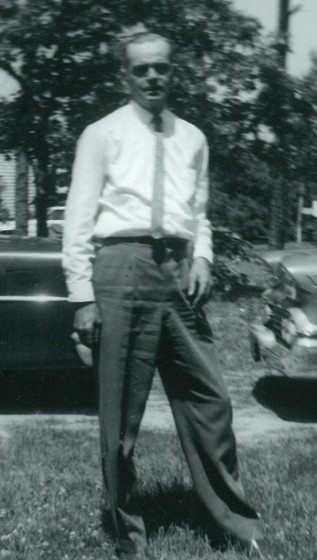

Lewis Hine caption: Jose de Sousa Magano, 35 Aetna St., Fall River, Mass. Born in Fall River, June 2, 1901. Left for the Azores at 8 years of age because family moved back. Cannot read or write in his own language or in English. Never been to school. Returned to Fall River in May 1916. Applied for employment certificate June 17, 1916. Refused on account of not being able to read or write. Will have to attend school until he is 16 years of age. Presented baptism certificate from Santo Christo Church, Fall River, as evidence of his age. Sister had to talk for him. Could not understand or speak English. See 4192. Location: Fall River, Massachusetts.

“He loved to read. He loved newspapers. He loved to discuss current events. He had an opinion about everything, and he was always eager to share it.” -Maureen Conboy, granddaughter of Joseph Magano

**************************

The following are excerpts from the Massachusetts child labor law that was in force in 1916.

“No child between fourteen and sixteen years of age shall be employed or be permitted to work in, about or in connection with any factory, workshop, manufacturing, mechanical or mercantile establishment unless the person, firm or corporation employing such child procures and keeps on file accessible to the attendance officers of the city or town, to agents of the board of education, and to the state board of labor and industries or its authorized agents or inspectors, the employment certificate as…issued to such child.”

“The school record required shall be filled out and signed by the principal or teacher in charge of the school which the child last attended and shall be furnished only to a child who, after due examination and investigation, is found to be entitled thereto. Said school record shall state the grade last completed by such child and the studies pursued in completion thereof. It shall state the number of weeks during which such child has attended school during the twelve months next preceding the time of application for said school record…no employment certificate shall be granted unless the child possesses the educational qualifications…ability to read, write and spell in the English language as is required for the completion of the fourth grade of the public schools of the city or town in which they reside.”

**************************

Lewis Hine was an employee of the National Child Labor Committee, a private organization whose main objective was to investigate and publicize the practice of child labor in the United States, and to persuade politicians and the general public to support laws to abolish it. Hine was assigned to take pictures in various locations, often in states where proposed child labor laws were being hotly debated, or in states where child labor laws had been recently passed.

In June of 1916, Hine was sent to Fall River to document, among other things, if the Massachusetts law described above was being enforced. At that time, the US Congress was debating the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act, which would prohibit the sale in interstate commerce of goods produced by factories that employed children under 14, mines that employed children younger than 16, and any facility where children under 16 worked at night or more than eight hours daily. The bill had already passed the House of Representatives.

In one of his most impressive projects, Hine took almost 200 pictures of children in Fall River in a variety of settings and activities. He showed students participating in vocational school classes and arts events; kids hanging out at Sandy Beach, a park with a dance hall and carnival rides; boys playing crap games in the street; and even poor children scavenging at the dump.

But most of the pictures portrayed children working in textile mills or applying for work certificates, such as a handsome, well-dressed boy named Jose de Sousa Magano, who had turned 15 years old only two weeks earlier. Hine saw his baptismal certificate, so he was able to verify his full name and date of birth, and he learned other details from an older sister, who was in attendance. In this case, the child labor law was being enforced. Jose was not issued a certificate because he could not read and write in English.

Within minutes after I began my research, I found a Joseph S. Magano in the 1940 census. He was living in Fall River with his wife Lucy, and three daughters: Elsie, Hilda and Alice. He was working in road construction, and he had only a fifth-grade education. But was this the Joseph Magano who was in the photograph? It didn’t take long to find out. First, I found Joseph’s death record, and then obtained his obituary. One of his survivors was daughter Hilda (then Pavao). I found her obituary online, and that led me to her daughter, Maureen Conboy. I called her, emailed her the photo, and she recognized the boy as her grandfather right away.

Jose (Joseph) de Sousa Magano was born in Fall River, but his parents, Joseph and Marie Magano, were immigrants from the Portuguese Azores, nine small islands about 175 miles east of Portugal. Azoreans began coming to Fall River and other southeastern Massachusetts cities in the late 1700s. Most of the men worked on whaling ships. By the 1880s, they were also working in the mills, because whale oil was becoming obsolete due to the discovery of crude oil in Pennsylvania. At the same time, the Azores had become overpopulated and economically depressed, making the opportunities in the United States even more attractive. More than 100 years later, the Portuguese community continues to be a vital part of life in Fall River.

Joseph and Marie Magano, called Sousa in the 1900 census, were married in 1893, the same year they immigrated to Fall River. They already had three children by 1900. Mr. Magano was working as a fireman at one of the textile mills. For reasons undetermined, they returned to their homeland about 1907, with their children, including son Joseph. On May 31, 1916, they landed in Boston on a ship called the Cretic, and resettled in Fall River. Seventeen days later, young Joseph applied for a work certificate. When he was denied, he attended school and learned to read and write English. By 1920, he was a doffer at the King Philip Mills, where his parents and most of his siblings worked. King Philip was purchased by Berkshire Hathaway in 1930, and Joseph worked there most of his life.

Joseph (still called Sousa) married Lucy Pacheco about 1922, and they had all three of their children by 1930. In the late 1930s, he worked on road construction projects for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), most likely because the Depression had caused serious layoffs at the mills. At that time, it was discovered that his legal name was Magano, so he and his wife had to change their last names, although the children were allowed to retain Sousa.

Joseph passed away in Fall River on July 27, 1977, at the age of 76. His wife Lucy died on December 16, 1992, at the age of 90.

Edited interview with Maureen Conboy (MC), granddaughter of Joseph Magano. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on March 21, 2013.

JM: What was your reaction to the photograph?

MC: I had never seen my grandfather that young. I have a picture of him when he was in his twenties. I compared them. I looked at the mouth and the ears, and I knew it was him.

JM: When were you born?

MC: 1946. My mom was Hilda, one of my grandfather’s daughters. He and my grandmother had three children, all daughters. When I knew my grandfather, he was always working in the Berkshire Hathaway mill on Kilburn Street, the same mill my grandmother worked in.

When I was in third grade, my parents moved to Springfield (Mass.), where my father got a job. We were there for six years. But every year, I spent most of my summer vacation in Fall River with my grandparents. My little brother did not go with me. My grandparents lived at 530 East Main Street, at the corner of Dwelly Street and East Main. They rented it. It was a six-tenement house. They lived on the third floor, and my grandmother’s sister lived on the second floor. They had moved to that house after living at 35 Aetna Street, a few houses down from my grandfather’s parent’s house. That’s where they had all three of their children.

JM: What was it like living with your grandparents in the summer?

MC: My grandfather worked the first shift at Berkshire Hathaway. He worked in the carding room. He used to get up about three or four in the morning, and he was always home by lunchtime. My grandmother would have his lunch ready, and then she went to work on the second shift. She was a spinner on the looms. When she got out at ten-thirty, we had to go pick her up. It was just a short distance, but my grandfather didn’t want her to walk home in the dark. He would get there real early so he could always get the same parking space, and then we would have to wait for her. I remember being tired sometimes and lying down on the back seat.

In the morning when my grandfather worked, I’d be home with my grandmother. She taught me how to knit and crochet and sew. We would do a lot of sewing. Then my grandfather would come home at lunchtime. He was a meticulous man. He would wash up and change his clothes. He would wear a white shirt and a tie, and if he went out, he wore a suit and a hat. He did that every day. He had a beautifully trimmed mustache. I can still picture the mustache scissors hanging on a nail in the bathroom. I found a picture of him when he was sick and in his last years, and he had a turtle neck sweater on, and that was the only time I ever saw him dressed differently.

In the afternoon, I would go places with him, like the market and the park. He used to hang around a neighborhood park. It was called Father Kelly Park. All the old guys would sit on the benches. He had this old black Chevy that he loved. He would shine it, dust the inside and wash the windows, and I would play. Sometimes I would sit on the benches with the old men.

JM: Did he like to show you off to the guys at the park?

MC: I don’t know if it was me or the car he was showing off.

JM: Did your grandfather ever work anywhere else besides Berkshire Hathaway?

MC: During the Depression, before I was born, he worked for the WPA.

JM: In the 1940 census, he was listed as working on a road construction project. That must have been the WPA job.

MC: When he registered for the WPA, they found out that even though he was called Joseph Sousa and his wife and children were named Sousa, he actually was born Joseph Magano. They made him change his name and my grandmother’s name, but the kids were already in school, so they were allowed to keep the name Sousa. So my mother grew up as Hilda Sousa, but her parents were Maganos. It was very confusing.

The story in the family is that my grandfather was born in Fall River, but at some point, he went to back to Portugal. When it was time to bring all the kids here, they didn’t all come back at one time. One of the boys was supposed to come over, but he got sick, and they sent my grandfather instead.

JM: What kinds of things did your grandfather like to do?

MC: He loved to read. He loved newspapers. We would go to the Fall River Public Library. I would go into the children’s section while he would read the newspapers. He loved anything that was about current events, or politics, or geography. He loved to discuss current events. He had an opinion about everything, and he was always eager to share it.

My grandmother was a wonderful woman. She was the typical little Portuguese lady who loved to clean and cook. She was a wonderful cook. My grandfather loved fish, and she would cook him the whole fish, the head and all. I was grossed out by it. She didn’t like to go out much, but my grandfather loved to travel. He would read about places, and then he would go visit them. He traveled all over New England by himself, because my grandmother didn’t want to go. That’s what he would do on his vacation. He once went to California. He drove there by himself.

JM: Did your grandparents speak Portuguese?

MC: Yes, but they usually spoke English in the house, except when there was something they didn’t want us to hear. We always went to the Portuguese feasts in the neighborhood. He belonged to Our Lady of Angels, the Portuguese church. I called my grandfather Vavo, which means grandfather in Portuguese.

We moved back to Fall River when I was in the ninth grade. My parents separated, and my grandparents came to Springfield and helped us move. We moved into an apartment about three houses away from them. My mother had been working in Springfield, but she went back to her original job in Fall River, which was at the Little Dorothy Dress Shop. My father and mother eventually reunited.

After I graduated from high school, I worked a year in a factory, where I packed curtains. I managed to save enough to pay my way through nursing school. Back then, it was only $767 for three years, with room and board included. I worked as a nurse for quite a few years, and then I stopped working when my husband and I adopted a daughter. When she started kindergarten, I got a job as a school nurse, and I have been doing that ever since.

When we got married, we bought a house in Westport, just one town over from Fall River, about 15 minutes away. My mother thought I was going out to the boondocks. When my grandparents got older, they moved to Maple Gardens, which was partly an elderly housing project. My grandmother’s sister also moved there, and later, my mother lived there.

My grandfather had a wonderful sense of humor. When I was little, he took me to Plymouth Rock quite a few times. It was this big rock in Fall River that was up on a pedestal. I had learned about Plymouth Rock in school, and I thought that’s what I was seeing. I was always telling people at school about it. I told the teacher once that I touched it, and she told me that wasn’t possible. That’s when I started to wonder about it. And then I found out that my grandfather was joking, and it was actually called Rolling Rock.

Joseph Magano: 1901 – 1977.

The Keating-Owen Child Labor Act was passed by the US Senate and signed by President Woodrow Wilson in 1916, effectively outlawing most forms of child labor. However, the law was overturned by the US Supreme Court in 1918, the majority opinion stating that the law gave Congress too much power to regulate interstate commerce. Similar federal laws passed in the 1920s, but were also ruled unconstitutional. Nevertheless, child labor in the US declined substantially after World War I, thanks to a number of factors, including the progressive laws enacted by states such as Massachusetts. In 1938, most forms of child labor were outlawed by the federal government under provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act.

*Story published in 2013.