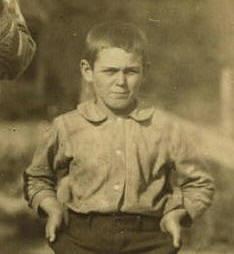

Lewis Hine caption: Extremes of age in the Belton Mfg. Co., S.C. The boy is Fred Willingham. Been working six months in the Bolton Mfg. Mill. Gets 50 cents. Sweeps. His next older brother has been doffing a year or two. Fred and his older sister had some confusion about the age, first making him out “goin on 12” and then they raised it. Sister said record was not in the bible. Father and two boys in the mill. Location: Belton, South Carolina, May 1912.

“He loved baseball. His favorite teams were the New York Yankees and the Cincinnati Reds. He especially liked Ruth and Gehrig. We would always listen to a baseball game at night during the season.” -Jerald Willingham, son of Fred Willingham

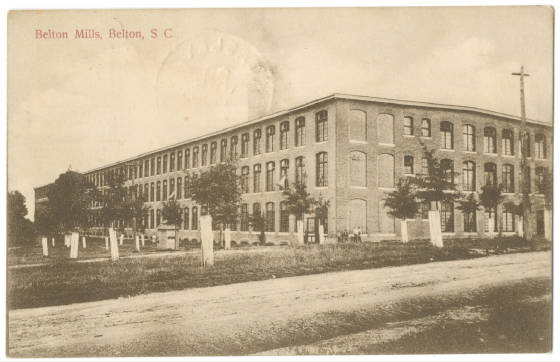

The following was published in the Report of State Officers, Board and Committees to the General Assembly of South Carolina, 1901:

The Belton Mills employs 500 operatives, and are not yet in full operation, having only started in July. This mill is in the town of Belton, and we expect the children living in the mill village to attend the Graded Schools in the town of Belton, and we do not propose to have any mill school at Belton, or to separate the children of the mill people from the children of the town people. As this mill is hardly yet under full swing, I am unable to give you the information as to the amount paid by the Belton Mills for the support of schools, etc.

It may interest you to look at the contract signed by people moving into Pelzer and Belton mill villages, and you will see how anxiously we work to encourage the children of our employees to attend school, both at Pelzer and Belton. If we had compulsory attendance school laws it would help us very much in mill villages, but any laws attempting to regulate child labor are dangerous. -Ellison A. Smyth, President of Belton Mills

Ellison Adger Smyth, president of Belton Mills when Lewis Hine visited the mill village, was born in Charleston, S.C., on October 26, 1847. In 1880, he established the Pelzer Manufacturing Company, creating a modern mill village in Pelzer, South Carolina. The first mill was built in 1881, and had 10,000 spindles. More mills were added in the village over the next few years, resulting in a total of 136,000 spindles. Smyth was the first president and treasurer, and continued in those positions for 43 years. He built the first cotton mill with incandescent lights, and he was one of the first to install electricity in cotton mills in the South. In 1899, he organized a partnership to build cotton mills in Belton.

Smyth was generally an opponent of child labor laws, believing that compulsory school attendance and reliable age verification would be a more useful tool in giving children better opportunities, and providing the textile industry with better skilled employees. Consequently, he vociferously challenged the efforts of the National Child Labor Committee, and he often made questionable claims about the extent to which children under the age of 12 were working in cotton mills in the South, and the number of child workers that were illiterate. He died in 1942, at the age of 94. -Compiled from newspaper articles, information posted on TextileHistory.org, and records from the National Child Labor Committee

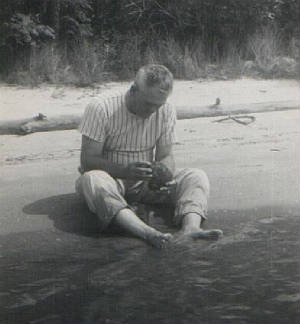

Lewis Hine took 14 photos at Belton Mills, none as striking or unusual as the one of Fred Willingham. The picture is dominated by the figure of the unidentified bearded man. I guessed that he might be Fred’s grandfather, but family members I talked to stated emphatically that he was not, and that he was probably not related to Fred at all.

Hine pointed out in several of his Belton photos that children were apparently working under the minimum age limit of 12. My research indicates that Fred was two months short of his 12th birthday. If his claim that he had already been working at the mill for six months is correct, he would have wound up working illegally for a total of eight months before the age of 12.

CHILD LABOR LEGISLATION IN THE CAROLINAS

By John Porter Hollis, Special Agent, National Child Labor Committee, 1911.

Prior to the legislative session of January-February, 1911, there were child labor laws in South Carolina providing for a sixty-hour week, factory inspection and a twelve-year age limit. But the twelve-year limit did not apply to orphans, or to the children of widowed mothers or totally disabled fathers. The law also permitted anybody’s children under twelve to work during the summer months, provided they had attended school during the winter.

The South Carolina Child Labor Committee, at a meeting in November, 1910, decided to ask the legislature to pass a bill repealing the poverty exemptions, prohibiting work at night of children under sixteen, and gradually raising the age limit for day work to fourteen years. This legislative program was published and at once aroused the opposition of the manufacturers. At the next meeting of the committee in December, representative manufacturers were present and announced that they would not oppose elimination of all children under twelve, and abolition of night work for children under sixteen, but that they would fight any effort to advance the age limit above twelve years, unless compulsory education were coupled with the advance. They contended that if children up to fourteen years were neither in the mills nor in the schools, they would develop into a dangerous class of loafers and budding criminals. The committee either took fright at the attitude of the manufacturers or decided that it would be better to make as sure as possible of at least some improvement, and reconsidered its former action to the extent of striking out the most important feature of the proposed bill – that is, the raising of the age limit.

The mutilated bill was introduced early in the session in both Senate and House and passed the Senate without difficulty. But it barely escaped defeat in the House, and doubtless would have failed to pass but for an earnest personal canvass of practically every legislator. The opposition in the House was composed of several elements: (1) certain owners of cotton mill stock, (2) politicians representing certain counties containing large numbers of factory voters, (3) legislators seeking political favors at the hands of other legislators, (4) sincere men who feared that the inflexible operation of the law would cause suffering to many worthy but unfortunate families. But despite the stubborn fighting of its opponents, the bill became a law, and it was encouraging to see that the friends of the bill were as strong in its favor as were its enemies in opposition.

The fight in the House made it clear that the chief difficulty in the way of all child labor legislation in South Carolina is the supposedly unfriendly attitude of the mill operatives. “Let us alone,” is the constantly quoted answer to all appeals for improvement. Apparently there is a very large element of men in the factory villages who work very little, but who talk a great deal and vote in every primary. This seems to be the man, rather than the mill president, of whom the legislator is chiefly afraid. And presumably he desires to be let alone in order that he may live in idleness while his helpless children toil.

South Carolina’s law now prohibits night work for children under sixteen, provides factory inspection, a sixty-hour week, and an absolute twelve-year age limit for day work. Naturally, the next step is to raise the age limit to fourteen years. And this will be no easy thing to do, as the combined opposition of both manufacturers and operatives may be expected. It is probably useless to hope for a change of heart on the part of the manufacturers, and I am convinced that about the only way to win over the operatives is by demonstrating to them that the competition of cheap child labor has the tendency to drag their own wages down. It is not fair to say that there are no parents among the operatives who are ambitious for their children and who oppose their exploitation; but even these are timid and fear to assert their wishes lest they may call down upon themselves the wrath of the mill owners. A cotton mill organization in South Carolina is a feudal system, wherein the operative is a vassal, one of whose feudal obligations is to do homage to his lord, the mill president, for the privilege of grinding in his lord’s mill and living in his lord’s tenant house.

************************

It was easy to track down Fred’s descendants. I found some of his family history, and some photographs of him posted online by Diane Culpepper, one of his granddaughters. I got in touch with her. She had no useful personal recollections of Fred, but she referred me to her Uncle Jerald, one of Fred’s sons, who had a wealth of information. Both Diane and Jerald discovered the Hine photo several years ago.

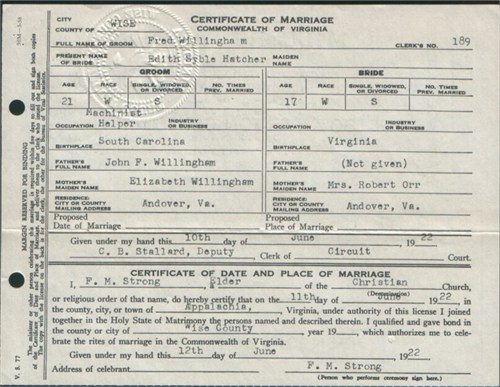

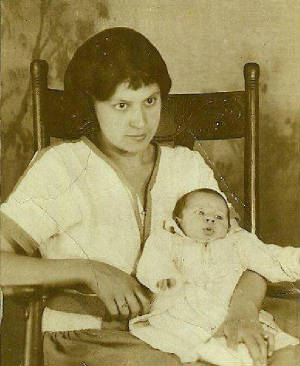

Fred Willingham was born in Belton on July 1, 1900, one of at least nine children born to John Franklin Willingham and Nancy Elizabeth King. Practically the whole family worked at Belton Mills in the early 1900s, including father John, who was a bookkeeper at the mill. Fred served in the Navy in World War One, and then moved to Andover, Virginia about 1921, to work for the Interstate Railroad. He married Edith Syble Hatcher there in 1922. They had six children.

Fred worked for the railroad until his retirement, and passed away on March 2, 1967, at the age of 66. He died in Georgia, while visiting relatives, but he and Edith were still residents of Andover.

Edited interview with Jerald Willingham, son of Fred Willingham. Interview conducted by Joe Manning on August 28, 2013.

Manning: When did you first see the Lewis Hine photo of your father?

Willingham: About two years ago. Several of my relatives found it and sent it to me.

Manning: What did you think of it?

Willingham: I was shocked. I could tell right away that it was my dad. But I have no idea who the man standing next to him was.

Manning: When were you born?

Willingham: In 1933.

Manning: Where were your parents living at that time?

Willingham: They were living in Andover, Virginia. My father was working for the Interstate Railroad.

Manning: When had he left South Carolina?

Willingham: I’m not sure. He joined the Navy when he was 16. He lied about his age to get in. He served in World War I, and was on a mine sweeper in the North Sea, sweeping and laying mines. He never said much about it. He got out of the Navy in 1921, and ended up in Andover. His oldest brother worked on the Interstate Railroad there, and I guess he got my father a job. He probably started out as a shop boy, and then he became a machinist. He worked on the old steam locomotives. Then he got promoted to the master mechanic job. He stayed there until he retired, at age 65. When I was young, I used to go to work with him at the railroad. I’d just hang out with him and get dirty. I wasn’t too cool about crawling under those steam engines. It was sort of scary. My father was a great machinist. He built a car that the rail inspectors used. He made it out of a junked Hudson, put a Studebaker engine in it, and converted it so it could run on the rails.

Manning: How did he acquire those skills?

Willingham: He was a machinist in the Navy.

Manning: What did your father tell you about growing up in Belton?

Willingham: Not much. He just said that they didn’t starve, but they weren’t rich. It was a big family, and most of what he had was hand-me-downs.

Manning: Could he read and write?

Willingham: My oldest brother’s wife told me that my father could not read and write when he got married, but Mom taught him how to do it. I always remember him having beautiful handwriting. And he would read the newspaper every day.

Manning: Did he work all the time, or did he have time for you and the family?

Willingham: He would work, come home, wash up, have supper, and then usually listen to the radio. He loved baseball. His favorite teams were the New York Yankees and the Cincinnati Reds. He especially liked Ruth and Gehrig. We would always listen to a baseball game at night during the season. We could get stations like WCKY in Cincinnati, which broadcast the Reds games, and KDKA in Pittsburgh which did the Pirates games. We also listened sometimes to a station in Cleveland that carried the Indians games. And we also listened to football games. He had a big console radio that had shortwave on it, so we could listen to the Armed Forces Network, and get the Army games and the Navy games. His friends on the railroad would come in and sit around and listen to baseball games. And I would sit there and listen, too. One time, I went with him and his buddies to Knoxville to see a University of Tennessee football game. It was the first time I had ever eaten out in a restaurant.

Manning: Were you a big baseball fan?

Willingham: Yes, and I still am. I root for the Washington Nationals and the Atlanta Braves.

Manning: Did you graduate from high school?

Willingham: I quit in the 12th grade and joined the Navy. But I ended up getting my GED. I was in the Navy for four years, and was trained as an aircraft mechanic. Then I went to work as an aircraft mechanic for Eastern Airlines, first in Miami, Florida, and later in Atlanta. I did that till I retired in 1991, when Eastern went out of business. So I was with them about 37 years.

Manning: Did any of your siblings graduate from college?

Willingham: One sister did.

Manning: When you were growing up in Andover, during the Depression and World War II, were your parents financially comfortable, or did they struggle?

Willingham: I guess my parents lived from paycheck to paycheck. They made it through okay. We had a cow and some chickens. I don’t remember ever going on vacation.

Manning: Did your mother work out of the home?

Willingham: During the war, she worked for the Post Office, which was just across the road from our house. She ended up being the postmaster, and she worked there until she retired.

Manning: Did your parents own the house?

Willingham: They rented it from the railroad company for many years, and then the company sold the houses to the workers that lived in them. Each house had a number on it, and ours was 95, but the street had no name. My parents were still living there when my father died, but he actually died in my house in Georgia. Mom died in 1982, 15 years after he died. She was living then in a little apartment near my sister, who lived in Perry, Georgia.

Manning: What was your mother like?

Willingham: She was a typical mom. She had six kids. Wash day was on Monday. Then she would sprinkle them down on Tuesday, and iron them on Wednesday, and do all the other chores.

Willingham: My father had a real good sense of humor, and he liked to tell jokes. He would sit on the front porch and talk to everybody that went by. People say I’m a lot like Daddy because I’ll talk to anybody. He started a tradition. He was in the Navy. Then I was in the Navy, my three brothers were in the Navy, and both of my sisters married Navy men. I had a son who was in the Navy, and my oldest brother had a son that was in the Navy.

Daddy told me that when he was a boy, he used to come home from the cotton mill covered with dust and lint, and he wondered how much of that stuff he had inhaled into his lungs. But he was a smoker. He died with a cigarette in his hand. He was sitting on a couch in my house and suddenly fell over. He had a heart attack. He was a great guy.

Fred, top row at right; Edith, second row in middle; plus their children: Jerald, top row left; Elva, top row middle; Harold, standing in front of Jerald; Shirley, standing in front of Fred; Bobbie, second row, third from left; and Edward, second row middle, standing to Bobbie’s left; plus assorted spouses and grandchildren. Picture taken about 1949 on front steps of Willingham house in Andover.

Jerald Willingham, Fred’s son, wrote an essay called “Things I Remember Growing Up.” It is a heartfelt, colorful, and often humorous account of his life as a boy growing up with his parents and siblings in a rural railroad town in Virginia. I highly recommend it because it adds more insight into the life of Fred Willingham and his family. Click below for a nine page PDF.

Stories of growing up, by Jerald Willingham

*Story published in 2013.