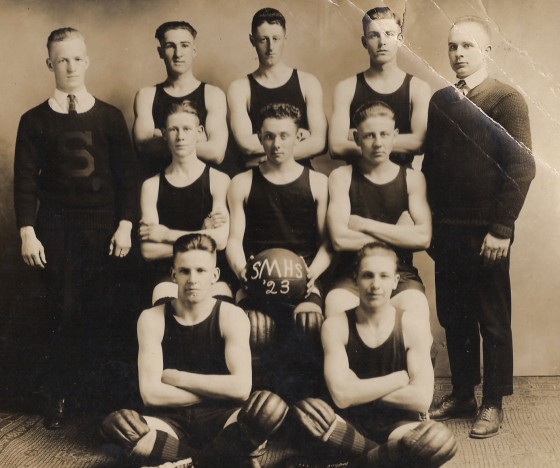

Lewis Hine caption: Three cutters in Factory #7, Seacoast Canning Co., Eastport, Me. They work regularly whenever there are fish. (Note the knives they use.) Back of them and under foot is refuse. On the right hand is Grayson Forsythe, 7 years old. Middle is George Goodell, 9 years old, finger badly cut and wrapped up. Said, “the salt gets unto the cut.” Said he makes $1.50 some days. Left end, Clarence Goodell, 6 years, helps brother. Location: Eastport, Maine, August 1911.

“That’s what everybody was doing in those days. If you lived on a farm, you had to do chores all the time. If you lived in a fishing village, you had to work in the fishing industry.” -Grayson Forsyth, grandson of Grayson Forsyth

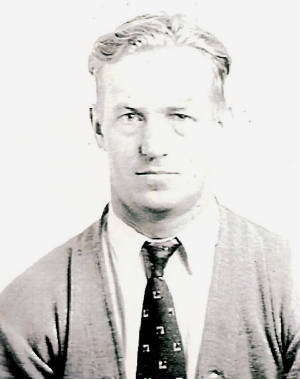

“My father was as strong as an ox. He was only about 5′ 6″. But you have to understand that these guys grew up tossing 400-pound barrels. He was all muscle.” -Richard Forsyth, son of Grayson Forsyth

The following is the testimony of Everett W. Lord, at the Sixth Annual Conference of the National Child Labor Committee, held in Boston in January of 1910, 19 months before Grayson was photographed. Mr. Lord was the Secretary for the New England branch of the National Child Labor Committee.

”I want to say a word about the canning situation in Maine. It is a report of progress, a progress of science, not of legislation, because the canners of Maine have succeeded in defeating every attempt to restrict labor in any way in the sardine canneries, child labor, the hours of labor for adults and everything else. They have no restriction whatever. The law is entirely open for the sardine canners.”

“At the last legislature the men who make cans came up and asked to have the same exemption extended to them. The canners had the exemption on the ground that the fish were perishable. Now, the canmakers came up and said the cans are also perishable, they rust very quickly and must be made up in great numbers when they are needed right away. We found that the people who were making the boxes in which the cans were placed wanted a similar exemption because the cans had to be boxed so quickly, and many others were following on that trail to get exemptions. I am glad to say that while we were unable to make any progress, we were able to stop that. No further exemptions were made. Now, however, in some of the largest canneries on the coast of Maine they are putting in machines which will do practically all the work now being done by children. As soon as those are in operation the large canners will be very glad to have a law passed prohibiting employment of children, and I hope we may get a law which will remove that exemption. Our prospects are pretty good. The sardine industry is the only important one which now employs great numbers of children.”

**************************

Grayson Forsyth was only six years old in this photograph. He would turn seven in two months. Lewis Hine found many very young boys and girls who were fish cutters. His companions, George and Clarence Goodeill, are the subject of another story on this site. It didn’t take me long to find Grayson’s descendants, since one of his grandsons has the same name. The family already knew about the photograph.

On this summer day in Eastport, Grayson would have walked to work from his house at 11 Hawkes Avenue, probably heading east, turning right on High Street, and left on Pleasant Street. It would have taken him less than 10 minutes. Seacoast Cannery Factory #7 was on the southern end of the city, where Pleasant Street and Dawson Street meet on the edge of Passamaquoddy Bay.

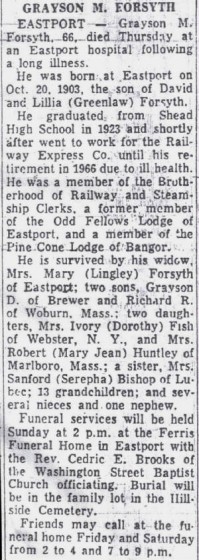

Grayson Mitchell Forsyth was born in Eastport on October 20, 1903. His father was David Forsyth, who was born in Nova Scotia. His mother was Lillia Jane Greenlaw, who was born in Eastport. They married about 1892. David was a hardware salesman, and later a bookkeeper for a grocery store. He died in 1936. Lillia died in 1943. They had six children, but one of their daughters, Helen, died very young.

Grayson married Mary Lingley in Eastport, on April 9, 1929. They had two sons and two daughters. Grayson worked most of his adult life for Railway Express, a delivery company. He died in Eastport on December 11, 1969, at the age of 66. His wife Mary died in 1991, at the age of 80. I interviewed their son, Richard, and Richard’s son, also Grayson, at their home in the Boston area.

Edited interview with Richard Forsyth and his son Grayson, son and grandson of Grayson Forsyth. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on June 28, 2011.

JM: How did you already know about this photograph?

Richard: A friend of mine in Eastport saw it and sent me a copy.

JM: Did you know that your father worked at the cannery at a young age?

Richard: Oh, sure. Thirty years later, I was cutting fish at the grand old age of 10. That was about 1944. I cut alewives at a cannery that did pickled alewives. I had to cut off the head and scrape the backbones at the same time. Everybody was working in those days. I don’t think it ever hurt me. I think it made me a better person. It was sort of like working in the family business.

JM: Was that just in the summer that you worked at the cannery?

Richard: The alewife season is in the spring. I used to come home from school, put my gear on, and go down and cut the rest of the afternoon.

JM: Who were you working for?

Richard: Burpee Wilson. He also had a paint factory, which was right next to the pickled fish factory, and he also packed sardines on a limited basis.

JM: In the summer, when you were not going to school, did you work there all day?

Richard: No. I had a newspaper route most of the time. I started delivering newspapers when I was seven years old.

JM: How could you have worked at the age of 10? That was illegal then.

Richard: It came down to the fact that somebody had to cut the fish. My older brother and sister did it, too. I was able to get away with it. I always had fishing line in my pocket when I worked there. That was very, very important. If the inspectors came around, I suddenly had to get away from the table where I was cutting the fish. So I would go out and pretend I was fishing.

Most people don’t understand Eastport. When I was growing up, I thought the sardine business was just a dirty business. As I matured, I realized that the lifeline of Eastport was in that business. The train was in Eastport for a reason, to ship the products from both Eastport and Lubec. People don’t realize that those towns couldn’t survive without those factories. But they went bankrupt in the thirties. The Depression killed them. My father always said that the worst thing that ever happened to Eastport was the Depression. People lost their pride, and some of them never gained it back.

My father worked for Railway Express Company. He was delivering for them. He drove a truck, but sometimes, he had to go on the train. He worked on a commission. It was hard. Sometimes he only worked 12 hours a week. Consequently, he had to pick up other jobs. He fixed coal furnaces.

In 1948, my father had an angina attack. I was a freshman in high school then. His whole family had heart problems. He had that problem until he died. The only medicine they had was nitro. I worked with him at the Railway Express office off and on until I went to college. In my junior year, my father was having a lot of problems, so I helped him run the office the whole summer.

I didn’t know what he went through in the Depression, because I was too young. But what I do remember about that period was that when something came for you by freight, you had to go down to the station and get it home no matter how much it weighed. When my father didn’t get any work from the company, he would rent the express truck and deliver freight by himself. He was paid by the people he delivered the stuff to. I can remember going with him.

He never had a holiday off. He felt a strong obligation to make sure his customers received things on time. I remember on Christmas Eve, we would all sit around together and exchange gifts, and then he would put on his coat and get in the truck and be gone until late at night. That was the way he was.

JM: How did he load the heavy stuff into the truck?

Richard: My father was as strong as an ox. He was only about 5′ 6″. But you have to understand that these guys grew up tossing 400-pound barrels. He was all muscle. When my parents got married, they moved to Portland (Maine). My mother was thrilled to get out of Eastport. But then my father’s father got injured on the job and couldn’t work, so they had to go back and help out. Then the Depression came.

When I was very young, he bought a house nearby on the same street. The house was in terrible shape. He spent many years putting it back together again. He never really got to enjoy it. When you live by the ocean, the paint on your house never stops peeling, and you never stop painting. The house was decorated with more than a thousand little pieces of raised wood along the roof and all along the side. He painted each one of them individually. I said to him one day, ‘Why are you doing that?’ He said to me, ‘If I don’t do it, I’ll know that it is not the way it should be.’ I don’t know how he had the patience to do that. He lived in that house until he died, on December 11, 1969. He was 66 years old.

JM: Did your mother work when you were growing up?

Richard: In about 1940, she worked at the Holmes Cannery. When the woolen mill came in, she started working there, and she stayed there until she retired. She was still working when my father died. She died at the age of 80.

JM: Did you graduate from high school?

Richard: I graduated in 1952, and then I went to the University of Maine. I studied mechanical engineering.

JM: How did you pay for it?

Richard: I always worked in the summer. I paid the bill for the fall semester, and my father paid for the second semester. I said to my father one day, ‘I’m going to have to pay you back a lot of money.’ He said, ‘You don’t owe me anything. But when it comes your turn to do this for your kids, make sure you do it.’ My younger sister also went to college.

JM: What did you do after you graduated from college?

Richard: I went to work for Texaco, in Fishkill, New York. Then I had to go into the service. When I got out, I went to work at Raytheon, in Waltham (Massachusetts). I worked for them from 1958 to 1963. After several other jobs, I returned to Raytheon, this time in Wayland, and later in Bedford (both in Mass.) I eventually got laid off, and then I worked for a small company in Hudson (Mass.). I ended up back at Raytheon, and retired from there.

JM: How often do you get back to Eastport?

Richard: At least once a year for about a week.

JM: Grayson, what do you think of the photo of your grandfather?

Grayson: He looked exactly like I did when I was eight years old. I was born in 1967, so he died when I was two years old.

JM: What do you think about the fact that he was working at such a young age?

Grayson: I don’t have any problem with it, because I started my own paper route when I was 10.

JM: But isn’t that a lot different than using a big knife to cut fish at a cannery? And he would have worked a lot more hours.

Grayson: Yes, you’re right, but I don’t think there was anything wrong with it. That’s what everybody was doing in those days. If you lived on a farm, you had to do chores all the time. If you lived in a fishing village, you had to work in the fishing industry. His parents were professional people. His mother was a teacher, and later on a nurse. His father was an accountant. Children are a reflection of their parents. My grandfather graduated from high school and got a football scholarship to Springfield College (Mass.), although he decided not to go. He owned his house and paid it off as soon as he could. And that was the 1930s, during the Depression. He accomplished a lot.

Photos and images provided by Forsyth family, unless otherwise noted.

*Story published in 2013.