Lewis Hine caption: Ebb-tide in the industry. Family of Mrs. Wm. Fuqua. On account of slack work in the cotton mill, her husband recently got work up-town. He is the only wage earner. Six in the family. The oldest girl is 14 years old now. She worked last year, but the lint affected her so much they had to take her out. Location: South Boston, Virginia, June 1911.

“She was an excellent seamstress. She could make clothes by cutting a pattern out of newspaper and then putting it down on cloth and sewing it by hand. When you’re poor, you learn to do those things.” -Beverly Ault, granddaughter of Florine Fuqua

Lewis Hine took six photographs in South Boston, Virginia, all of children and families who worked at the Century Cotton Mill, later the Halifax Damask Mills, sometimes called simply the Halifax Cotton Mill. That is where Florine’s father would have been working until there was “slack work.” His new “up-town” job was probably at one of the tobacco processing factories or warehouses. Florine would have also worked at Century until, as Hine said, “the lint affected her so much they had to take her out.” According to an illustrated walking tour posted on OldHalifax.com, the Halifax Damask Mill “held the patent for the red-checked damask which is used for tablecloths in so many restaurants worldwide.”

The following is from a 1986 application by the town to obtain nomination of the area around the Halifax Cotton Mill to the National Register of Historic Places.

“While South Boston’s late 19th-century economy depended upon the tobacco industry, the textile industry also figured prominently in the early development of the town. In 1897 the Century Cotton Mill, later known as Halifax Cotton Mill, was established along Railroad Avenue, southwest of town. The original two-story brick factory still survives. A larger rectangular structure punctuated by rows of tall segmental-arched windows on both floors, its most characteristic feature is a tall square brick entrance tower centrally positioned along the building’s principal façade. The tower has tall paired round-arched windows and a horizontal row of circular openings on each elevation. Brick corbelling and heavy crenellation gives the tower a medieval appearance. Sympathetic rear and side additions date from around 1927.”

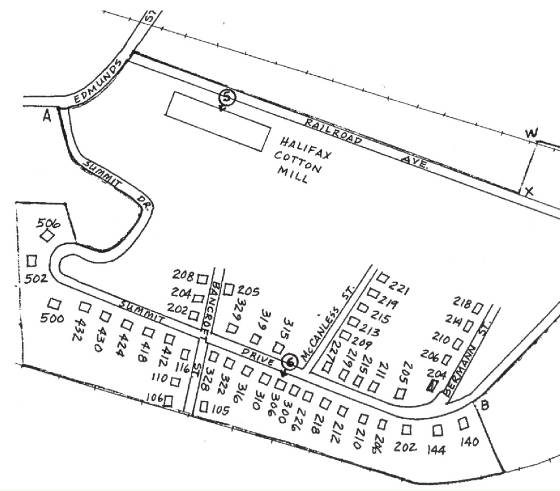

“Situated on a hill high above the Halifax Cotton Mill is a collection of forty-eight dwellings that were originally built around 1900 as employee housing by the cotton mill. Comprising a company town set apart from the city below, this area consists of modest single-story frame houses of three types. Most of the houses are weatherboarded structures with shallow gable roofs and paired or single central brick chimneys and a simple three-bay porch. Other houses, perhaps residences of higher ranking employees, are larger hip-roofed structures with asymmetrically positioned recessed front porches. At least two houses are 1 ½-story New England saltbox-type dwellings with central brick chimneys and full-length five-bay front porches. Situated on general lots, these houses were probably inhabited by foremen or managers of the cotton mill and their families. Although now individually owned by residents, the houses have retained a basic uniformity with few modern alterations.”

The millhouses were just south of the mill, along Summit Drive and the tiny streets off Summit. The house in Hine’s photograph was probably one of them. The mill was demolished about 10 years ago, except for the tower and a smokestack.

Florine Fuqua was born January 29, 1898, in Person County, North Carolina. She was one of 12 children born to Captain William Fuqua and Rebecca “Mollie” (Edwards) Fuqua. They married in 1893. Three of the children died either at birth or in early childhood. Apparently, her father’s first name was actually Captain. Florine married William Weaver about 1917. A veteran of the Spanish-American War, he was 15 years older than she. In the 1920 census, they were living on Edmunds St. in South Boston, no more than a few hundred feet from the Halifax mill. William is working as an insurance solicitor. Their first child, Ethel, is one year old.

By 1930, they had six children, including twins John and James. They would have four more. They lived on a farm in the Birch Creek section of Halifax County, near South Boston. Her husband died in 1960. Florine died in 1981, at the age of 83, leaving six children, 21 grandchildren, and 20 great-grandchildren.

I located and interviewed a granddaughter, Beverly Ault, through a family tree posting on Ancestry.com; and corresponded with Florine’s grandson, James Weaver. There are no photographs available of Florine other than the one taken by Lewis Hine.

Edited interview with Beverly Ault (BA), granddaughter of Florine Fuqua, and daughter of Florine’s son James. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on January 4, 2011.

JM: What was your reaction to the photograph?

BA: The first thing I wanted to know was whether it was really her, my father’s mother. But then I looked at her face and I knew it was her. She had a distinctive nose. It was kind of turned up. And then I had to scrutinize the whole picture, and I realized that the woman would have been her mother, and the children would have been her siblings. I recall my mom saying that my grandmother was one of 10 children, and that she had younger brothers and sisters, so it made sense that it was her. Finally, I began to appreciate how poor they looked.

JM: The caption states that she was taken out of the mill because she was bothered by the lint. It probably caused breathing problems. Do you remember her having any problems like that?

BA: No.

JM: Did you know that she worked in a cotton mill?

BA: No, I didn’t, not as a child. And when she got married and had 10 kids, I doubt she would have had time to work. She did talk a little in generalities about having to work as a child, but that’s all I know. My father said that they were so poor, that he and his brothers and sisters had to work on tobacco farms in the summer. I found that fascinating.

JM: When were you born?

BA: 1957, in Pittsburgh.

JM: Your grandmother died in 1981, so you knew her quite a while.

BA: Yes, but I didn’t see her much. My dad moved to Pittsburgh in 1946 to work in a factory. My grandfather on my mother’s side was a foreman in one of the mills here, so that’s why he came up. My parents were married the same year. So I didn’t grow up near my grandmother. The few times we would visit her in Danville (Virginia), we spent more time with my mother’s side of the family.

JM: When you did get a chance to visit her, did you enjoy that?

BA: Yes, but we were reared in that ‘children are seen and not heard’ era, so when adults were talking, we weren’t allowed to interrupt or include ourselves in the conversations. We were usually sent outside to play. I remember that my sister always had a big, white smile, and my grandmother would say to her, ‘Gosh, girl, are those your teeth?’ My sister was shy, so she’d just blush and turn away. I don’t remember much about those visits. I didn’t talk to her that much. I don’t even remember staying for dinner. I recall that there was lattice work under the porch, and she used to tell me that there was an alligator under there. Then I found out that she didn’t want me to go under the porch because there were stray cats and dogs there sometimes, and she was afraid that I might get bitten.

My grandmother was kind of tough. There were seven boys and three girls, and she had to keep them in line. My father told me that he was more afraid of her than his father; well, not really afraid, but you know what I mean. I remember my dad saying that she could ‘make gravy out of water and biscuits out of flour.’ He said that she was strict and demanding, but he always knew his parents loved him.

JM: Did your dad graduate from high school?

BA: No, and I’m pretty sure my grandmother didn’t either.

JM: Did either your father or your grandmother seem like they were educated, despite not finishing school, or did they appear uneducated?

BA: I would say that they appeared uneducated. They had lots of common sense, but they weren’t book smart. Even though my parents were from the South, they fit in well with people up here. Pittsburgh is very diverse, but they didn’t have any prejudices. My dad told me once: ‘When I was growing up on the farm, we worked next to black people. There was nothing not to like about them. We had to look out for each other, because when you’re working on a farm, it’s kind of dangerous. When the sun is hot and you’re working your butt off, you’re not going to waste your time hating someone.’

JM: What did your father do for a living?

BA: He worked for US Steel in Braddock (Pennsylvania). But in the 1970s, when times were tough here, he used to get laid off a lot, and he would take part-time jobs such as working for a butcher. I asked him how he knew how to do all that, and he said that his parents taught him how to do all kinds of stuff. His mother could do many things well. She was an excellent seamstress. She could make clothes by cutting a pattern out of newspaper and then putting it down on cloth and sewing it by hand. When you’re poor, you learn to do those things. And she loved to play the harmonica. The whole family was musically inclined.

JM: Your grandfather died in 1960, so she was a widow for a long time. How did she support herself?

BA: I think one of her sons lived with her for a while. Because she was tough and self-sufficient, I never got the sense that anybody worried about her.

JM: What do you think about the fact that the photograph was used to influence public opinion about child labor?

BA: I was surprised. To think there was a man out there in 1911 concerned enough about child labor to take these pictures; that astounded me. I hope somebody paid him to do that.

**************************

“My grandmother, Florine Fuqua Weaver, was a very pleasant, fun person. She always handed out compliments and could tell jokes one after the other. She was a tall person, medium build, always had on a dress, and to me, she looked exactly like a grandmother should look. She also dipped snuff. She always mentioned my grandfather by calling him Mr. Weaver, never by his first name. She loved to talk about her children and about Mr. Weaver being in the Spanish-American War. He was a lot older than she. She is one of the few people who called me James instead of Jimmy. I’ve been told she could play the banjo and the harmonica or Jew’s harp. The thing I miss about her most is her smile. She never mentioned her days as a child, only that she lived in South Boston. And she never mentioned that she worked after she got married. I loved the old picture of her that you found. I never saw a picture of her as a girl before. She was a good Christian woman, and she was a wonderful blessing.” -James Lee Weaver, grandson of Florine Fuqua.

*Story published in 2011.