max, co-founding member of the Courriers

“We did a gig at the Bitter End in Greenwich Village. Bill Cosby, who was an unknown then, had just graduated from Temple University, and had moved to the Village that summer. He was doing that famous Noah routine. He won’t remember this, but he would run over and watch our show, and then we would run over and watch his show.” -Russell Kronick, co-founding member of the Courriers

It was a summer day in 1963. I had the weekend off from my job as a medical corpsman at Dover Air Force Base Hospital (Delaware). I still had three more years ahead of me before my hitch would end. I drove my ’59 VW Beatle down to my favorite sandwich shop, ordered an Italian sub with plenty of oil and vinegar, scarfed it down in the car, and listened to the radio. A song caught my attention. You could tell by the words it was called “Sing Hallelujah,” and the singing group sounded like the Weavers. It was fantastic, but the DJ didn’t identify it.

Listen to 50-second sample of “Sing Hallelujah.”

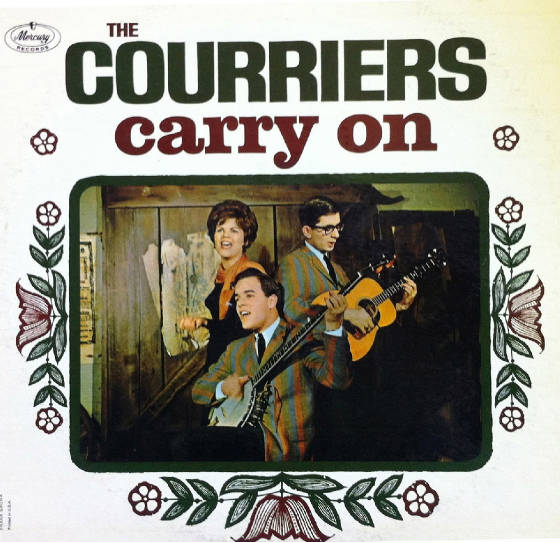

A half-hour later, I walked into a downtown record store and asked somebody about it. “Oh, yea,” he said, “that’s by a new group called the Courriers. We haven’t got the single, but I think we have a couple copies of the album.”

When I got back to my room at the barracks (it was really like a dorm), I pulled The Courriers Carry On out of the sleeve and placed it on the turntable of my $60.00 portable record player (with detachable speakers) that I had recently bought at W. T. Grant. The first track was “The Black Fly Song,” which was so fast and exciting that I picked up the stylus and played it again. The other 11 songs were great, too. I loved it. I still do.

Obsessive music lovers and record collectors like me remember the details. I heard “Hey Jude” the first time while crossing the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, Bobby Darin’s recording of “If I Were A Carpenter” at a Burger Chef in Colorado Springs, and “Sing Hallelujah” by the Courriers in the parking lot at the Roma in Dover. And nothing pleases a record hound more than owning a great album by an artist that nobody else seems to know anything about. Among your peers, it gives you bragging rights. For 50 years now, The Courriers Carry On has been one of those records for me.

In this case, I didn’t know much about the Courriers either, except that they were from Canada. Last year (2013), I finally burned the record to a CD, prompting me to look them up on the Internet. Did they do any other albums? Are they still around? I wanted to know. The back of the album cover named the members, Russell Kronick, Jean Price and Mark Max. The latter name seemed unique enough for Googling. I found one in Ottawa, Canada, and tracked down his phone number.

“Hello, I’m looking for the Mark Max who was a member of the Courriers.”

“That’s me.”

I told him how much I loved the album, that I wondered what happened to the Courriers, and that I was a writer and wanted to publish an article on my website about the group. He was a bit dumbfounded, but also flattered. Over the past few months, I have conducted long interviews with him, and his lifelong friend, co-founding member Russell Kronick. I’ve also done a lot of poking around in newspaper archives. It’s amazing how much you can dig up these days.

Mark told me right off that Jean Price left the group shortly after they cut the record, and he had lost track of her over the years. She was the second of three female singers they had during their professional recording years in the 1960s. Cayla Mirsky was the first, and Pam Fernie was the other. None were available for an interview.

It’s been fun getting to know these guys, who I have come to admire and respect for their musical abilities, the success they’ve had in their chosen careers after a short journey on the folk circuit, and for their great story telling. For readers, what emerges in the interviews is an insightful and often funny account of the daily grind of pursuing a music career, and how they faced tough decisions about when to move on with their lives, while continuing to play and create good music locally. And finally, Mark and Russell have given us colorful anecdotes about the various stars and not-quite stars of the folk music scene that they met, befriended, or performed with along the way.

Fifty years after I heard “Sing Hallelujah” for the first time, it’s nice to know that the Courriers are, indeed, still carrying on.

The following is my edited interview with Mark Max, which was conducted on August 9, 2013.

Manning: What year were you born?

Max: 1940, in Ottawa, where I’ve lived all my life, except for a few years in Toronto. My father had a ladies’ wear business here. I grew up in a very musical family. My father was a first violinist for the Ottawa Philharmonic Orchestra, for 62 years. My mother was an excellent pianist and could have been a concert pianist, but after she married my father, she didn’t actively pursue it. My father liked to be in the limelight.

When I was older, I asked my mother why she never continued her own piano studies after she married my father, and she said to me, ‘There’s only room for one star in the family.’ When I was young, we used to sit around the piano on a Sunday night. My father would play the violin, my mother would play the piano, and we would sing from the Evergreen Songbook, which included Stephen Foster songs and others like that; so to this day, I can pull a song from the back of my mind, although I can’t remember sometimes what I did yesterday.

Manning: Did you feel pressure to become a musician?

Max: No, not at all.

Manning: But, you did, anyway.

Max: I begged my father, from the time I was seven or so, to let me play the violin, but he decided in his infinite wisdom that at that age, it would be too difficult. So I took it up at the age of 10. I wound up having a sterling career, for a short time. I won the highest marks on the Ontario Conservatory of Music exam. The adjudicator told me that I was a great talent. But when I hit the point where I had to master playing vibrato, I lost interest. When I was about 13, I decided that I wanted to play the banjo. Having played the violin, I had already played a four-string instrument, and anything over four strings scared me. But I still don’t know why I chose the banjo. I wasn’t into folk music then.

That summer, I got a banjo and went to a camp north of Montreal, and I played that banjo on the train till my fingers bled, but I learned some chords, and I thought I was pretty good. The following year, I went back to camp and met a guy by the name of Stan Cassen. He was playing the guitar and singing folk songs. I had heard some folk music by that time, and saw Alan Mills in concert. When I was leaving to go home, Stan said to me: ‘I have something I’d like you to do. Are you going through Montreal?’ I said that I was because I was going to visit my grandmother there. So he told me, ‘Pete Seeger is playing there at Gesu Hall.’ So I got a ticket and went to see Pete, who was also with the Weavers then. When he sang ‘Wimoweh,’ and he got the whole audience to sing, I had an epiphany. I knew that this is what I wanted to hear, what I wanted to know more about, and what I wanted to play.

Manning: Were you aware at the time that the Weavers were controversial because of their connections with liberal causes? Several of the members had to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Max: I was not aware of that when I first saw Seeger. My epiphany at the concert provoked me to find out as much as I could about him, which, of course, led to the Weavers and more. After I started discovering his story, I found out about the Almanac Singers, his union activities, their unwavering support of liberal causes and subsequently the House Un-American Activities witch hunt.

Manning: Did you identify with that?

Max: To the extent that I am a Jew, and a minority. I wanted to be a part of the social consciousness of it. I went to Sam the Record Man, a famous record store in Toronto, and bought some records by the Weavers. I played them over and over again and started learning the songs. I was also listening to the Staples Singers, and a lot of other Gospel music. I was very attracted to that. I was 14 then. From that point, I looked for opportunities to play. I played at camps again and led sing-alongs.

We had a grand piano in our house that my mother played, my father had a violin, my brother had a mandolin, my sister had a flute and clarinet, and I had my banjo and a drum. When they were not in use, they were placed under the piano. One day, I came home from school with a double bass that I wanted to learn to play in the band. I carried it home on my hip, which was about a 10-block walk. I rang the doorbell, and my mother opened the door and said, ‘Oh, no, you’re not going to put that under the piano,’ and slammed the door in my face. She finally let me in, with the bass. That night, I started to tune it. It had big, heavy catgut strings on it, and the strings broke and left me with a big burn across the back of my hand. So I decided that I wasn’t going to play anything that was going to hurt me like that, and I took it back to school the next day.

Russell Kronick had heard some folk music, too. We were boyhood friends, and he went to camp with me. Russell’s mother told him in 1958 that she was in charge of organizing the Hanukkah ball, and she wanted him to get a group together to sing at it. At that time, Russell was singing around town, performing occasionally in a group that sounded like the Four Aces (had the hit record of “Love is a Many Splendored Thing”). He called and told me about it, and I said I would do it.

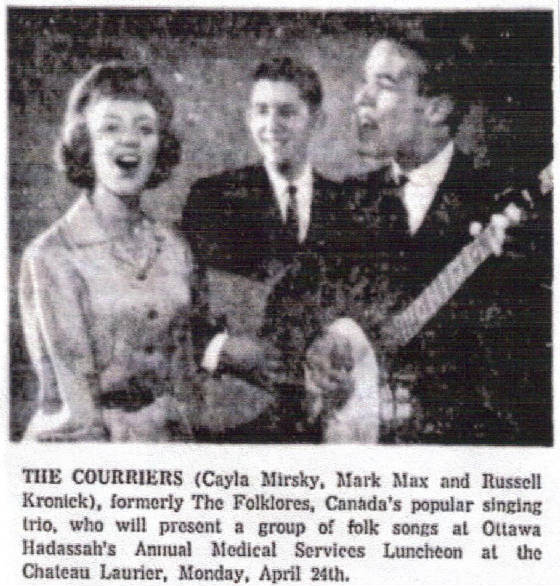

A short time later, the Kingston Trio came out with “Tom Dooley” (1958 hit). We decided that we wanted to sing in that style, so we started looking for a third member. A couple of people were recommended to us, but we didn’t know them that well. But we knew Cayla Mirsky, who was three years younger than us. She was in a camp show, and she loved to perform. She was a very vivacious performer, so we tried to get her. She agreed, but she didn’t know anything about folk music. We did our first concert. We sang “Tom Dooley,” and we did a lot of Hebrew songs, which we had been doing for a while. We were a great hit. Everybody loved us, and we started to get calls for bar mitzvahs and other things. It was getting a little crazy, and someone told us that we should join the union, because then we could charge a fee. So we did, and that ended it, because no one wanted to pay us. We might have been good, but we weren’t that good.

In 1959, a man named Alex Sherman, who knew nothing about folk music but was involved with Capitol Records, offered to manage us. He got a gig for us in Montreal at the Venus de Milo Room. We performed there with Cayla and sang folk music. Cayla wasn’t even old enough to drink. We had to watch out for her because guys were coming on to her at the bar. Alex told us that he wanted to book us at lots of nightclubs, and we weren’t comfortable with that. Our parents were even less comfortable. And Russell and I were busy going to college.

Manning: At this point, did you begin to think about becoming professional musical performers?

Max: No. We were just enjoying it. But then we got another manager, a man named Harvey Glatt. He had brought folk music acts to the area, such as the Clancy Brothers, the Weavers, and Oscar Brand. In the summer of 1961, he got us some auditions in New York through Len Rosenfeld and Marty Erlichman. After two or three visits, Harvey goes back to New York. He meets with Len, but Marty isn’t with him. So he asks where Marty is. And Len says: ‘Marty has flipped out for this little Jewish girl with a big nose from Brooklyn. He says she can sing like a bird, and he’s convinced that she is going to be the next great American singer. So we’re no longer partners, and he’s going to manage her exclusively.’

Manning: Barbra Streisand?

Max: That’s right. In fact, at the end of the last Streisand TV special that I saw a few years ago, the last credit on the screen was ‘Executive Producer, Martin Erlichman.’

In the summer of 1962, Harvey got us a record deal with Mercury Records to do our first album, and he also got us a bunch of gigs, but then Cayla’s father decided that she’s too young for this. So we needed a female singer. Harvey had heard Jean Price sing at the local TV station. We had never met her. She came over to Harvey’s house to audition for us. When she started to sing, Russell and I just sat there with our mouths open. I had visions of Joan Baez. She learned our repertoire very quickly, and we took off on the road. We took Pete Fleming with us as the bass player.

We went to the Playboy Club in New Orleans, and The Bitter End in New York. One of the other gigs was in Huntsville, Alabama, at Alabama A&M (historically black university). We were driving a 1956 Cadillac convertible which was owned by Pete. We drove up to the college and noticed that everyone was black, more than any Canadian would have ever seen. No one came to greet us, and no one said to hello. I got out of the car and wondered to myself, ‘What are we doing here?’

Then all of a sudden, somebody said, ‘You’ve got a Canadian license plate. Are you all from Canada?’ We said yes, and they started welcoming us and acting friendly. We found out that the college hadn’t sold more than 10 tickets at that point. But in the space of an hour, the place was full, and everyone in the audience was black. We did our Hebrew songs, some French-Canadian songs, and “Oh, Freedom,” and they were all very well received. In fact, we got an ovation that lasted 10 minutes. I still get chills thinking about it.

When we were at The Bitter End, we were invited to a party at some apartment on Park Avenue. As we went in, on the couch were Erik Darling, Marshall Brickman, who were playing banjos; and standing beside them was Fred Hellerman, who was playing the guitar. All of them had been members of the Weavers. If there was ever one guy who played the guitar that I thought I might be like someday, it was Hellerman. I remember seeing them do “The Saints Go Marching In,” and the place went crazy.

Also, when we were at The Bitter End, we were staying at a motel across the river in New Jersey. The guy that ran the motel heard us rehearsing, and he said to us: ‘How would you like to make your room and board? You could sing by my pool every afternoon for an hour. I’ll advertise it, and you won’t have to pay.’ So we agreed, but the problem was that suddenly we were doing the recording, we were singing at The Bitter End, and we were singing by the pool. Eventually, our voices started to get worn out. So we finally stopped singing at the pool, after about two weeks. Then the album (Carry On) came out.

However, Russell was starting law school, and I was still in school and had plans to be an accountant. So when we were asked to go out on tour and promote ourselves, we had to say no. But we continued to do some of the clubs in Toronto, like the Purple Onion. We could sell out that place in a minute. We also had some gigs at universities.

Manning: What did Mercury say when you refused to go out on tour?

Max: They weren’t thrilled, but there was nothing they could do. They released the record, but not as many copies as they would have if we had toured.

Manning: How many did they sell?

Max: I have no idea. But when we went back to Canada and worked in clubs there, we were approached by RCA. By then, Jean was no longer with us, and Pam Fernie was singing with us.

Manning: What happened to Jean?

Max: She married and just disappeared. I’ve tried many times to find her.

Manning: When you recorded Carry On, David Carroll was the producer. Did you have much say in what it was going to sound like?

Max: I think we did. Elmer Gordon was the musical director. He played piano, and he had a good feeling for our music. Carroll wasn’t familiar with folk music and leaned toward the pop stuff, so he often would say, ‘Oh, no, no, you can’t do that.’ But Elmer understood what we were trying to do. One day, we had to be at the studio at 2:00 to record. We were on time, but Elmer was late and didn’t arrive till about 2:20. He looks at us and says, ‘You never arrive on time. If you’re going to be stars, you have to arrive fashionably late.’

Manning: Were you happy with the record?

Max: We were thrilled with it. It sounded just like we wanted it to. It captured us the way we were doing it live, going 150 miles an hour.

Manning: I still marvel at how fast you were singing, and how much sound you were getting from just three singers.

Max: You mean how fast we were singing the words?

Manning: Yes, that’s what I mean. But I could still understand them.

Max: Right from the start, I thought it was very important for people to hear all the words. Otherwise, what good is it?

Manning: All your albums were very good, but I don’t think that any of them approached the intensity of Carry On. I talked to Russell about this, and he said that you might have been trying to get a little more of a pop sound, because a lot of groups were starting to do that.

Max: I think it was more that we were trying to travel down our own road. We were good entertainers, and I think we still are. We always performed with a lot of intensity on stage. We were an act. I was like Lou Gottleib of the Limeliters. I did all the talking, and Russell played the male drama queen. I was the weird guy who always introduced myself as the sex symbol of the group. I joked around a lot. I always had lead on all the wordy songs. When we had Jean, she could do the ballads well, and when we had Pam, she was great on the uptempo stuff. We all had our roles. Russell had a much better voice. My voice was more like Tom Paxton’s or Pete Seeger’s. We could do all sorts of songs. We could sound like the Everly Brothers if we wanted. My father once put Jewish words for “Bird Dog,” that song by the Everlys. We sang it at a concert we did of Jewish songs, and it was very funny.

The folk purists didn’t like us very much. But when we were at the The Bitter End, Oscar Brand came to see us. He did a lot of appearances in Canada, and had seen us there. Oscar took Russell and me out for a walk. He told us we had talent, even though weren’t pure folk singers. And he told us that Jean was phenomenal. He called her an ‘angel.’

Manning: When did you do your next album?

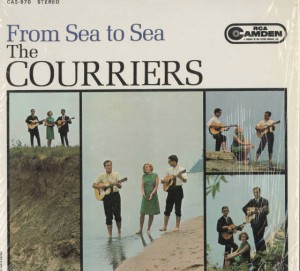

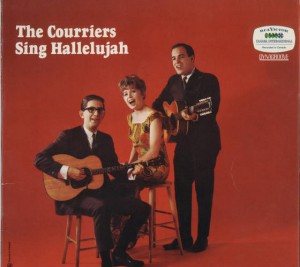

Max: We did From Sea to Sea, on RCA Camden, in 1964. And then we did Sing Hallelujah, also on RCA.

Manning: How did those albums do?

Max: I don’t remember ever getting any figures on that. We received royalties for many years, and we had our own series on CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation). I think the albums did well in Canada. We were quite well known.

“Many folk singers can be so mournful as to drive their audiences to the brink of manic depression. Not so the Courriers, a group of three extremely talented young singers who believe folk singers can tell a story without inducing sleep. They also believe folk singing can be highly entertaining to people of widely varied musical tastes.” -Montreal Gazette, August 22, 1964

Max: In 1964, we were chosen by RPM, a music magazine, for the award that later become the Juno award, the top folk group of the year in Canada. That was the year we did a summer tour out west. We had a three-week gig at the Padded Cell in Minneapolis, and on the way, Harvey booked us at the Gate of Horn in Chicago. When we came back, we made an appearance on a TV dance party show in Toronto. The MC of that show was a young man who was making quite a name for himself. He was Peter Jennings (later the ABC News anchor).

Manning: When did your careers start to wind down?

Max: When we finally wound down, we did it with a bang. In 1966, we were managing ourselves. We were getting a few odd gigs here and there. We were the first Canadian act to sign for EXPO 67, in Montreal. We were asked to go to the National Press Club in Washington, DC, to sing at a concert. Comedian Rich Little, who was also from Ottawa, was performing. We went and performed, but we did a terrible no-no. We were the opening act, and we were so well received, that we came back and did an encore. We were promptly reminded by Mr. Little, after he finished his performance, that opening acts do not do encores. Well, that bothered us for about five seconds, and that was the end of that. When we came home, I took ill and wound up in the hospital.

At the same time, the head of the Canadian Tourist Bureau called me up and told me that he wanted the Courriers to travel to the major capitals of Europe to promote EXPO 67. I told him I couldn’t go because I was in the hospital with some pretty serious health issues (which have remained with me to this very day). That was the beginning of the end. The group sort of went their separate ways. Pam Fernie went on to sing with another group, the Travelers. It wasn’t until the 1990s that Russell and I started performing again.

Manning: Did you still sing once in a while?

Max: We had our careers, but Russell and I still sang together once in a while, but we didn’t perform. I had joined my father’s business in 1963. I was very interested in advertising and promotion. One day, I went over to the National Arts Centre in Ottawa, which had been built in 1967. It’s like the Kennedy Center is to Washington. I met the personnel director there, and he got me got me to write a formal letter about why I was interested in working there. About two years later, I was invited to interview for a job. I was hired in 1972, to be the public relations person for a new opera festival they were starting called Festival Canada. When I was done with that, I was hired as the first manager of advertising and promotion of the National Arts Centre. I stayed there for four years, and then I left and formed my own agency. I did that kind of work until I retired a couple of years ago.

Manning: How many children do you have?

Max: Two. Both of them are singers and musicians.

Manning: You must have met a lot of well-known performers during your travels with the Courriers.

Max: Yes, but we didn’t get to know most of them very well, except for (singer) Josh White Jr. He performed in Ottawa a number of times. We became friends with him. One of the times we went to New York for an audition (1961), he invited us on a Saturday afternoon to go his place in Harlem. Cayla was still performing with us then, but she didn’t go with us. He gave us directions, and we took the subway. It turned out to be one of most unbelievable afternoons I‘ve ever spent. He lived in a big tenement house. Two of his sisters were there. One of them looked like Mahalia Jackson, and it turned out later that she sang like her, too. One of the sisters had a small child, and in no time, he was sitting on my lap. At one point, he ran his fingers through my hair and said, ‘Hey, man, you got funny hair.’ The whole family was on the floor laughing.

Suddenly, they started playing music, and the sister that looked like Mahalia Jackson began to sing gospel songs. Pretty soon, people from some of the other apartments came down and gathered around and joined in on the choruses. At that point, I was thinking that if there is reincarnation, I wanted to come back as a black singer in a gospel choir. When we left, we had to take a cab. Josh had two German shepherds. He told Russell and me to walk by the dogs, and he gave us a knife. He said, ‘Let’s go get a cab. I don’t think anything will happen, but if it does, use the knife.’ We’re two little white Jewish boys from Canada. We’ll nothing bad happened, but we never forgot it.

We were frustrated that the EXPO 67 died. But I don’t know where it would have taken us. In Ottawa, we are still regarded as local yokels that did well, but no one really knows how well. I was very satisfied with what we had done. I knew what we were capable of. When we started up again in the 1990s, and did some concerts here, we knew we wouldn’t be the greatest thing, but we could still put on a good evening of music.

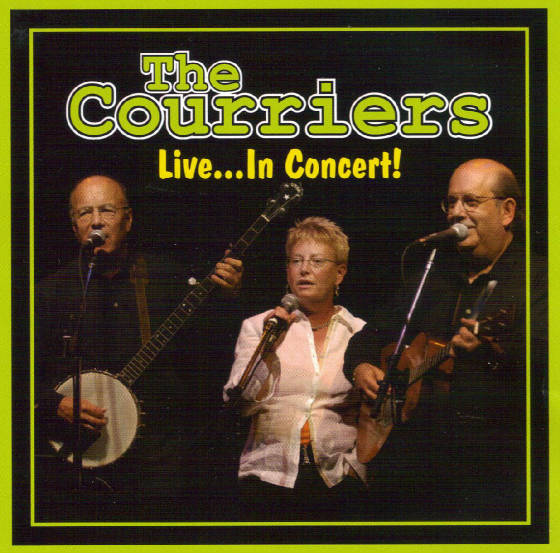

Manning: When you did that live reunion concert in 2005, the one you recorded on a CD, what was it like to go on stage and do it?

Max: It was very exciting. We hadn’t performed for so long. I was playing with my son, who was playing bass in the group, and a keyboard player who was Russell’s cousin. We had a lot of gaps in our voices, and they were filling in the gaps very well. We actually have two more recordings in the can, and Russell is looking at them right now to see if we should release them. I’ll bet that just about every Jewish person in Ottawa has that concert CD in their car. It’s been that way for years. There’s not a week that goes by that I don’t meet someone beyond my circle of friends that has the CD. I harbor no illusions that we are going to be stars again — not that we ever were, but it’s still very gratifying. I love the music, I love to sing, and I still like to perform.

Manning: I noticed that on the live album, somewhere in the middle of it, everything seemed to click. There was some kind of turning point where everyone turned it up a notch.

Max: When we started, we were nervous. After a few songs, there was one we sang that the audience was singing along with.

Manning: I think it was “All My Life’s A Circle,” the Harry Chapin tune.

Max: Right.

Manning: When you sent me all of your CDs, I listened to them in order of first and last. When I put on the live album, I was excited about hearing what you sounded like 43 years after you recorded Carry On. At first, it was sort of a curiosity, but when you sang “All My Life’s A Circle,” I found myself getting very moved by it. The lyrics seemed to bring out the emotional significance of what you were doing. It sounded like you were having a wonderful time.

Max: So was the audience. We could tell. When we got them to sing along, I got chills. They got out their lighters and lit them like they do in rock concerts.

A few months ago, my wife Yanda, my son Josh, and I drove to New Jersey to visit my daughter Nomi and her husband, so we could see my grandsons, Zachary and Rafi, perform in their band concerts and recitals. From his iPhone, Josh loaded up the car with our traveling music. He has thousands of songs, so many in fact, that he has categorized them. One of those categories is ‘folk,’ of course; he has 273 songs in that classification. Included were songs sung by the Weavers, Peter, Paul and Mary, Chad Mitchell, Bruce Springsteen, Tom Paxton, just to name a few, and, of course, the Courriers. The songs played at random, and so we sometimes heard more than one version of the same song on the 7-hour trip. And I have to say, in all modesty, that our versions measured up pretty damn well. I felt proud.

The following is my edited interview with Russell Kronick, which was conducted on March 20, 2013.

Manning: I bought your first album, Carry On, in 1963. I still play it from time to time. I was searching on the Internet recently to see if there was a CD reissue, and there wasn’t, but I found the LP on Ebay. The minimum bid was $64.00.

Kronick: Really? You’ve got be to be kidding.

Manning: I was pretty surprised myself. How long has it been out of print?

Kronick: I am guessing, but I don’t think there would have been any printing of that album after 1970.

Manning: It was issued on Mercury Records. How many did they sell?

Kronick: I have no idea.

Manning: Did you get any royalties?

Kronick: Not from that one. I did get some royalties from a couple of songs that I wrote on the second album. I wrote the songs ‘From Sea to Sea,’ and “Cherry Bough Tree.” I used to get about $2.80 a quarter. One quarter, I got a check for eight bucks. I was in a restaurant in Toronto, and I ran into a friend of mine, and he asked me, ‘Did you happen to get an extra large royalty check last time?’ And I said, ‘Why do you ask?’ And he said, ‘Well, I got a summer job as a radio DJ up in the Northwest Territory. I used to play “From Sea to Sea” a lot, and everyone loved it.’

Manning: When did you start singing and playing the guitar?

Kronick: I started playing the guitar when the group was formed, me and Mark Max and Cayla Mirsky. I’d taken some piano lessons when I was about 10 years old and discovered that I had a musical ear. When I was about 15, I taught myself to play the piano. The group started in the autumn of 1958. My mother was a musician, and she was putting together a show in our synagogue for Hanukah that December. She wanted us to sing a few songs in the show. At that point, we had sung some songs together at camp. That’s all. Mark and I liked the Weavers, which had come back into vogue in 1957 with their album called Return to Carnegie Hall. That was after the group had been blacklisted by the House Un-American Activities Committee. So I picked up a guitar and taught myself three chords, and away we went. We started out calling ourselves the Folklores. That’s was when Cayla was singing with us. But we thought the name was too specific, and we became the Courriers.

“Three young Ottawans, Cayla Merski, Mark Max and Russell Kronick, during their high school days attracted a lot of local attention with their interpretations of folk songs. About a year and a half ago the trio appeared at one of the big Coliseum Campus Hops as the Folklores. The group recently changed their name to the Courriers and cut their first disc.” -Ottawa Citizen, August 11, 1961

Manning: When I first heard Carry On, I noticed that you sounded like the Weavers.

Kronick: Well, we were strongly influenced by them.

Manning: Both musically and politically?

Kronick: Not politically. We were in our late teens. I was in my first year at the University of Ottawa. We didn’t have any political affiliation. We were just singing music that we had heard on a record. It was easy to play, and people seemed to like singing along to it, particularly at camp. We actually started singing and rehearsing about a month before the Kingston Trio released “Tom Dooley.” They and other groups went off in sort of a modern folk genre, and really angered a lot of the so-called purists. We started out on the purist side of things, but as we continued singing, we kind of straddled the line, although I’m not sure we were thinking about it then.

Manning: I think that you and Mark, when you were harmonizing, sounded like the two lead singers for the Kingston Trio. And just like them, there was a banjo and a guitar.

Kronick: Right.

Manning: When were you born?

Kronick: 1940, in Ottawa, where I have lived all my life, except when I went to law school in Toronto, and then practiced law in Toronto after I got married. My wife and I moved back to Ottawa several years after that.

Manning: When you started playing with Mark and Cayla, were you hoping to become recording artists?

Kronick: I guess so, at some point. We became quite popular in Ottawa, and then a manager picked us up. I was going to the University of Ottawa at the time. I think it was in 1959 that Mark and I quit the university and the Courriers went out on the road. We went to New York City, and we were introduced to Albert Grossman, who eventually signed Peter, Paul and Mary. He was looking for a group that had a female and two males. But we really weren’t that good, to be honest.

Manning: Were you living in New York?

Kronick: No. We were still living in Ottawa. We drove down to audition for Grossman, and then we did some gigs around Ottawa. Sometime in 1961, Mark and I committed to it full time. We were doing gigs in Montreal. Cayla was only about 16 or 17 then. Her father came to see us at a place on St. Catherine Street. It was a seedy bar that the McGill students had found and turned into kind of a folk place. He was very upset to see his young daughter working at that kind of a place, so he pulled her from the group. That’s when Jean Price joined us.

Manning: Had you known Jean for a while?

Kronick: No. The group had done some shows at CJOH, a TV station in Ottawa. Our staff announcer was Peter Jennings, the man who later was the evening news anchor on ABC. Jean was working at CJOH, and I think Peter got us together.

Manning: What was your first record?

Kronick: We did a 45 single of the song “I Never Will Marry.”

Manning: What label?

Kronick: I don’t remember.

Manning: Did you have an agent then?

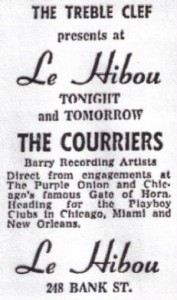

Kronick: Yes, Harvey Glatt. Our first agent was a guy who owned a record store, Alex Sherman. He was an older man and not an up-to-date, hip sort of guy. Harvey was a young entrepreneur who owned a record store called Treble Clef Records. We knew him, because we had grown up in the same community. He was our manager, the one who got us to New York, and then got us some tours around the US. It was through him that we did the 45. Cayla sang lead on the song.

Manning: How did it do?

Kronick: It got played some.

“The Courriers, three young Canadians, make their American record debut with the album Carry On, singing folks songs from around the world, ranging from the lusty to the gentle, the whimsical to the wistful. Their folk songs include those of the French Canadians, the English, the Scots, the Israeli, the Anglo-Canadians, and the American Negro. They vary their musical textures as the emotional content of the songs dictate, and demonstrate a special talent for dramatic buildup to a stunning climax. Directed by David Carroll, the songs of the Courriers are delivered like special musical messages, fresh, timely and unforgettable.” -Petersburg (Va.) Progress, April 22, 1963

Kronick: The next record was the album Carry On. We recorded it in 1962, and it was released later that year. That was also through Harvey. That fall, I was back at the University of Toronto. Harvey had put us in touch with an agent, a guy named Mason Bliss. At that point, we were having some success. We did a tour of universities in the southern US in May and June. In July, we did a gig at the Bitter End in Greenwich Village. Bill Cosby, who was an unknown then, had just graduated from Temple University, and had moved to the Village that summer. He was doing that famous Noah routine. He won’t remember this, but he would run over and watch our show, and then we would run over and watch his show.

After that, we recorded the album, and then did a tour, starting in Minneapolis, and ending at the Gate of Horn in Chicago. We were scheduled to go to the Blue Angel in New York. There was even talk about doing the Ed Sullivan Show. But by that time, I had decided to go back to the university and go to law school. I wasn’t prepared to commit myself to the life of a professional musician. So that ended the tour.

Manning: Did that kill the album?

Kronick: No. We had a large following in Canada. The album was selling. We did a short tour in the north part of the US. I recall gigs in Massachusetts and northern New York State. I would go to law school during the week, and then we would go on the road on weekends.

Manning: When you were touring, were you the top-billed act, or did you open for someone else?

Kronick: We were the only act, and we would do a full concert.

Manning: Did you ever do concerts with other performers on the bill?

Kronick: We did a hootenanny-type concert at Massey Hall in Toronto when I was still in law school. Gordon Lightfoot opened the show.

Manning: Was he well known already?

Kronick: No. He was just starting. We played a coffee house in Toronto that later became quite legendary. It was called the Purple Onion. It was the “in” coffee house in Toronto in those days. It was in an area called Yorkville Village, which was sort of like Greenwich Village. My law school (University of Toronto) was only three blocks away. Lightfoot was playing at a coffee house right around the corner from the Purple Onion. It was called the Riverboat. We had some very successful appearances at the Onion. We had become one of the emerging stars of the folk scene in Canada. So when we did this hootenanny thing, we were better known than Lightfoot.

Manning: Do you feel that because of your cultural background, you didn’t fit in with the emerging leftist political folk crowd?

Kronick: That’s a fair question. Yes, we probably didn’t fit in. But my mother was very encouraging and wanted me to continue with music. However, my father wanted me to earn a living.

Manning: Most people would say that the two are incompatible.

Kronick: That’s right. I felt that living a life as a musician was tenuous at best, and I guess I was culturally and behaviorally not cut out for that scene. I was participating in it from a purely musical point of view, rather than politics and social comment. But my mother was still encouraging me to stay in it, so in order to satisfy my father, I applied to the law school I was sure I wouldn’t able to get into, the University of Toronto. I didn’t apply to any others. In late June of 1962, we were doing a concert in Knoxville, Tennessee. I had taken a shower, and while I still had a towel wrapped around my waist, I called home. My aunt answered the phone and starting screaming to my father that I was on the phone. He grabbed the phone and told me that I had been accepted into law school. I dropped the phone on my toe, and it started bleeding.

Manning: Did you consider it good news?

Kronick: I don’t know. For a young guy out on the road singing and stuff, it may not have been good news, but at that point, I guess I had committed myself to pursuing a career in law. I had seen behavior in the Village that was really foreign to me. There was a kind of craziness to the lifestyle. I just didn’t feel that I was cut out for it. I knew that it wasn’t conducive to good family living, and I came from a strong family.

Manning: According to the album notes, the musical director for Carry On was David Carroll. What did he do?

Kronick: He organized the session. One of his roles was listening to the songs and telling us whether they were good enough for the record. He may have changed a couple of things, but that was about it. We did the songs the exact same way we did them on stage.

Manning: The first song I heard on the album – I heard it on the radio – was “Sing Hallelujah,” and that convinced me to buy the album. At one point in the song, it spotlighted Jean’s voice, and I loved it. But “Black Fly” later became my favorite track. I kept wondering how anyone could sing that fast. Who was singing lead on that one?

Kronick: Mark.

Manning: His voice sounded very boyish, but not a whole lot different than a lot of young male folk singers at that time.

Kronick: We did sing fast, probably for a couple of reasons. We were nervous, and it was also our youthful exuberance. I think if I were doing the same album today, we wouldn’t sing so fast.

Manning: When I listened to it a couple of days ago, which was the first time I had heard it in a few years, I noticed it sounded kind of dated. After all, it was made 51 years ago. And the pace of it just wore me out, which I mean in a good way. There were a couple of slow tunes, but most of the time the excitement in your vocal arrangements was relentless. You must have been awfully well rehearsed.

Kronick: I think we learned how to rehearse well. I saw this TV documentary about the Eagles recently, and they rehearsed a cappella for hours at a time. We took our rehearsals seriously. I acted as the musical director, and the arrangements were essentially mine.

Manning: Did you work out the harmonic intervals on the piano?

Kronick: Yes. And I tried to build a song toward the last chorus, which often included contrapuntal singing. I joke that I was the arranger, and Mark was the sex symbol.

Manning: What was your second album?

Kronick: It was From Sea to Sea. I was in my second year of law school. Our female singer then was Pam Fernie. Jean Price did only Carry On.

Manning: I listened to From Sea to Sea yesterday, and I detected a drop off in the intensity level. The songs were more mellow. Had you changed your style since Carry On?

Kronick: Not consciously. I think we were more mature musically. It was a musical progression from a simpler time. I knew more about harmony and arranging.

Manning: The album was on RCA. The producer was Wilf Gillmeister. Who was he?

Kronick: He worked for RCA Records in Canada. We did it at the RCA studio on Jarvis Street, in Toronto. At that time, RCA was excited about a new sound board they had bought from a bankrupt studio in Nashville. It was a 16-track recorder, and they had paid $2.5 million for it. At that time, ‘From Sea to Sea,’ which I wrote, was the song we were best known for. We were doing a lot of concerts at universities in Canada. In 1964, we were given an award as Canada’s best folk group, by a magazine called RPM. That award later became known as the Juno Award.

Manning: Was the album released in the US?

Kronick: I don’t think so.

Manning: How did it do?

Kronick: Reasonably well.

Manning: Did you do a tour for it?

Kronick: No.

Manning: Was that the end of your touring?

Kronick: No. We continued. We did coffee houses and colleges from time to time. I graduated from law school in 1965. We did a series of 13 TV shows for the CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation), which we recorded over the summer. It was exclusively our show. We had guests, but I don’t remember who now. They were mostly young performers, and I don’t think any of them became famous. When Mark became ill in 1966, we had already signed a commitment to do some more shows for the CBC. I wound up doing them myself as a solo performer.

Manning: Did you talk, or did you just sing?

Kronick: We talked and introduced acts, that sort of thing. I got married in July (still 1965). We went to the Maritimes for our honeymoon, and then continued doing the show. But just after Labor Day, I stated articling. That’s when you’re hired as a student by a law firm, and you spend a year as an apprentice. That was hard work, so I had to put off doing any singing. When I finished in the summer of 1966, we were still very popular, so we did concerts when we could.

The last show we did during that era was at Ottawa’s most famous coffee house, Le Hibou, which is French for owl. That was the Labor Day weekend of 1966. We were at the height of our popularity, and we had a tremendous crowd. But on that weekend, Mark became ill. On Sunday night, we were doing an encore song called, “Children, Go Where I Send Thee,”‘ and I looked over at Mark, who was sitting on a stool, and he looked white. We had to help him off the stage, and he was taken to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis.

Manning: When did you do the next album, Sing Hallelujah?

Kronick: We did that in 1965. Pam Fernie sang on that, too. And the guitar/accompanist was Jim Pirie, who went on to have a career in jazz and as a session player. I want to tell a story about Pam.

Manning: Let me stop for just a moment and ask you why Jean quit?

Kronick: She left the group because I started law school, and we didn’t do that tour that would have ended up at the Blue Angel. She realized that my commitment to a music career wasn’t there. She wanted to continue to pursue it, so she left the group. She ended up marrying a cameraman at CJOH, by the name of Andre Mougeot. I totally lost track of her. Remarkably, over the years, I have never been in touch with her again.

Jean had an extraordinary voice. If you listen to the folk groups of that era who had female singers, such as Peter, Paul and Mary, I defy you to name a female singer who was the equal of Jean Price. The song I loved the most on Carry On was “Wild Mountain Thyme.” Jean shows her musical and emotional range on that one better than on anything we ever recorded.

Sample from “Wild Mountain Thyme

So let me finish my story about Pam. She was working at a television station in Toronto, just like Jean had been doing when we met her. We were scheduled to drive up together to Ottawa to do our first rehearsal. We were waiting for her at the TV station. All of a sudden, the door flew open and somebody ran into the reception office and announced that (John) Kennedy had been shot. So it’s easy to remember that November 22, 1963, was the date of our first rehearsal with Pam.

Manning: On Sing Hallelujah, there was a bigger band on the record. There was an electric guitar, for instance. You recorded the song “Sing Hallelujah” again, which had been on the first album, and it had essentially the same arrangement, but with more instruments. That was also on RCA.

Kronick: We had gone from being like the Weavers, who had a guitar, bass and a five-string banjo, to being more like Peter, Paul and Mary. The folk genre had gone from its rather simplistic roots where you’re just telling a story, to a more elaborate commercial sound. Singers and producers wanted to expand their market. We were going through that process.

Manning: How did that album do?

Kronick: It did well within its Canadian market, but by the time it was out, we were on the last legs of our trajectory. And then we kind of disappeared from the scene.

Manning: The folk movement was dying at that point. You had the Beatles, and Bob Dylan had gone electric.

Kronick: Looking back, I think that justified the decision I made to choose a career in law, not music. I never thought that I was talented enough or skilled enough to cross from the folk field into some other musical genre. I made the right decision.

Manning: You’re lucky. You could have wound up an old folkie who couldn’t find any work.

Kronick: I still see people who were part of the folk scene in Canada back then, and they seem to look with a bit of envy on the choice that I made. Some of them have not ended up well.

Manning: So now we have this quiet period from 1966 to 2006, when you did the reunion album, called The Courriers, Live…In Concert! Was it self-produced?

Kronick: Yes, I produced it.

Manning: In the liner notes, it said that the Courriers had reunited in 1998. Did you and Mark perform together during that long period from 1966 to 1998?

Kronick: We sang in the synagogue choir.

I just remembered a story I wanted to tell you. Back in 1960s, we did this concert at Massey Hall. I already told you about it, and what a famous venue it was. When I told my mother we were singing there, she teased me and said, ‘Well, when you sing for the Queen, I’ll be impressed.’

When I was doing the shows on CBC, I wrote a song about the birth of Canada. In 1967, Canada celebrated its centennial. The producer of my TV show, Bill Glenn, was producing a centennial show for the Queen. The local producer for the show, a woman named Audrey Jordan, suggested to Bill that my song would be great for the show for the Queen. I called Bill and sang the song on the phone, and he loved it, and suggested having a lot of young people from all across Canada coming and singing the song. I said to him, ‘Bill, you can have the song, and you can let all these young people sing the choruses, but I want to sing the verses.’ He replied that I was kind of old, I was losing my hair, and I was a lawyer, so he didn’t like the idea. So I more or less told him, ‘If you want the song, you get me, too.’ So he agreed. So I told my mother, ‘Guess what, I’m singing for the Queen.’ And that turned out to be my last performance until 1998.

Manning: Did you meet the Queen?

Kronick: I sure did. Of course, the Duke of Edinburgh accompanied her. I watched him when I was standing backstage, and he was sitting back in his seat looking rather sedate. The only time that his interest was noticeable was when a group of Yugoslavian female gymnasts wearing tights were bouncing balls. He leaned a little forward in his seat and watched with a certain amount of glee. When the Queen came around to see us, he was one or two people behind her. She came up to me, and I bowed a little and said something like, “Thank you Ma’am.” And she asked me, “What do you do?” And I said, “I’m a lawyer.” She looked at me for a second, and then turned to the Duke and said, “He’s a lawyer.” And then they moved on.

Manning: Why did you do the reunion concert in 1998?

Kronick: We thought it would be fun. That’s all. It was a fundraiser, and someone suggested we do it. There were a number of other acts on the bill.

Manning: Who was the female singer?

Kronick: Anne Steinberg. We had been singing with her in our synagogue choir.

Manning: Why did you do the live reunion album in 2005?

Kronick: A group of older Ottawans, called AJA Plus, did programs. A friend of mine, Sol Gunner, who is a musician, suggested we do a concert and raise money for their group. So we did it at the Library and Archives theatre, which seats about 400. It was on June 22, 2005. We recorded it.

Manning: Were you the only act?

Kronick: Yes.

Manning: The album seems to indicate that you did a short set, a little less than an hour.

Kronick: We played from 8:00 to 9:00, took a 20-minute break, and sang till about 10:15. We did over 20 songs. But we edited it down to about half the show for the album.

Manning: On the album, there were only two songs that had appeared your first three albums. Were you trying to update your repertoire?

Kronick: I had gone back to playing the piano. I decided to study it at the ripe old age of 53. I even passed the Grade Eight Royal Conservatory examination in Toronto. I had expanded my musical tastes. I loved classical music, which I still study and play. I wanted to move on from the Weavers, so I think the choice of songs for this reincarnation of the Courriers was an attempt to be more sophisticated, if I can use that term.

Manning: I thought the album was quite moving. I listened to all of your albums in chronological order, the last being the reunion album. I enjoyed the first few tracks. They were fun to listen to, but I really started getting into it when you sang ‘Hallelujah,’ the Leonard Cohen song.

Kronick: I think you really put your finger on it. We hadn’t performed in many years, and to be honest, I was terrified. This is a cliché, but it’s like riding a bike. Once you learn it, you know it forever. I realized, as we worked our way through the first half of the show, that I still knew how to do it. As we went further and further into it, we got better and better.

Manning: The way the album is sequenced, you picked the best songs for the second half. Not necessarily the best songs, but the best ones for this type of event. You did a great version of “All My Life’s a Circle,” the Harry Chapin song, and followed it up with “San Francisco Bay Blues,” which was a hoot. I thought to myself, “Here’s this group I heard 50 years ago, and they’re still singing, and they still sound good.” It was nice that you had that opportunity. That’s what moved me about it.

Kronick: And we weren’t doing it for the sake of the development of a career, or to sell records, but for the true love of doing it. Our lives are what they are. We have our families and our careers, so it wasn’t going to change anything. I felt that what came through in that concert was that we were having fun. We weren’t singing complex and intricate harmonies. Many people told us after — as much as three or four months after —that they had enjoyed it very much. So we did two more of them, one a year later, which we recorded for the concert album, and the last in 2010. For all three events, we gave all of the proceeds to various charities. We haven’t performed since then.

Manning: Do you ever get together informally and sing?

Kronick: No. To be honest, now that I had the opportunity to go back and do it again, I think I’ve had it. Putting together a concert of 20 or so songs is really hard.

Manning: Do you still write songs?

Kronick: No.

Manning: Do you still listen to folk music?

Kronick: No, I listen to classical music.

Manning: How many children do you have?

Kronick: Three sons.

Manning: Are any of them musicians?

Kronick: No, not a one, but they all love music. My middle son is a producer for HBO.

Manning: Have they ever listened to your albums?

Kronick: Sure. As a matter of fact, they play them at parties. All of them have the reunion concert album. My son Michael has three children, and he won’t travel any great distance with his kids in the car without playing our albums. My son Jordan was recently married in Las Vegas, and he had about 150 young friends at the reception. It happened that my 70th birthday was the next day. Just after midnight, they surprised me by bringing out a birthday cake and playing the record of me singing lead on “The City of New Orleans,” from the concert album. Everyone sang along.

“Folk Music USA will be the convocation at Indiana State College in Fisher Auditorium, Friday, June 29, 1962, at 10:30 a.m. Featured performer will be Helen Dunlop as singer of folk songs. Along with Miss Dunlop will be the Courriers. Making a tremendous hit in all mediums, the Courriers, Russell Kronick, guitar and five string banjo, Mark Max tenor guitar and tenor banjo, and Jean Price, a three octave voice, have made a name for themselves in Canada and now are venturing forth in their first concert tour of colleges and universities in the United States. Making numerous concert appearances for colleges and universities throughout Canada, they have found themselves also popular in making seven Canadian CBC network shows in which they specialized in children’s programs. They recently had a hit in Canada called ‘Joe Bean,’ which was in the top 10. In addition, they had a one-hour special with the well-known folk singer, Pete Seeger.” -Indiana Evening Gazette, June 27, 1962

Manning: I found quite a few old articles about the Courriers on some newspaper archive websites, and I would like to get some comments from you about them. On June 27, 1962, there was a story about your upcoming concert at Indiana State College. It said that you had a hit in Canada called ‘Joe Bean.’ It was in the top 10. I just found out that Johnny Cash recorded that song.

Kronick: I think “Joe Bean” was the B side of “I Never Will Marry,” our only single as far as I know. All I remember is that Joe Bean gets hanged at the end of the song.

“About 2,000 persons are expected to attend a concert at the State University College at Potsdam Friday. Weather permitting, the Junior Mance Trio, a jazz instrumental group, and the Courriers, popular folk singing group, will perform on the college baseball field at 8:00 p.m. The public is invited if the concert is outdoors. In case of inclement weather, the concert will take place in Merritt Hall, the college gymnasium, and attendance will be restricted to students at the State college.” -Syracuse Post-Standard, September 18, 1964

Manning: Here’s another one, from September 1964. It’s about an upcoming concert at the State University of New York at Potsdam. You were on the bill with Junior Mance, a very popular jazz pianist. That was a strange combination. It was scheduled to take place at the college baseball field, but they planned to move it to the theater if it rained. Did it rain?

Kronick: I think it did, because I don’t remember ever singing on a baseball field. I do remember singing on a hill at the Royal Military College in Kingston (Ontario). It was in June, and in Canada at that time, you get a lot of mosquitoes and black flies, and they bothered us.

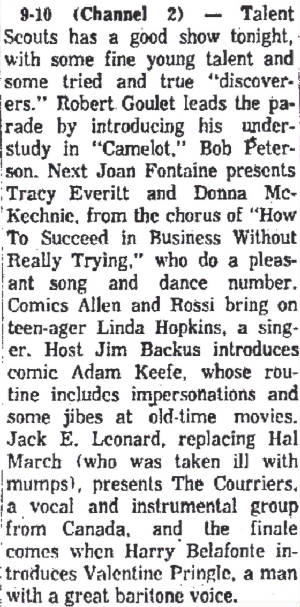

Manning: Here’s one more, on August 28, 1962. It says you’re on the TV show called Talent Scouts, along with singers Robert Goulet and Harry Belafonte, comedian Jack E. Leonard, and actor and game show host Hal March. They introduced the acts.

Kronick: I remember that. I met all those people.

Manning: Was that a thrill?

Kronick: It must have been, but I don’t remember now. It’s funny, but a couple of weeks later, I started law school. Sometimes I wonder what would have happened if I had not gone to law school, and I had stayed in music. My life was totally altered by my decision to take a different path. I’ve practiced law, and I’m a specialist in civil litigation. I have appeared in all the courts in Canada, including the Supreme Court of Canada. I’ve had a pretty good career as a trial lawyer. I have a great family. I’ve been married to the same woman for more than 45 years. I’ve participated in the community as a member of a hospital board and the district health council. I’ve had a life that is totally different from the life I would have led if I had continued to be a professional musician. And to have this opportunity to talk to you now, and to be able to reminisce about the details of my earlier life, has been fascinating.

Samples of five songs from The Courriers Carry On

Sing Hallelujah (full version)

The Black Fly Song

Vayiven Uziahu

Baby Where You Been So Long

She’s Like A Swallow

Samples of two songs from From Sea To Sea

From Sea To Sea

Cherry Bough Tree

Samples of Two Songs from Live In Concert

All My Life’s A Circle

Kretchma (full version)

On January 27, 2014, several weeks before I posted this story, Pete Seeger passed away at the age of 94. I asked Mark Max to share his thoughts about it.

“When I heard the announcement of his death, it made me stop and think a few minutes. He is, and was, my single and total inspiration for my interest in, and love for folk music. I saw him here in Ottawa in 2008, when he came with his grandson, Tao Rodriguez-Seeger, and singer-musician Guy Davis, to do a benefit concert for the Ottawa Folk Festival. It was in the same hall where we did our reunion concert and album. He was about 90 years old then. He got up on the stage with his grandson to perform. Tao was so respectful and kind and gentle while he talked softly to Pete and explained what he wanted to do. It was clear that Pete had slowed up a lot. They sang a song together, and then Pete took his banjo and pranced across the front of the stage and out into the audience singing ‘Abiyoyo.’ It was a truly remarkable sight and constitutes a wonderful last memory.”