Chapter Five: Discovering Addie’s Adopted Family

The city of Cohoes (pronounced Ca-hose’) was once the home of Harmony Mills, one of the largest in the world. The yarn-producing factory along the Mohawk River was powered by Cohoes Falls, which was the subject of a famous painting created from a 17th-century sketch by, oddly enough, a man named Thomas Pownal. Most of the mill buildings still stand, housing some small industry and a large outlet store. Recently, a developer has received approval and partial government assistance for his plan to convert the buildings into apartments and retail shops.

Carole and I visited Cohoes a few years ago on a weekend trip through the Mohawk Valley. Its downtown was all but deserted, and a recently closed Woolworth’s seemed to symbolize the city’s hard times. We walked around, bought some sheets at the Harmony Mills outlet store, and headed to Troy.

As we would learn, Addie spent most of her last 50 years in Cohoes, where she struggled in various factory jobs, and lived in subsidized housing. It is also where she was given a second chance at motherhood, and wound up endearing herself to three generations of grandchildren.

On November 14, Carole and I made the two-hour drive to Cohoes, arriving at St. Agnes Cemetery by mid-morning. It took about two minutes to find Addie’s gravesite, and there was a surprise waiting for us. It was a flat gravestone, and on it, besides her name and years of birth and death, there was the following in quotation marks: “Gramma Pat.” Carole said, “Now we know that when she died, there must have been someone who loved her very much.” But why Pat?

I pulled out my cell phone and called Elizabeth. It had been exactly four weeks since my search had begun. She said, “You’ve gone from A to Z now.” But the journey was far from over.

I took some photos, and then we went to the funeral home that handled the arrangements. They found a newspaper obituary and ran off a copy for me. The obituary listed her daughter Ruth; a second daughter, deceased; three grandchildren; three great-grandchildren, and two great-great-grandchildren (all descended from her second daughter). This added a whole new list of contacts, with the prospect for photos and plenty of information about the last half of Addie’s life.

We went to the public library and looked through a large collection of city directories. We found that Addie and Ernest were living as a married couple in Cohoes as early as 1940. We also established that she lived in a public housing facility in Cohoes for most of her last 20 years. Armed with a good city map, we drove to all of her known past addresses and took photos of several houses, including the last one she lived in.

We also found Addie’s sister, Annie Leroy, in the directories and established that she lived with her husband in Cohoes from 1919, until her death in 1954. We found the house and photographed it. We also went to the cemetery in neighboring Waterford and found the location of Annie’s gravesite. Unfortunately, the family plot said only Leroy on the headstone.

Then we looked for a place for lunch. We wound up at the Golden Krust Bakery, a restaurant that, according to the menu, had been in business for more than 50 years under the ownership of several generations of one family, and specialized in Polish food. It was packed. We looked around and wondered if Addie had ever eaten there.

When we got home, I began the search for Addie’s second family. I tried the Internet white pages and came up empty. One of her great-granddaughters had an unusual name (Piperlea), so I thought it would be the easiest one to search on Google. Eureka! I came up with her picture and an article about her receiving an award from a local college. The award was presented by the registrar, whose email address I found on the college Web site. I wrote a letter to Piperlea and emailed it to the registrar, asking her to forward it, hoping she would have her contact information.

While doing some research on Ernest LaVigne, I found his WWI draft registration record from 1918, and he listed North Adams as his address, and his father, at the same address, as his nearest relative. Ernest was working at the Beaver Mill, one of the oldest textile mills in the city. It occurred to me that Addie might have met Ernest in North Adams, since at that time, it was just a short trolley ride from Pownal. I searched the directories for Addie Hatch and found her living by herself in the city in 1921.

A few days later, I was back in Hoosick Falls and Bennington. When I found no record of Edward Hatch’s marriage to Elvina in Bennington, I had a hunch that they might have gone across the border to Hoosick Falls. So I checked at the Hoosick Town Hall and found their marriage certificate. They had been married just six weeks after Edward divorced Addie.

Back home again, I continued to search the Internet for the surviving members of Addie’s second family. A week went by, and there was no reply to my email to Piperlea, the great-granddaughter. I was getting discouraged. One evening, the phone rang. It was Piperlea.

She was very excited and wanted to tell me all about Addie, whom she called “Gramma Pat.” She had never seen Addie’s famous photograph, and apparently Addie hadn’t either. She told me that Addie and Ernest adopted a baby daughter soon after getting married, and lived for a while in New Jersey and New York City. That adopted daughter died a few years ago in Cohoes. The young woman I was talking to was the granddaughter of Addie’s adopted daughter.

After notifying Elizabeth, we made arrangements to interview members of Addie’s adopted family. Waiting for us would be photos of Addie, including one of her in New York City on VE Day, and one when she was 90.

Shortly after the New Year, Elizabeth, Carole and I traveled to Troy, New York, to interview Piperlea and her mother, Cathleen. They provided many photos of Addie and her family. It was an illuminating and emotional three-hour visit, both for us and for them. We learned so much about Gramma Pat (she changed her name to Pat because she didn’t like Adeline). As an added bonus, the research Elizabeth and I had done provided a lot of new information about Addie that the family didn’t know. (See the full interview and more photos on the following pages.)

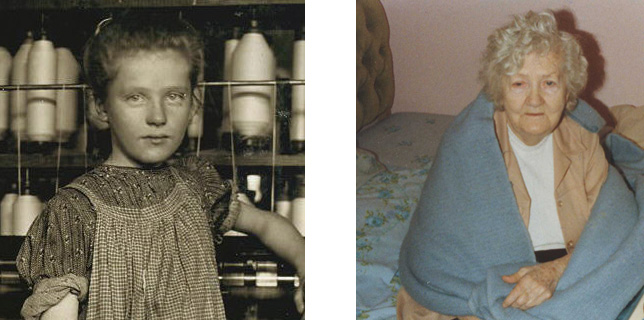

It had been a whirlwind three months since my dinner with Elizabeth in Williamstown. In that short time, it felt like Addie had become a member of my family. As we said our goodbyes to Addie’s family, I noticed two framed photos side by side on a nearby shelf: Lewis Hine’s photo of Addie when she was 12 years old, and Addie when she was 90 years old. If only Hine could have been there with us.