“Eddie Lou looks exactly like I would have expected her to look at that age. I love that little smile on her face. When I saw that, I cried. She was one of the happiest people I ever knew. She was also very talkative. She could tell you so many tales and stories that could keep you entertained for hours.” -Sue Parker, daughter-in-law of Eddie Lou Young

Eddie Lou Young was born on August 28, 1900. She lived at the orphan home for about year. In the spring of 1910, Reese and Luella Parker, who had a farm near Americus, were looking to adopt a child. They had married in 1898, but lost their only two children in infancy. According to daughter-in-law Sue Parker, Eddie Lou proved irresistible to Mr. Parker when he and his wife showed up at the Methodist Home. She was nine years old when she left with the Parkers.

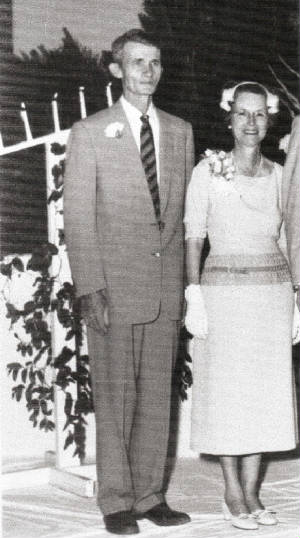

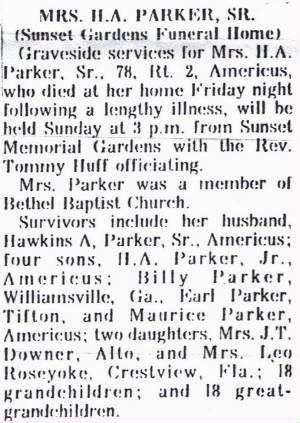

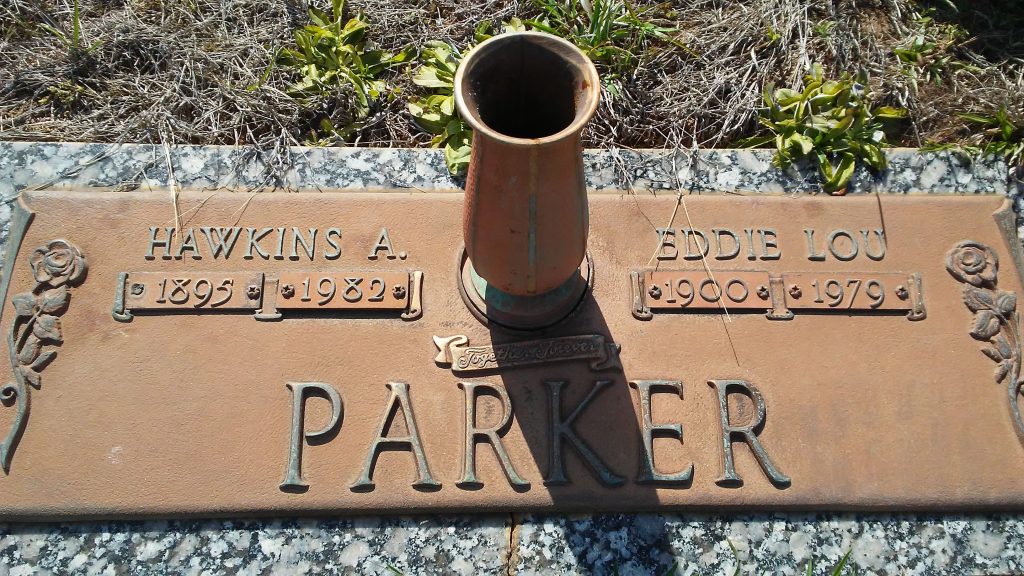

Eddie Lou married Hawkins Alexander Parker on August 28, 1920, at the Salem Methodist Parsonage near Americus. Hawkins was related to Eddie Lou’s adoptive father. He was a carpenter and building contractor. They had seven children: Maurice, Earl, Thelma, Hawkins Jr., James (who was killed in World War II), Anthony William (called Billy), and Ella Elizabeth (called Betty). They moved to Plains about 1941, and for a time, lived several houses away from a young married couple named Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter. She died on August 10, 1979, three weeks before her 79th birthday. Her husband Hawkins died in 1982.

I interviewed her son Earl Parker. Ironically, he lives in Tifton, although he never knew his mother lived there. I also interviewed Sue Parker, who is the widow of Eddie Lou’s son Maurice.

Edited interview with Earl Parker (EP), son of Eddie Lou Young. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on February 16, 2011.

EP: I thought the pictures were great. I have a picture of me and my sister when I was six and she was four. Both of us have long hair, and you can see the resemblance to my mother. My mother never did tell me that she worked in a cotton mill, but I knew that her sisters and her mother did. I didn’t know that they moved from a farm to Tifton.

JM: Did your mother tell you much about her life when she was young?

EP: Not much, but she said that the neighborhood she lived in was poor. She talked about kids carrying knives and that kind of thing. She never did tell me much about her life before she lived with the people I called my grandparents, Reese Parker and Laura Luella Bray Parker, the couple who adopted her.

JM: When were you born?

EP: 1933.

JM: Where were your parents living at the time you were born?

EP: In Sumter County, out away from any of the towns. We lived on a farm in what was called the old 28th District, west of Americus.

JM: Did they own the farm?

EP: No, they didn’t. My father was a carpenter. When the Depression came and he couldn’t get a job, he depended on the farm just to make a living. His father had been a farmer. His father had been fairly wealthy, but he died when my father was about five years old. By the time my father was of age, there wasn’t much money left. The family had used it up.

JM: Did your mother keep in touch with any of her brothers and sisters?

EP: Not really. I never heard her say anything much about them. I guess she just wanted to forget about that part of her life. She knew that she had some sisters in Albany. Every now and then, somebody from Albany would stop by to see her, but she really didn’t try to keep in touch. Her real mother, Mrs. Young, came to our house and visited for about a week when I was about eight years old. But I was never encouraged to call her my grandmother. To me, my mother had this feeling that she was given away, that her mother didn’t want her. She didn’t have much to do with her mother after that.

JM: When Mrs. Young died, did your mother go to the funeral?

EP: As far as I know, she did not.

JM: Did she talk about going to an orphanage and being adopted?

EP: She just said that she didn’t stay very long. I was one of the youngest kids, so she might have already explained some of those things to my brothers and sisters. And I never knew enough to ask questions.

JM: How many children did your parents have?

EP: There were seven of us. My brother and I are the only ones left.

JM: What was your mother like?

EP: She was very outgoing. But she never liked to travel very much. We moved to Plains when I was about eight years old, and she did not even care much for going back to the house where she grew up. Her mother, Mrs. Parker, lived in the country outside of Americus, but my mother seldom went back to see her. She was very outgoing when it came to her neighbors, but she just didn’t want to leave town. She lived in Plains the rest of her life. They lived on Water Street, but there were no house numbers then. The house is still there, but the street name has changed.

JM: Did you have a car?

EP: Yes. My father always had a car. When he was young, his older brothers had a car. He told me that one time they were somewhere, and his brothers got inebriated and they had him drive home. The only problem was, he didn’t know how to stop it. So what he did was to turn it around in the yard, and the car finally stopped just before it hit the barn.

JM: When you lived in Plains, was your father still a carpenter?

EP: Yes. He and a friend of his had a building business, and they operated out of Americus.

JM: Did your mother ever work outside of the home?

EP: Never did.

JM: Because you lived in Plains, I am wondering if your family knew Jimmy Carter.

EP: Oh, sure. His father wrote the first letter of recommendation that I ever got, for a job I had applied for. If you lived in Plains, you knew everybody. Jimmy is about 10 years older than me. We were not close friends. His younger brother, Billy, was closer to my age, so we knew each other better. We played together when we were kids.

JM: Did your mother know Jimmy?

EP: Yes, she knew him. I’ll tell you this little story. One time, somebody was asking Jimmy about me, and one of the things he said was that he remembered that my mother dipped snuff. I don’t know what else he told them about her. He would probably still remember the family. I knew Jimmy’s mother fairly well. She was a nurse.

JM: Was your mother a hard worker?

EP: Yes, but there’s a little bit of a twist here. Most of my life, my father provided my mother a wash woman to wash the clothes, and a maid to come in and clean the house. So my mother did not have those two things to do. She just had to look after the kids and cook the meals.

JM: How could your father afford it?

EP: He made enough money in his business to do it. We weren’t wealthy, but we had enough.

JM: How far did your mother get in school?

EP: I’m not sure, maybe till about the seventh grade. She quit school, which was not too unusual then. She had gone to the New Era School near Americus. Her father, Mr. Parker, and some other fathers in the neighborhood, provided the land, built the school, and provided a wagon to carry the children to school. My father went to school until he was about in the eighth grade, and then his mother passed away, and that was the end of that.

JM: When did your parents get married?

EP: In 1920, on August 28, right before my mother’s 20th birthday. My oldest brother, Hawkins, was born a year later.

JM: Was your mother in good health all her life?

EP: Yes, I’d say she was. She was a slender, small woman, and had a bit of a back problem and some arthritis in her later years. And then she had cancer. She died in August of 1979, shortly before her 79th birthday. My father died in November of 1982.

JM: Did you ever meet any of her brothers and sisters? Do you remember anything about them?

EP: My mother saw Alex quite a bit after she got married. He lived a long time in Macon. Once in a while, he would come and spend two or three days with us. He worked for the federal government most of his life. He worked at the air base in Warner Robins back in the early days when the base began (during World War II). From there, he went to Japan and spent several years working for the federal government there. He lived with a Japanese woman there, and I think he might have married her in Japan. But when he left Japan, she didn’t come back with him. After he returned to the US, about 1956, he lived with my parents off and on for three or four years.

Elzy was in World War I, and died of pneumonia. My mother mentioned him every once in a while. She told me that Elzy was one of her favorites. Seaborn and Jesse were adopted by the same family. Seaborn came to see my mother once. That was in March of 1962. I don’t think he was in good health at the time. One of her sisters, I don’t remember which one, married a man named Williams, and she lived in Waynesboro.

JM: That was Mary. She married Sam Williams.

EP: One of their boys stopped by Plains to see my mother once, after his family found out she was living there. When I was working in Augusta in the summer of 1952, the Williams family lived near there, in Waynesboro, so I dropped by their house and met some of them. But after that, we didn’t keep in contact.

JM: Did you go to college?

EP: Yes. I got a PhD in botany. I was the only child in the family to get a college degree. When I graduated from high school, I had no idea what I wanted to do. I had a teacher at the high school named Julia Coleman. She was Jimmy Carter’s high school English teacher. She encouraged me to look into a vocational rehab scholarship, because it could pay my tuition so I could go to college. My parents told me that if I wanted to go to college, they would help me out. So that’s what I did. After I got a bachelor’s degree in education at Georgia Southern University in Statesboro, I went into teaching, but I realized right away that teachers needed to know a lot more than I did. So I got some more scholarships and went back and got a master’s degree in education, also at Georgia Southern. After I got that, I found out that I needed to get even more education, so I got in touch with a professor at the University of Georgia. I had also been in the military, and I had two years left on the GI Bill. Three years later, I had a PhD. That was in 1972, and I was 39 years old.

JM: Your mother must have been pretty proud.

EP: Well, her attitude was kind of interesting. When I was growing up, she was determined that all of her children would get at least a high school diploma. And they all did. But she never mentioned college. Back in those days, if you had a high school diploma, you had no problem getting a job. So when I got my PhD, her reaction was like, ‘You mean you’re still going to school?’

JM: In the picture of your mother with the other girl, I love the way she is smiling. She was very beautiful.

EP: I noticed right away that they were standing in front of a spinning machine. The thing that’s interesting about that is that she never thought much of cotton mill workers. In any kind of conversation about them, she always sort of low-graded the cotton mill workers. She told me they were the kind of people I shouldn’t associate with. I guess she just couldn’t accept that part of her life.

************************

After I talked to Earl Parker, I looked up information about Julia Coleman, Jimmy Carter’s teacher, who later helped Earl get into college. Ironically, Ms. Coleman got her education at Bessie Tift College, which was named after the wife of Henry Harding Tift, owner of Tifton Cotton Mills. Bessie attended the college when it was called Monroe College. In the early 1900s, Mr. Tift donated heavily to the college in order to save it from bankruptcy, leading to the name change in 1907. Thus, the man who illegally employed 8-year-old Eddie Lou Young at his mill also funded the college that enabled Julia Coleman to get an education. She, in turn, assisted Eddie Lou’s son in getting a scholarship so that he could go to college and ultimately get a PhD.

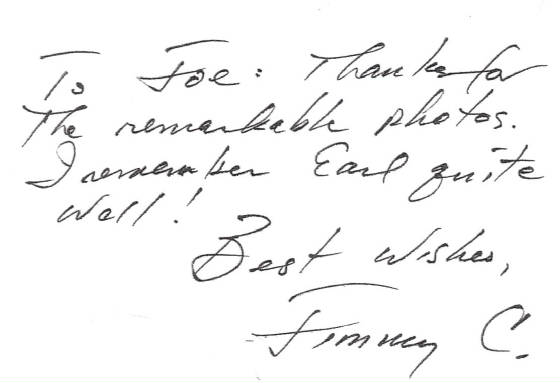

I wrote to former President Carter in care of the Carter Center, and enclosed copies of the pictures of the Young family. I explained the significance of the pictures, and mentioned my interview with Earl. About three weeks later, I received a letter from the Carter Center. When I opened it, all I saw was my letter to Mr. Carter. But then I saw this in the upper right hand corner of the letter.

Edited interview with Sue Parker (SP), daughter-in-law of Eddie Lou Young. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on February 28, 2011.

JM: What did you think of the photos?

SP: They are unbelievable. Eddie Lou looks exactly like I would have expected her to look at that age. I love that little smile on her face. When I saw that, I cried. She was one of the happiest people I ever knew. She was also very talkative. She could tell you so many tales and stories that could keep you entertained for hours.

JM: Did she tell you that she lived in Tifton? And did you know that she worked at a cotton mill when she was a child?

SP: She never mentioned anything about Tifton. She always talked about Ashburn, which is about 20 miles from Tifton. And she never told me that she worked at a mill. I wonder if she blocked it out of her mind. Maybe she was ashamed to talk about it, because some of her children thought she came from a low-class family. Her husband’s family, the Parkers, had been much better off.

JM: Not too long after she was photographed, she went to the orphanage. Did she talk about that?

SP: She just said that her father died and her mother could not take care of the family. I believe that the State of Georgia authorities came in and took the children because of the poor conditions they were living in. That’s what she told me.

JM: In the 1910 census, she is already listed as living with the Parkers, Reese and Luella, her adoptive parents.

SP: It’s my understanding that when Reese Parker first saw her, he immediately fell in love with her. He could’ve adopted a boy, who could’ve helped on his farm, but instead, he chose Eddie Lou.

JM: Did she continue to go to school?

SP: Yes, but I don’t know how far she went.

JM: Did she tell you about growing up with the Parkers?

SP: She told me that the farm community would get together on Friday and Saturday nights. They would gather around the organ, which her mother played, and everybody would sing. They also made candy and played games. On Sunday, they went to the Salem Methodist Church, in the New Era community in Sumter County (eight miles northeast of Americus).

JM: When did she get married?

SP: She married Hawkins Parker on August 28, 1920, at the Salem Methodist Parsonage.

JM: Did she work after she got married?

SP: She never worked. Hawkins always provided for her, even with a maid. He was a carpenter, and then he went to work for the railroad. Sometimes he would have to go to Florida, and he would be gone for several months. That’s after they bought the house in Plains. They also inherited the farm in Americus from her mother, which Eddie Lou deeded to her son, Maurice Parker, who was my husband. He sold the farm in 2001.

JM: How many children did they have?

SP: Seven. Her son, James Clinton Parker, was killed in the war. And she lost a child later on in life.

JM: When did you meet her?

SP: In 1954, when I married Maurice. I met him in Plains. My father was a farmer down in South Georgia, but he finally left the farm and got a job on a cattle farm in Plains.

JM: Earl told me that Eddie Lou and her family knew Jimmy Carter.

SP: They were neighbors. He and his wife Rosalynn lived just a few doors down from Maurice and me when we got married. They were living in the public housing apartments. They walked up and down in front of our house when they went to church. He doesn’t know me personally, but when my husband passed away three years ago, they sent a memorial.

JM: How well off financially were Eddie Lou and Hawkins?

SP: Because they had a lot of children, they always had some difficulties. They lived from paycheck to paycheck. But Mr. Parker was a wonderful man and always provided for the family the best he could. They didn’t wear fancy clothes, but they always had enough to eat. Eddie Lou was a wonderful cook. She could take a can of salmon and feed nine people. They had a nice home, with plenty of room for the children.

JM: Did she live in that home the rest of her life?

SP: No. She fell and broke her hip in about 1971, and that’s when they moved down with us in Albany so I could take care of them while my husband was working. He was the manager of the local A&P grocery store. We had an extra home there that was given to us, so we let Eddie Lou and Hawkins live there. I took care of her home and did the grocery buying. Hawkins was already beginning to get Alzheimer’s. My husband retired from A&P at the age of 43 and bought his own grocery business. We had a three-bedroom apartment on the back side of the building, so we put Eddie Lou and Hawkins in there so we could watch them all the time. My husband and I took care of them daily.

JM: How did Eddie Lou spend her time when she was ill and couldn’t do the things she had always done?

SP: It didn’t change her lifestyle that much. She read constantly. She was a great lover of the Bible. She would read it daily. She loved to read westerns, and she loved Earl Stanley Gardner (writer of Perry Mason stories). She named her son Earl after him. She became friendly with some of her neighbors. They joined the local church and became very active in it. That was the Baptist church. Hawkins was a Methodist, and she was a Baptist. She watched TV and was always up to date on local and national news. And, of course, she talked about Jimmy Carter a lot.

JM: Did you know Eddie Lou’s sister Mell?

SP: I met her. She would visit Eddie Lou occasionally, but they weren’t close.

JM: What about Mattie?

SP: I never met her. But in the picture I gave you, that was the first time Eddie Lou had seen Mattie since they had been adopted. Mattie probably had come to Albany to visit Mell, and Eddie Lou went down to visit them.

JM: Did you ever meet Mary?

SP: I don’t know anything about her.

JM: Did you know her brother Alex?

SP: Yes. We called him Roy. He had a drinking problem, and he liked the girls, although I don’t think he ever married. He came down and visited Eddie Lou a few times. Like her, he was a great talker. He would tell tall tales about being in the service and being over in Japan. He loved the Japanese women. He also loved to travel.

JM: Seaborn?

SP: I think I met him at Roy’s funeral. He lived in Baxley.

JM: Did you know Elzy, Elizabeth or Jesse?

SP: No.

JM: Did Eddie Lou have a relationship with her real mother, Catherine?

SP: Catherine lived in Albany. She saw her a few times. She called her ‘Mother,’ and she called Mrs. Parker ‘Mama.’ Catherine visited her in Plains once.

JM: Did Eddie Lou resent that Catherine put the children in the orphanage?

SP: I never got that impression.

JM: Did she mention Jesse, her real father?

SP: No.

JM: She was very beautiful in that Lewis Hine photo of her with the other girl, and she was just as beautiful in the photo when she was 18.

SP: She was a beautiful woman all of her life. She took good care of herself. And she was a very loving person. Since I grew up without a mother, she was like a mother to me. I started calling her “Grandma’ after we adopted a son. When she got cancer, we kept her at her home. I sat with her the last 72 hours of her life. The afternoon she died, I had gone into the apartment to check on her, knowing she was probably in her last hours. I gave her a bath and dressed her in a beautiful green gown that she had. I said, ‘Grandma, I’m going to help Maurice close up the store, and I’ll be right back. Will you be okay?’ And she said, ‘Sure, darling.’ As I walked out the door, she said, ‘I love you darling.’ Those are the last words she ever spoke.

After this story was published, I received an email from Beth Williams, one of Eddie Lou’s granddaughters. I have posted it with her permission.

“My Uncle Earl, Eddie’s Lou’s son, was one of the persons you interviewed in your article about the Young family. She was my grandmother. I grew up living in the country just outside of Plains and have many memories of her. I stayed with her quite often while my parents worked, so we talked quite a bit.”

“My grandmother dipped snuff as you mentioned in your story. She kept an empty Crisco can stuffed full of toilet tissue by her chair to spit in, and we were always cautioned not to tip it over when we walked close to her chair. She was always smiling, and when I entered her home I always ran straight to her chair and gave her a kiss before doing anything else. She kept Vaseline on her lips, so she would wipe it off and give me a kiss on the lips, and she would say, ‘There’s my darling.’ When I think of her today, I can still see her sitting crossways in her stuffed chair with her leg over the arm and her Bible in her lap. She was always reading the Bible. Our favorite thing to play was church. We would read from the Bible, then we would sing songs together from the hymnal she had.”

“I find it ironic that Uncle Earl was told by his teacher, Ms. Coleman, to look into a vocational rehabilitation scholarship, which would pay his tuition so he could go to college. I just finished my master’s degree in vocational rehabilitation this past December and am currently working as a counselor in the Georgia Vocational Rehabilitation Agency. Many of our clients still ask about the vocational rehabilitation scholarship. Another ironic twist is that I also worked in a cotton mill, from 1974-1982, and was in the spinning department, just as my grandmother was. I did not know that she had worked in a cotton mill until I read your story, as she never mentioned it to me.”

“She told me one time when I was a teenager that she was in an orphan’s home as a young girl. She told me that people in town talked her mother into putting her and her brothers and sisters up for adoption because she couldn’t take care of them. She told me that she didn’t see her mother again until after she was married and had children of her own.”

“Thank you so much for your research. It brought such enjoyment to me and flooded back many memories of good times.”