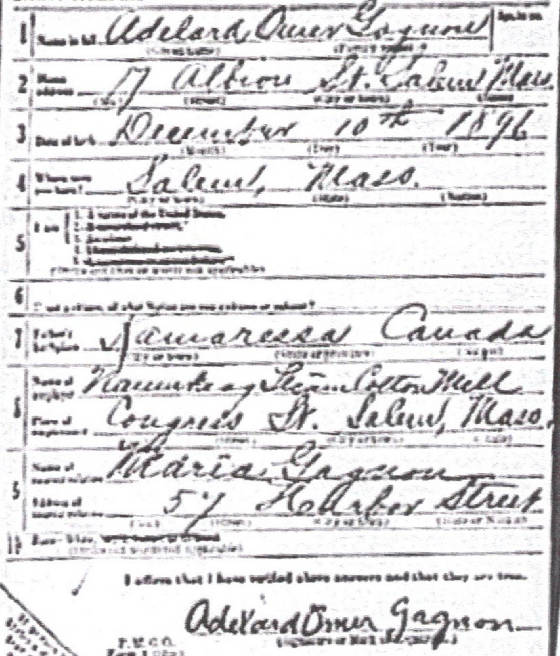

Lewis Hine caption: Adelard Gagnon (smallest), 32 Palmer St, Location: Salem, Massachusetts, October 1911.

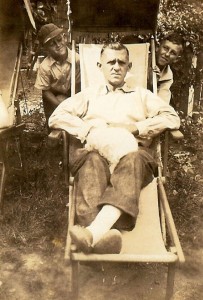

“The neighborhood kids all came to visit my grandfather, and he would give them lollipops. He never had a driver’s license, so my father did his grocery shopping for him, including looking for sales on lollipops.” -Ron Gagnon, grandson of Adelard Gagnon

**************************

“From every housetop and elevation in Boston last night crowds watched the conflagration in Salem. High windows in the business section were eagerly occupied by men and women who crowded in and begged the janitors and caretakers to give them a chance to see the flames and the reflection in the sky.”

“In Barristers Hall, the Ames building and the federal building, and on the top of all the hotels, crowds followed crowds to obtain a view. In all the places of amusement, on the corners, in the hotel lobbies the fire was the only topic of conversation.”

“Never since the Chelsea disaster have the minds of people in Boston and the immediate cities and towns been focused on one place as all were last night on the Witch City, the city of Hawthorne and innumerable traditions.”

“At the first report of the fire in the afternoon there was a disposition to treat the subject lightly. But toward 5 o’clock, when the fire engines from the outskirts began covering in for the engines which went to Salem, the excitement began to gather strength.”

“In the afternoon, from the high buildings, Salem seemed to be enveloped in a cloud of smoke through which now and then came a volume of deeper smoke.”

“Cars and trains about 6 o’clock became loaded with crowds bound for Salem. The commuters who feared that the Boston & Maine tracks would be blocked went prepared to trolley around by way of Malden or Wakefield to reach the towns to the north.”

“As soon as the Boston & Maine railroad found that tracks were threatened, preparations were made to run the Salem trains by Wakefield Junction and then around to the farther side of the city, which it was believed last night would not be reached by the flames.”

“Toward evening there was a general scamper for trolleys and taxicabs and all sorts of conveyances, and hundreds of persons went hurrying toward Salem.” –Lowell Sun, June 26, 1914

Looks can be deceiving, but my first impression was that Adelard looked like a nice kid, confidant and relaxed in front of the camera, and perhaps a bit amused by Mr. Hine. I carried that impression further and imagined that he came from a loving family of recent French-Canadian immigrants, and though his days were often a struggle, he was relatively content with his life so far, and hopeful for the future.

He couldn’t have imagined the challenge his family would soon face. Less than three years after he posed in front of the Naumkeag Steam Cotton Company mills, a devastating fire wiped out much of Salem, including the apartment building at 43 Prince Street, where the Gagnons lived, and the mill where Adelard and many of his 12 siblings were working. The following newspaper articles detail a series of events from the day of the fire, until the mill was rebuilt and the company continued its record of sound business practices and, apparently, good labor relations.

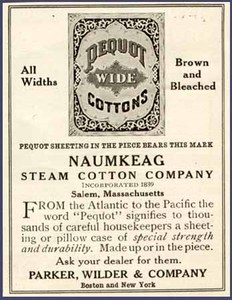

“Unique among the cotton manufacturing enterprises of New England, and also among all the mill companies of this section, the Naumkeag Steam Cotton Company of Salem is preparing to have its whole new plant, probably the most complete and up-to-date cotton mill in the country, in operation within a month.”

“In June 1914, the disastrous Salem fire wiped out all but one small storehouse of the corporation. Since that fire the company has rebuilt its plant, installed the latest machinery, paid dividends regularly at the annual rate of 10 percent, and still has the largest surplus in its history — more than $2,000,000.”

“This achievement was made possible by uncommon foresight on the part of the management in placing its insurance. At the time of the Salem fire the mills were insured to cover loss by fire on buildings, machinery and stock, but there was also ‘use and occupancy’ insurance to cover loss of production.”

“This use and occupancy insurance has taken care of the 10 percent annual dividend requirement. With the proceeds of the insurance on the plant and stock, the company has been able to rebuild in such a way as to make its present situation probably the most favorable in its history.” –Boston Daily Globe, January 6, 1916.

The following is from Life and Labor Bulletin, published in 1926, by the National Women’s Trade Union League.

One of the outstanding organizations of women workers within the labor movement can be found in the Naumkeag Steam Cotton Company of Salem, Massachusetts, where the United Textile Workers of America have a 100 per cent local union of over 2,000 members of whom more than 1,600 are women, all engaged in the manufacture of Pequot sheets and pillow cases.

This organization is a notable exception to the rule in the textile industry, and has created considerable comment for its progressiveness in union affairs. Since it was chartered in 1918, it has overcome the many obstacles presented to women’s organizations, and has achieved some notable success in trade union technique.

This organization has since its early struggles been functioning under a system of recognition of the union, collective bargaining in its fullest sense, seniority rule and a standard productive system as a requisite to perfection in quality.

Pequot sheets and pillow cases have been made since 1839, and the demand has been so great that this mill has had no unemployment or labor turnover problems. It has operated continuously since the conflagration at Salem in 1914, after which a new mill of the most modern and sanitary type was erected. This is believed to be the only mill in the textile industry to have not been affected in the recent periods of depression.

These workers on Pequot were the only workers who did not receive the general reduction of 10 per cent in 1925, in comparison to other sheeting and pillow case plants, their wages are in excess 20 per cent, their conditions of work unchanged, while other sheeting workers have been forced to adopt increase in machines with decreases in price rates.

They have been free from strike since 1919, and the union and management have both found in collective bargaining a solution of their industrial problems during this period.

Lewis Hine caption: The very smallest boy is Henry Fournier, 261 Jefferson Ave., Castle Hill, has worked 2 months in #2 Spinning Room. The next in size is Adelard Gagnon, 32 Perkins St., works in Spinning Room. Next in size (front row) is Adelard Dion, 1 Palmer St., works in #1 Spinning Room. Smallest in back row is Albert Valbert, 14 Park St. Location: Salem, Massachusetts, October 1911.

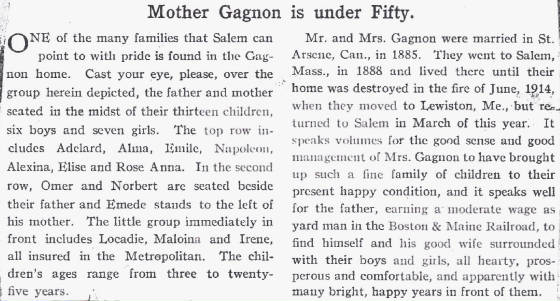

Top row (L-R): Adelard, Alma, Emile, Napoleon, Alexina, Elise, Rosanna.

Top row (L-R): Adelard, Alma, Emile, Napoleon, Alexina, Elise, Rosanna.

Second row (L-R): Omer, Norbert, Elie (father), Adele (mother), Amedee.

Bottom row (L-R): Leocadie, Malvina, Irene.

The photograph and article above were the work of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, apparently as a promotion for selling life insurance, by showing that the Gagnons, a locally well-respected family, had chosen to obtain life insurance while they were still relatively young. Because Mr. and Mrs. Gagnon were French-Canadian immigrants, a growing and highly represented demographic in the area, the company probably was attempting to appeal to that potential market. By agreeing to appear in the advertisement, the family may have received modest compensation, such as a discount on the insurance. The photograph would have been taken in 1916. According to the grandsons, the company misspelled several of the children’s names. They also stated incorrectly that Mr. and Mrs. Gagnon married in 1885. According to their Canadian marriage record, they married in 1886.

I had not seen the photos of Adelard Gagnon until I received an email from one of his grandsons, Ron Gagnon. In part, he wrote:

“A colleague pointed me to your website, particularly about your efforts to identify people in Lewis Hine photos. My grandfather, Adelard Gagnon, is in two of the Lewis Hine photos taken in Salem, Mass. He is identified, fortunately, and that’s how the colleague found them on the Library of Congress website. Neither my mother, nor my aunts and uncles, knew of the pictures, so they were a complete surprise to us all. If you need any other info, please let me know.”

I interviewed Ron, and another grandson, Ken Gagnon, Ron’s first cousin. Ron provided me some photos of Adelard, and several delightful and informative newspaper articles about Adelard and the history of the Gagnon family.

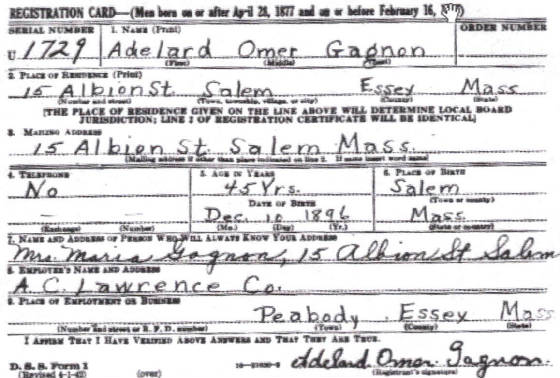

According to official Massachusetts birth records, Adelard was born Joseph Omer Adelard Gagnon, in Salem, on December 10, 1896. That means he was 14 years old when he was photographed, making him a “legal” worker, since the Massachusetts age limit for children in mills was 14 at that time. His parents were Elie Gagnon and Adele Berube, both Canadian born. They married in St. Arsene, Quebec, on May 4, 1886. Adelard was the seventh of 13 children. He quit school after finishing the seventh grade, and married Maria Bolduc in 1917. They had four children. He passed away in Danvers, Massachusetts, on January 19, 1979, at the age of 82. Maria died in 1990.

Excerpts from an email from Ron Gagnon, grandson of Adelard Gagnon, and son of Adelard’s son, also named Adelard. Also included are excerpts from a subsequent interview with him on January 15, 2013.

“The Naumkeag Steam Cotton Mill is the mill where my grandfather was photographed. It was known more popularly as the Pequot Mill, Pequot being a brand of sheets, etc. There was a great fire in Salem in 1914, which destroyed the mill as well as much of the city. Because of the fire, my grandfather and his family moved to Lewiston, Maine, where they lived with his uncle. They lived there a year until the mill was rebuilt and operating.”

“His parents came to Salem in 1888, from St. Arsene, Canada. He lived at 32 Palmer Street, until he got married to Maria Bolduc, in November 1917, so the 32 Perkins Street in the caption is incorrect. (According to the Salem directories, he lived at 43 Prince Street from 1913 to 1915, and at 57 Harbor Street from 1916 to 1917.)

After they got married, he and Marie moved to the second floor of his in-laws house at 17 Albion Street. Their first child, Edward, was born in December 1918. In January 1920, they had their only daughter, Malvina. Sometime in 1920, they moved to Dow Street, and then sometime in 1921, they moved to Harbor Street. Both of these locations are near the mill, in what was then the French section of Salem. In November 1922, they had another son, Adelard (my father). In 1926, they had their last child, George.”

“In 1935, he lost his job with the Naumkeag mill. They moved back to Albion Street, this time next door to the in-laws. At that time, my grandfather began working for A.C. Lawrence Leathers, a tannery in Peabody. He loaded skins in carts to transport between sections of the factory for the next process. My father also worked at A.C. Lawrence for most of his work life until it closed in the early 1970s.”

“In 1948, they moved to a house at 16 Appleton Street in Danvers. I was born in 1956, and lived in his house the first couple of years. He retired from A.C. Lawrence in 1961, and got a small pension. My grandmother had a debilitating stroke shortly after his retirement, so he became the house husband, taking care of her and the house. He enjoyed his garden, particularly growing tomatoes, which he shared with family and neighbors. He also had some fruit trees. I remember that he seemed happy in retirement, and happy to be at home.”

“The neighborhood kids all came to visit my grandfather, and he would give them lollipops. He never had a driver’s license, so my father did his grocery shopping for him, including looking for sales on lollipops, particularly the ones in long clear strips. And his neighbors would take him to Mass every week. They stayed there until about 1978, when it became too much for him to take care of my grandmother and the house, so both of them went into a Danvers nursing home. He passed away in January 1979.”

“They lived very frugally, even to the end, as is typical of the Depression-era folks. I think he was unemployed for quite a while in the thirties, or at least it made a big impression on the stories I’ve been told of my father’s childhood. My grandfather worked for the WPA, but I’m not aware of any particular project. They also had to scrounge for fuel for the stove (scrap wood, old barrels), and used cardboard to block the holes in their shoes.”

“He would have all the kids in the neighborhood bring him newspapers, and he’d give them all a lollipop. He would stack them in his garage, and then his next door neighbor would load them on his pickup truck and drive them to the recycling place, and he would get a little money for them. He was a bit of a collector. If you needed a piece of glass or something, he’d go down to his cellar and come up with it. Even though my grandfather was born in this country, he always spoke with a French Canadian accent. He had a great sense of humor. He was a nice guy, and he was very warm to me.”

Excerpts from my interview with Ken Gagnon, grandson of Adelard Gagnon, and son of Adelard’s oldest son, Edward. Interview conducted on February 5, 2013.

“I was born in 1957. I only lived one year in Massachusetts. That was when I was four years old. Other than that, the only time I spent with my grandfather was three weeks out of every year when we went to Massachusetts for vacation.”

“He smoked cigars and pipes. We used to bring him a box of cigars every year when we came up to visit. He would rather have a box of 100 of a cheap brand than 10 of a good brand because, as he said, he could smoke them 10 times longer. He would smoke them down to a nub, just about at the point where they would burn his lip.”

“When we moved my grandparents out of their house in Danvers, I helped clean out the basement. They had aluminum pie tins, empty medicine bottles, twine, and all kinds of stuff he thought would come in handy one day.”

“Every year for Easter, my parents would buy my grandfather 100 baby chicks, and he would raise them in his back yard, and then butcher them and sell them. He used to use an old chicken bone for the hasp on the gate to the yard, instead of a padlock. He sure had his way of doing things. I still have that bone in my keepsake box.”

“I remember Dad telling me a story that my grandfather used to collect newspapers from some of his neighbors. About every month or so, he would give a stack of them to a guy who sold fish out of his truck. The guy would use them to wrap the fish. In return, the guy would give him some fish, and my grandfather would share the fish with the neighbors that gave him the newspapers.”

Note: If the story about Adelard collecting newspapers sounds familiar, that’s because it’s a variation on Ron’s story about Adelard collecting newspapers to sell to a recycling center. I asked Ron which version was correct, and this was his answer.

“Ken’s story sounds right. I know my grandfather did have a regular visit from the fish guy. My grandfather gave us fish every so often. He definitely had enough newspapers to go around, so both stories are true.”

The following are excerpts from an article published in the Salem News in 1989. Quoted with permission.

“One hundred years ago, Elie and Adele Gagnon bundled blankets around their infant son, Napoleon, and left their home in St. Arsene, a community on the shores of the St. Lawrence River in Quebec, Canada. They journeyed to America.”

“The young family settled in Salem, in a neighborhood of tenement buildings known as the Point, following other French-Canadian families who had moved into the area over the past decade to build the Pequot Mills. The Gagnons soon became part of Salem’s growing French community. Families spoke French at home, children attended French-speaking Catholic schools. French-Canadian immigrants worked together at textile mills and bought groceries from French-speaking merchants.”

“‘We couldn’t play with other kids because we didn’t know English,’ said 87-year-old Malvina Gagnon Jalbert (Adelard’s sister), the only one of Elie and Adele’s 13 children still alive. That devoted French community remained strong enough through the 1950s, but as the great-grandchildren of Elie and Adele began to earn college degrees, the Point’s French community slowly shrank, then scattered across the country.”

“After they left Canada 100 years ago, Elie and Adele Gagnon moved to Perkins Street and raised a family of 13 children. Elie Gagnon worked as a track man for the Boston and Maine Railroad for 39 years and often brought home railroad ties, which were burned to heat the house.”

“Adele Gagnon not only cared for her children, but also cooked steak and potatoes each morning, worked at the mills, dashed home during breaks to feed her youngest daughter, baked 12 pies each Saturday and washed clothes on a scrub board until a wringer washing machine could be afforded.”

“She also made the family’s clothes, tearing apart old coats to sew new ones. ‘Once she took an old umbrella and made a dress for me,’ Malvina Jalbert said. ‘She also made me a sailor suit. I loved it. I looked so good in it.'”

In 1914, the Gagnons lost all their possessions in the great fire that devastated Salem. As the fire moved toward their house, Adele Gagnon sprayed holy water throughout the rooms as a form of blessing, but her prayers couldn’t stop the flames. Malvina, who was 11 years old, remembers a cousin banging on the door, demanding the family leave the house. The family lived in tents on Salem Common with other fire refugees, moved to Maine, then returned to Salem once the Pequot Mills were rebuilt.

Each of Elie and Adele’s 13 children worked at Pequot Mills, some as early as 14. Malvina was 16 years old when she began a spinning job in the textile mill.

The following are excerpts from an article published in the Danvers Herald, in 1977. Quoted with permission.

“Sixty years of marriage. After recently celebrating that monumental anniversary, Adelard and Maria Gagnon of 16 Appleton Street confided that they wouldn’t want to spend their lives any differently than the way they have. According to (Adelard) Gagnon, the origins of a successful marriage are to be found in a person’s childhood family life. It is there, he claims, that parental relationships are learned, that good family living is formed. He laments the dissolution of extended-family life, equating that decline with the increase of unstable marriages.”

“When I was a boy families were close. Do you know that on New Year’s, we all would (13 children) go before our father to receive his blessing? We would kneel down before him and he would put his hand on our head and say, ‘I wish you luck in the coming year,’ and then shake our hand. People would laugh at that now, but it made us feel happy and warm. Older people know what I am saying, younger people don’t.”

“Christmas was nice, too. We had a ritual where the oldest child would get the next oldest, and so on, until we were all gathered; we would then walk together to our parents’ room to shake their hands and wish them a Merry Christmas, and they, us. There were lots of nice things to eat that day. Our mother would have been cooking from three or four o’clock in the morning. The family mattered. She cared.”

“How, in 1916, did a young man from Harbor Street, Salem, meet a young lady from Fall River?”

“Maria’s family moved to Salem when she was 12. We met at a carnival. My cousin and I were wandering around talking about girls when I saw Maria. I began talking to her and then took her on a couple of rides on the merry-go-round. I took her home that day. In those days there was a time when you had to be home, so I told her we would meet again, and began visiting her. Of course back then, that meant sitting in the parlor with Maria and her mother. There was no kissing. You just talked and got to know each other. We were married a year and a half later, on November 18, 1917.”

“The Gagnon’s tales are as endlessly enjoyable as they are inexhaustible – as will attest three regular visitors. The three Danvers High School students began visiting the Gagnons ‘as a project for Mr. Farley’s class, Project Senior Citizen,’ but now visit the Gagnons for the pleasure of their company.

“His stories about the old days are great. He really cares about us. He’s always cautioning us to be careful. He’s so funny. We really love them.”

Adelard Gagnon: 1896 – 1979.

*Story published in 2013.