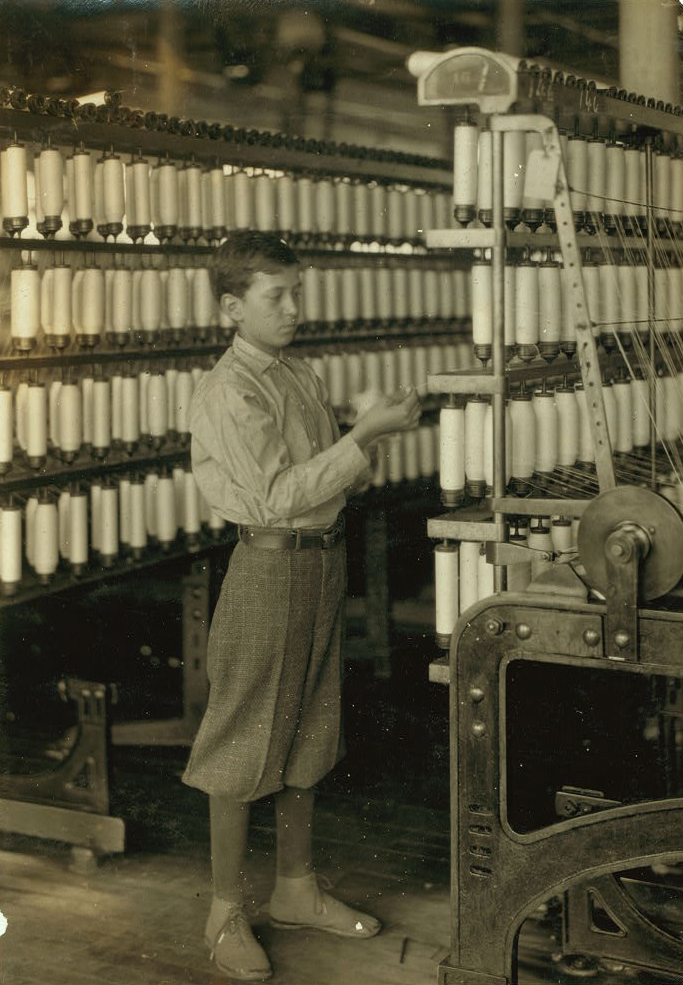

Lewis Hine caption: Back boy – 14 years old – Mule room. Berkshire Cotton Mills. Location: Adams, Massachusetts, July 10, 1916.

“In our family, the boys all had to start working at 14 years old, to help out. My first pay was $3.70 for a 48-hour week, and I would get 50 cents allowance.” -the late Sylva Marcil, from a brief family history he wrote when he was about 65 years old

“My dad loved the outdoors. I imagine that came from having to be cooped up in the mills all the time. He used to hike up Mount Greylock. He would round up me and all the neighborhood kids on Columbus Day, and take us up the Cheshire Harbor Trail. He made sure we always had our walking sticks, a paper bag lunch and a bottle of water. He would get us in a line, and like in the Army, he would give us an inspection to make sure we were all set.” -Claudette Marcil, daughter of Sylva Marcil

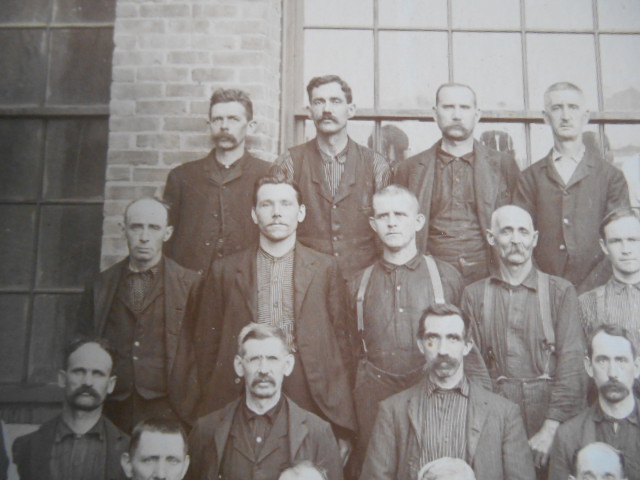

Lewis Hine visited Adams twice, once in 1911, taking pictures outside of the mills of the massive Berkshire Cotton Manufacturing Company, immediately following a similar visit to the Eclipse Mill in neighboring North Adams. In both cases, he documented children working under the age of 14, which was the minimum age at that time for child workers in factories in Massachusetts.

Lewis Hine photo: Back boy – 14 years old – Mule room. Berkshire Cotton Mills. Location: Adams, Massachusetts, July 10, 1916.

Hine returned to Adams in 1916. His assignment was to find out if a new Massachusetts child labor law that took effect in January of that year was being complied with and enforced. On the very day Hine photographed Sylva Marcil, July 10, the following was published in the Lowell Sun (Mass.)

“The present year has smashed Lowell’s record for employment certificates all to pieces, the total number issued thus far being 710. This number includes 438 employment certificates to children between 14 and 16 years of age who have never worked before and 272 educational certificates to 272 minors between the ages of 16 and 21.”

“There’s another new law that is quite important and of much interest to employment seekers. It has to do with the employment of certain minors in the summer. Heretofore it was not allowable to employ children who were over 14 but under 16 years of age, and who did not possess ability to read, write and spell the English language, at any time of the year, or at any stage of the game, but the law has been amended to read that they may be granted an employment certificate good for the summer vacation.”

*Note: The law also specified that children who were 14 or 15 years old must show that they had attained at least a fourth-grade education.

Also in 1916, the federal government passed the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act, which had restrictions that were substantially the same. Two years later, the law was declared unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court, but the ruling did not affect the Massachusetts law.

Hine took 18 pictures that day, all inside the mills, He appeared to confirm that the new law was working, which was the obvious reason why the owner gave him permission to take his camera inside. Some of the children, including Sylva, were noticeably “dressed up” in clothing not typical for mill workers, indicating that the owner was quite prepared for the visit from Mr. Hine. But Hine did not give the names of any of his subjects in his captions, perhaps at the request of the owner.

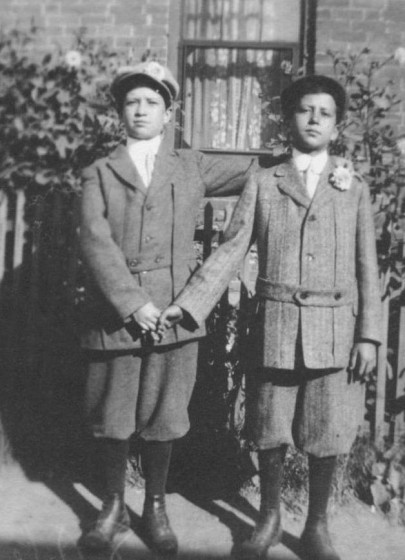

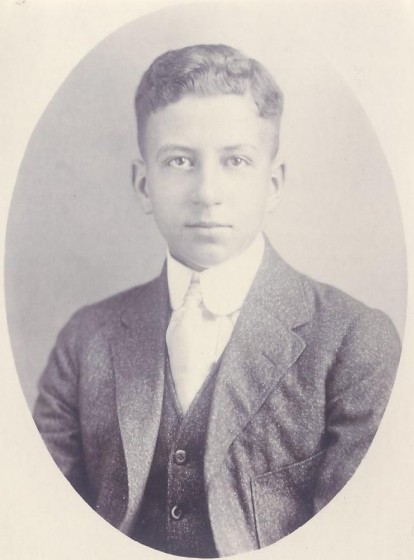

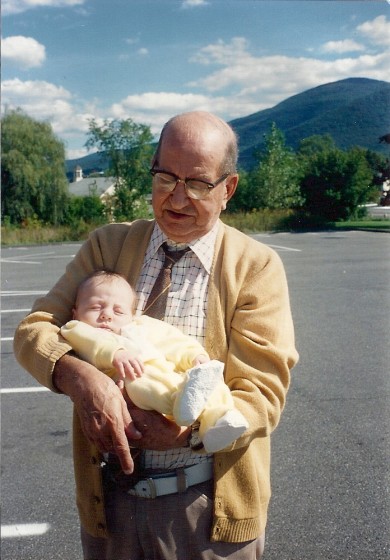

Sylva was eventually identified in three of the pictures, two of them almost identical. Because he was not identified by Hine, there had to be a way to publicize the pictures, in hopes that someone would recognize him. Eugene Michalenko, president of the Adams Historical Society, posted them on the society’s website, which caught the eye of Adams resident Claudette Marcil, Sylva’s daughter. I contacted her, and she provided me with photos of her father, which confirmed that the boy was, indeed, Sylva.

The two photos below, taken the same year, one by Hine and the other taken by the Marcil family, positively identify the boy in the Hine photo as Sylva Marcil. All photos provided by the Marcil family, except where noted.

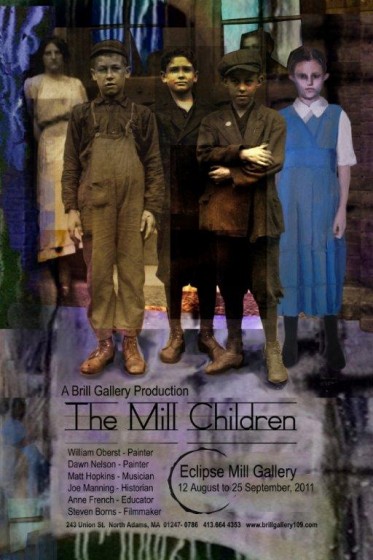

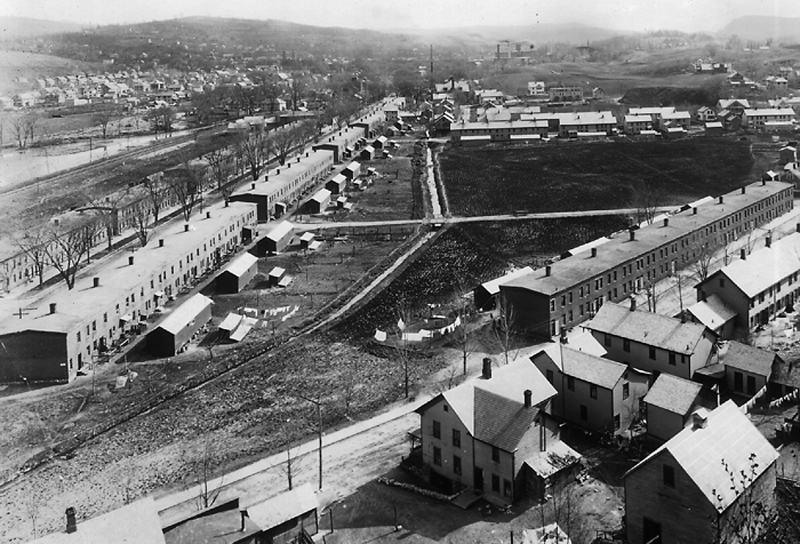

This story is the result of the decision to install an exhibit, called the Mill Children, in one of the surviving buildings built and occupied by the former Berkshire Cotton Manufacturing Company, which opened its doors in 1889, and remained in Adams until 1958. The building, later occupied by the Waverly Mill, is undergoing renovations.

The Mill Children exhibit, created by North Adams artist Ralph Brill in 2011, opened at the Eclipse Mill in North Adams on the 100th anniversary of Lewis Hine’s visit to that mill in August of 1911. The exhibition included my stories about some of the child laborers that were photographed at the mill, related work by several visual artists, as well as contributions by an educator, a documentary filmmaker and a music composer. Since then, the exhibit has traveled to other Massachusetts cities, as well as to Bennington, Vermont.

I was asked to research the Hine photos in Adams, and to try to track down stories of some of the children, so we could add them to the exhibit. Both the Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield), and the Adams Historical Society agreed to publicize the photos. And that is how I came to identify Sylva Marcil.

Sylva Marcil was born in Montreal, Canada, on September 9, 1901. According to official records, his baptismal name was Joseph Harmisdas Sylva Marcil. He was the youngest of six children born to Mathias and Oveline Marcil. Two of the children died young, at ages one and four. According to family records, Mathias was born in Montreal on February 23, 1863. He and his parents immigrated to Springfield, Massachusetts (probably in the 1880s), where Mathias met Olevine Paquin, who was born in Agawam, Massachusetts, on May 29, 1873. They married on November 22, 1892, in Montreal, where all of their children were born.

In 1903, Mathias, Olevine, their four surviving children (Lawrence, Joseph, Antonio and Sylva), returned to the US, and moved into an apartment at 19 Albert Street, in Adams, very near the Renfrew Manufacturing Company mill off Columbia Street, where Mathias got a job.

Two years later, Renfrew completed construction of a number of brick row houses on Columbia Street for their workers. That year the Marcil family moved into an apartment at one of those row houses, at 176 Columbia Street.

In the early 1900s, Adams was experiencing tremendous growth, due to the expansion of the Renfrew mills (established in 1868), and the Berkshire Cotton Manufacturing Company, which had erected four large mills by the first decade of the 1900s, and would become the largest employer in Adams for 60 years. From 1900 to 1925, the population swelled with immigrants, mostly Polish and French Canadian. Business increased substantially in the commercial district on Park Street, churches went up, and new schools were built.

Sylva started working (legally) at the Berkshire Mills in 1915, when he was 14 years old, a year before the new state child labor law took effect. According to the Hine photos, he worked in the mule room, which meant that he was operating a mule, a machine which spun cotton into thread. It would have been a busy and tedious job.

From 1920 to 1921, Sylva served in the Army. In 1921, he married Aurore Sweeney (originally Choiniere), of Adams, and they moved into 174 Columbia Street, the apartment next to that of his parents. They had two children, Oliver in 1922, and Claudette in 1940. During World War II, Oliver served three years in the Army Air Corps, after which he was a letter carrier for the Adams Post Office for 30 years. He passed away in 1983.

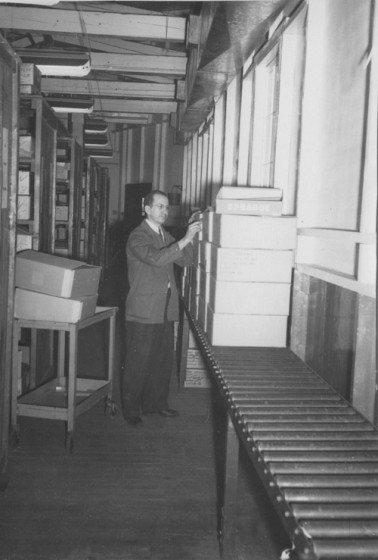

Sylva and Aurore lived the rest of their lives in the house. In 1927, Renfrew declared bankruptcy and sold the mill houses to Salem “Sam” George; and in 1949, Sylva and his parents each bought their apartments from Mr. George. Sylva worked in the Berkshire Mills for 30 years, and then 14 years for the Sprague Electric Company in North Adams. Aurore passed away in 1983, and Sylva passed away four years later. They were married for 62 years.

Edited interview with Claudette Marcil, daughter of Sylva Marcil; and Eugene Marcil, nephew of Sylva Marcil. Eugene’s father Joseph was Sylva’s brother. Interview conducted by Joe Manning on May 16, 2014.

Manning: Claudette, when were you born, and where were your parents living at that time?

Claudette: I was born on April 13, 1940. My parents were renting an apartment at 174 Columbia Street, in the row housing owned by the Renfrew mills. They were eventually sold to Sam George. My father later bought his place from Sam (in 1949), and his father and his brother Joseph bought their places as well.

My father’s parents, Mathias and Oveline Marcil, lived next door at 176. Mathias was born in Montreal, came to America, married Oveline, who was from Springfield, Massachusetts, and then returned to Montreal. After their children were born (four boys), including my father, who was born September 9, 1901, they moved to Adams, in 1903, where my grandfather worked at the Renfrew mill.

Every other year, before I came along, my father and the whole family would go to Canada and visit their cousins and have big get-togethers. On the other years, the relatives would come down here.

My parents had two children, me and my brother Oliver, who was born in 1922, so he was 18 years older than me. My father worked in most of the Berkshire Mills buildings (the company was officially called Berkshire Fine Spinning starting in 1929). He probably worked the night shift before I was born. When I was young, he worked 3:00 to 11:00 pm. I remember having to be quiet in the morning so he could sleep late. He was an assistant foreman for his last 15 years there.

Claudette: In 1946, he went to work for Sprague’s (Sprague Electric Company in North Adams), where he worked the day shift in the retail sales department. He worked there 18 years, and retired in 1964, at the age of 62. He worked a total of 50 years.

He and his three brothers were all hard workers. They were all quite regimented. They kept to a schedule. When he worked at Sprague’s, he would go to work, come home, have supper, read the newspaper, and that was about it.

Eugene: All four of the brothers kept journals, from about 1920 to 1943. They wrote down everything they did, even little items like what they bought their kids for Christmas each year. My father would get up at 5:00 in the morning and write down his plans for the day on index cards. And it was all work. But on weekends, they found time to do their picnicking in the area.

Claudette: My dad loved the outdoors. He loved the fresh air. I imagine that came from having to be cooped up in the mills all the time. He loved hiking. He used to hike up Mount Greylock. He would round up me and all the neighborhood kids on Columbus Day, and take us up the Cheshire Harbor Trail. I often wonder if that was how the Greylock Ramble got started (Columbus Day tradition when thousands of people walk up Mount Greylock). He made sure we always had our walking sticks, a paper bag lunch and a bottle of water. He would get us in a line, and like in the Army, he would give us an inspection to make sure we were all set. Nobody under eight years old could climb the mountain. So there were a lot of little kids in the area that were just dying to be eight so they could go.

He and his three brothers all lived in the block. In the 1920s and 1930s, they all raised chickens. My father’s coop became my brother’s club house when he was a teenager. When he went off to war, it became my play house.

We loved living in the block. Families could keep to themselves when they wanted, but we could get together in the back yard when we wanted to. The kids would run around the neighborhood and play marbles and all those outside games. And we had Renfrew Field right behind us. We were always out there playing baseball and basketball and climbing on the monkey bars, and we had ice skating in the winter. When I was a teen, I used go the McKinley Square and get ice cream with the other kids after school. All the girls wore charcoal gray blazers ̶ a fad in the 1950s ̶ and Scottish plaid skirts and bobby sox.

Manning: Did you go to the Catholic schools.

Claudette: No, but my father did. I went to Renfrew School, and graduated from Adams Memorial.

Manning: Did your parents speak French?

Claudette: They would if they wanted to keep secrets from us.

Manning: Did your mother work outside of the home?

Claudette: She worked in the mills for a couple of years before she got married. She probably met my dad in the mills.

Manning: When you were growing up, did your family go on vacations?

Claudette: Not really.

Manning: Did your parents have a car?

Claudette: No. I got married in 1959, when I was 19, and that’s when they finally got their car. We walked everywhere. We did most of our shopping right here in Adams. Every other Saturday, my parents and I would get on the bus and go to North Adams. We’d go down to Eagle Street, eat lunch at Jack’s Hot Dogs, and then browse in the shops on Main Street. My dad loved to buy us nice clothes. We’d go to the Boston Store, and he would sit in a chair watch my mother try on clothes, but it was always his choice. After that, we’d see a movie at the Paramount. On the other Saturdays, we’d stay home and do all the housework and the outside work.

Manning: What chores did you have to do?

Claudette: Oh, wash the dishes and clean my room, not much. I was spoiled a little. I had it kind of easy. My dad had to work awfully hard when he was young, and he didn’t want me to have to do the same thing. He and his brothers never really had a childhood. They were old by the time they were 16.

Manning: Did you go to college?

Claudette: No, and my brother didn’t either.

Manning: Was your father strict?

Claudette: Yes. My father was definitely the head of the household. But I respected him for that. He demanded respect.

Manning: Are you like your father?

Claudette: I’m more relaxed than he was. I’m not rigid. He always had a plan and a time schedule, and I take things as they come along. My mother was mild mannered, very pleasant, easy going.

Claudette: My father wasn’t raised to show his emotions, but he was still a wonderful father. He taught me how to ride my bike. I loved watching him on the fall hikes. He always had his baseball cap on, and was smoking his pipe or cigar. I remember him getting up on the ladder every fall to put in the storm windows. He used to take me to the Williams College football games. We’d take the bus. He would root hard and try to get me excited about it. He would explain things to me, but I wasn’t really interested much in sports. He also listened to the Red Sox games on the radio.

He used to take me on long walks up Notch Road. We’d sit on a big rock overlooking Adams. Every fall, we’d pull my wagon up to Jaeschke’s Apple Orchards for a bushel basket of apples. He’d let me work out in the shed with him, pounding nails and sawing boards. We’d walk all the way up to Park Street Hardware when he needed nails and small items, and I’d get my own little bag of brand new nails. I felt so big.

In 1964 when he retired, he and my mom traveled the following 18 years, mostly to Montreal. He had worked steadily for 49 years, and he deserved it all.

Manning: When were you born, Eugene?

Eugene: May 8, 1936. I remember that my father’s parents spoke French. Every New Year’s Day, we’d have to go visit them and wish them a Happy New Year. We had to say it in French, so we would always rehearse while we were walking down to their apartment. When we said it, they would glow.

Manning: Did you work in the mills?

Eugene: No. When I was 15, I started at the Paradise Electric Shop in Adams. Val’s Variety is there now. I got my work certificate from school, and I worked after school hours and on weekends. After I graduated, I worked about 12 more years at the shop. And then in 1964, I took over the business, and worked for myself until 1994.

Manning: Claudette, when did your father die?

Claudette: September 22, 1987. He was 86 years old.

Manning: Was he in good health most of his life?

Claudette: Right up until June that year. He had been mowing the lawn with his old push mower, and he suddenly got very sick. I was living and working in New Hampshire when it happened. He never had anything to do with doctors or hospitals. He called me and said that it was a good time for me to come home. I could tell that there was something terribly wrong. I gave up my job and moved back. I took care of him until he died a month later of congestive heart failure. My mother had died four years earlier. So I took over the house.

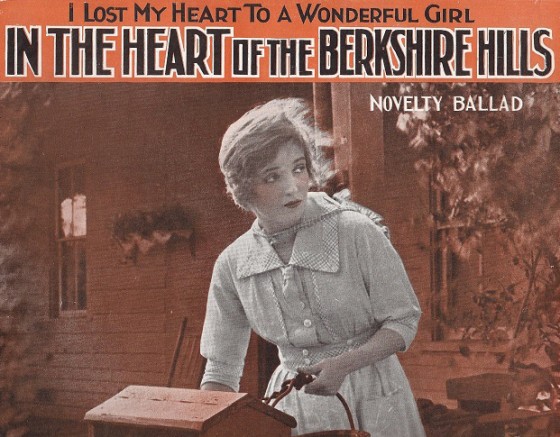

Eugene: Uncle Sylva played the piano, and his brother Antonio played the violin.

Joe: Could they read music?

Claudette: I guess they could, because I still have some of the sheet music they used.

*Story published in 2014.