Lewis Hine caption: Minnie Thomas, 9 years old, showing average size of sardine knife used in cutting. Some of the children used a knife as large as this. Minnie works regularly in Seacoast Canning Co., Factory #7, mostly in the packing room, and when very busy works nights. Cuts some, also cartons. She says she earns $2.00 some days, packing. Location: Eastport, Maine, August 1911.

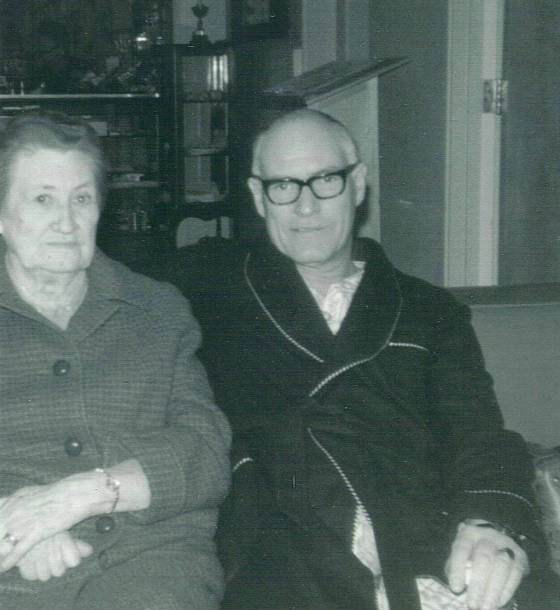

“When I saw the size of my grandmother and the size of the knife, I was amazed. I remember her telling me about working at a cannery when she was a girl. She said that when the inspectors came, the company would gather all the children and hide them in a room until the inspectors left.” -Lynne Hatt, granddaughter of Minnie Thomas

“I had heard some stories from my father about how hard it was back then, and how hard everybody had to work to make ends meet. I knew that children back then had to do lots of chores for the family, but to also be working in a factory; I never imagined that.” -Raymond Tucker, nephew of Minnie Thomas

This photo is a keeper. Sure, it’s carefully posed, but the point is well made and convincing. It begs the question: “Why is this nine year old girl allowed to use that huge knife?” And more broadly: “Why is she required to cut and pack fish all day and sometimes at night?” The power of this picture lies in Hine’s grasp of the little details. The knife is in the foreground, and because it’s stuck in the fence, right in front of Minnie, it looks even bigger than it is. Minnie is thin, and appears to be tall, especially since her arms are extended out toward the camera. So Hine takes advantage of the verticality of the scene. Notice the two posts at the far left, which match the position of the knife. Having her hold the fish in her hands seems contrived (what was she doing with them out there?), but they grab your attention and remind you what the knife is for.

In his earliest days as a photographer, Lewis Hine had an artist’s sensibilities. They are evident in his pictures of Ellis Island immigrants in 1905. Somehow, he knew how to compose them in such a way as to show the humanity of these weary but hopeful people entering a new world. By the time he began his 10-year journey for the National Child Labor Committee in 1908, he was both an artist and a skilled craftsman. But child laborers were a whole new subject for him, and they presented a daunting task.

Hine’s investigative role made him an unwelcome guest. Some of the children would have regarded him as a suspicious stranger, and his unfamiliar large camera as threatening. He had a limited amount of time to set up his heavy and cumbersome equipment. In those cases where he photographed inside a mill or other workplace, he had very little natural light. Given the nature of his mission, to induce a sympathetic and emotional reaction from viewers, and subsequent support for child labor laws, he had to compose his pictures carefully and purposefully. By 1911, when he photographed Minnie, he had become a consummate artist and a groundbreaking photojournalist.

Given the paternalism that was pervasive in factory towns at the time, and the strict disciplinarian attitudes toward children then, it is not surprising that Minnie would have patiently complied with Hine’s request to stand there while he went about setting up his shot. She would have learned to “do as you’re told.” It’s also possible that Hine believed that the location presented a good opportunity, and he had already set up his equipment and was waiting for a child to come along. Whatever the case, he created a magnificent picture.

I first saw the photograph in 2006, but I could not find a single record of the girl. So I reluctantly gave up. In the spring of 2010, having succeeded with more than a dozen children in Eastport, and having acquired some good sources of information in the city, I decided to give Minnie another try. I contacted the city clerk, who has been a great resource, but she could also find nothing on Minnie – no birth record, no marriage record, no death record.

Lewis Hine caption: Minnie Thomas, a 9 year old girl, works regularly in Seacoast Canning Co., Factory #7, Eastport, Me., mostly in the packing room, and when very busy works nights. Cuts some, and also cartons. Her mother said, “Some of the children cut their fingers half off.” Her father and grandfather are in the factory. She lives in Grand Manan in the winter with her aunt, father and mother live here. She says she earns $2.00 some days packing, not so much when she cartons. “Only made $1.70 all last week.” Location: Eastport, Maine, August 1911.

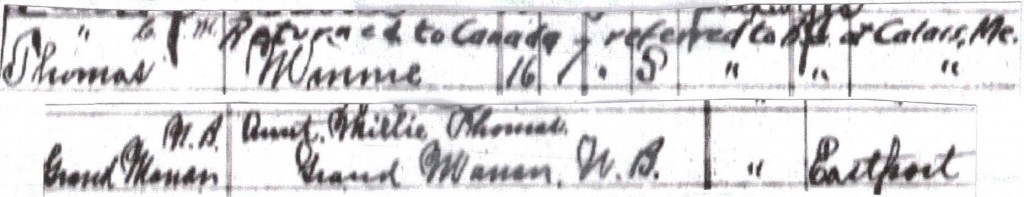

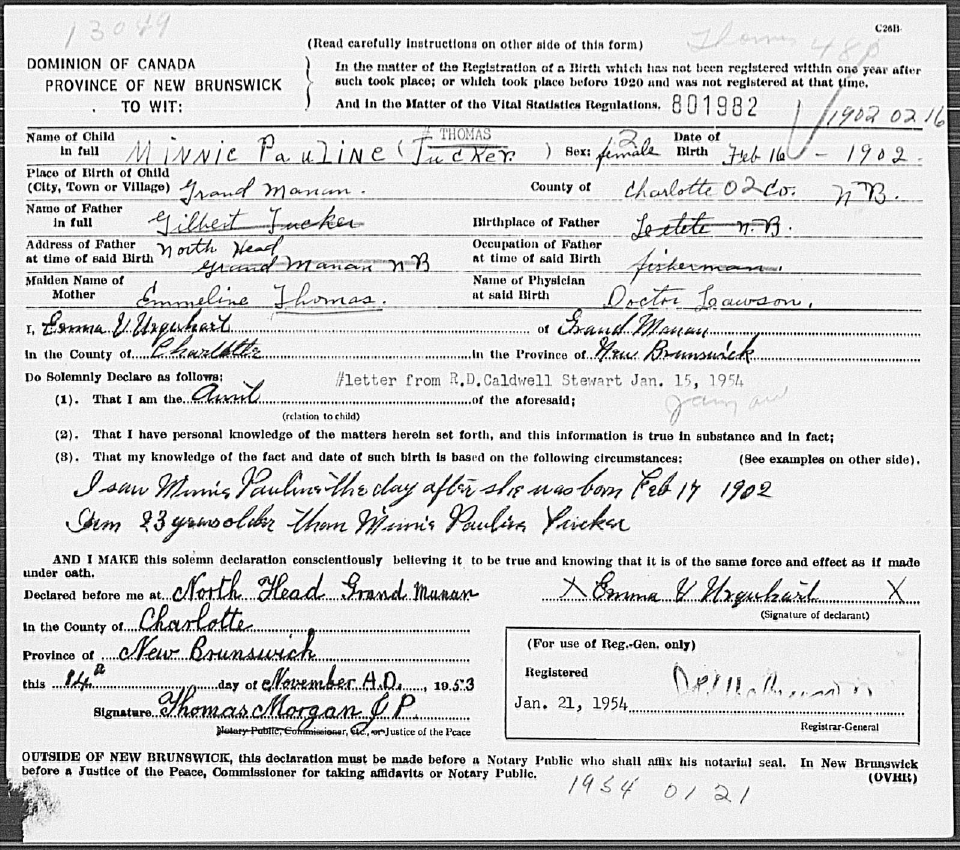

I took note that Hine mentioned in his caption of this photo of Minnie, “She lives in Grand Manan in the winter with her aunt, father and mother live here.” Just before I shut off the computer for the night, I took a quick look to see if there were any online records for Grand Manan, a small island community that is part of New Brunswick, and is just a short boat ride from Eastport. The first thing I came up with was a site called Provincial Archives of New Brunswick. It was name searchable, so I entered “Minnie Thomas” in the search engine. Her birth record popped up…just like that!

It said that Minnie Pauline Thomas was born on February 16, 1902, the daughter of Gilbert Tucker and Emeline Thomas (other records found later would say Emmeline or Nettie Emeline). There was another record of the birth, which was identical, except that Minnie’s last name was given as Tucker, which seemed more likely. After all, that was her father’s name. I went to bed, wondering what the morning would bring when I turned on the computer and followed up. It turned out that the discovery opened up the floodgates, leading me on a frenzied marathon search that revealed one intriguing (and confusing) nugget of information after another. In the space of about four hours, this is what I found, all based mostly on the Provincial Archives, the US and Canada censuses, and records of border crossings between Canada and the US.

Lewis Hine caption: Interior of a cutting shed in Maine. Young cutters at work, Clarence, 8 years, and Minnie, 9 years. Photo does not show the salt water in which they often stand, nor the refuse they handle. On the low shelf are two of the “boxes” used as measures, and for which they get 5 cents a box. Location: Eastport, Maine, August 1911.

It all started with Minnie’s parents. Gilbert Fenton Tucker was born in Grand Manan on September 18, 1875, the son of Angus Tucker and Teresa Holmes Tucker. Emeline Thomas was born in Grand Manan on October 20, 1876, the daughter of John Thomas and Harriet Guthrie (or Gutherie). Gilbert and Emeline married in Grand Manan on September 29, 1894.

They had at least four children, all born in Grand Manan: Cecil Fenton Tucker, born January 19, 1895; Evaline (Evelyn?) Tucker, born March 20, 1896 (per 1901 Canada Census, which also lists Gilbert’s occupation as a fisherman); Minnie Pauline Tucker (or Thomas), born on February 16, 1902; and Burton Albert Tucker, born July 12, 1905.

On March 26, 1910, Gilbert Tucker went to Eastport, leaving his family in Grand Manan, possibly to work in the canneries, since spring usually signaled the beginning of the canning season. He crossed again from Grand Manan to Eastport a month later, still without his family. Perhaps he didn’t find any work on the first trip.

In the 1911 Canada census, Gilbert, Emeline and son Cecil were living in Grand Manan with Emeline’s father, John Thomas. Minnie was not listed in the home (she might have been living with her aunt). In November 1916, Gilbert Tucker crossed again into Eastport, apparently without his family. In August 1917, Emeline, Minnie and son Burton came over, presumably to join Gilbert. Three months later, Cecil came over with his wife, Harriet. Interestingly, he listed his contact person in Grand Manan as his Aunt Millie Thomas. So I presumed that she was the aunt that Minnie was living with in the winter, as Hine’s caption noted.

In June 1918, something very interesting happened. Minnie (surname given was Thomas, not Tucker) crossed into Eastport, but was referred to authorities in the nearby town of Calais, and she was sent back to Grand Manan. No reason was given. Perhaps her parents couldn’t accommodate her. Perhaps there was no work available. Perhaps we will never know the reason. Anyhow, she also listed her contact person as Aunt Millie Thomas.

On April 30, 1921, Millie Thomas died in Grand Manan, at the age of 31. Her parents were John and Harriet Thomas, who were also the parents of Minnie’s mother, Emeline. So Millie was indeed Minnie’s aunt. She was listed as single.

According to the Maine State Archives, Minnie Tucker (Thomas?) married Vaughn H. French in Eastport, on September 27, 1936. He was born in Grand Manan on May 14, 1905, to Clinton and Hannah Cook French. He appears in the 1930 census, in Needham, Massachusetts, where he was a lodger and worked in a cotton mill.

Minnie’s father, Gilbert Tucker, died in Grand Manan on February 25, 1948, at the age of 72. Her mother, Emeline, died on June 2, 1953, at the age of 76. I thought I had reached a dead end at that point. I could find no further records for Minnie (now French), or Vaughn French. So I tried searching Minnie’s siblings.

Only Burton Tucker showed up in later records. He died in New Durham, New Hampshire, in January 1986 (exact date not given), according to the Social Security Death Index. I knew it was the correct Burton Tucker, because his given date of birth was the same as the one for Burton in the Provincial Records. But because I did not have the actual date of death, it was not likely that I could obtain his obituary from the local library in New Hampshire. So I put that aside and tried something else, which was a long shot.

I searched the Social Security Death Index for all persons named Minnie, with an approximate year of birth of 1902, and the place of death as Maine. I guessed that she might have died with another last name (not French), so that’s why I did not enter a last name in the search box. Surprisingly, there were 85 listings that fit this description, but it didn’t take long to find what appeared to be the correct person. Minnie T. (for Thomas or Tucker?) McLellan died June 4, 1998, in Winter Harbor, Maine. Her date of birth was given as February 16, 1903. The Provincial Archives had given Minnie Tucker’s date of birth as February 16, but in 1902. Then I searched the death records in the Maine State Archives and found her there, too, as Minnie Thomas McLellan. That clinched it. So I immediately requested her obituary from the library in Winter Harbor. I was delighted to learn that she had lived to be 95 or 96.

I did one more thing. I searched for her brother, Burton Tucker, at NewspaperArchive.com, and found the following in the June 12, 1948 edition of a New Hampshire newspaper:

A few more clicks on the computer, and I found a Raymond Tucker, who currently lives in New Hampshire. He was the right age. So I called him, excited by the prospect of telling him about a 99-year-old photograph of his aunt.

Mr. Tucker was not home, so I tried again the next day. Still no answer, so I left a message. These events were repeated several more times, until I finally printed copies of the photos and put them in the mail to him, along with a letter of explanation. I mentioned that I discovered that Minnie had died in Winter Harbor in 1998, and that I had requested her obituary. Several days later, the obituary arrived. The first paragraph was a disappointment. She was not the same Minnie.

“Minnie Thomas (Young) McClellan died at a local health-care facility June 4, 1998. She was born Feb. 16, 1903, at Winter Harbor, the daughter of Fred and Ethel (Hammond) Young.”

Imagine that, I thought. Both Minnies were born in Maine on February 16, only one year apart, but they were different people. That made me all the more anxious to hear from Raymond Tucker. It appeared he was my last link to Minnie. But several weeks went by, and I still didn’t hear from him. I tried calling him several more times, but came up empty. Then I went on a short vacation.

When I got home, a surprise was waiting to greet me, a phone message from Mr. Tucker. He apologized and said he had been taking care of some important business and hadn’t had an opportunity to call. He assured me that he was Minnie’s nephew, and that he was very happy to see the photos. He told me that Minnie died in New Hampshire on October 31, 1982. I interviewed him several weeks later and he revealed a big surprise; Minnie’s parents were not Gilbert and Emeline Tucker. He also told me that Minnie had given birth to two children: Kenneth Kierstead in 1926, by an unmarried father known to him only as Mr. Kierstead, and a daughter by Vaughn French, who was born in 1931, but died shortly after.

Edited interview with Raymond Tucker (RT), nephew of Minnie Thomas. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on July 20, 2010.

JM: When were you born?

RT: I was born in 1940, in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

JM: My records show that Minnie’s parents were Gilbert and Emeline Tucker.

RT: I want to be sure I get this right. My wife and I have discussed it a little bit, because it gets confusing. My understanding is that Minnie’s mother was Elizabeth Thomas, who was also the mother of my father, Burton Tucker. But my father and Minnie had different fathers.

JM: Who were they?

RT: I don’t know. All I know is that Emeline Tucker was Elizabeth’s sister, and Gilbert Tucker was Emeline’s husband. When Minnie and my father were born, Elizabeth wasn’t married. Back in those days, there was much more of a stigma attached to having a child out of wedlock. It ended up that Emeline and Gilbert took in Elizabeth’s children.

JM: The Canadian records show that Emeline and Gilbert married in 1894, and in 1895, they had their first child, Cecil.

RT: That’s correct.

JM: In the 1901 Canada census, they also have a daughter named Evaline, or possibly Evelyn.

RT: It was spelled Evelyn.

JM: In 1902, Minnie was born. The Canada birth record lists the parents as Gilbert and Emeline.

RT: That’s incorrect.

JM: I am guessing that when Elizabeth gave birth, Gilbert and Emeline immediately registered Minnie as their child, and the government accepted it.

RT: Yes, that’s apparently what happened.

JM: If that’s the case, then Elizabeth would have been perceived, incorrectly, as Minnie’s aunt. But it was Emeline who was really her aunt. I wonder if Minnie would have referred to Elizabeth as her aunt, or if she knew that she was really her mother.

RT: I know that my father knew all about this. So I assume that Minnie knew it, too. But at what point she became aware of it, I don’t know.

JM: Emeline also had a sister named Millie. In the caption of one of the Hine photos, he said that Minnie lived with her aunt in Grand Manan in the winter. My records indicate that Millie Thomas was that aunt. Millie died in 1921, at the age of 31.

RT: The name rings a bell, but I know very little about her.

JM: My records show that your Aunt Minnie married Vaughn French.

RT: Yes, on September 27, 1936.

JM: Did Minnie have any children?

RT: Our information is that Minnie had a son, Kenneth Kierstead, before she married Vaughn. She gave him the last name of the father, but she never married him. I don’t know what his first name was. Kenneth died on Nov 10, 1974. According to his obituary, he was born in North Head (in Grand Manan) in April of 1926. He had two children, Reid and Lynne, but I lost contact with them quite a while ago, and I don’t know how to get in touch with them. The last I knew, they were living in Back Bay (New Brunswick).

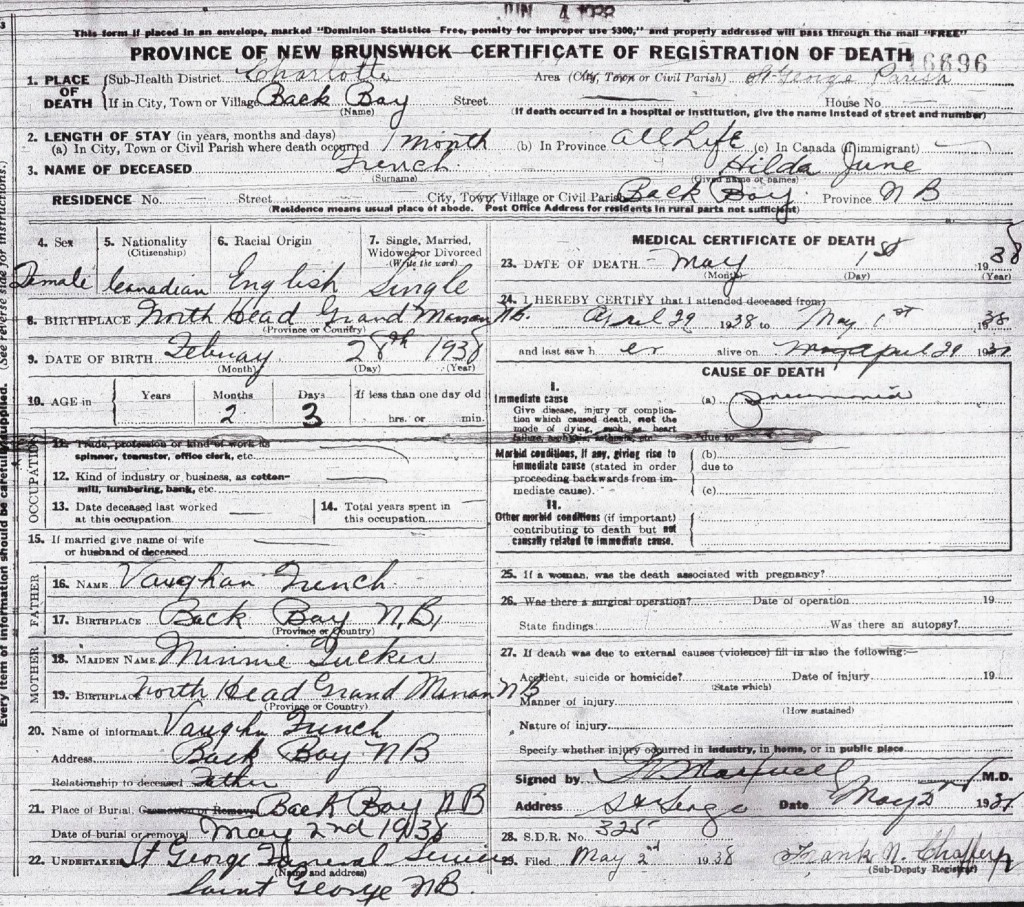

Apparently, Minnie and Vaughn had one child together, Hilda June French, but she only lived for about two months. My records say that she was born February 28, 1931, and passed away on April 30, 1931. That was five years before they married.

JM: Did both Minnie and Vaughn raise Kenneth?

RT: Oh, yes. Minnie and Vaughn lived most of their married life in Back Bay, which is a small seaside town just outside of St. George. That whole community was a factory town. Connors Brothers, the cannery owners, built and developed the town. They built the homes for their employees, and they remained company owned. You worked off and on, depending how well the fishing was going. Minnie worked in the factory. Vaughn worked there, too, I think in maintenance work and in supplies. He might have been a foreman. Back then, most of the line people, packing and canning, were women.

JM: How often did you see Minnie?

RT: Not very often. My first recollection of her was when I was maybe eight or nine years old. My sister and I would go up to the islands with my parents about once a year. We would stay for about a week. But when we went up there, we didn’t always have the time to go to Back Bay to visit Minnie. When we did see her, we might stay for one night, but it was a short visit.

JM: When was the last time you saw her?

RT: That would have been the year she passed away. She was staying with my parents in New Durham (New Hampshire) when she died. That was in 1982. It was quite sudden. She had a heart attack.

JM: What was she like?

RT: Well, my wife remembers that she was a meticulous housekeeper. I found her a little distant and reserved. She didn’t warm up to you easily. But once you got to know her better, she would be comfortable with you. I think that might have been because of her hard life. Vaughn was a lot different from Minnie. He was friendly and outgoing. He was kind of upbeat about things. But both of them always wanted to make you welcome in their home. Minnie was a lot like a lot of people who lived up there. People on the islands didn’t seem to be very joyous and outgoing. And it was a tight community. I got to know a number of people up there very well. Some of them became good friends. But I recognized that if you’re not a native, it’s just different.

JM: What do you think of the photographs of your Aunt Minnie?

RT: To see her at that age was really an eye opener. I couldn’t help be taken by the big knife, and the rough life and working situation that she would have had to deal with. I had heard some stories from my father about how hard it was back then, and how hard everybody had to work to make ends meet. I knew that children back then had to do lots of chores for the family, but to also be working in a factory; I never imagined that.

**************************

Immediately following the interview, I was determined to do two things: find out the first name of Mr. Kierstead, the father of Minnie’s first child, and contact Kenneth’s children, who would be Minnie’s grandchildren. I searched the New Brunswick white pages for Reid Kierstead, but found nothing. In the interview, Mr. Tucker had given me Lynne’s first name, but not her last name. So I went back to the white pages and looked up Lynne Kierstead, but there was no listing. So I tried a long shot. I searched for Kenneth Kierstead on RootsWeb.com, a popular genealogy site, and came up with the following on their reader inquiry page:

“I am looking for info on Basil Kierstead, who lived in Eastport, Maine. He had an illegitimate son, Kenneth Reid Kierstead, who resided in Back Bay, New Brunswick, born April 10, 1926, and died November 10, 1974. Kenneth’s mother was Minnie Pauline Thomas, originally from Grand Manan. -Lynne Hatt”

Contact information for Ms. Hatt was given. I got in touch with her shortly after, and she identified herself as Kenneth’s daughter (Minnie’s granddaughter). I emailed her the photos. She lives in New Brunswick, about 90 minutes from Eastport. Oddly, this happened just a few days before I was to leave for a trip to Eastport to do some research and make a presentation at the local library about the child labor photos taken there. The timing couldn’t have been better. Five days later, I interviewed Ms. Hatt in Eastport, and I learned many new important details about Minnie. Just before I left home for Eastport, I found the death record for Basil Kierstead. He died in Eastport in 1961.

Edited interview with Lynne Hatt (LH), granddaughter of Minnie Thomas. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on August 10, 2010.

JM: What did you think when you saw the pictures?

LH: ‘Oh gosh, that was my grammy!’ We had a sardine factory in my hometown, and my dad worked there. Grammy also worked there, but she didn’t use a knife, she used scissors. So I had never heard of using knives. When I saw the size of my grandmother and the size of the knife, I was amazed. I remember her telling me about working at a cannery when she was a girl. She said that she was short, and they had to build things for them to stand on to reach the table. She said that when the inspectors came, the company would gather all the children and hide them in a room until the inspectors left. She told me also that she would travel from Grand Manan to Eastport to work in the summers.

JM: How old were you when she told you this information?

LH: Probably in my early teens.

JM: How do you react to her telling you this?

LH: I just couldn’t imagine her working at that age, although my father didn’t go any farther than the fourth grade, and then he went to work.

JM: That’s surprising. It was a different era then. He was born in 1926.

LH: I don’t know where he worked. He never told me anything about it. I learned it from my mother. When my father was young, he and Grammy and Vaughn, my step-grandfather, lived in Blacks Harbor. Then they lived in Deer Island. Finally, their house in Deer Island burned down.

JM: When was that?

LH: I have no idea. I don’t know very much about my family’s past. I didn’t know that Vaughn was born in Grand Manan until you told me. I just assumed that he was from Back Bay.

JM: Here is something else you probably don’t know. In 1930, according to the census, Vaughn French was living in Needham, Massachusetts. He was a lodger, and he was working in a cotton mill. He had immigrated to the US in 1925. There were a lot of textile mills in that area, and a lot of people from Maine worked down there in the winter, when the canneries were not operating. When your father was born in 1926, did Minnie have to take care of him all by herself, or did the father (Basil Kierstead) help out?

LH: The father wasn’t in the picture. My father told me that he lived with his grandmother, Emeline Tucker, and Grammy worked. I assume that when she married Vaughn in 1936, my father moved in with them.

JM: My understanding is that Emeline was not the real grandmother.

LH: That’s right, she wasn’t.

JM: Nor was her husband, Gilbert Tucker, the real father.

LH: That’s correct. It’s very confusing. I think it was Raymond Tucker’s mother, Hilda, who explained that to me. Emeline was really Dad’s great-aunt, and Emeline’s sister, Elizabeth Thomas, was Minnie’s real mother. Dad told me who his father was, but that he had never met him. I’m still amazed that Grammy gave Dad his father’s last name, instead of Thomas. I didn’t even realize that Gramma was a Thomas until she died. I thought she was a Tucker. My father and mother were from Grand Manan, and I spent a lot of my childhood there in the summers. That’s when I should have been clued in about the Tucker/Thomas thing. Every once in a while, I’d be talking to some kids in the neighborhood, and someone would say, ‘Oh, you’re Kenneth Tucker’s daughter.’ And I’d say, ‘No, Kierstead, not Tucker.’ I just thought that they were confused. Now I understand.

JM: I found some confusing information about whether Minnie used Thomas or Tucker as her last name. She crossed back and forth to Eastport many times when she was young. In the official border crossing records, she identified her name as Tucker once, and other times as Thomas.

LH: It was confusing with my father’s name, too. One time, my brother Reid went to apply for a passport, because he was thinking about going to England for a vacation. For some reason, they couldn’t find his birth record. They finally found him listed as Reid French, not Kierstead, meaning that my father would have given his last name as French, his stepfather’s name. After Dad died, Mom got new birth certificates for us, both as Kierstead.

JM: What was Minnie’s relationship with Elizabeth, her real mother?

LH: I never heard her or anyone else mention Elizabeth.

JM: Did Minnie have any other children?

LH: Grammy and Vaughn had a daughter, but she died when she was only about three months old, so I’ve heard.

JM: Her name was Hilda June French, according to Raymond Tucker.

LH: That’s right.

JM: Raymond told me she was born in 1931. But Canadian records show that a child named Hilda Jane French was born in 1938, and died the same year. That would have been two years after Minnie and Vaughn got married. I’m almost certain that she was the right Hilda.

LH: Could be.

JM: How close did you live to Minnie most of your life?

LH: We lived very close to her. When Vaughn passed away, she moved in with my mom and dad. Dad passed away the following year, so it must have been very hard on Grammy, losing her husband, and then her son. She lived with my mother for a bit, but it didn’t work out. So she moved in with Uncle Burt (Minnie’s half-brother Burton Tucker) in New Hampshire. She would come back here for a few days about twice a year.

JM: Her death was recorded in St. George instead of New Hampshire. It was not in the New Hampshire death records.

LH: She died in New Hampshire, but she was brought back and buried here. I believe she had a stroke. Her health was good up until then.

JM: When did she stop working?

LH: I think she was about 70.

JM: Was she working at that age out of necessity?

LH: I’m not sure. I don’t think they had any money to fall back on. But they had what they wanted, especially later in life. They had the first color TV in our area. They were comfortable. I think she felt she needed to work. She had worked all her life.

JM: What was Vaughn like?

LH: He was a very kind man. He would do anything for anybody. He was a barber. He had his own barbershop for a while, and had a barber chair in his basement. At the same time, he also worked as a mechanic in the sealing room for Connors Brothers sardine cannery. When he died, he was a manager there.

JM: You said that your father only got as far as the fourth grade? Was that evident? Did he appear uneducated?

LH: No. It always used to amaze me. His writing skills and his spelling weren’t good, but he spoke good English and he had a good knowledge of many things. He was good in math. He could do math better in his head than I can now.

JM: Did he read a lot?

LH: No, but he could read.

JM: Could you carry on a conversation with him about national events and other things?

LH: He was very political. He talked a lot about politics, and worked for the parties.

JM: When did your father die?

LH: He was only 48 when he died. He had some health problems. He was a very hard worker and had a very stressful job, being a manager at that time. He died of a heart attack.

JM: Is your mother still alive?

LH: Yes. She’s 86.

JM: What do you do for a living?

LH: I am sort of retired. I worked a long time in the sardine factory. I did a little bit of everything there over the years. I packed fish, worked in the sealing room, worked in quality control, and worked in the shipping department. When the plant closed, I went to Blacks Harbor and worked in the shipping department of the cannery there.

JM: I see a pattern here. Is there anything else to do in your area other than working in a cannery?

LH: There is now, but not much else before. Of course, there were your basic retail jobs, and teachers and those kinds of professional jobs.

JM: Did you grow up with the idea that you were destined to work in the canneries, just like your father and your grandmother?

LH: Actually, I thought I would go to college after I graduated from high school, but I didn’t know what I wanted to do. So I went to St. John and worked there for a year, but I wasn’t very happy. My dad didn’t think it was a very good idea, and that I should be home. I think he worried about me being in the big city. So I came back. Then I met my husband and we stayed.

JM: What does your husband do?

LH: He’s retired. He worked in a pulp mill. Then he got into commercial fishing, right after we started having children. Now he just likes to fish.

JM: What was Minnie like?

LH: She was a very quiet, private person. She had a stern face, and she didn’t talk much. If you asked her a question, she would tell you a little more. Because she was so quiet, if she suddenly said something funny, we would look at her and say, ‘Grammy, did you really say that?’ She usually said what was on her mind, so she was blunt and straightforward. You knew where you stood with her.

JM: What did you do together?

LH: Not much, truthfully. I don’t remember her ever reading to me. I remember thinking as a child, ‘She never talks.’

JM: Would you talk to her even when she wasn’t responding?

LH: I’m sure I talked on and on. She didn’t ignore me, but she just wouldn’t say much about it. When I gave her a hug, she would hug me, but she was not one to give you a hug voluntarily. Until I was older, I wasn’t close to her.

JM: What changed when you were older?

LH: Well, I grew up, and I could have a conversation with her, because I could talk about things that meant something to her.

JM: How do you think she felt about the fact that she was raised by her aunt, rather than her mother?

LH: That’s a hard question. I think she must have been hurt by it. I think that was one of the reasons she was a tough lady. She was forced to do things on her own. I’m sure that Emeline and Gilbert were good to her, but she knew about her mother when she was growing up. And then she had a baby out of wedlock.

JM: If you could talk to Minnie again, knowing what you know now, what would you want to ask her?

LH: I’d want to know about her childhood even before she went to work. I’d ask her about her work. There’s so much that goes through my mind. It’s been only about five days since I saw the pictures. I’ve had a busy five days, but I’ve been thinking about her all the time. I’ve been around a lot of people, and I think I’ve told everyone of them about it. Most of all, I’d want to know a lot about her feelings about all of this.

JM: Knowing what you know now about the culture and economy of Grand Manan, you must have some idea of what her life might have been like when she was growing up.

LH: I can understand why she had to go to work. People had big families, and they had no money. The kids had to help out if they were to survive.

JM: What do you think their lives would have been like if there had been an effective child labor law in the early 1900s that prevented children from working in Canada and the US?

LH: I guess it wouldn’t have worked very well, because the canneries wouldn’t have had enough workers. But there were still canneries in Grand Manan after child labor ended. They still were the main industry, along with fishing.

JM: Do you eat sardines?

LH: Very rarely.

JM: Did you ever eat them much?

LH: No, because I worked with them all the time.

JM: My wife and I toured the Hershey plant back about 40 years ago, and one of the workers told us that the company let the workers take home all the broken chocolate they wanted. My wife said, ‘That must be great.’ And the worker said, ‘Yea, for about a week. I don’t eat chocolate at all anymore.’ I wonder to what extent cannery workers hated sardines, or if they were a staple of their diet. I wonder if they were tempted to stick a few cans in their pockets when they were working.

LH: They probably did that. They didn’t have a lot of money, so they had to eat what they could afford, and what was available.

JM: Did any of your children know Minnie?

LH: When they were very young. Our youngest barely remembers her.

JM: Did they see the pictures?

LH: Yes. They were appalled to see her in that situation. I’ve got two great-nieces, one seven and one ten. I look at them, and it’s not fathomable that they could go to work.

JM: It happens all the time in South Asia.

LH: Right, but we don’t think about that, because we’re happy in our own little world.

**************************

After transcribing Lynne’s interview, I knew I still had some important details to research. When exactly was Minnie and Vaughn’s daughter born, and when did she die? What happened to Elizabeth Thomas, Minnie’s real mother? I needed Minnie’s death certificate and obituary, and I wanted a photo of her gravestone. Finally, I wanted to see her official her birth certificate. Would it clear up the question regarding whether she was named Tucker or Thomas, and would her real mother be mentioned?

I found Elizabeth in the Canada census, up through 1901. She was listed as Lizzie, living in Grand Manan with her father and two sisters. She was born in 1881. I searched the New Brunswick marriage records for her (both Elizabeth and Lizzie), and found one possibility: an Elizabeth Thomas had married Albion Moffitt in Grand Manan on October 23, 1907. Birth records showed that they had two children, and death records showed that Elizabeth Moffitt died on June 12, 1956. The only way to see if she was really the correct Elizabeth was to obtain her death certificate, so I could see what her parents’ names were.

I asked Lynne Hatt to send me a photo of Minnie’s and Vaughn’s gravestones, and she quickly obliged. And it didn’t take me long to obtain Minnie’s death certificate, obituary and birth certificate, which hadn’t been officially certified until 1954. Tucker had been noticeably corrected to Thomas, and Gilbert Tucker had been crossed out as the father. But Emeline was still listed as the mother, with no mention of Elizabeth.

I emailed the archivist at the records center about this.

“I have a question. The family said that Minnie was born to Elizabeth Thomas, the unmarried sister of Emeline Thomas Tucker, but Emeline and her husband Gilbert immediately became the custodians for Minnie, and they raised her. Somehow, the Tuckers were able to register Minnie’s birth and claim, incorrectly, that they were the parents. That may be why there are some changes in the birth certificate.”

He replied:

“That explains it. I suppose that since her birth was not registered until 1954, nobody asked any questions. Maybe no one was left who knew who her father was. These mysteries are interesting, but terribly frustrating.”

I also received Hilda’s death certificate. Hilda June French, daughter of Minnie and Vaughn French, was born on February 28, 1938, and died on May 1, 1938. (Note that Vaughn was the informant, and he listed Minnie’s maiden name as Tucker.) Several days later, Elizabeth’s death certificate arrived in the mail. It was a disappointment. She was not Emeline’s sister and Minnie’s mother. It appears that we will never know what happened to Elizabeth.

The search is over, and it’s a good time to review the important details of Minnie’s life.

Minnie Pauline Thomas was born in Grand Manan, New Brunswick on February 16, 1902. Her mother was Elizabeth Thomas, who gave birth to her out of wedlock. Her father is not known. She was raised by Elizabeth’s sister Emeline Tucker, and her husband Gilbert Tucker. Minnie usually spent much of the warmer months with Emeline and Gilbert in Eastport, while they worked in the canneries, and the winter in Grand Manan with her Aunt Millie Thomas. By the time she was nine, she was already working in the canneries.

In 1926, she gave birth to Kenneth Kierstead. The unmarried father was Basil Kierstead, who apparently had no further contact with Minnie. Ten years later, Minnie married Grand Manan native Vaughn Harley French and eventually settled in Back Bay, New Brunswick. Their only child, Hilda June French, was born in 1938 and died several months later. Vaughn died in 1973, at the age of 68. Minnie died in 1982, at the age of 80.

*Story published in 2011.