This little girl, identified by Lewis Hine simply as “spinner,” has been staring out the window for 105 years, waiting for someone to give her a name. The waiting is over. Her name is Lalar Blanton.

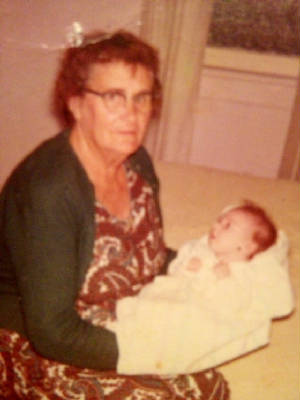

“Granny was my security, my safe place to fall. She was the softness and the love in my life.” -Myra Cook, granddaughter of Lalar Blanton

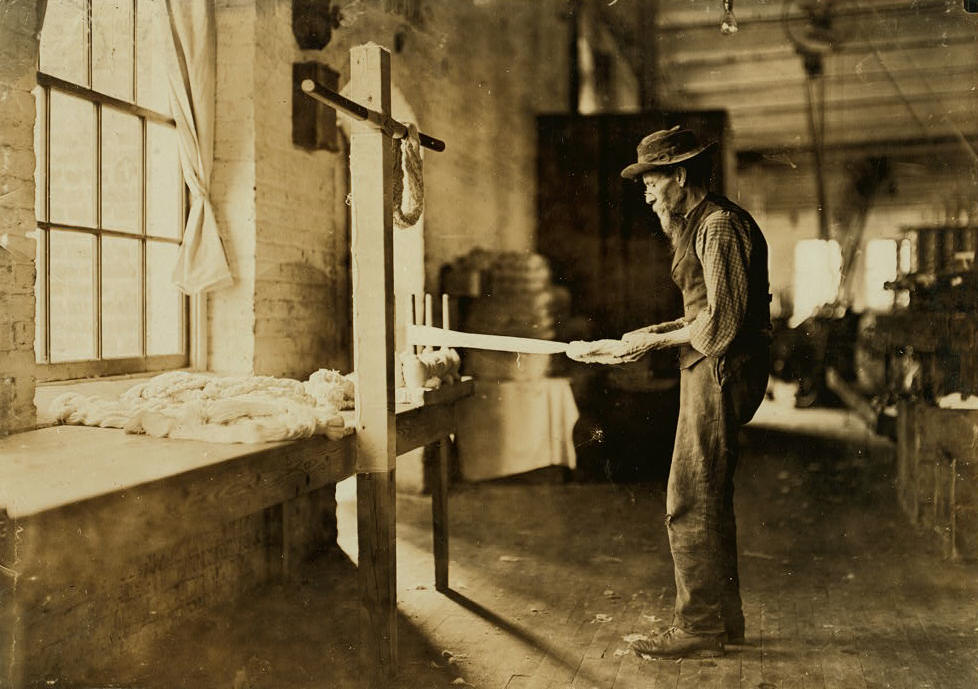

Lewis Hine spent the whole month of November 1908, photographing children working in textile mills in North Carolina and South Carolina. He had begun traveling extensively for the National Child Labor Committee in August, first in the Midwest, and then in the South. With only three months of investigative work behind him, he was not well known among mill owners, so he generally had little trouble getting inside the mills. He usually posed as an industrial photographer looking to take pictures of machines and other equipment. He took only two pictures of child laborers in the Rhodes mill. This is the other one.

It appeared obvious to me right away that the girl on the left was also the girl looking out of the window, and that the two persons with her were her mother and sister.

The girl looking out of the window has become one Hine’s most beloved and talked about images. For his work, he used a large camera, with a wide-angle lens and a very slow shutter speed. He had to mount it on a tripod. Consequently, he usually posed his subjects, and tried to get them to hold still, not an easy task for a child. For the flash, he had to ignite magnesium powder, not a good idea in a lint-filled cotton mill; so he had to find a spot with adequate light. Hine would have understood that having the girl facing the light-filled window was ideal.

But most people think that there was another reason. The caption said, “A moment’s glimpse of the outer world.” It is easy to conclude that Hine was tugging at our hearts by placing the girl in that location to create a romantic image of a poor mill worker dreaming of a better life somewhere out there, or just wishing she were home. But all of Hine’s captions were field notes he jotted down in a pocket notebook, and some were later edited and/or added to by the National Child Labor Committee. Hine often complained about that. So we don’t know for sure what Hine intended, but we do know that he created a picture that is unforgettable.

But for some reason, Hine did not record her name. Perhaps the family was reluctant to reveal their names to a stranger.

Almost five years ago (2009), I began a search for the girl’s identity. I asked the editor of the Lincoln Times-News, the newspaper that covers Lincolnton, to publish the photos and ask if anyone knew who she was. I had already used this method successfully for several other Hine pictures. The editor agreed to do it. The article said in part:

“The little girl staring out the window has no name and a very short story. At 10 years old, she had been working at Rhodes Manufacturing Company for more than a year. ‘She has been anonymous for 101 years,’ says Joe Manning, an author and historian. ‘Whoever she was, someone remembers her and probably loved her and cared about her.'”

No one responded. So I posted the pictures on the Mystery Photos page of my website. Three years went by, and nothing happened. About six months ago, I saw a painting inspired by the photograph. It was by Dawn Nelson, who contributed a number of art works to a traveling exhibit called “The Mill Children.” The exhibit has its origins in North Adams, Massachusetts, and is inspired by Hine’s nine photographs of child laborers in the city at the Eclipse Mill, as well as others taken by Hine. I contributed stories of some of the children, and an educator and several other artists made contributions. When I saw Ms. Nelson’s painting of the girl looking out the window, I decided to make another effort to identify her.

A couple of days later, I came up with a novel idea. I searched the 1910 Lincolnton census, and made a list of all the white girls who were born about 1898, and had a sister that was about two years older. There were 12 such girls, including one identified as Lala Blanton. I published those 12 names under the photos on my Mystery Photos page.

It occurred to me that there are thousands of people searching every day for information about their ancestors. What if the girl at the window was really one of those 12 persons, and what if someone was searching that name on Google and found the photos on my website? It was a long shot at best, but what other option did I have at that point?

Two months later, I received an email from a woman named Myra Cook.

“I think there is a real possibility that the little mystery girl in the photograph is my grandmother, Lalar Blanton. And in the other photograph, the mom and the two sisters are my great-grandmother, Susie Black Blanton, with Lalar on the left, and Ellen on the right. Susie looks very much like my father, who was her grandson. I’m not sure how to determine if I am correct, but perhaps you have some idea how to do that.”

I quickly replied.

“This is very exciting, so let’s work on seeing if we can establish if you are correct. The 1910 census lists Susan, Ellen and Lala (instead of Lalar) in Lincolnton. Lala is about 10 years old, and Ellen about 12 years old. Do you have any photos of Lalar, Ellen and Susan?”

A week later, she sent me several pictures of Lalar as an adult. I compared them to the girl in the Hine photos, and concluded that they were the same person. I showed them to three friends I hang out with at a local coffee shop, making sure I did not give them any hints ahead of time about what I thought. Not only did they come to the same conclusion, but several curious coffee drinkers from another table came over to see the pictures, and they agreed.

At that point, I emailed the photos to Maureen Taylor, a widely known face recognition expert whose expertise I have relied on in the past. She replied: “The faces match up perfectly!”

At the end of this story, I will illustrate how we came to this conclusion.

Lewis Hine caption: Rhodes Mfg. Company, Lincolnton, N.C. Old man inspecting yarn. Been in cotton mills over 20 years. Location: Lincolnton, North Carolina, November 1908

“The current was turned on in the Rhodes Manufacturing Co. last week. The new mill is run by Southern Power company. The mill has 5,000 spindles and 150 looms, is modern in architecture, and has the best machinery equipment. Mr. John M. Rhodes is manager. This is the first mill to be started at Lincolnton with electricity.” –Spartanburg Weekly Herald (South Carolina), November 14, 1907

The following are excerpts from Twenty-Second Annual Report of North Carolina Department of Labor, compiled in 1908.

LAW RELATING TO CHILD LABOR

The General Assembly of North Carolina do enact:

Section 1: That no child under twelve years of age shall be employed or work in any factory or manufacturing establishment within this State. Provided further, that after one thousand nine hundred and seven (1907), no child between the age of twelve and thirteen years of age shall be employed or work in a factory except in apprenticeship capacity, and only then after having attended school four months in the preceding twelve months.

Section 2: That not exceeding sixty-six hours shall constitute a week’s work in all factories and manufacturing establishments of this State. No person under eighteen years of age shall be required to work in such factories or establishments a longer period than sixty-six hours in one week: Provided, that this section shall not apply to engineers, firemen, machinists, superintendents, overseers, section and yard hands, office men, watchmen or repairers of breakdowns.

Section 3: All parents, or persons standing in relation of parent, upon hiring their children to any factory or manufacturing establishment, shall furnish such establishment a written statement of the age of such child or children, being so hired, and certificate as to school attendance; and any parent, or person standing in the relation of parent to such child or children, who shall in such written statement misstate the age of such child or children being so employed, or their school attendance, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction shall be punished at the discretion of the court. Any mill owner, superintendent or manufacturing establishment who shall knowingly or willfully violate the provisions of this act shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction shall be punished at the discretion of the court.

Section 4: After one thousand nine hundred and seven (1907), no boy or girl under fourteen years old shall work in a factory between the hours of 8 P. M. and 5 A. M.

Section 5: This act shall be in force from and after January first, one thousand nine hundred and eight (1908).

In the General Assembly, read three times, and ratified this the 9th day of March, A. D. 1907.

**************************

“In regard to the child-labor law, I think the law we have is very good and should be enforced. Since the children are out of the mills, we think it would be better to have them in school and keep them off the streets and out of danger of learning the vices so common in the towns.” -J. M. Rhodes, President Rhodes Manufacturing Company, Lincolnton, published in the Annual Report of the North Carolina Department of Labor and Printing, 1908

According to Lincoln County Revisited, by Jason L. Harpe: “Rhodes was also responsible for the 22 mill houses that served the workers who made their living at the mill. E.O. Anderson, Thorne Clark and David Clark purchased the mill from Rhodes after World War I, renamed it Anderson Mill, Inc., and operated it until 1929. The group renamed the mill Massapoag and wove cotton duck to line shoes. Long Shoals Cotton Mill operated Massapoag from 1957 to 1971.”

John M. Rhodes died in 1921. Ironically, the mill he built burned down this year, on June 17, 2013, two months before Lalar Blanton’s granddaughter contacted me.

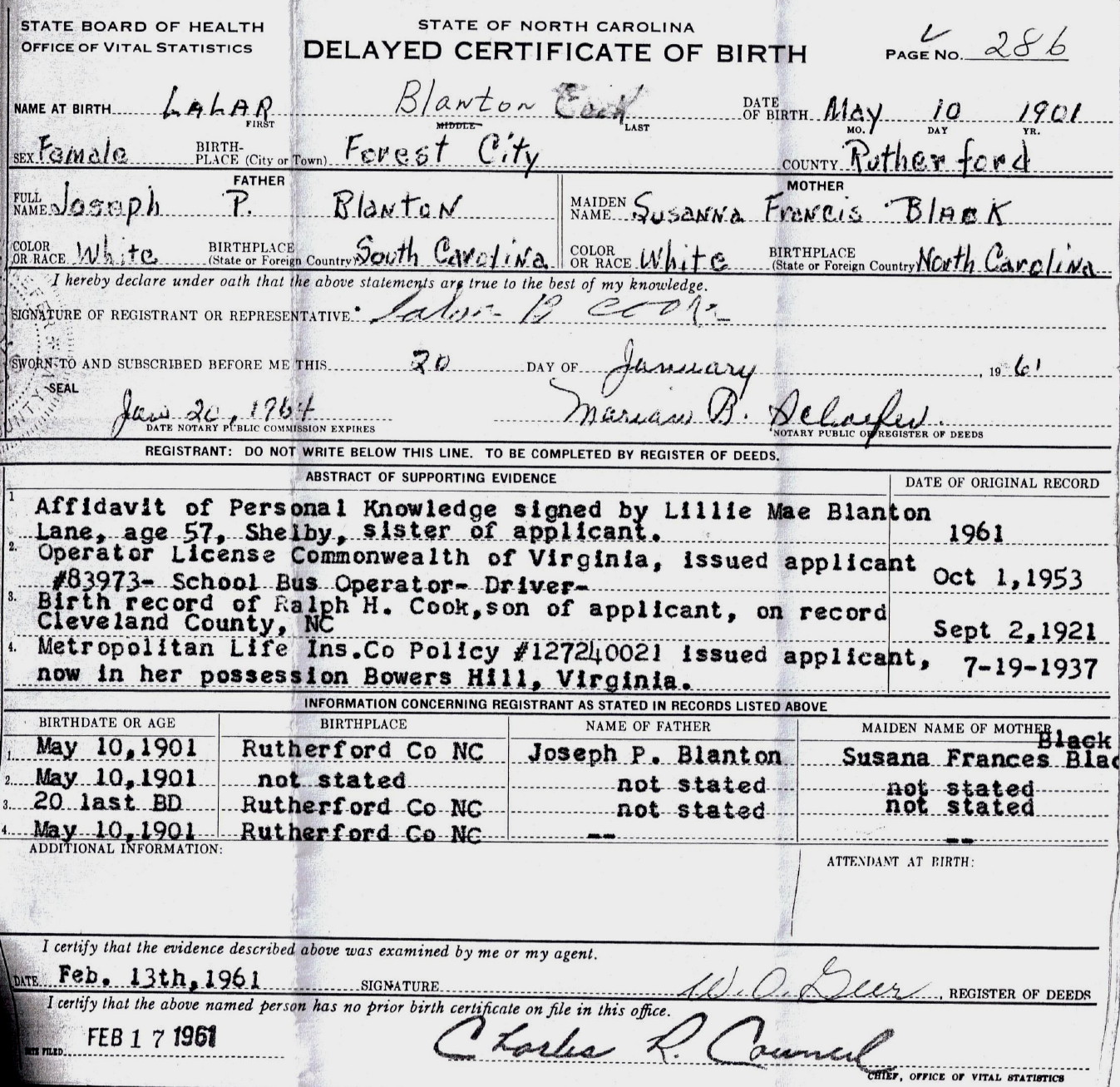

Lalar Blanton was the second of four children born to Joseph P. Blanton and Susanna (called Susie) Frances Black, South Carolina and North Carolina natives respectively, who were married in about 1894. According to the North Carolina Birth Index, Lalar was born in Forest City, an unincorporated town in Rutherford County, North Carolina, on May 10, 1901. But the year is unlikely. If correct, Lalar would have been only seven years old when she was photographed by Lewis Hine. Looking at the pictures, that is hard to believe. She looks to be at least nine or ten. Hine said she was 10, probably because her mother told him so.

How old was she?

I obtained a copy of her birth certificate, but it turned out to be a “delayed birth certificate,” meaning that it was applied for a substantial time after the birth. Births were not officially recorded in North Carolina before 1913, so anyone wishing to obtain an official birth certificate for a person who was born before 1913 must apply for a delayed certificate, and provide reasonable proof of date of birth.

Lalar applied for her delayed birth certificate on January 20, 1961, six decades after she was born. As proof, she provided four items of “reasonable proof”: Affidavit of Personal Knowledge from a younger sister; driver’s license issued in Virginia in 1953, birth record of Ralph Cook, her son, issued in 1921 (on which her date of birth is listed); and life insurance policy issued in 1937. Although the State of North Carolina accepted this information, all of the items would have been obtained without official proof of her date of birth, since such proof did not exist. So the delayed birth certificate does not prove that she was born in 1901.

In the 1910 census, she was listed as 12 years old, living in Lincolnton, and working in a cotton mill. Lalar’s mother probably gave the age to the census taker. The census was taken on May 4. Lalar’s birthday was listed as May 10 on all of her important records, so it seems likely that May 10 is correct. What is debatable is whether the year was 1901.

If the 1910 census was correct, she would have been born in 1897, and would have become 13 years old, six days later. But since her birthday was only six days away, her age might have been given as 12, when she was technically still 11 years old. If that was the case, then she would have been born in 1898. Unfortunately, her family did not appear in the 1900 census, so we can’t use that as further evidence. In subsequent censuses, Lalar gave her birth year as 1901, which is consistent with what she claimed on her delayed birth certificate, the supporting documents, and her delayed marriage certificate, also issued in 1961. But that didn’t mean that she was correct. In those days, many people did not know for sure when they were born.

In my opinion, she was probably born in 1898, which would have made her 10 years old when she was photographed. But whatever is correct, she clearly worked at the mill illegally, according to the 1907 North Carolina law, especially since she stated that she had already been working in the mill for a year when Hine photographed her.

Lalar married Clemmie Zeno Cook on August 31, 1919, in Cleveland County, North Carolina. Known as Clem, he was a painter. They had two children. They lived in Washington, DC, for several years; and then lived a long time in the Portsmouth/Norfolk area of Virginia, before finally settling in Shelby, North Carolina. Clem died on October 22, 1971, at the age of 72. Lalar died on September 22, 1973, at the probable age of 75.

Lalar’s mother Susie, pictured with her at the mill, died in 1961, at the age of 91. Lalar’s father Joseph died in 1927.

Lalar’s sister Ellen, also pictured at the mill, was born Barbara Ellen Blanton, in 1897. According to the 1930 census, she was living in Shelby, with her husband, June Moss, in a rented house right next to sister Lalar. They married in 1913. Ellen was a spinner in a cotton mill, and husband June was doing “odd jobs.” In 1940, still childless, Ellen and June were living with Ellen’s mother Susie. Both Ellen and her husband were working in a cotton mill. A year later, on August 3, 1941, Ellen died of a heart condition. She was only 44. I could find no further information about her.

Edited interview with Myra Cook (MC), granddaughter of Lalar Blanton. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on October 3, 2013.

JM: How did you find the picture on my website, and why did you think the girl was your grandmother?

MC: I was doing some research on my family history. My grandmother’s first name was Lalar, but when I typed Lalar Blanton in Google, nothing came up. I thought about all the different accents in the country and how that could affect the way someone might spell Lalar if they heard it spoken. So I tried Lala Blanton, and I found the two pictures on your website, and a list of 12 girls that you thought could possibly be the girl. One of them on the list was Lala Blanton. I had seen the picture once before online, and I remembered the stories my grandmother told about being seven years old and having to pick cotton, but I didn’t recall her talking about working in the mills. When I saw the pictures, I noticed a family resemblance, and I began to get excited about the possibility that she might really be my grandmother. So I contacted you.

JM: After you sent me some pictures of her, I was able, with the help of a face recognition expert, to confirm that the girl was your grandmother. When I told you that, how did you feel?

MC: I was amazed, but it made me feel sad for her, because she had to work so hard. She never had a chance to be a girl. I’ve always appreciated how good she was to me. She was so fiercely protective of me and wanted me to have a childhood. I am thinking that she might have felt that way because of what she went through.

JM: What year were you born?

MC: 1963. I lived with my grandmother from the time I was four-and-a-half years old, until I was about nine. She died when I was 10.

JM: Why did you live with her?

MC: My parents had a lot of problems that I would rather not talk about, and they just couldn’t take care of me at that time. Granny was my security, my safe place to fall. She was the softness and the love in my life.

JM: What happened when she died? Who took care of you then?

MC: I went back and lived with my parents, until I was 12. Then they got divorced, and my mother and I moved to Indiana. Suddenly, I didn’t live anywhere near my family, my aunts and uncles and cousins, or my childhood friends. It was hard.

MC: She and my grandfather Clem had two sons, Howard, and my father Ralph. Both of them were born at home. At some point, my grandparents moved to Bowers Hill, Virginia, which is near Portsmouth. They also lived in Deep Creek, also near Portsmouth. My grandfather was a painter at the Naval Shipyard in Portsmouth. At some point, they lived in Washington, DC, where my grandfather worked at the Naval Shipyard there, and also painted houses. In his later years, after he retired, he continued to paint houses. When they lived in Washington, my grandmother ran a boarding house. My grandfather had two brothers that also worked in the shipyard, and they lived with their families in the boarding house. I think my grandmother also drove a bus at some point. She was a big woman when I knew her. She was about 5′ 10″, and weighed about 200 pounds. It’s funny. When you look at the picture of her looking out the mill window, you would never think she would grow up to be so tall. She was probably a tall child, too.

JM: When did they leave the Portsmouth area?

MC: They left in the 1960s, and went back to North Carolina. My grandfather had a stroke when I was five, but up until that time, he was painting houses. When he was in Washington, DC, he painted Kate Smith’s house. He was so proud of that. (Smith was a singer remembered especially for her recording of ‘God Bless America.’)

JM: According to the 1930 census, your grandparents were living in Shelby, North Carolina.

MC: Yes. My dad and his brother were still little boys then.

JM: Your grandmother’s delayed marriage certificate shows that she was married on August 31, 1919, when she was 18, according to her delayed birth certificate, although she gave her age as 19 on the marriage certificate. They were listed in the Washington directories from 1933 to 1936. In 1938, they were listed in the Norfolk (Va.) directory. In 1940, they were living in the Deep Creek section of Norfolk, and in 1944, they were living in the Bowers Hill section of Portsmouth. In the 1940 census, your grandmother was asked how far she got in school, and she said it was the fourth grade. And your grandfather said he had finished the seventh grade.

MC: I don’t think the school information was correct. I always heard that my grandmother went to school until the second grade, but that doesn’t mean she finished the second grade. And as far as I know, my grandfather only got as far as the fourth grade.

JM: Her death certificate says she died of a heart attack in Cleveland Memorial Hospital in Shelby.

MC: I think she actually died on the front porch.

JM: Had she been ill for a while?

MC: No. It was sudden.

JM: Where were you when she died?

MC: I was at school. My mom came to get me and told me there was something wrong with Granny. We went to the house. She went in while I stayed in the car. Then she came back, and as she was backing the car out of the driveway, she told me that Granny died. I remember that I was hysterical.

My grandfather had died when I was seven. I was at school when it happened, and nobody came to tell me. There were three girls who lived next door who went to school with me, and when school ended every day, there was a taxi that took us home. At that time it was a custom in the South that when somebody died, there would be a wreath on the door of their house, and the funeral home would put up signs in the immediate neighborhood. So when the taxi got near the house, we saw the signs and wondered who had died. Then we got to my house, and the wreath was on my door and I knew that my grandfather had died. So I guess that is why my mom fetched me from school when Granny died, so I wouldn’t experience that trauma again.

JM: What did your grandmother tell you about her childhood?

MC: Sometimes when we were riding in the car and we would pass a cotton field, she would talk about how she had to pick cotton, and how it made her back hurt. I remember that I wanted to go pick cotton because I wanted to see what it was like. Several years ago, I was driving my daughter home from college, and we were talking about cotton fields, and we actually stopped by a cotton field so we could pick some. But it was raining, and my daughter didn’t want to get wet, so I ran out quickly and picked a little bit of cotton and gave it to her. I think she still has it.

JM: When you knew your grandmother, was she fairly well off, or was she poor?

MC: She lived in a nice house, with a nice bathroom, a modern washing machine and an air conditioner. Everything was neat as a pin and spotless. It was the quintessential mid-century modern American home. After my grandfather died, she bought herself a Baldwin piano. She had never taken lessons, but she could play by ear. She did not trust banks, so she kept her money at home. She kept all her cash in a Cool Whip container in the freezer. When she died, they found $15,000 in the container. My grandparents had saved their money. My grandfather had a pension, and my grandmother had Social Security. Like most people during the Depression years, they were very thrifty, and paid for everything in cash.

JM: Did either of your grandmother’s children go to college?

MC: No. My father Ralph served in the Marines in World War II. He was with the first wave of soldiers at Iwo Jima. He also served in Korea. After the World War II, he worked as a policeman in Colonial Heights, Virginia. So did his brother Howard. In his later years, my father worked as a cook, and when he died in 1987 from heart disease, he owned and operated the Rocky River restaurant in Chimney Rock, North Carolina. Howard worked at the Exxon facility in Norfolk, Virginia, and was president of the Joint Counsel of Oil Workers Union for the USA. I don’t know what his specific job was. He died in 1999 from ALS (often called Lou Gehrig’s disease).

JM: What did you do with your grandmother that was special?

MC: We played school, and I would be the teacher. I would read to her. I helped her make biscuits, which she made from scratch every single morning. She would use an old peanut can to cut the dough. She would make little shapes, just for me, from the leftover dough that was in between. She called them terrapins.

JM: Do you make biscuits?

MC: Absolutely. I learned from her, and I am proud of it. I still have the peanut can she used.

By Dawn Nelson (DawnNelson.org), inspired by Lewis Hine photograph of Lalar Blanton. Used with the artist’s permission.

**************************

On March 22, 2014, four months after I completed this story, I received the following email from Jennifer Janisch, Lalar’s great-granddaughter. She and her mother Myra Cook (Lalar’s granddaughter interviewed in this story) visited the former Rhodes Manufacturing Company mill, where Lalar had been photographed in 1908 by Lewis Hine.

“My mother and I visited the mill where my great-grandmother worked as a child, along with her mother Susie and her sister Ellen. When we drove up, fire trucks and firefighters lined the street. They had just put out the third fire that had sprung up in the mill since it caught fire last summer. They told us we were lucky to have come upon it now, as it is scheduled to be razed to the ground next week. We took a couple of bricks and a couple wheels that previously had been attached to the bottom of the mill’s doors (or perhaps were attached to the bottom of cotton looms or some sort of cart).”

“The roof was caving in, and it was clear the space had been used over the years by homeless people. I took one step inside, and suddenly felt something physically push me back out of the mill. It was the strangest feeling I’ve ever experienced, and I felt a sense of fright. Mom and I think it was Granny telling us: ‘Get out of there; y’all have no business being in there. It’s dangerous and dirty.’ No doubt she had very rough memories of the place and wouldn’t want us anywhere near it.”

How did Maureen Taylor and I conclude that the unidentified girl in the Lewis Hine photos was Lalar Blanton?

*Story Published in 2013.