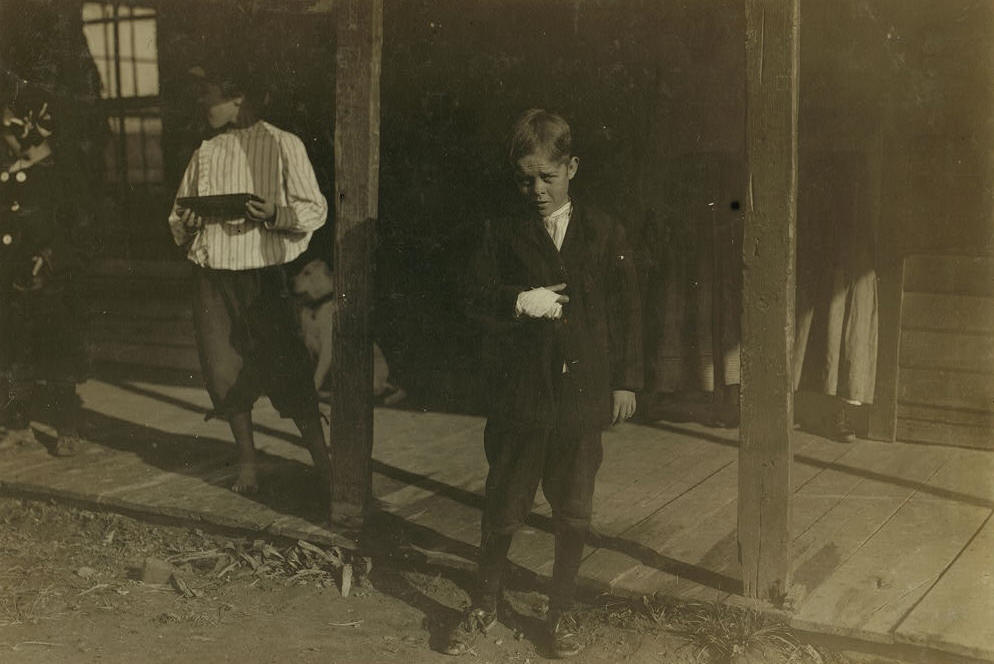

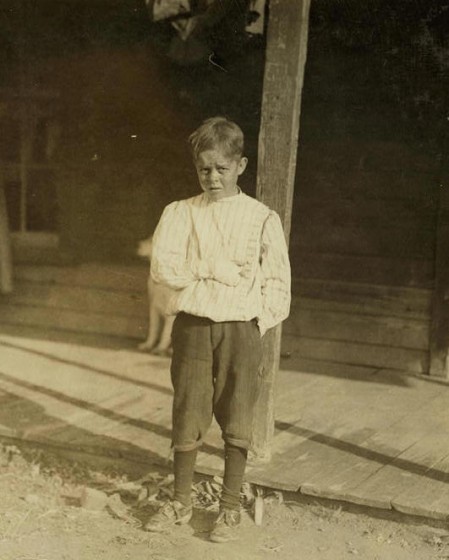

Lewis Hine caption: Accident to young mill worker. Giles Edmund Newsom (Photo October 23rd, 1912) while working in Sanders Spinning Mille [i.e., Mill], Bessemer City, N.C., August 21st, 1912, a piece of the machine fell on to his foot mashing his toe. This caused him to fall on to a spinning machine and his hand went into unprotected gearing, crushing and tearing out two fingers. He told the Attorney he was 11 years old when it happened. His parents are now trying to make him 13 years old. The school census taken at the time of the accident makes him 12 years old (parents’ statement) and school records say the same. His school teacher thinks he is 12. His brother (see photo 3071) is not yet 11 years old. Both of the boys worked in the mill several months before the accident. His father, (R.L. Newsom) tried to compromise with the Company when he found the boy would receive the money and not the parents. The mother tried to blame the boys for getting jobs on their own hook, but she let them work several months. The aunt said “Now he’s jes got to where he could be of some help to his ma an’ then this happens and he can’t never work no more like he oughter.” Location: Bessemer City, North Carolina.

“The year 1904 saw the first child labor laws go into effect in North Carolina. The law limited the work week for all workers to a maximum of sixty-six hours and stated that no child under the age of twelve could be employed by a mill. However, the law came bundled with a list of mill-friendly exceptions which rendered the law a mere half-hearted intention. Stipulations were attached to the bill exempting engineers, firemen, machinists, superintendents, overseers, section and yard hands, office men, watchmen, and repairers of breakdowns. The law, which carried no provision for enforcement, empowered employers with a multitude of ways to ignore it.”

“In 1907 the child labor law was revised. The old stipulations were stripped and the law was reworded to state that no child under the age of fourteen shall be employed by or work in a mill. However, the law carried a new stipulation: boys and girls between the ages of twelve and thirteen could work in a mill under an apprenticeship providing the child had attended school for at least four months out of the preceding twelve. For the mill’s management a simple written note from the child’s parents was all that was required for proof of age or schooling. The penalty for parents who lied about their child’s age, or for mills found operating outside the realms of the law, was set as a misdemeanor. The law also declared that no boy or girl under age fourteen was permitted to work in a mill between the hours of eight P.M. and five A.M.” -from Report on Condition of Women and Child Wage-Earners in the United States: The Beginnings of Child Labor Legislation in Certain States; A comparative Study, Volume VII (1910); and Uniform Child Labor Laws: Proceedings of the Seventh Annual Conference of the National Child Labor Committee (1911)

Lewis Hine spent nearly the entire month of October photographing mill workers in North Carolina, but in November, he was in New England, New York and New Jersey. His constant traveling didn’t afford him the opportunity to revisit his subjects and record updates on how they were doing. And so 100 years later, we are left wondering what happened to Giles, the boy with the missing fingers. Other than one surprising piece of information, my research turned up very little.

When Giles was injured, he was eight days short of his 12th birthday. According to North Carolina laws, the minimum age to work in the mill was 12, but only if the child was just an apprentice and was attending school at least four months in a calendar year. Otherwise the minimum age was 14. Bessemer City is a small city just north of Gastonia. The Sanders Spinning Mill where he worked (officially called Sanders Spinning Co.) began its operations in about 1910, in a mill formerly owned by Mascot Cotton Mills. In 1914, Sanders was purchased by M. Gambrill & Associates.

Lewis Hine caption: Where it happened. Sanders Cotton Mfg. Co., Bessemer City, N.C. In this and the adjoining mill (run by the same company) there were still many dangerous, unprotected gears, belts, belts running through the open floor, rough broken flooring on which the workers would likely stumble, etc.- when I went through these mills (October 23rd, 1912) over two months after the accident. Location: Bessemer City, North Carolina.

Lewis Hine caption: Accident to young mill worker. Giles Edmund Newsom (Photo October 23rd, 1912) while working in Sanders Spinning Mille [i.e., Mill], Bessemer City, N.C., August 21st, 1912, a piece of the machine fell on to his foot mashing his toe. This caused him to fall on to a spinning machine and his hand went into unprotected gearing, crushing and tearing out two fingers. He told the Attorney he was 11 years old when it happened. His parents are now trying to make him 13 years old. The school census taken at the time of the accident makes him 12 years old (parents’ statement) and school records say the same. His school teacher thinks he is 12. His brother is not yet 11 years old. Both of the boys worked in the mill several months before the accident. His father, (R.L. Newsom) tried to compromise with the Company when he found the boy would receive the money and not the parents. The mother tried to blame the boys for getting jobs on their own hook, but she let them work several months. The aunt said “Now he’s jes got to where he could be of some help to his ma an’ then this happens and he can’t never work no more like he oughter.” Location: Bessemer City, North Carolina.

Giles Edmund (or Edmond) Newsom was born in South Carolina on August 29, 1900. His parents were North Carolina natives Robert Lee Newsom and Minnie (McAbee) Newsom. They married in about 1900. According to the census, the family was living in Catawba, South Carolina in 1910. Robert worked in the card room of a cotton mill. They had three children, Giles, Barney, and Marjorie. By 1912, they were living in Bessemer City.

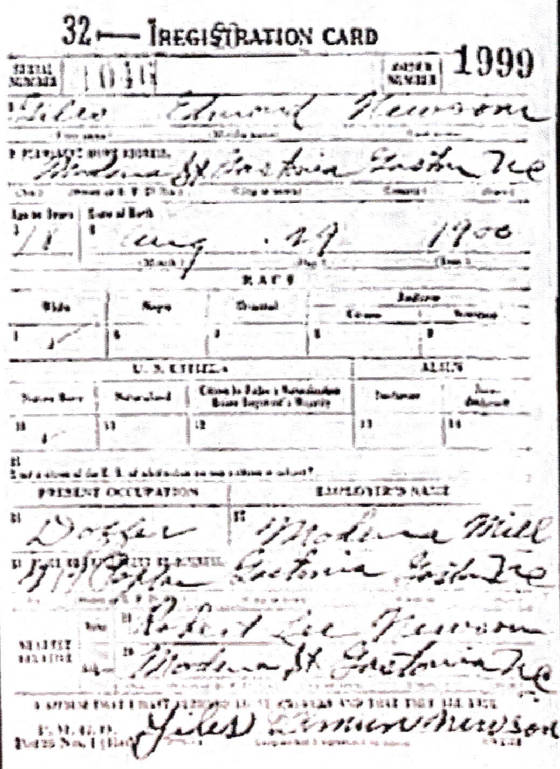

In September of 1918, Giles registered for the draft. On the draft registration form, he gave his address as Modena Street in Gastonia, and his nearest relative as his father, who lived at the same address. On the form, the question was asked, “Has person lost arm, leg, hand, eye, or is he obviously physically disqualified?” Giles answered, “Two middle fingers off of right hand.” But surprisingly, he listed his occupation as a doffer in Modena Mills, where his father also worked. Despite losing two fingers, he was back doing the same work. According to available city directories, Robert Newsom remained in Gastonia until at least the middle 1930s, although neither he nor any other family members appeared in the census in either 1920 or 1930. Giles was not listed in the census or the directories.

Minnie, Giles’s mother, died in 1927, but her brief obituary did not list survivors. Robert remarried, to a woman named Bessie. He died in Salisbury, North Carolina, in 1949. His obituary did not list Giles as a survivor, but listed his other two children, Barney and Marjorie. Barney died in 1965, and Marjorie died in 1981, but their obituaries also did not mention Giles. I could not locate any of Barney’s children, and Marjorie’s only child died in 2000, and he had no children.

After his 1918 draft registration, Giles does not appear in any available records, including North Carolina death records, which are posted online from 1908 to 2004. What happened to him?

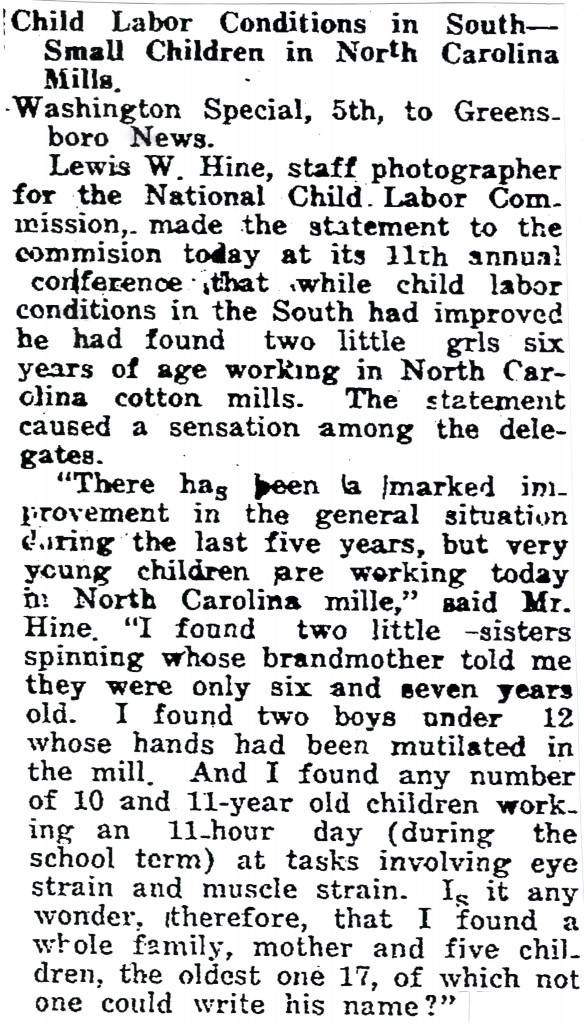

Article below was published 27 months after Lewis Hine photographed Giles.

Article below was published 20 years after Lewis Hine photographed Giles.

The following is from “Children Hurt At Work,” by Gertrude Folks Zimand, National Child Labor Committee, published in The Survey in 1932:

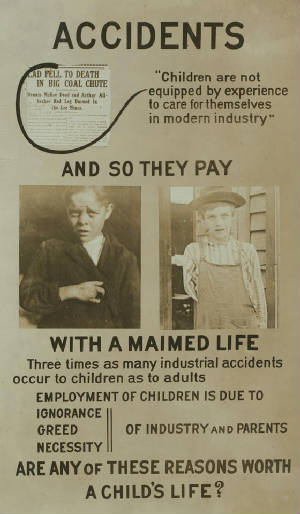

“One of the many tragic aspects of the industrial exploitation of children is the army of boys and girls who, at the outset of their industrial careers, fall victims to the machine. Each year, in the sixteen states which take the trouble to find out what is happening to their young workers, no less than a thousand children under eighteen years are permanently disabled and another hundred are killed.”

“It was Florence Kelley, the pioneer in this field, who first maintained that the term “industrial accidents” as applied to children was a misnomer and insisted that we speak of industrial injuries. For an accident, she pointed out, implies something which just happens, which cannot be prevented, whereas such wholesale maiming of children by industry constitutes criminal negligence. But unfortunately permitting half-grown youngsters to assume the risk of accident is but the first step in a general laissez-faire policy.”

“Charles E. Gibbons, assisted by Chester T. Stansbury, has been making for the National Child Labor Committee a follow-up study of children who were seriously injured in industry four or five years ago. So far 108 children have been studied in two states, Illinois and Tennessee. These children, now nearly adult, had been maimed physically, often to the extent of a lifelong handicap, and had undergone the experience of seeing their whole future jeopardized just as they were emerging from childhood to adulthood-a period at best of emotional stress and strain. Yet in this crisis, the protecting arm of the state had not been extended, and the children had been left to make their adjustments as best they might.”

Mill Doors

You never come back.

I say good-by when I see you going in the doors,

The hopeless open doors that call and wait

And take you then for – how many cents a day?

How many cents for the sleepy eyes and fingers?

I say good-by because I know they tap your wrists,

In the dark, in the silence, day by day,

And all the blood of you drop by drop,

And you are old before you are young.

You never come back.

-Carl Sandburg, 1916

About a week after I posted this story, I contacted the editor of the Gaston Gazette, hoping that the newspaper might publish a story about my search for more information. Wade Allen, a reporter, contacted me, and soon an article appeared with the headline, “Man wants to learn more about Gaston child laborer.”

Several weeks later, I received an email from Alta Mitchem Durden, a local historian. The following three paragraphs are excerpts from that email.

“I’ve spoken with Joe Castevens, Landscape and Maintenance Supervisor/City Arborist for Gastonia, regarding ownership of, and burials at, Hollywood Cemetery. According to Mr. Castevens, in 1918 a five-graves burial section was purchased by R. L. Newsom, who was buried in Section R, Lot 163, Western Half, in 1949 at age 71. His wife, Minnie Newsom, was buried in the Hollywood Cemetery in 1927, but the cemetery records do not indicate the precise location; however, it is presumed that her burial is next to or near that of her husband, R. L. Newsom.”

“Mr. Castevens also has records for two other people named Newsom or Newsome who are buried in the same cemetery, but their graves are nowhere near Section R, Lot 163, Western Half. Within the next few days, he will make an inspection of that part of the cemetery in order to try to determine how many of the spaces contain unmarked graves and how many are empty, and will give me a call back with results.”

“It is my thought that perhaps R. L. Newsom bought this cemetery property in 1918 occasioned by the death of his son, Giles Edmund Newsom, in that the wife of R. L. Newsom, Minnie Newsom, died in 1927, or nine years after initial burial space purchase.”

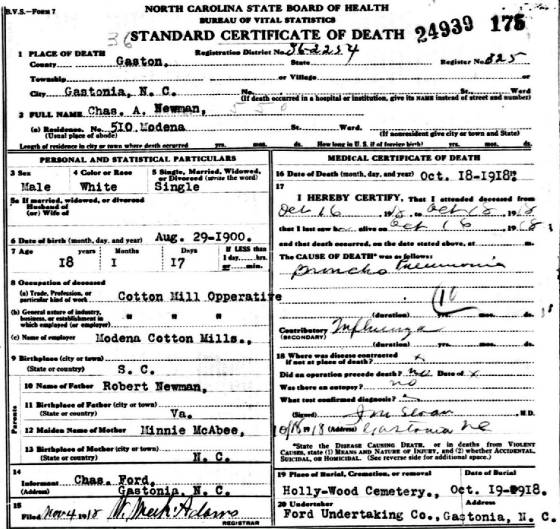

Thus began a chain of events which ultimately led to Giles’s death record in 1918, thanks to the persistence of Ms. Durden, and Brian Brown, Reference Librarian at Gaston-Lincoln Regional Library in Gastonia. Here is what the three of us found.

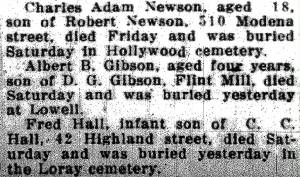

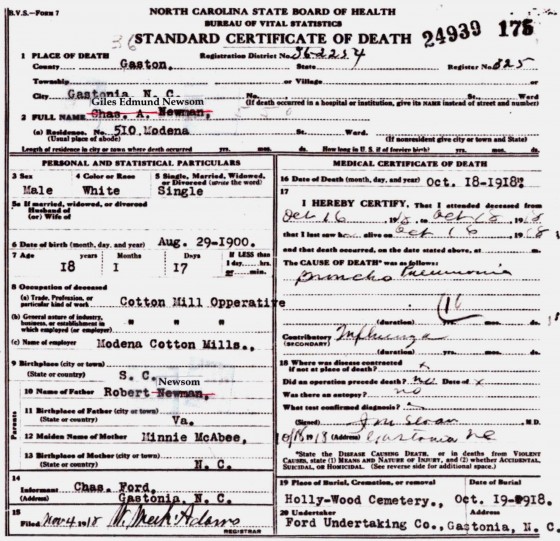

Giles Edmund Newsom died in Gastonia on October 18, 1918. He was one of many victims of the so-called “Spanish Flu” pandemic. I searched the Gastonia death records for October 1918, and 40 of the first 50 people listed died from influenza, most of them between the ages of 1 and 30. According to Mr. Castevens, Giles’s name does not appear in the Hollywood Cemetery records, but it is likely that that he was buried next to his parents in an unmarked grave. At the time of his death, Giles was working at Modena Cotton Mills, despite his missing fingers.

Though I had not been able to find Giles’s death record, Brian Brown did, after noticing a death certificate for Chas. A. Newman, and a subsequent newspaper death announcement Charles Adam Newson. It was obvious that Newman (or Newson) was actually Giles. He was born on August 29, 1900, the same date as Giles listed on his 1918 draft registration. He had the same parents as Giles did. And census records and obituaries for family members clearly confirm that his parents had only three children, Giles and two younger children, Barney and Margerie. And no one named Charles Newman, born about 1900, appears in North Carolina census records in 1900 or 1910.

How could his name have been so badly misspelled on his death certificate? It occurred to Brian, Alta and me that if one says Giles Edmund Newsom quickly and carelessly, it sounds somewhat like Charles Adam Newman. The informant listed on the death certificate was not a family member; it was Chas. Ford, the undertaker. He could have easily misstated the name, or the clerk could have misunderstood the name. Of course, the mistake was repeated in the newspaper death announcement, and then misspelled again (not Newman, but Newson).

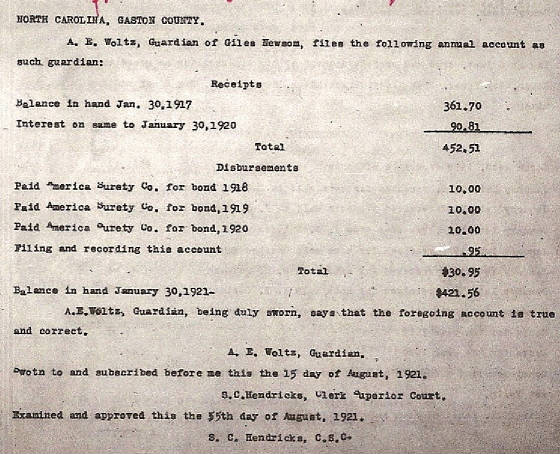

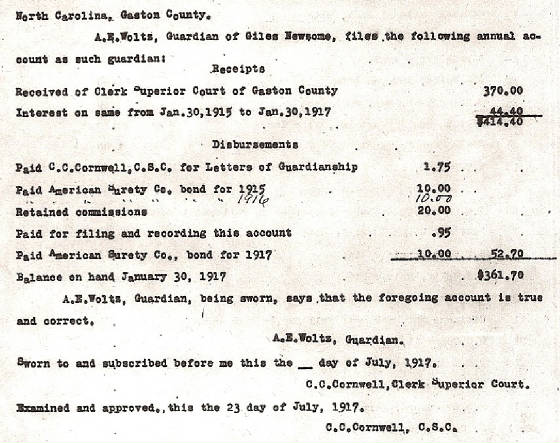

In his photo caption, Lewis Hine stated: “His father (R.L. Newsom) tried to compromise with the Company when he found the boy would receive the money and not the parents.” Ms. Durden decided to explore this issue. Did Giles receive compensation? If so, how much? As a retired legal secretary, she knew where to look. She found probate records indicating that Giles received a settlement of approximately $360.00. As of January 30, 1921, more than two years after Giles’s death, the amount was $421.56, with accumulated interest, but was held by the attorney/guardian of the estate. Despite several inquiries, no records were found to indicate the disposition of the funds.

Poor Giles. He was forced to work under dangerous conditions when he was far too young. He lost two fingers in an accident. Despite that, he returned to work in the textile mills, and was employed in a mill in Gastonia when he succumbed to influenza. He was buried in an unmarked grave. And now we know that his name wasn’t even correct on his death certificate, and he never received any money from the settlement.

I filed an application with North Carolina Vital Records to have his name amended on the death certificate. I explained his circumstances, and provided all the necessary documents to prove that Chas. A. Newman was Giles Edmund Newsom. After waiting more than a month, my application was denied because such an application must be filed by a blood relative. I called and explained that I could not locate any living relatives, and asked why they couldn’t just make the correction, given the overwhelming evidence. But they refused.

So I tried the only option I could think of. I contacted William A. Current Sr., a North Carolina state representative from Gaston County, and asked him to intercede, hoping that his political influence could persuade Vital Records to make an exception. He and Wendy Miller, his legislative assistant, agreed to help, and they kept me posted as they contacted several top officials at Vital Records and the State Registrar’s office. Unfortunately, they received this final reply:

“After acceptance for registration by the State Registrar, no death certificate can be altered or changed except by formal request. The State Registrar is responsible to adopt rules governing these requests and the type and amount of proof required.”

“To begin the process to change a death certificate, your constituent should complete and mail or deliver the request on the form provided (attached) with a $24 search fee (nonrefundable). They will need to note on the form what type of change is needed and why. The request will be evaluated and the registrar will respond in writing as to the approval/denial or if there is more information needed.”

That is precisely what I had already done, but to no avail. So I have submitted a correction to Ancestry.com, where I found the death certificate. And I have (unofficially) corrected the death certificate myself.

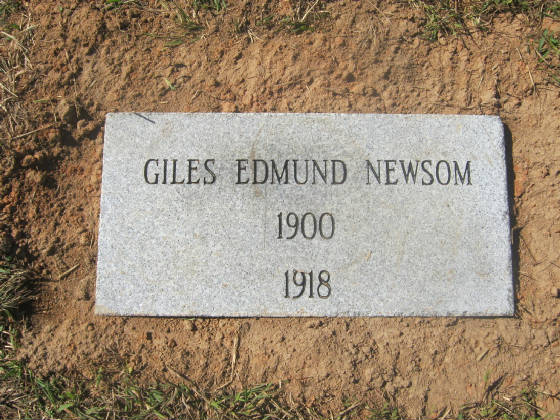

And finally, I decided that it was time for a grave marker to be installed at Giles’s family plot at Hollywood Cemetery, 94 years later. I emailed Alta Mitchem Durden about this, and the next day she replied:

“I’ve just spoken with a friend of mine, Leon Wyant, who owns and operates Wyant & Son Monument Company in Gastonia. Leon had already read the article in the Gazette and noticed my name as a contributor. After I mentioned to him your interest in having a memorial erected for Giles in the Hollywood Cemetery, he asked me to have you give him a call, and that ‘we can probably work something out.'”

And so I called him. He graciously offered to install a flat marker, at no charge, and subsequently made arrangements with cemetery supervisor Joe Castevens. I suggested that the marker should say simply, “Giles Edmund Newsom 1900 1918.”

Rest in peace, Giles.

On behalf of the descendants of Giles Edmund Newsom (whoever and wherever they may be), my heartfelt thanks to Alta Mitchem Durden, Brian Brown, Leon Wyant, Joe Castevens, Wade Allen, Mike Huffstetler, and the late Lewis Hine.

*Story published in 2012.

Steve and Emily (Fairlamb) Parker have added Giles to FindAGrave.com.