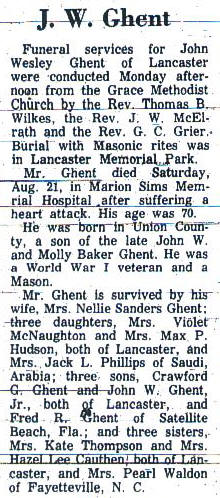

Lewis Hine caption: John Ghent has worked at spinning for 1 year. Goes to school now. Been Sick. Lancaster, S.C. Cotton Mills. Location: Lancaster, South Carolina, November 1908.

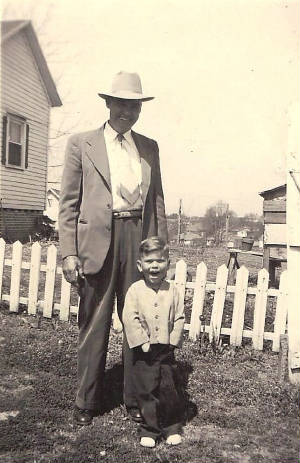

“I thought he was properly dressed. It was probably his only suit.” -Doris Phillips, daughter of John Ghent

COLUMBIA, S.C., Feb 7: The (South Carolina) House of Representatives, by a majority 18 today passed the Marshall bill prohibiting the labor of children under twelve years old in cotton mills. It had passed in the Senate by a large majority.

The bill is to go into effect gradually. Children wholly dependent on their own labor for support, or having widowed mothers are partially exempt. None are to work between 7 P.M. and 7 A.M. Fine and imprisonment is provided for the employment of children under age, and punishment is also provided for parents who make false report of age of their children. –New York Times, February 8, 1903

Representatives of South Carolina cotton manufacturers today appeared before the house labor committee to oppose the Palmer child labor bill. The bill would bar from interstate commerce all goods manufactured by children under 14 years of age, or by children between 14 and 16 years working more than eight hours a day.

Lewis W. Parker said that the South Carolina manufacturers would favor taking the children out of the mills if arrangements could be made to force the children into the schools, and to take care of those dependent upon the labor of children for a livelihood.

Mr. Parker said of 50,000 cotton mill operatives in South Carolina, about 8,000 were children between 12 and 14 years old. No negro children were employed, he said, and he characterized the possible employment of negroes in the mills which, he said the Palmer bill might force, as the “greatest curse that could come upon the south.”

Elizabeth C. Watson, a social and child welfare worker, appeared in favor of the bill and briefly described conditions in the southern mills, declaring that children worked 11 and 12 hours a day at occupations which kept them constantly on their feet. -Herald-Journal, Spartanburg, South Carolina, May 23, 1914

South Carolina’s new child labor law prohibiting the employment of children under 14 years of age in the textile establishments went into effect, and employment of about 2,400 children automatically ceased, according to figures of the state department of agriculture. The old law made the minimum age limit for employment 12 years. –Deseret News (Utah), January 1, 1917

************************

Lewis Hine took over 200 photos of child laborers in South Carolina, in 1908, 1912 and 1913, twenty-three of them in Lancaster, South Carolina, where children worked for Lancaster Mills, owned by Leroy Springs at the time, and later by his son Elliot. The Springs family owned mills all over South Carolina, and much real estate in the Lancaster area.

Hine’s pictures, and the work of his employer, the National Child Labor Committee, played an indispensable role in the slow, but steady eradication of most forms of child labor in the United States. In South Carolina, child labor was especially egregious in the early 1900s, both in textile mills all over the state, and in fish canneries near Charleston.

According to the caption by Hine, John Ghent had been working a year when he was photographed. If that is correct, he would have started when he was 12, as his daughter and grandson attested to in my interviews with them. That would have made him a “legal” worker, according to the state’s law at the time.

I found John Ghent in the census right away. In subsequent records I quickly learned that he had a son and a grandson with the same name. Within a few days after I began my research, I was talking to John Ghent III, also of Lancaster. He already knew about the picture, having found it while searching for family information on the Web.

John Wesley Ghent (the boy in the photograph) was born in Union County, North Carolina on August 21, 1895. He was one of 16 children born to John Ghent and Mollie Baker Ghent. His father was a farmer and carpenter. John married Nellie Rose Sanders in 1921. He was 26 and she was about 17. They had six children. He died in Lancaster on his 70th birthday, August 21, 1965. Nellie died in 1988.

I interviewed his only surviving child, Doris Phillips, and grandson John Wesley Ghent III.

Edited interview with Doris Phillips (DP), daughter of John Ghent. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on May 17, 2013.

JM: You’ve known about the photo of your father for quite some time. What did you think when you first saw it?

DP: I thought he looked like his grandson. He was one of 16 children, and I thought he was properly dressed. It was probably his only suit.

JM: Do you know where he was standing?

DP: Between Tenth Street and the next street going up the avenue. He was in the back yard of the lady who lived on the corner of Brooklyn Avenue and 10th Street.

JM: The 1940 census says he didn’t go farther than the fourth grade.

DP: But he had terrific handwriting.

JM: When were you born?

DP: March 24, 1926. I was the fourth born. I’m the only child left.

JM: What kind of house were you living in then?

DP: We lived in a four-room house. Mr. Springs (the mill owner) owned all of houses where the workers lived. They controlled all the lights, and when it was time to come to work, they flashed the lights. When the weather got too cold in the winter, they would flash the lights to tell us to turn off the water at night to keep the pipes from freezing.

JM: Did he work in the mill all his life?

DP: Yes. The mill was his life. He loved it. He always worked in the spinning room. My mother worked in what they called the quill room, and then she worked in the spinning room.

JM: How many children did your parents have?

DP: Six. The oldest one was Violet. Then Evelyn June, then John Wesley, Jr., then me, then Fred, and then 10 years later, we had Crawford Glen. We called him Glen.

JM: Did you or any of your siblings go to college?

DP: No. Glen and I were the only ones that finished high school. After I graduated, I went to work in Washington, DC, as a secretary for the General Accounting Office. I worked there for a few years, and then I got married and moved to Louisville, Kentucky. Then we moved back to Washington, and then to Cyprus, then to the Philippines and Saudi Arabia. And then we finally came home to Lancaster.

JM: Did most of your siblings stay in the Lancaster area?

DP: Yes.

JM: What was your father like?

DP: He was good man. He was never in debt. He was a man that loved to work. He stayed busy until the sun went down. He also liked to work in his shop and in his garden.

JM: What was your mother like?

DP: She was a very sweet woman. She worked in the mill from six in the morning till two in the afternoon, and still sewed and made clothes for all six of us. And we were all dressed nice. We were all church-going people.

JM: Did your parents ever own a home?

DP: Yes, they eventually bought the mill house they were living in, but after the children had grown.

JM: I see that your father served in World War I.

DP: That’s right. He went overseas. He was gassed in the war. When I was about eight or nine, all the WWI veterans that were gassed or injured were paid a certain amount. I remember Daddy getting a check. He died on his 70th birthday. He had a heart attack. I was in living in Saudi Arabia at the time. I didn’t get the message until the day he was buried.

Edited interview with John Ghent III (JG), grandson of John Ghent. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on April 30, 2013.

JM: What did you think of the photograph of your grandfather?

JG: I think it was pretty cool, since I know all about his history with the textile industry. He said he went to work in the mill when he was 12. There was a weight limit. You had to weigh at least 65 pounds if you were a boy, and I guess he reached that weight when he was 12.

JM: Do you know where he was standing?

JG: It was between Brooklyn Avenue and the old mill. It was in what they call the Brooklyn section of Lancaster, which was on one side of the mill. On the opposite side was a section called Midway. Both consisted of mill houses.

JM: In the 1910 census, your grandfather was living at 34 North Main Street in an area called Cane Creek.

JG: Right. Cane Creek runs through the city, and it was a neighborhood by the creek.

JM: In 1930, he was living at 109 Tenth Street.

JG: That’s correct. He was at the lower end of the mill complex.

JM: In 1940, he was living at 20 Fifteenth Street.

JG: Right.

JM: Did he ever own a home?

JG: Yes. The home that I remember when I was a child was at 1606 16th Street. He lived there till he passed away, and then my grandmother and my Aunt Violet lived there till my grandmother got Alzheimer’s, and they moved into a government subsidized apartment.

JM: Did your grandfather serve in World War I?

JG: Yes. He was a motorcycle courier in Europe.

JM: That was a dangerous job. The enemy could have picked him off easily.

JG: He never talked about it.

JM: Did you live near him?

JG: About two miles away. I saw him on a weekly basis.

JM: What was he like?

JG: He was very well liked. Everyone in the neighborhood really thought a lot of him. When I was about seven or eight, he got colon cancer. They did a colostomy. He had to carry a bag, and because of that, he didn’t go to church. So when my grandmother went to church, he would pick me up. He had some friends that owned a grocery store, which was a local hangout for elderly gentlemen. For me, it was kind of like having a history lesson.

JM: What did he like to do when he wasn’t working?

JG: He had a woodworking shop, detached from his home, and he did a lot of woodworking projects. He would help out neighbors if they needed something, like making them a cabinet.

JM: Did he ever show you how to do anything in the shop?

JG: Yes, he did. I would help him out. I was impressed with his organizational skills, as far as separating bolts and nails and screws. He had them all in little jars.

He lived at the end of the street, right near a bunch of stores. He had a reddish colored cocker spaniel. His name was Wiggles. Every afternoon, at the same time, Wiggles would walk up to the drugstore, and the owner would put a little cardboard container of vanilla ice cream in a small paper bag, fold the top over, put it in Wiggles’ mouth, and he would go back to my grandfather’s house, and my grandfather would open the container and give Wiggles the ice cream.

JM: What was your grandmother like?

JG: She was the typical housewife. She worked off and on at the mill, but not a lot. When you went to her house, she always had a cake. The dining room table seated 16 people, so there were always a lot of family meals there, especially on the holidays.

JM: Your father, John Wesley Ghent Jr., passed away in 2007. What did he do for a living?

JG: He was a machinist for the Springs Foundry and Machine Shop.

JM: Did he go to college?

JG: No, but he took some technical courses under the GI Bill when he got back from World War II. None of my grandparents’ children went to college. I didn’t go to college either; I joined the Air Force. When I got out, I worked about seven years as a welder, and then they moved me into management. I progressed up to a department manager. For the last four years, I was in sales.

JM: Does your family still talk a lot about your grandfather?

JG: No. Most of my cousins live away from here. I’ve talked about that a few times with people lately. Sunday used to be family day. You went to visit aunts, uncles, cousins and grandparents. But in this age, everyone is traveling, and we have the social media, so the traditions have faded away.

JM: Lewis Hine took your grandfather’s picture because he wanted to expose child labor, which was common then in the mills owned by Mr. Springs.

JG: I never heard any of the old employees at the Springs Mills complain about the working conditions, the hours, or the pay. I think everyone appreciated having a job. During the Depression, because the company was so strong, and because Colonel (Elliot) Springs, the owner, was such a caring person, nobody lost any work time. I remember sometimes that someone would say something derogatory to my grandfather about working in the mills, and he was always quick to mention that. I think that was one of the reasons why people were so loyal to the mills, even though they did exploit children.

“This picture was taken about 1952 at their house at 1606 16th Street. The house is to the left, and the structure in the background was a chicken coop. The thin vertical strip of white on the right was the door of his woodworking shop. All of the houses in the background were mill houses, and beyond that was Springs Mills.” -John Wesley Ghent III

*Story published in 2013.